23

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

Constantinople

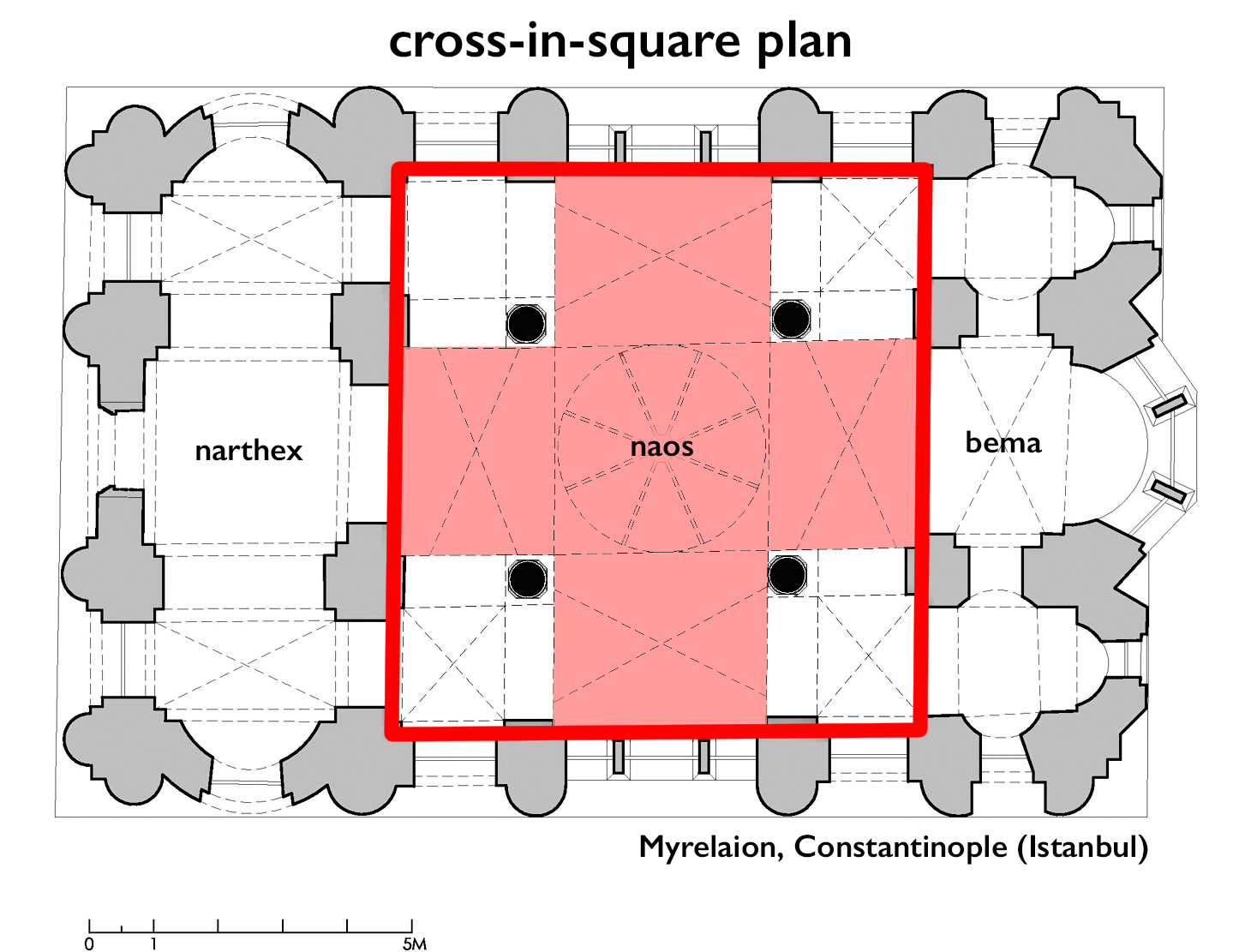

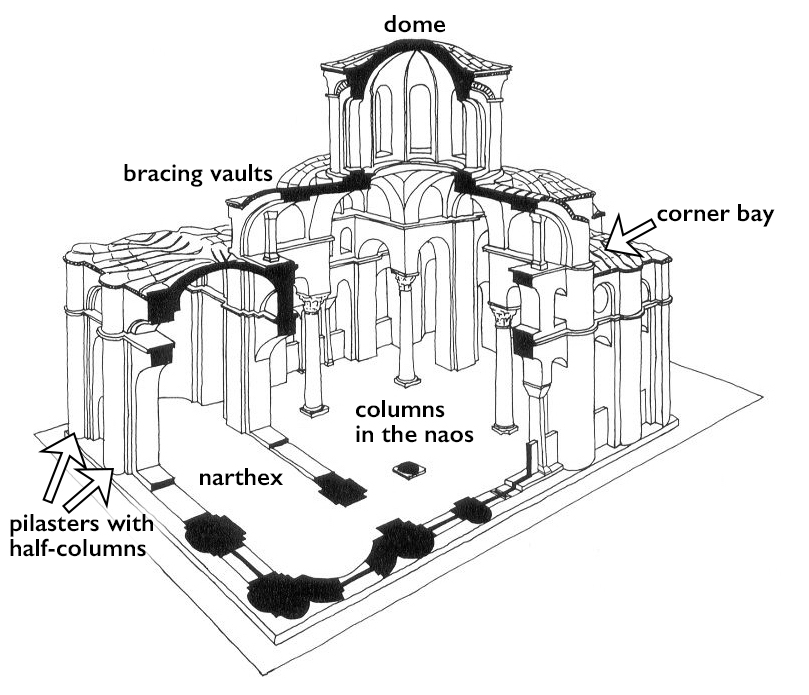

Churches in Constantinople from the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843–1204), such as the tenth-century cross-in-square Myrelaion church exhibit a balance between their various components: normally in the plan, the tripartite sanctuary (or bema) is balanced by the narthex (the entry vestibule preceding the nave), and on the exterior the structural divisions are emphasized by pilasters (a rectangular column that projects from a wall). In the case of the Myrelaion, half-columns have been affixed to pilasters.

