1

Dr. Evan Freeman

This essay introduces the periods of Byzantine history, with attention to developments in art and architecture.

From Rome to Constantinople

In 313, the Roman Empire legalized Christianity, beginning a process that would eventually dismantle its centuries-old pagan tradition. Not long after, emperor Constantine transferred the empire’s capital from Rome to the ancient Greek city of Byzantion (modern Istanbul). Constantine renamed the new capital city “Constantinople” (“the city of Constantine”) after himself and dedicated it in the year 330. With these events, the Byzantine Empire was born—or was it?

The term “Byzantine Empire” is a bit of a misnomer. The Byzantines understood their empire to be a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire and referred to themselves as “Romans.” The use of the term “Byzantine” only became widespread in Europe after Constantinople finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. For this reason, some scholars refer to Byzantium as the “medieval Roman” or “Eastern Roman” Empire.

Byzantine History

The history of Byzantium is remarkably long. If we reckon the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from the dedication of Constantinople in 330 until its fall to the Ottomans in 1453, the empire endured for some 1,123 years.

Scholars typically divide Byzantine history into three major periods: Early Byzantium, Middle Byzantium, and Late Byzantium. But it is important to note that these historical designations are the invention of modern scholars rather than the Byzantines themselves. Nevertheless, these periods can be helpful for marking significant events, contextualizing art and architecture, and understanding larger cultural trends in Byzantium’s history.

Early Byzantium: c. 330–843

Scholars often disagree about the parameters of the Early Byzantine period. On the one hand, this period saw a continuation of Roman society and culture—so, is it really correct to say it began in 330? On the other, the empire’s acceptance of Christianity and geographical shift to the east inaugurated a new era.

Following Constantine’s embrace of Christianity, the church enjoyed imperial patronage, constructing monumental churches in centers such as Rome, Constantinople, and Jerusalem. In the west, the empire faced numerous attacks by Germanic nomads from the north, and Rome was sacked by the Goths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455. The city of Ravenna in northeastern Italy rose to prominence in the 5th and 6th centuries when it functioned as an imperial capital for the western half of the empire. Several churches adorned with opulent mosaics, such as San Vitale and the nearby Sant’Apollinare in Classe, testify to the importance of Ravenna during this time.

