15

Cross-cultural perspectives

Dr. Alicia Walker

The mosaic depicting the sixth-century empress Theodora and her retinue in the church of San Vitale (Ravenna, Italy) shows the empress’ attendants dressed in multicolored, luminous garments with repeating patterns indicative of woven silk.

Although rendered in mosaic, a medium in which Byzantine craftsmen held unrivaled expertise, the image depicts Byzantine courtiers as consumers of an intercultural market of luxury goods. (Intercultural refers to something occurring between or involving contact across two or more cultural groups, usually across geographic and/or political divides.)

At the time this mosaic was executed, the empire had not yet mastered sericulture (the cultivation of silkworms), which required special conditions to raise mulberry bushes, the sole source of food for the silk moth (bombyx mori). Both the raw material of silk and the cloth woven from it were imported at great expense from points east, especially China, which held a virtual monopoly in silk cultivation and processing. Women of the court were among the few members of Early Byzantine society who could afford this lavish material, which demonstrated not only wealth but also privileged access to circuits of trade. Similarities among Sasanian, Early Byzantine, and early Islamic textiles indicate that silk weavings across these cultures shared not only material characteristics but also iconographic, stylistic, and technical features. The interconnectedness of Byzantium with other societies through trade, diplomacy, and military conflict had direct bearing on the development of Byzantine art and architecture, and Byzantium also impacted the formation of other late antique and medieval artistic traditions.

In the early fourth century, when Constantine I was named emperor, the Roman-Byzantine Empire extended throughout Afro-Eurasia (the landmasses and interconnected societies of Africa, Europe, and Asia), from Britain in the northwest to Syria in the East and across the coast of North Africa in the south.

The Roman-Byzantine Empire participated in extensive trade and diplomatic contacts with a wide range of societies, such that the period has been characterized as one of “incipient globalization.” [1] In the fourth to fifth centuries, Northern Eurasian migratory groups vanquished the western provinces of the Roman Empire, even sacking Rome itself. Early modern European historians overinterpreted the late antique and medieval eras as a “Dark Ages,” focusing on breakdowns in long distance communication and supposed declines in cultural achievement in Western Europe while ignoring the vital, cosmopolitan cultures of the eastern Mediter- ranean and Near East.

During this period, the eastern Roman-Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople, weathered centuries of periodic geo-political instability, socio-religious change, and economic crisis, all the while maintaining and further developing commercial and diplomatic contacts across late antique and early medieval Afro-Eurasia. A sense of the convergence of military might, cultural identity, and exotic goods is conveyed by the so-called Barberini Ivory.

The triumphant emperor on horseback at center receives blessings from Christ, above, and a gesture of subservience from Ge (the personification of Earth) below. Yet the image also asserts the emperor’s dominion through the depiction of conquered peoples. A cowering figure behind and to the left wears the quintessential costume associated with depictions of late antique “Persians” (that is, Sasanians): leggings, a knee-length tunic, and a pointed cap. He touches the emperor’s standard submissively.

Below, foreign peoples (Persians, Indians) in their distinctive dress bear tribute for the emperor, including a diadem (a headband, often adorned with jewels and sometimes serving as an indication of rulership), exotic animals, and an elephant tusk. The latter detail inflects the viewer’s appreciation of the polyptych itself, which is fabricated from ivory that was likely traded via Aksum, a Christian kingdom (located at the intersection of modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Yemen) that was a major actor in trade between the Mediterranean, Africa, and India. In the Early Byzantine era, ivory was sourced from India and Africa, where elephants were indigenous. The Barberini polyptych, therefore, embodies in its very materiality the ideals of universal might and intercultural control of precious resources conveyed in its iconography.

<img class="wp-image-59561" style="border: 0px;max-width: 100%;height: auto;vertical-align: middle;margin-right: auto;text-align: center;margin-top: 8px" src="https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Barberini-cowering-figure-30016220236_724bc9d3e3_o-870×1150.jpg" alt="Detail of figure in Persian garb, Barberini Ivory, Constantinople (?), 525–550, ivory, ca. 34 x 19 x 3 cm (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)” width=”254″ height=”336″ aria-describedby=”caption-attachment-59561″> Detail of figure in Persian garb, Barberini Ivory, Constantinople (?), 525–550, ivory, ca. 34 x 19 x 3 cm (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) <https://flic.kr/p/MJqYwy>

Silk textiles, like those worn by Theodora’s attendants in the mosaic at San Vitale, were among the foreign goods most coveted by the Early Byzantine elite. (See image below.)