Some surface ornament occurs but it is usually limited, and in many instances exterior surfaces of churches may have been plastered.

On the interior, groin vaults (arched structures formed by the intersection of two barrel vaults) and ribbed or pumpkin domes created undulating surfaces for mosaic decoration. However, the present appearance of the interior of the Myrelaion reflects its conversion to a mosque following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

*

*

*

Pantokrator Monastery

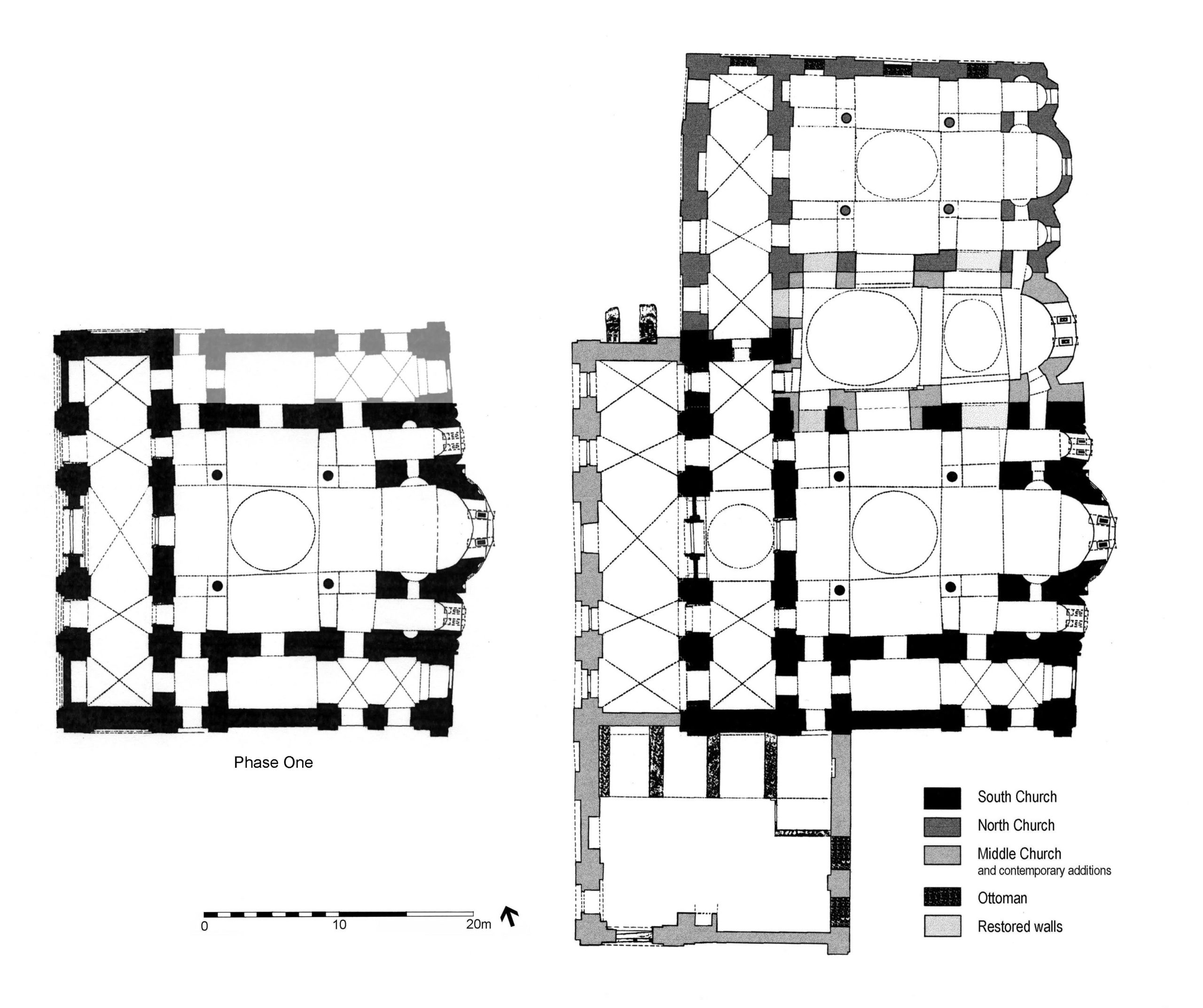

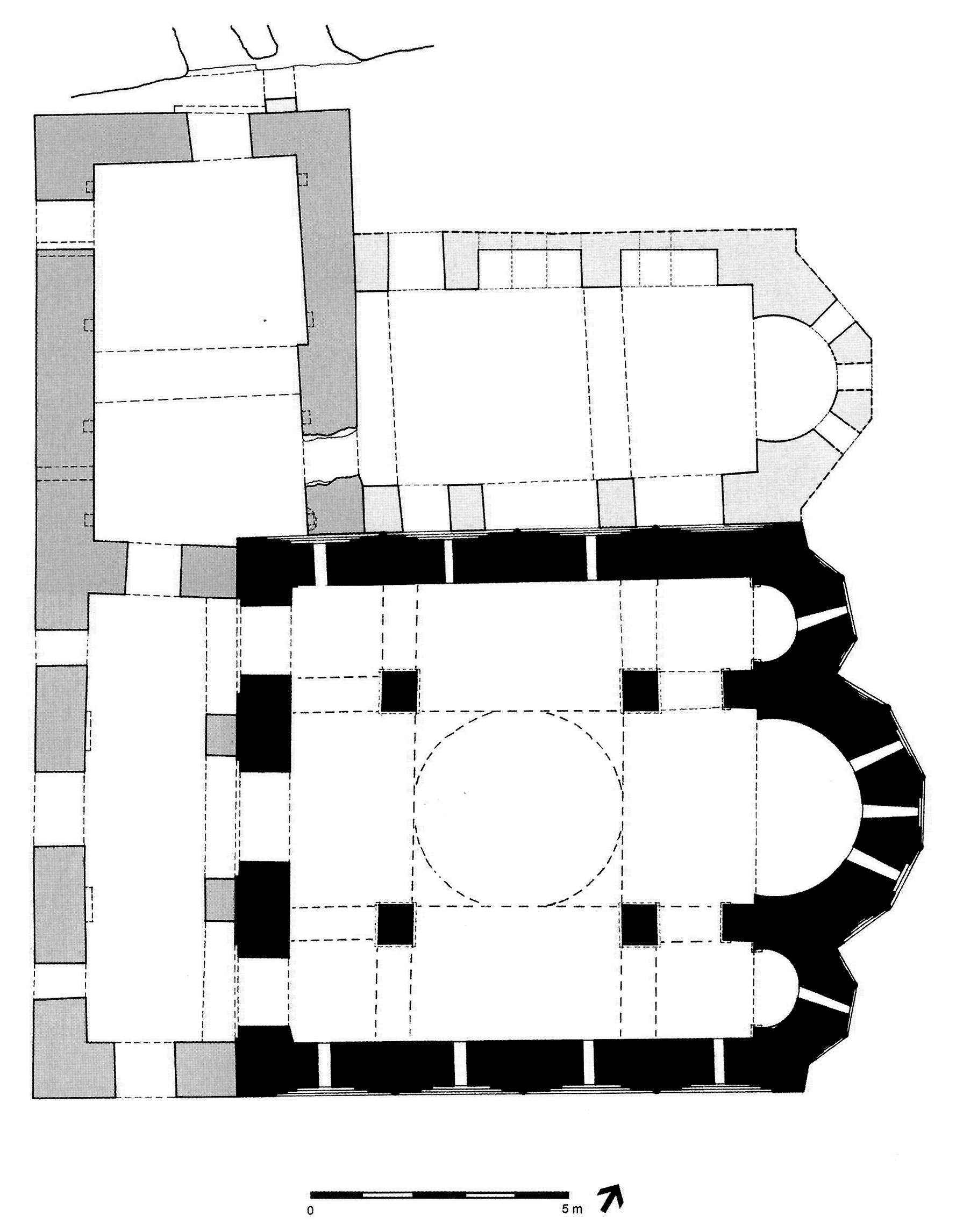

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, large imperially sponsored monastic complexes developed, in part as new settings for imperial and dynastic burials, as for example at the Pantokrator, built c. 1118–36 by John II and Eirene Komnenos. Three churches were built side by side in rapid succession (view plans below). The south church, dedicated to Christ Pantokrator, a large and lavishly decorated cross-in-square church, was the katholikon of the monastery; the north, also cross-in-square, was dedicated to the Virgin Eleousa and served the lay community. The middle church was single-aisled and covered by two domes; dedicated to St. Michael, it functioned as the imperial mausoleum and was referred to as the heroon (an ancient Greek term for a monument or sanctuary dedicated to a hero) in the monastic typikon (foundation document).