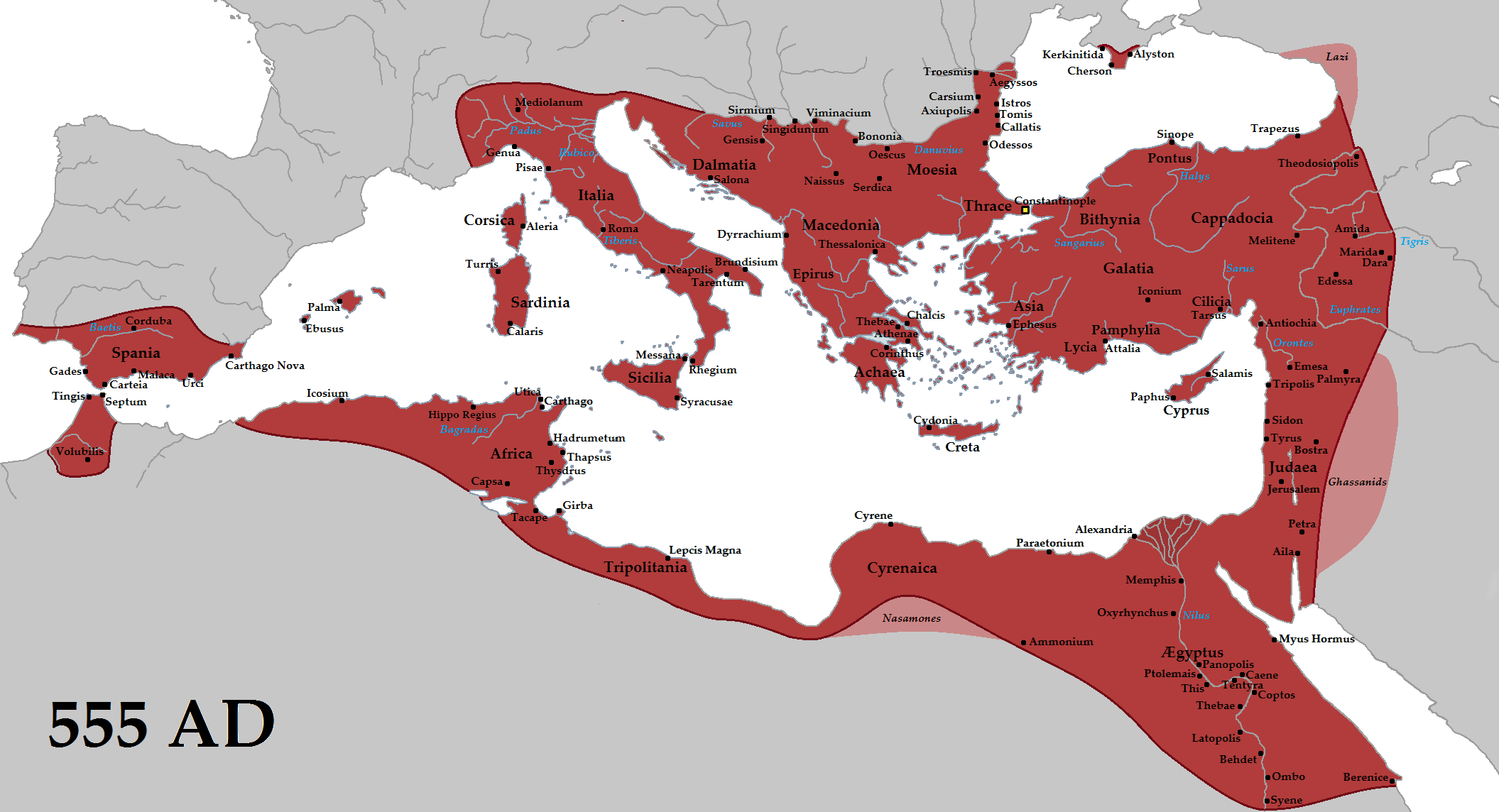

Under the sixth-century emperor Justinian I, who reigned 527–65, the Byzantine Empire expanded to its largest geographical area: encompassing the Balkans to the north, Egypt and other parts of north Africa to the south, Anatolia (what is now Turkey) and the Levant (including including modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan) to the east, and Italy and the southern Iberian Peninsula (now Spain and Portugal) to the west. Many of Byzantium’s greatest architectural monuments, such as the innovative domed basilica of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, were also built during Justinian’s reign.

