6

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

Basilicas and new forms

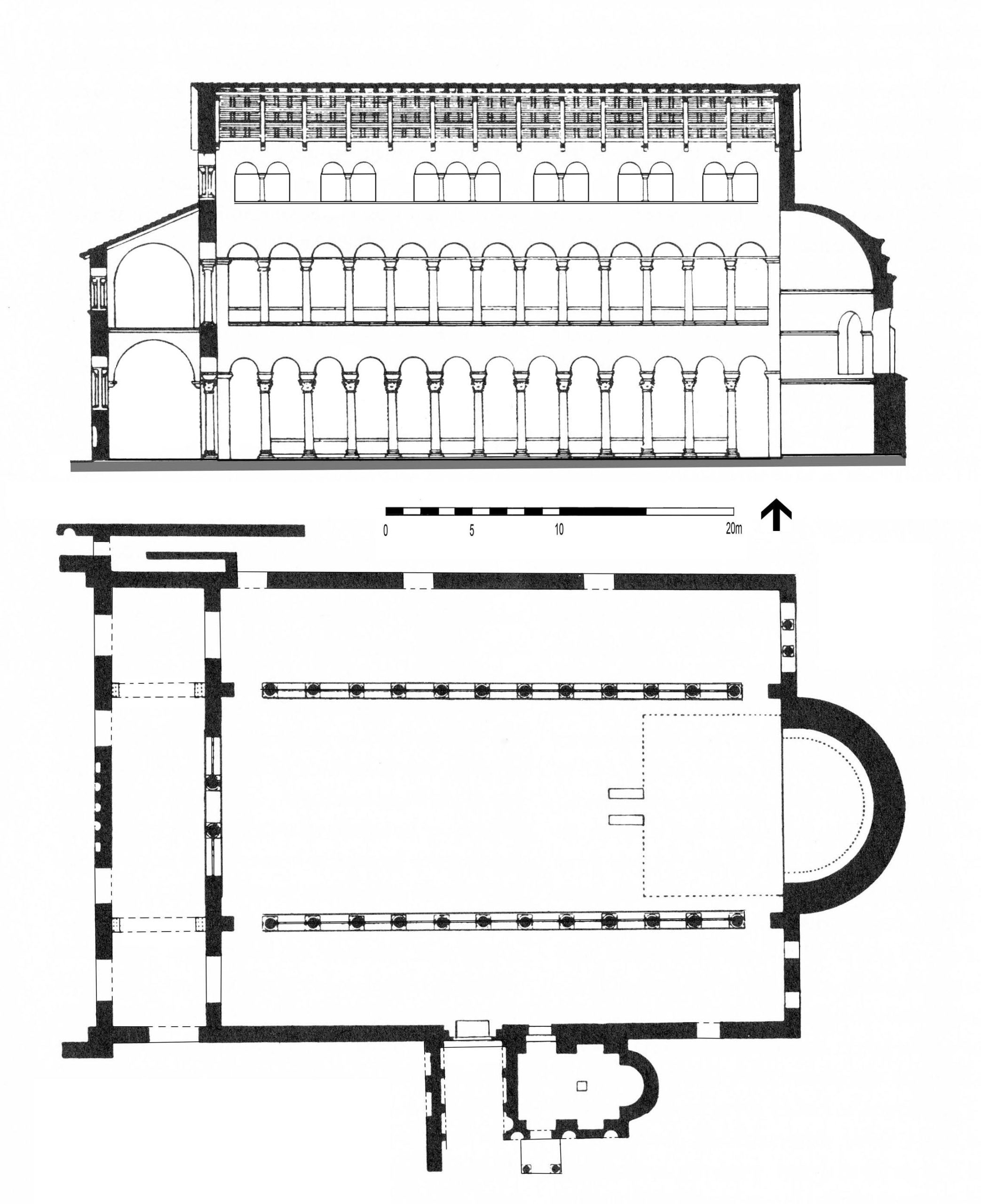

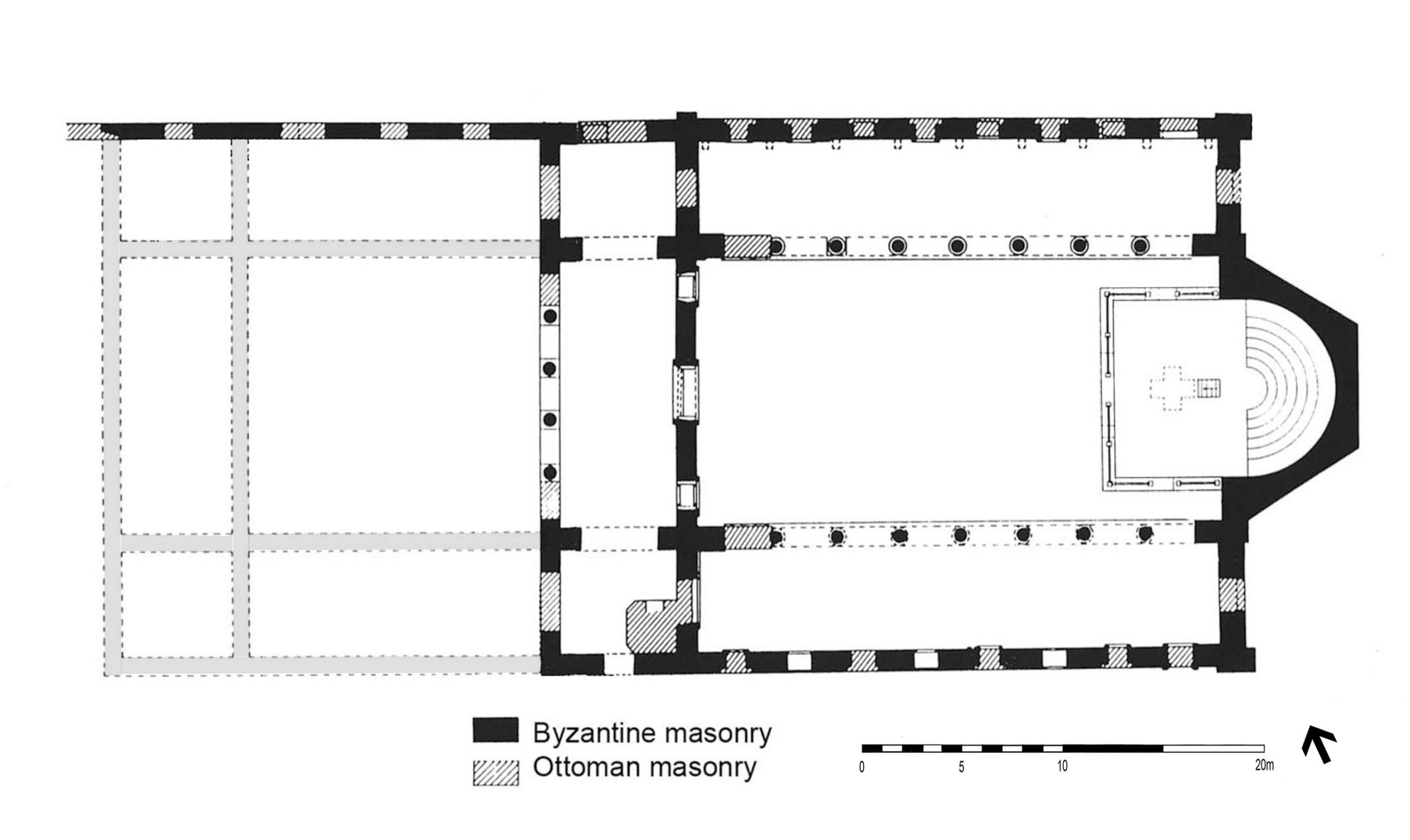

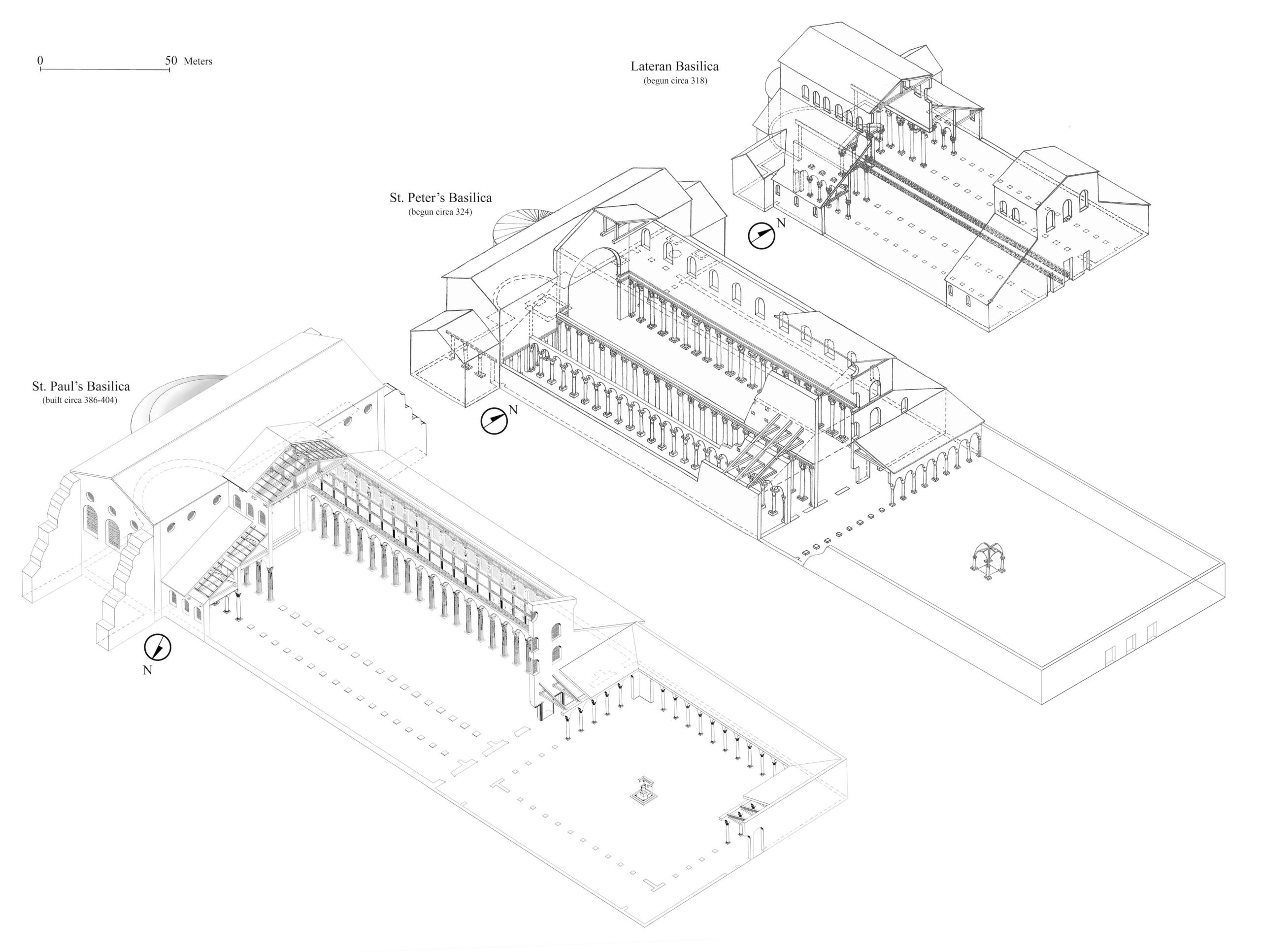

After the time of Constantine, the Roman emperor who ruled from 306–337 C.E., a standardized church architecture emerged, with the basilica for congregational worship dominating construction. The basilica is a church type based on Roman assembly halls, usually composed of a longitudinal nave flanked by side aisles.

*

There were numerous regional variations: in Rome and the West, for example, basilicas usually were elongated without galleries, as at S. Sabina in Rome (522–32) or S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (c. 490). (The gallery is the upper level in a church, above the side aisles and narthex, where worshippers could participate in church services.)

In the East the buildings were more compact and galleries were more common, as at St. John Stoudios in Constantinople (458) or the Achieropoiitos in Thessaloniki (early fifth century).