Greece

Hosios Loukas Monastery

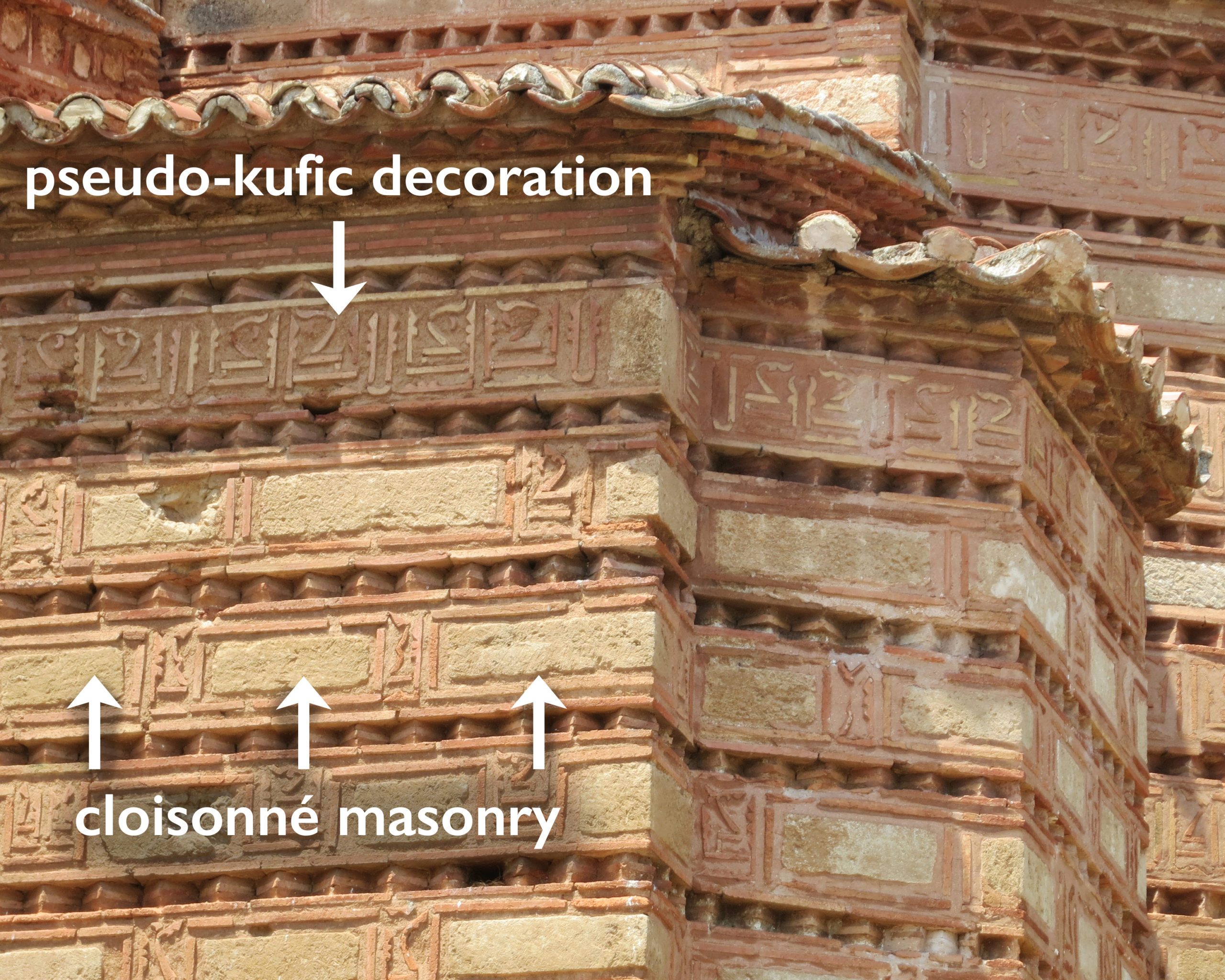

In mainland Greece, vault forms were often simpler, but exterior surfaces often lavishly decorated with cloisonné masonry (a technique where individual stones are framed with bricks) and pseudo-kufic decorations (motifs that imitate Arabic scripts) made of brick. The unusual Greek-cross-octagon plan, best known in the katholikon church at Hosios Loukas, inspired a number of regional examples.

Anatolia

Architecture flourished in central Anatolia (the large peninsula in West Asia, also known as “Asia Minor,” which makes up the majority of modern Turkey) until the Seljuq conquest of the 1070s. Distinctive masonry churches are preserved in Cappadocia and Lycaonia, but they have been overshadowed in the scholarship by the hundreds of well-preserved rock-cut churches, most notably those at Göreme, with their well-preserved painted programs, as at Karanlık Kilise. Most of these follow standardized designs, as developed in masonry architecture, but with some inventiveness evident in the detailing.

Çanlı Kilise

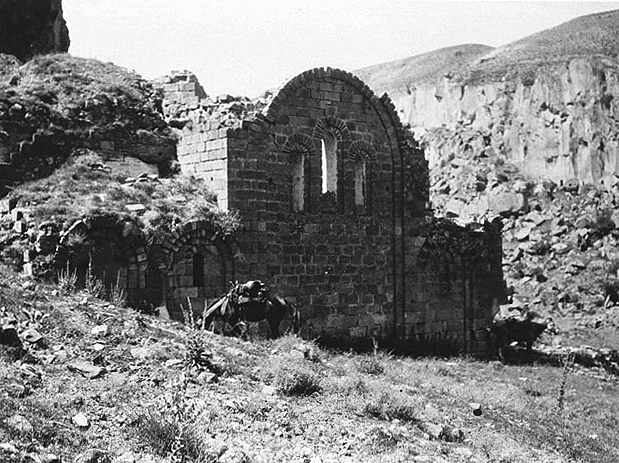

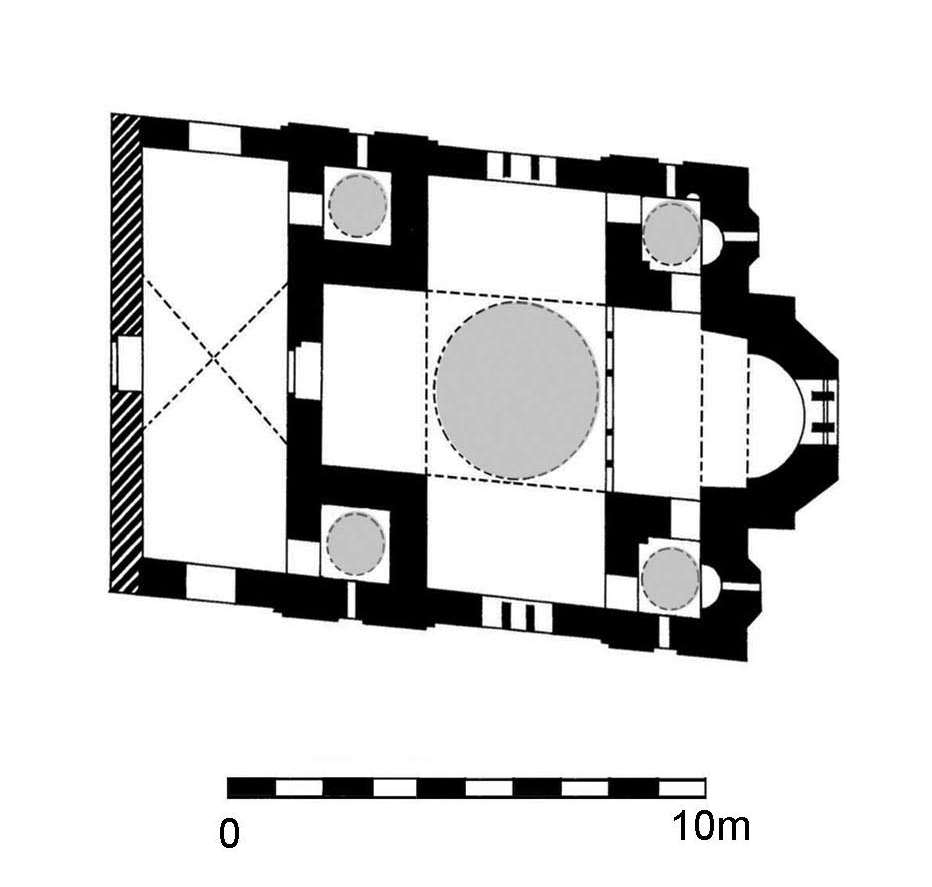

The cross-in-square church at the Çanlı Kilise (view plan at right) is carefully constructed of brick and stone, with design features suggesting an awareness of architecture from both Constantinople and the Caucasus (the area situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, today mainly occupied by Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Russia).