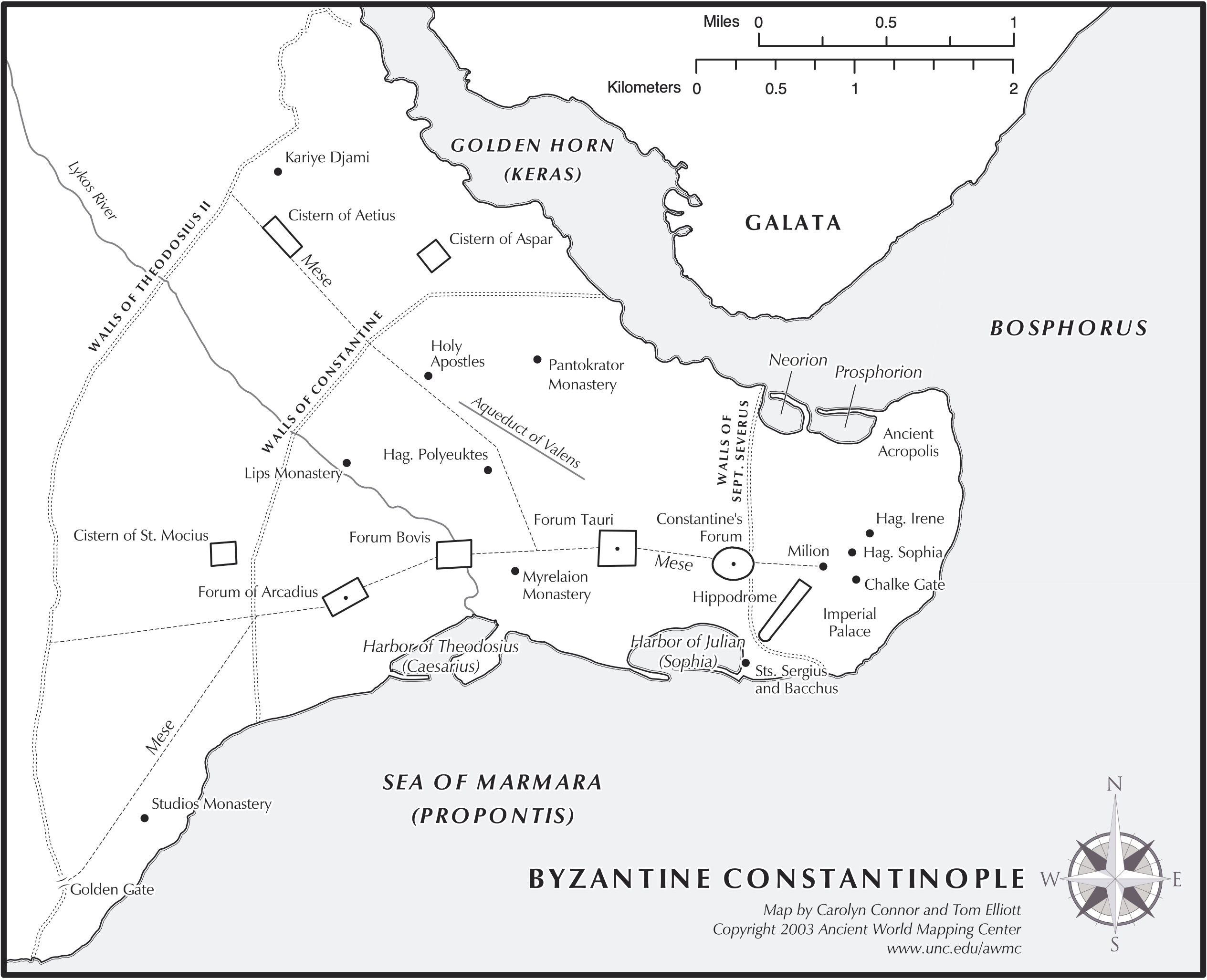

Following the example of Rome, Constantinople featured a number of outdoor public spaces —including major streets, fora (in ancient Roman urban planning, the city center: an open space used for markets and gatherings of citizens, surrounded by temples and public buildings), as well as a hippodrome (a course for horse or chariot racing with public seating)—in which emperors and church officials often participated in showy public ceremonies such as processions.

Christian monasticism, which began to thrive in the 4th century, received imperial patronage at sites like Mount Sinai in Egypt.

Yet the mid-7th century began what some scholars call the “dark ages” or the “transitional period” in Byzantine history. Following the rise of Islam in Arabia and subsequent attacks by Arab invaders, Byzantium lost substantial territories, including Syria and Egypt, as well as the symbolically important city of Jerusalem with its sacred pilgrimage sites. The empire experienced a decline in trade and an economic downturn.

Against this backdrop, and perhaps fueled by anxieties about the fate of the empire, the so-called “Iconoclastic Controversy” erupted in Constan- tinople in the 8th and 9th centuries. Church leaders and emperors debated the use of religious images that depicted Christ and the saints, some honoring them as holy images, or “icons,” and others condemning them as idols (like the images of deities in ancient Rome) and apparently destroying some. Finally, in 843, Church and imperial authorities definitively affirmed the use of religious images and ended the Iconoclastic Controversy, an event subsequently celebrated by the Byzantines as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” (Orthodoxy refers to right Christian belief, believed to be essential for salvation.)