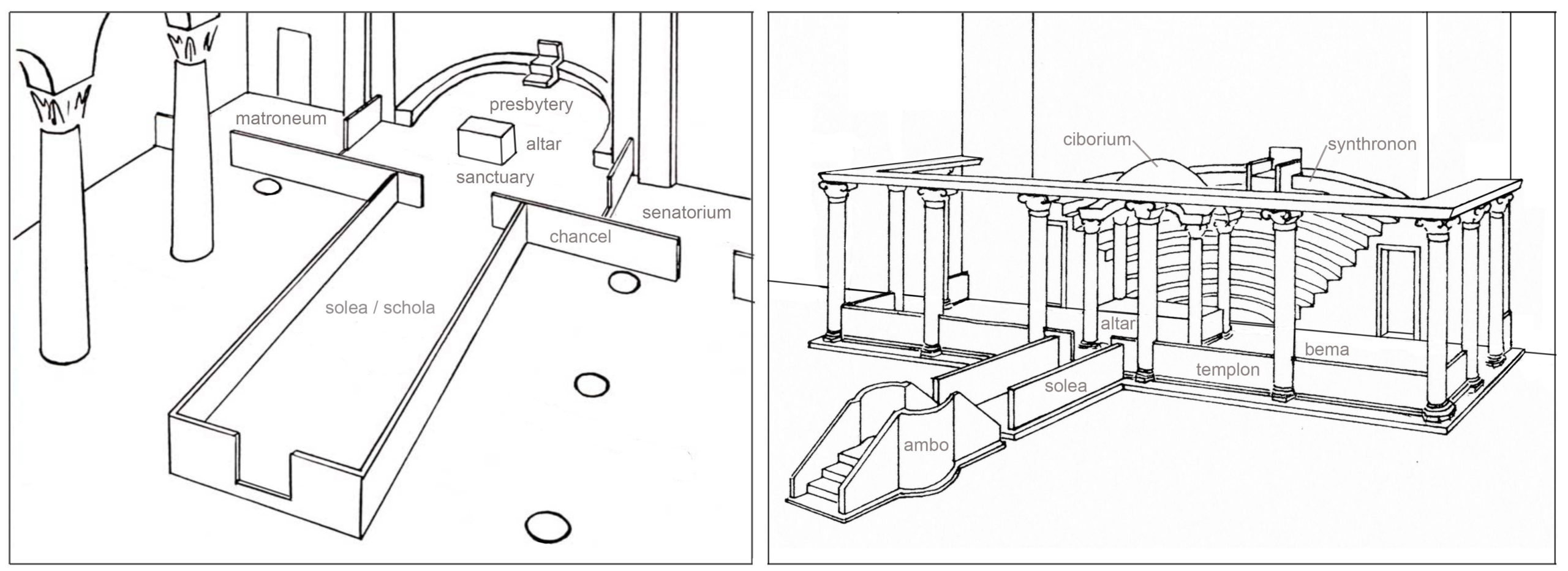

By the fifth century, the liturgy had become standardized, but, again, with some regional variations, evident in the planning and furnishing of basilicas. In general, the area of the altar was enclosed by a templon barrier (a screen separating the nave or naos from the sanctuary, also called a chancel barrier), with semicircular seating for the officiants (the synthronon) in the curvature of the apse (a semicircular recess, usually terminating the longitudinal axis of a church, containing the altar). The altar itself was covered by a ciborium, a canopy raised above an altar, throne, or tomb (also called a baldachin). Within the nave, a raised pulpit or ambo provided a setting for the Gospel readings.

The liturgy probably had less effect on the creation of new architectural designs than on the increasing symbolism and sanctification of the church building. Some new building types emerge, such as the cruciform (cross-shaped) church, the tetraconch (a building with four apses), octagon (eight-sided shape), and a variety of centrally planned structures.

Such forms may have had symbolic overtones. For example, the cruciform plan may be either a reflection of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople (a nonextant cruciform church of Constantinople first built by Constantine’s sons and rebuilt in the sixth century under emperor Justinian I that contained relics of some of the Apostles and incorporated mausolea where Byzantine emperors were buried until 1028) or associated with the life-giving cross, as at S. Croce in Ravenna or SS. Apostoli in Milan. Other innovative designs may have had their origins in architectural geometry, such as the enigmatic S. Stefano Rotondo (468–83) in Rome.

The aisled tetraconch churches, once thought to be a form associated with martyria (tomb of a martyr or a site that bears witness to the Christian faith), are most likely cathedrals or metropolitan churches. The early fifth-century tetraconch in the Library of Hadrian in Athens was probably the first cathedral of the city; that at Selucia Pieria-Antioch, from the late fifth century, was possibly a metropolitan church.