Armenia

Cathedral of Ani

Both Armenia and Georgia witnessed a revival of architecture in the tenth century. At Ani, the builder Trdat (responsible for rebuilding the dome of H. Sophia in Constantinople) built the cathedral as a domed basilica, as well as a church dedicated to St. Gregory, an aisled tetraconch following the model of Zvartnots, which is now in ruins.

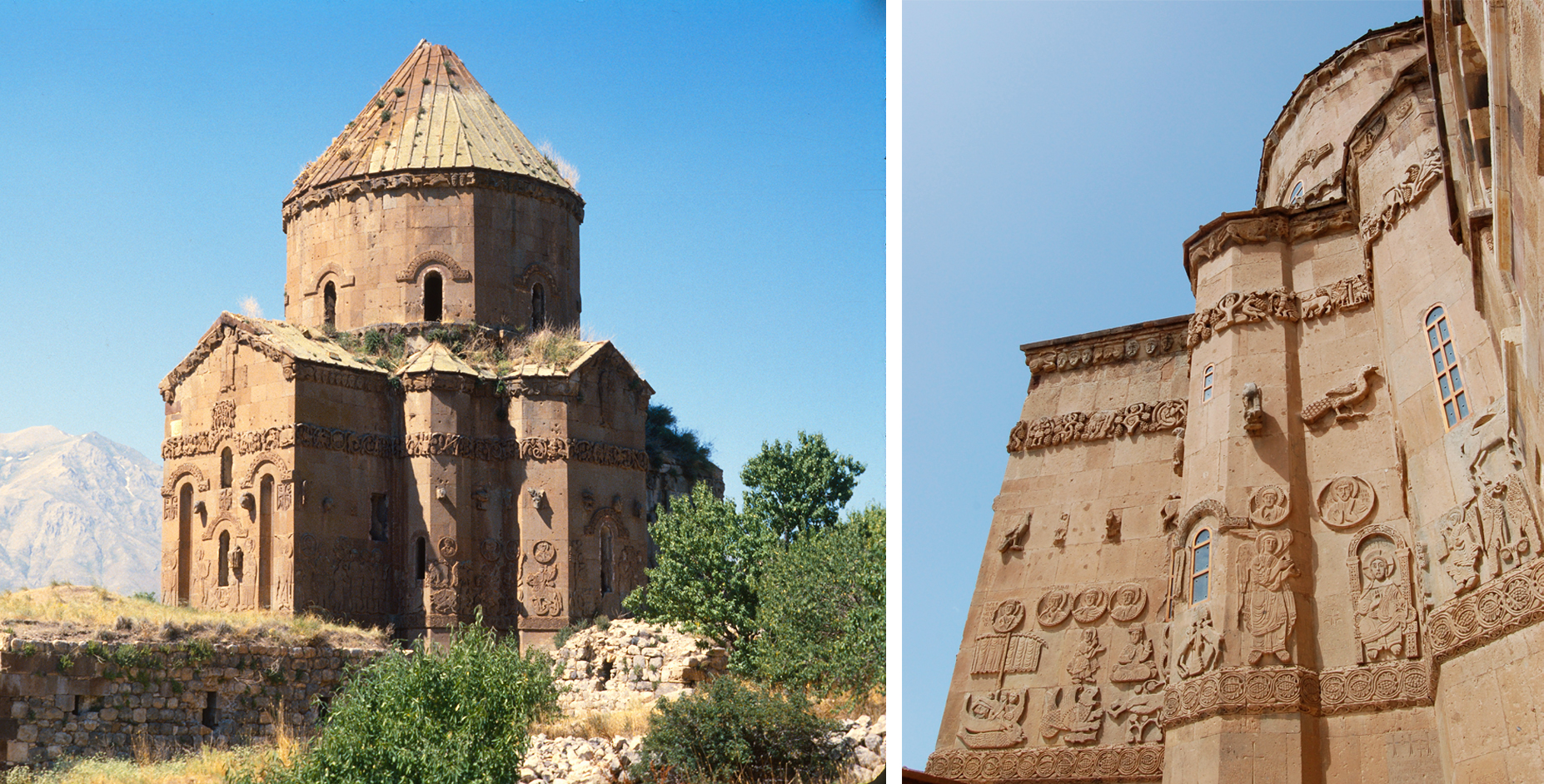

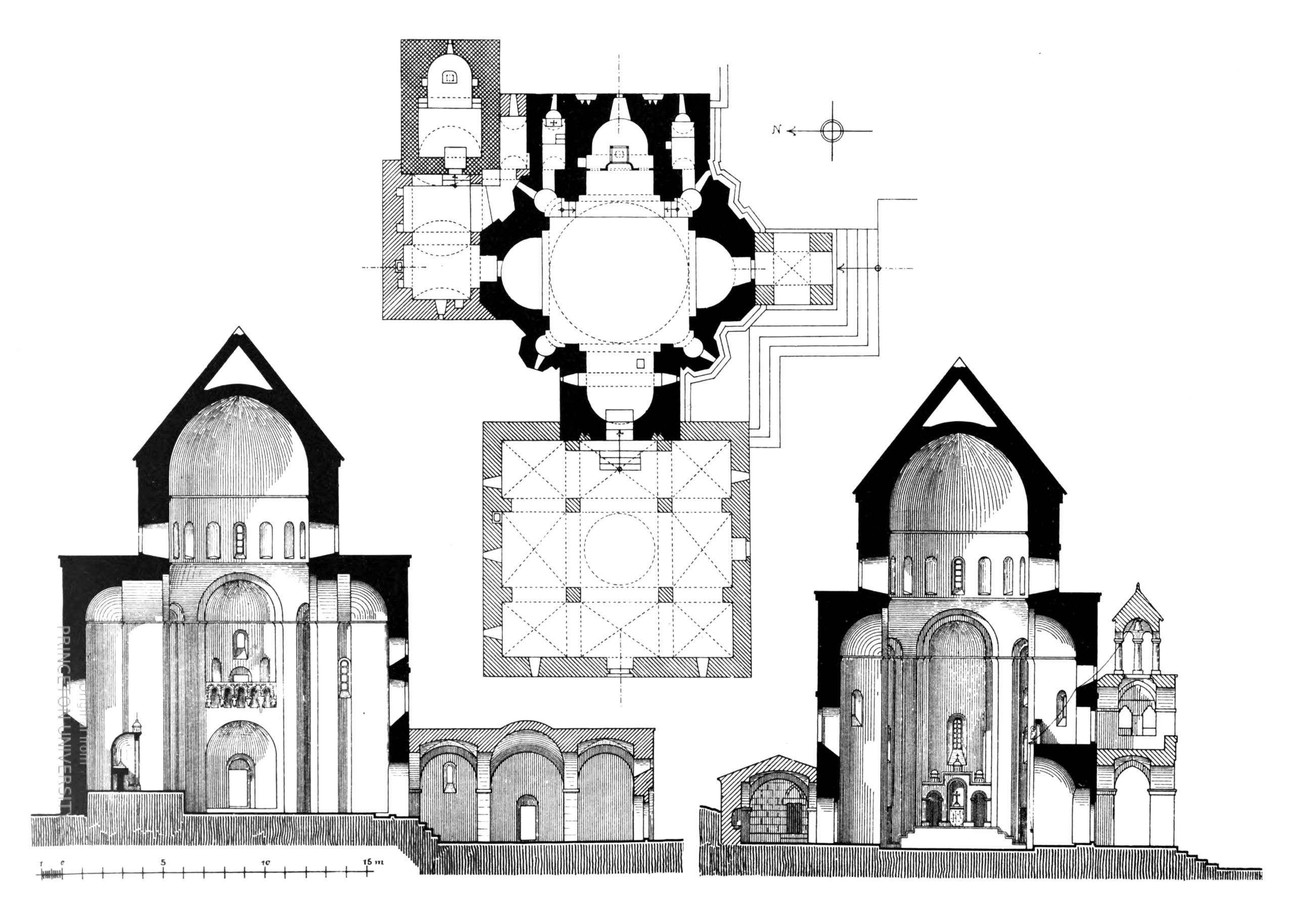

Church of the Holy Cross at Ahtamar

The octagon-dome palace church of the Holy Cross at Ahtamar (915–21) (view plan and sections below) follows earlier models but was lavishly decorated with external sculpture in contrast with most contemporary Byzantine churches.

*

Georgia

In the Tao-Klarjeti region (today located in northeastern Turkey and southwestern Georgia), several large domed basilicas were built in the late 10th and early 11th centuries, as at Öşk Vank, built c. 963–73 (view plan below), and İşhan, completed c. 1032; both are lavishly decorated with exterior sculpture, while the interiors display unusual vault forms. Ot‘ht‘a Eklesia, built at the same time is a grand, barrel-vaulted basilica. (A barrel vault is a type of ceiling that forms a half cylinder). All are of distinctive stone construction.

Serbia and Bulgaria

In general, the church architecture of Serbia and Bulgaria in this period betrays close associations with Greece and Constantinople. The five-domed church of Sv. Panteleimon at Nerezi, built 1164 and well known for its exquisite frescos, is certainly inspired by the architecture of the capital, as is Sv. Nikola at Kuršumlija. The design of the latter example was subsequently followed at Studenica and Djurdjevi Stupovi (now heavily restored). Several large and distinctive basilicas were constructed to meet the demands of congregational worship, as at Sv. Sofia in Ohrid, constructed c. 1000, or the church at Pliska.

Kievan Rus’