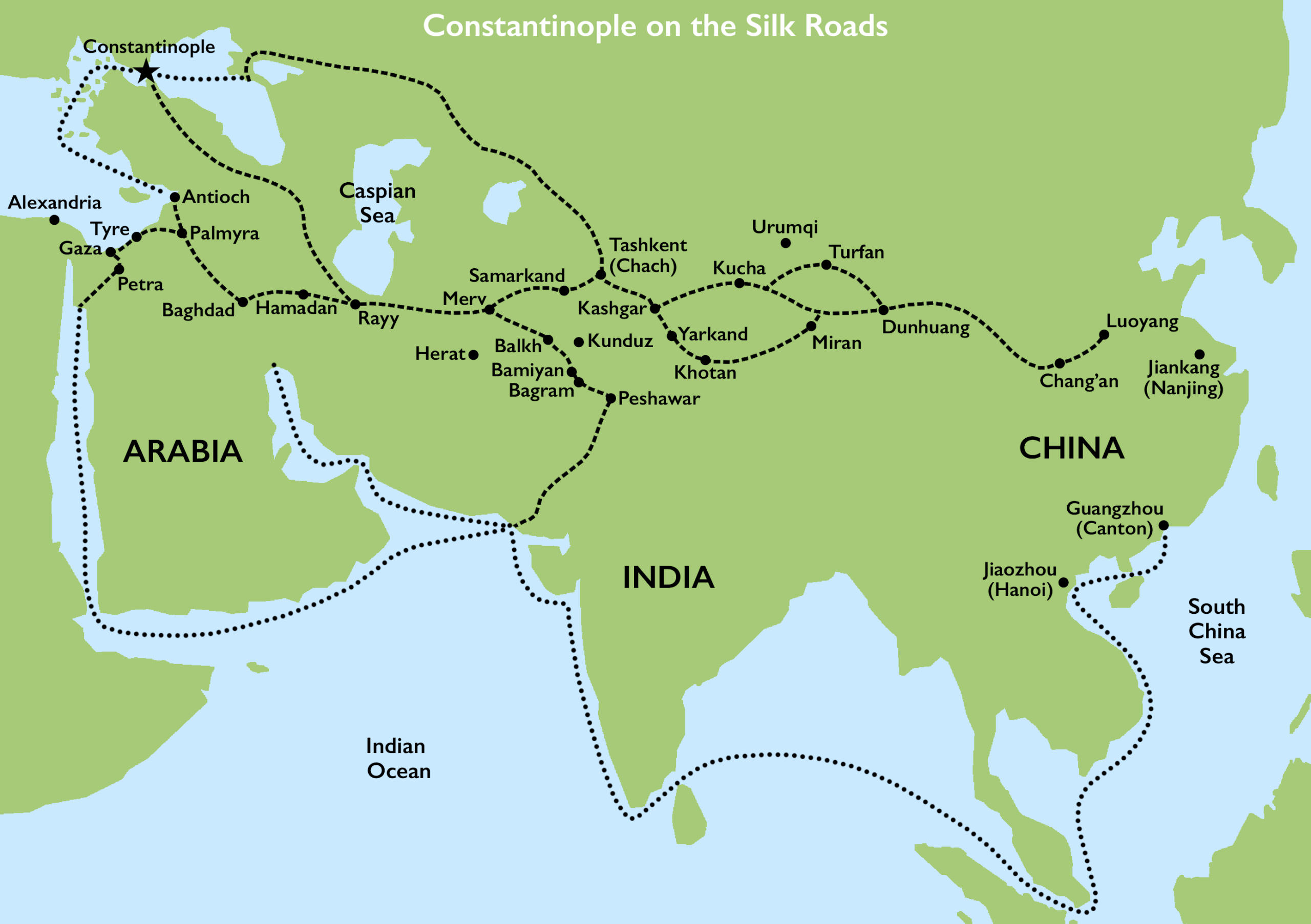

Desire for silk, spices, precious stones, and other luxury commodities anchored Constantinople as the western terminus of the so-called Silk Roads. (The Silk Road was a network of land and sea routes that ran from East Asia to the Mediterranean world, and dominated the trade of luxury items, such as silk textiles, jewelries, and gold and silver vessels.)