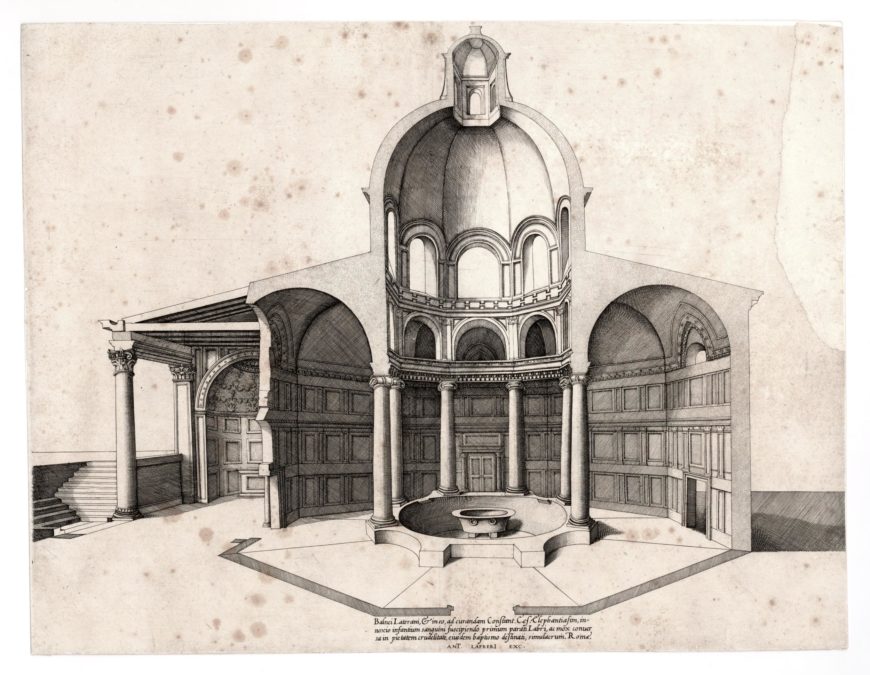

Baptisteries

Baptisteries, buildings containing a font for Christian initiation, are also prominent throughout the Empire, necessary for the elaborate ceremonies addressed to adult converts and catechumens. Most common was a symbolically resonant, octagonal building housing the font and attached to the cathedral, as with the Orthodox (or Neonian) Baptistery at Ravenna, c. 400–450. In Rome, the Lateran’s baptistery was an independent, octagonal structure that stood north of the basilica’s apse. Built under Constantine, the baptistery expanded under Pope Sixtus III in the fifth century with the addition of an ambulatory around its central structure.

The inscription St. Ambrose composed for his baptistery at Milan clarifies the symbolism of such eight-sided buildings:

The eight-sided temple has risen for sacred purposes

The octagonal font is worthy for this task.

It is seemly that the baptismal hall should arise in this number

By which true health returns to people

By the light of the resurrected Christ–inscription attributed to St. Ambrose of Milan

Associated with death and resurrection, the planning type derives from Late Roman mausolea (a monumental building for burial), although not directly from the Anastasis Rotunda (a circular structure enclosing Christ’s Tomb at the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem). Variations abound: at Butrint (in modern Albania) and Nocera (in southwestern Italy), for example, the baptisteries have ambulatories; in North Africa, the architecture tends to remain simple, while the form of the font is elaborated. With the change to infant baptism and a simplified ceremony, however, monumental baptisteries cease to be constructed after the sixth century.