St. Sophia in Kiev

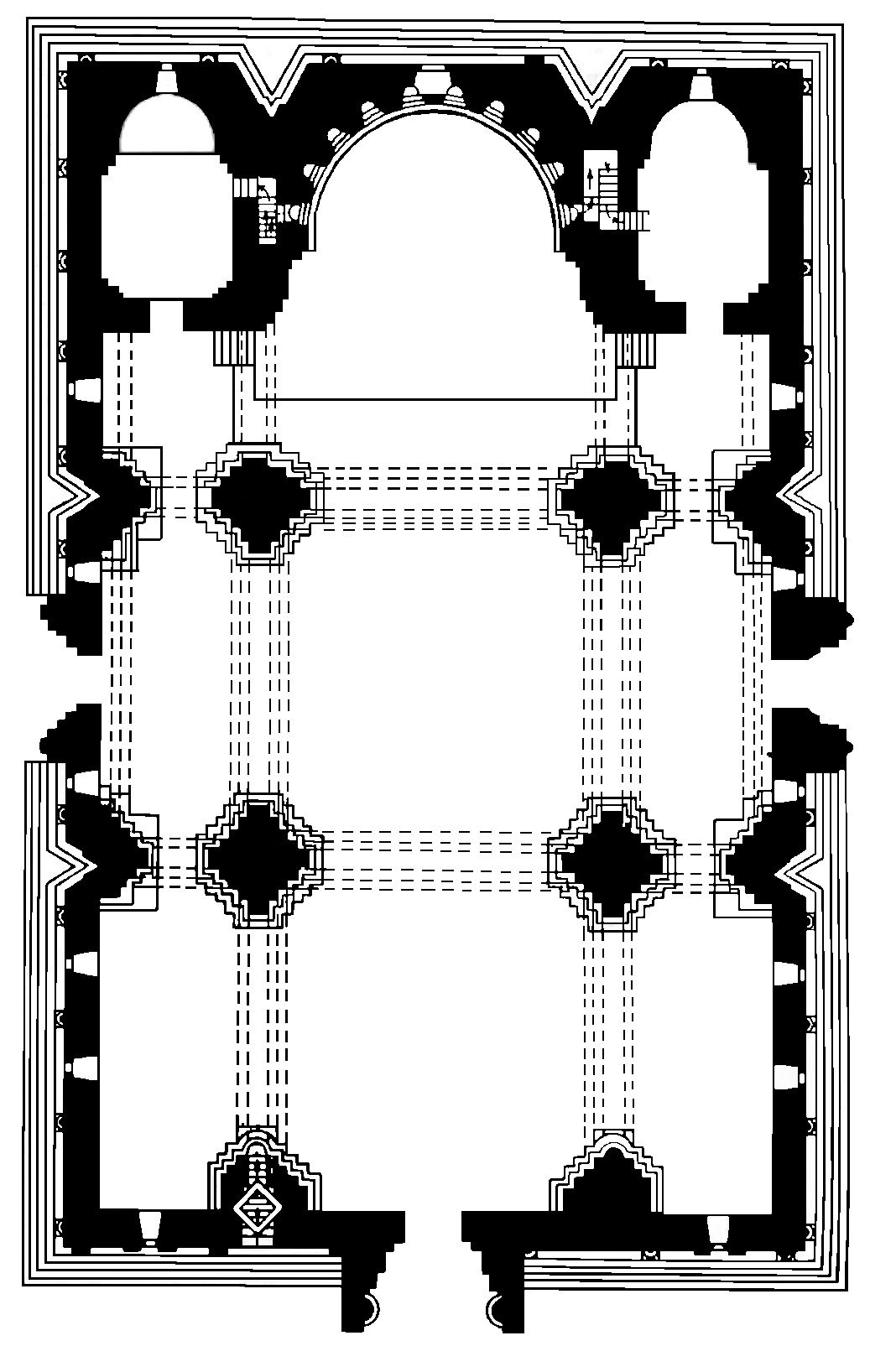

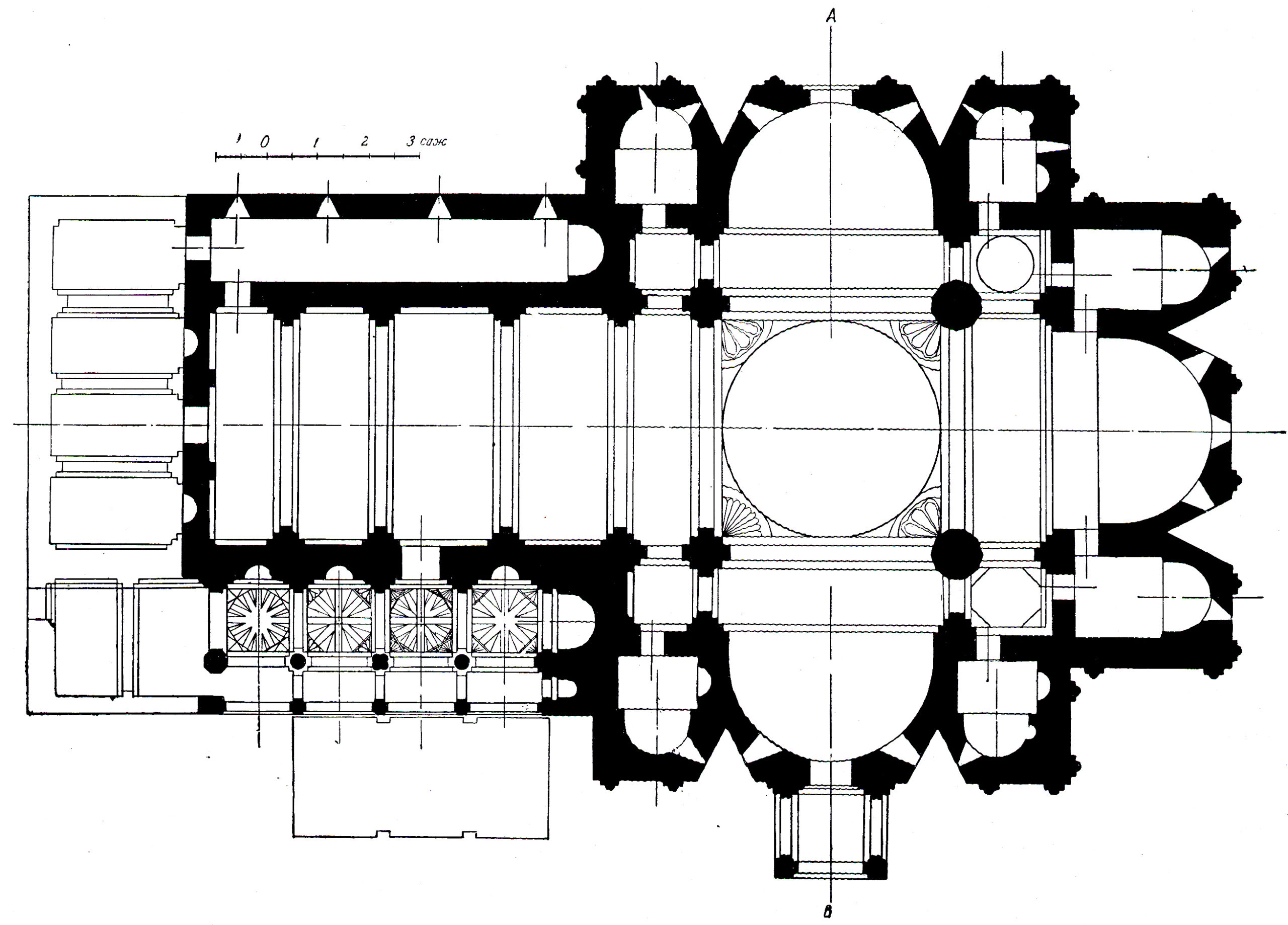

After Kievan Rus’ was Christianized in 988, it similarly required large congregational churches for the recently converted population. At St. Sophia in Kiev, begun 1037, and elsewhere, imported Byzantine masons familiar with the structural systems of the small, vaulted churches, elaborated a basic Middle Byzantine scheme, enveloping the tall domed core of the building with a series of ambulatories (a circular hallway outside a central space) and galleries (view plan below). These increased the interior space from what would have provided ample room for the private devotions of a few individuals to what was necessary for a large congregation. Following the initial impetus from Byzantium, however, as the center of power shifted northward, Russia looked to the Romanesque architecture of northern Europe for inspiration, while maintaining the attenuated cross-in-square church as the standard type, as occurs at several twelfth-century churches in and around Vladimir.