Middle Byzantium: c. 843–1204

In the period following Iconoclasm, the Byzantine empire enjoyed a growing economy and reclaimed some of the territories it lost earlier. With the affirmation of images in 843, art and architecture once again flourished. But Byzantine culture also underwent several changes.

Middle Byzantine churches elaborated on the innovations of Justinian’s reign, but were often constructed by private patrons and tended to be smaller than the large imperial monuments of Early Byzantium. The smaller scale of Middle Byzantine churches also coincided with a reduction of large, public ceremonies.

Monumental depictions of Christ and the Virgin, biblical events, and an array of various saints adorned church interiors in both mosaics and frescoes. But Middle Byzantine churches largely exclude depictions of the flora and fauna of the natural world that often appeared in Early Byzantine mosaics, perhaps in response to accusations of idolatry during the Iconoclastic Controversy. In addition to these developments in architecture and monumental art, exquisite examples of manuscripts, cloisonné enamels, stonework, and ivory carving survive from this period as well.

The Middle Byzantine period also saw increased tensions between the Byzantines and western Europeans (whom the Byzantines often referred to as “Latins” or “Franks”). The so-called “Great Schism” of 1054 signaled growing divisions between Orthodox Christians in Byzantium and Roman Catholics in western Europe.

The Fourth Crusade and the Latin Empire: 1204–1261

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade—undertaken by western Europeans loyal to the pope in Rome—veered from its path to Jerusalem and sacked the Christian city of Constantinople. Many of Constantinople’s artistic treasures were destroyed or carried back to western Europe as booty. The crusaders occupied Constantinople and established a “Latin Empire” in Byzantine territory. Exiled Byzantine leaders established three successor states: the Empire of Nicaea in northwestern Anatolia, the Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia, and the Despotate of Epirus in northwestern Greece and Albania. In 1261, the Empire of Nicaea retook Constantinople and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos as emperor, establishing the Palaiologan dynasty that would reign until the end of the Byzantine Empire.

While the Fourth Crusade fueled animosity between eastern and western Christians, the crusades nevertheless encouraged cross-cultural exchange that is apparent in the arts of Byzantium and western Europe, and particularly in Italian paintings of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, exemplified by new depictions of St. Francis painted in the so-called Italo-Byzantine style.

Late Byzantium: 1261–1453

Artistic patronage again flourished after the Byzantines re-established their capital in 1261. Some scholars refer to this cultural flowering as the “Palaiologan Renaissance” (after the ruling Palaiologan dynasty). Several existing churches —such as the Chora Monastery in Constantinople—were renovated, expanded, and lavishly decorated with mosaics and frescoes. Byzantine artists were also active outside Constantinople, both in Byzantine centers such as Thessaloniki, as well as in neighboring lands, such as the Kingdom of Serbia, where the signatures of the painters named Michael Astrapas and Eutychios have been preserved in frescos from the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

Yet the Byzantine Empire never fully recovered from the blow of the Fourth Crusade, and its territory continued to shrink. Byzantium’s calls for military aid from western Europeans in the face of the growing threat of the Ottoman Turks in the east remained unanswered.

*

In 1453, the Ottomans finally conquered Constan- tinople, converting many of Byzantium’s great churches into mosques, and ending the long history of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Post-Byzantium: after 1453

Despite the ultimate demise of the Byzantine Empire, the legacy of Byzantium continued. This is evident in formerly Byzantine territories like Crete, where the so-called “Cretan School” of iconography flourished under Venetian rule (a famous product of the Cretan School being Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco).

But Byzantium’s influence also continued to spread beyond its former cultural and geographic boundaries, in the architecture of the Ottomans, the icons of Russia, the paintings of Italy, and elsewhere.

*