Martyria and Mausolea

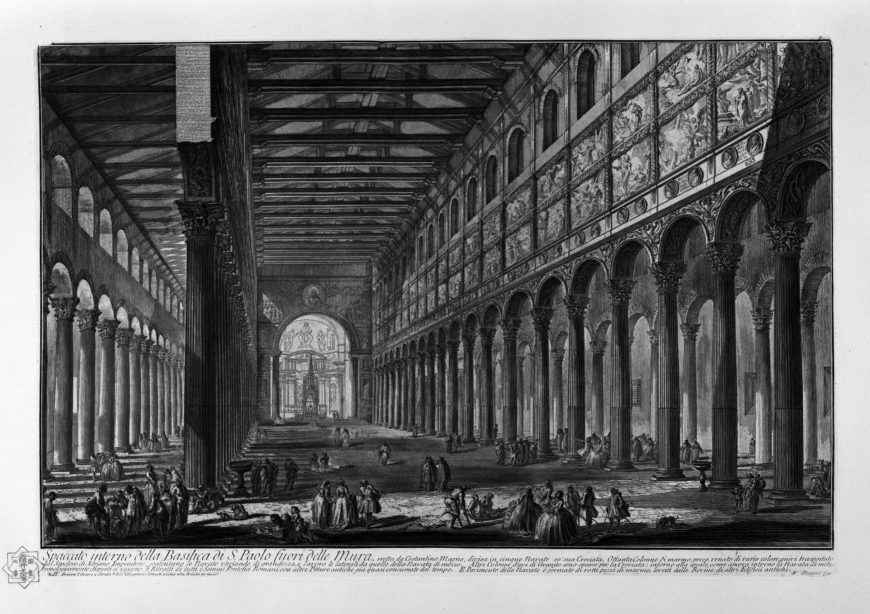

Although the church gradually eliminated the great funeral banquets at the graves of martyrs, the cult of martyrs was manifest in other ways, notably the importance of pilgrimage and the dissemination of relics (remains of saints or objects considered holy because they touched the bodies of saints). In spite of this, there was not a standard architectural form for the martyria, which instead seem to depend on site-specific conditions or regional developments. In Rome, for example, S. Paolo fuori le mura (St. Paul Outside the Walls), begun 384, follows the model of St. Peter’s in adding a transept to a huge five-aisled basilica.