Monasteries

Monasteries of the Middle Byzantine period commonly had the church as the central element, freestanding within a walled enclosure, the latter lined with the monastic cells and other buildings. Often the refectory (where the monks took their meals) was set in relationship to the church building, either opposite or parallel to it. With most surviving examples, however, the original church building is preserved, but the other buildings have undergone numerous reconstruc- tions, as at Hosios Meletios, Hosios Loukas, and the monasteries on Mount Athos, as well as at Studenica in Serbia (see image below).

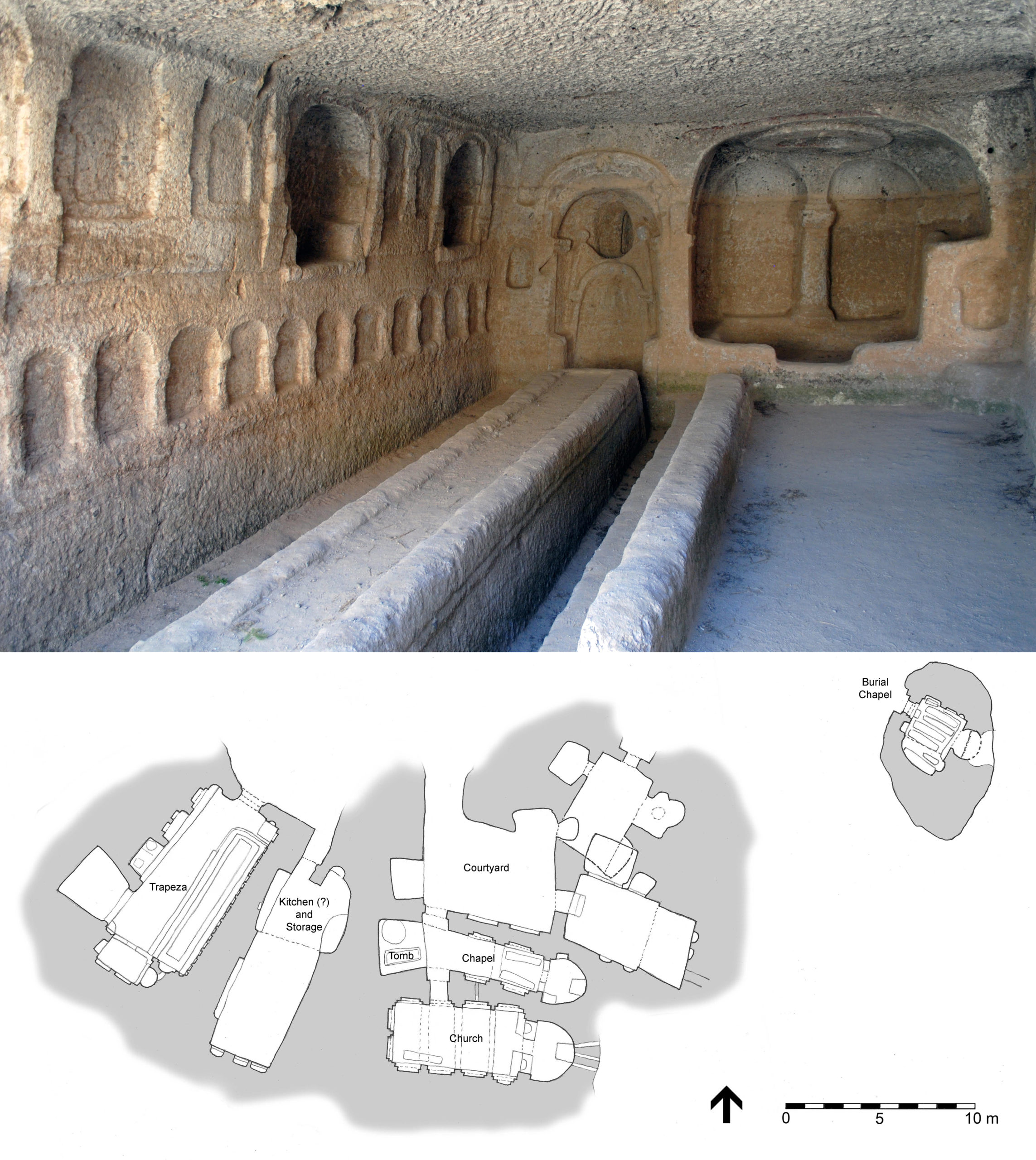

Because of the site specificity and long construction history, it remains difficult to determine a “standard” Middle Byzantine monastery type. There are also numerous well-preserved examples of monasteries in Cappadocia. At Göreme a cluster of small monastic ensembles developed in the Middle Byzantine period, each equipped with its own church or chapel and a trapeza with a rock-cut table and benches. (“Trapeza,” Greek for “table,” refers to the refectory, or dining hall, of a monastery.) The trapeza at the Geyikli Kilise complex in the Soğanlı Valley is lavishly carved. Planning in these examples, however, was by necessity site-specific and often similar to domestic complexes.

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

*