<img class="wp-image-59505" style="border: 0px;max-width: 100%;height: 320px;vertical-align: middle;margin-right: auto;text-align: center;margin-top: 8px" src="https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Theodora-detail-870×870.jpg" alt="Detail of the wall mosaic depicting the attendants of empress Theodora’s wearing luxury silk garments of diverse designs, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)” width=”320″ height=”602″ aria-describedby=”caption-attachment-59505″> Detail of the wall mosaic depicting the attendants of empress Theodora’s wearing luxury silk garments, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) <https://flic.kr/p/2m67UL3>

Objects and raw materials—as well as artistic ideas and forms—traveled back and forth along these routes by land and sea from Europe and Africa to the eastern edges of Asia. Early Byzantine silks, glass, and coins have been discovered in graves and treasuries from Britain to China—and even in Japan. Sixth- or seventh-century Byzantine silver vessels with control stamps (a mark guaranteeing the metal content of an object and, thereby, its monetary value) discovered in the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at the site of Sutton Hoo (Suffolk, England) bespeak the westward circulation of Byzantine objects in this period. Rosette motifs (schematic flowers) on these bowls may have been interpreted by Anglo-Saxon viewers as a sacred tree motif, thereby bridging Christian and pagan Anglo-Saxon iconographic traditions. [2]

Early Byzantine efforts to secure the borders of the Empire sometimes involved alliances with foreign peoples. For example, the Arab-Christian kingdom of the Ghassanids was a client state of the Early Byzantine Empire. (The Ghassanids converted to Christianity in the early Christian period and became vassals of the Roman state; they lived at the eastern edge of the Roman-Byzantine Empire and acted as a buffer against the eastern enemies of Rome and as allies fighting on behalf of Byzantines against the Sasanians.)

In the sixth and seventh centuries, they assisted in defending the Roman-Byzantine Empire against Sasanian and Muslim adversaries. Similarly, the nomadic Avars, who originated in the Eurasian Steppe, were allies of the Early Byzantine Empire. They received substantial gifts in the form of Byzantine coins and precious objects (and engaged in raids to obtain additional booty). The Avars were skilled metalworkers and also produced their own works of art in imitation of Byzantine models.

The so-called Ewer of Zenobius is a silver vessel inscribed in Greek around its neck. It may have been fabricated in a Byzantine workshop and then gifted to an Avar leader or it may have been produced (or altered) by Avar craftsmen who emulated Byzantine artistic techniques, control stamps, and/or inscriptions. (See image below.)

As the Byzantines lost their eastern territories to encroaching Islamic armies in the seventh century, the Muslim political and military elite inherited Roman-Byzantine visual and material culture in the lands they conquered. This is especially apparent in the desert villas constructed in regions settled by the first Islamic dynasty, the Umayyads. The extensive wall painting program in an early eighth-century bath house at the Umayyad residence of Qusayr ‘Amra (in modern Jordan) employed a rich array of Roman-Byzantine iconography, including astronomical imagery, portraits of Byzantine and other early medieval rulers, hunting scenes, and depictions of bathers.

The famed early Islamic shrine known as the Dome of the Rock was modeled after Early Byzantine commemorative structures and is decorated in an elaborate program of mosaics and marble revetment that in part emulates Byzantine models and may even have been created by Byzantine craftsmen.

Although it is common today to associate global networks with the modern period, intercultural connections were also a vital part of ancient, late antique, and medieval experience in Afro-Eurasia. The Byzantine Empire communicated with diverse cultures and societies, and the art, architecture, and material culture of Byzantium and its neighbors attest eloquently to this interconnected reality.

Notes:

[1] Anthea Harris, ed., Incipient Globalization?: Long-distance Contacts in the Sixth Century (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007).

[2] Michael Bintley, “The Byzantine Silver Bowls in the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial and Tree-Worship in Anglo-Saxon England,” Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 21 (2011): 34–45.

Additional resources

G. W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, and Oleg Grabar, Late antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World(Cambridge, Mass.; London, Eng.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999).

Nicola Di Cosmo and Michael Maas, Empires and exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Helen C. Evans and Brandie Ratliff, Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).