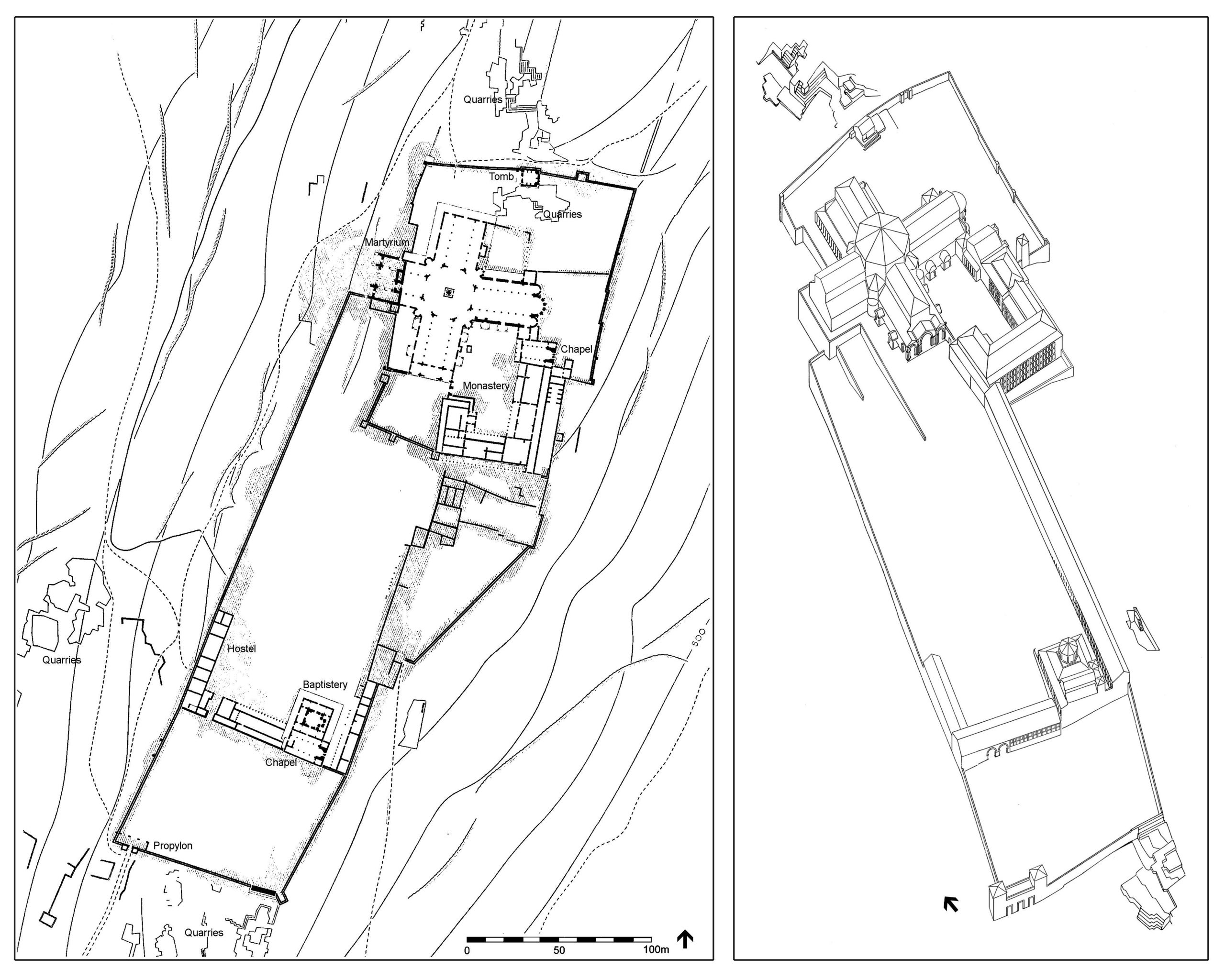

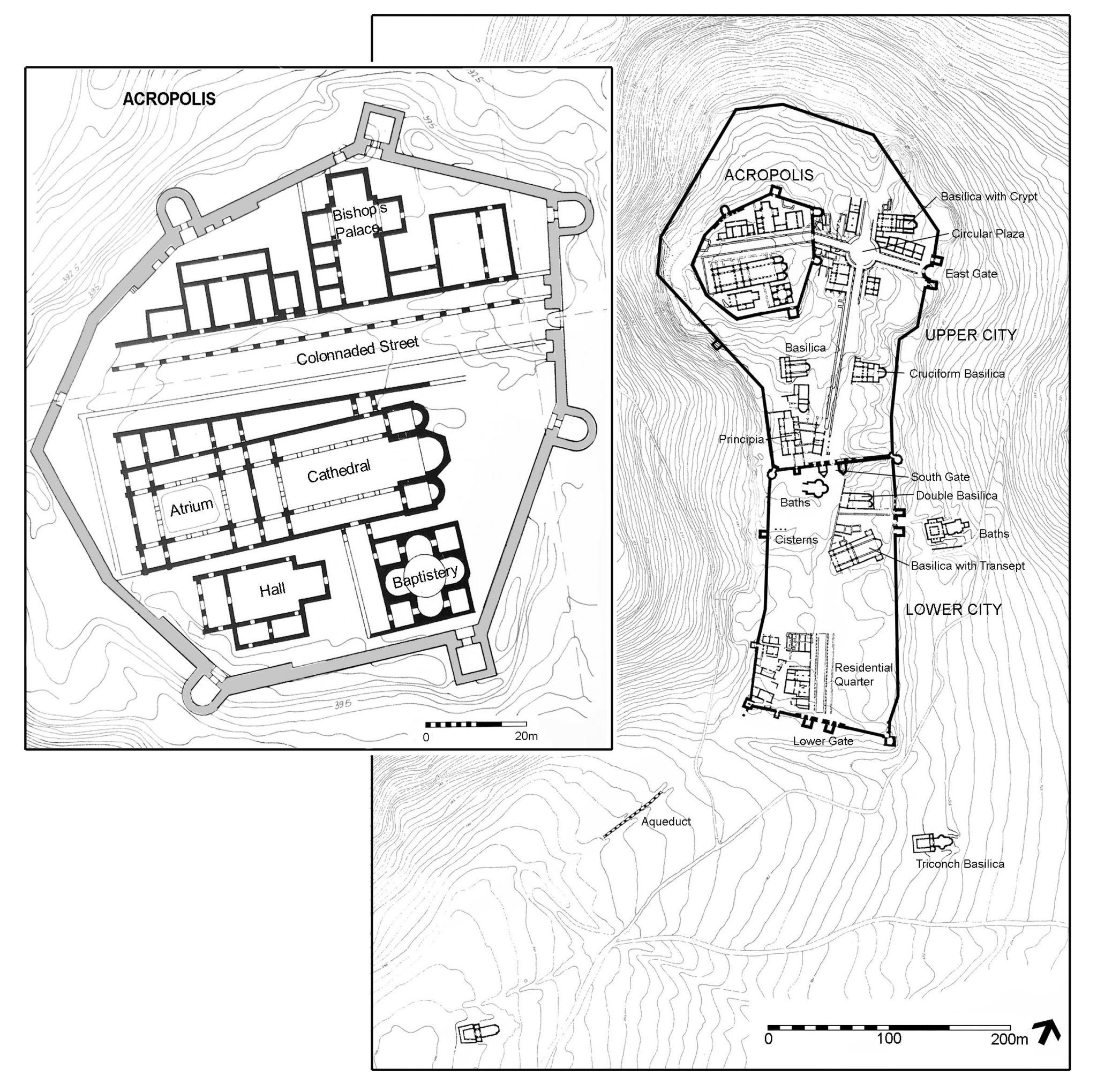

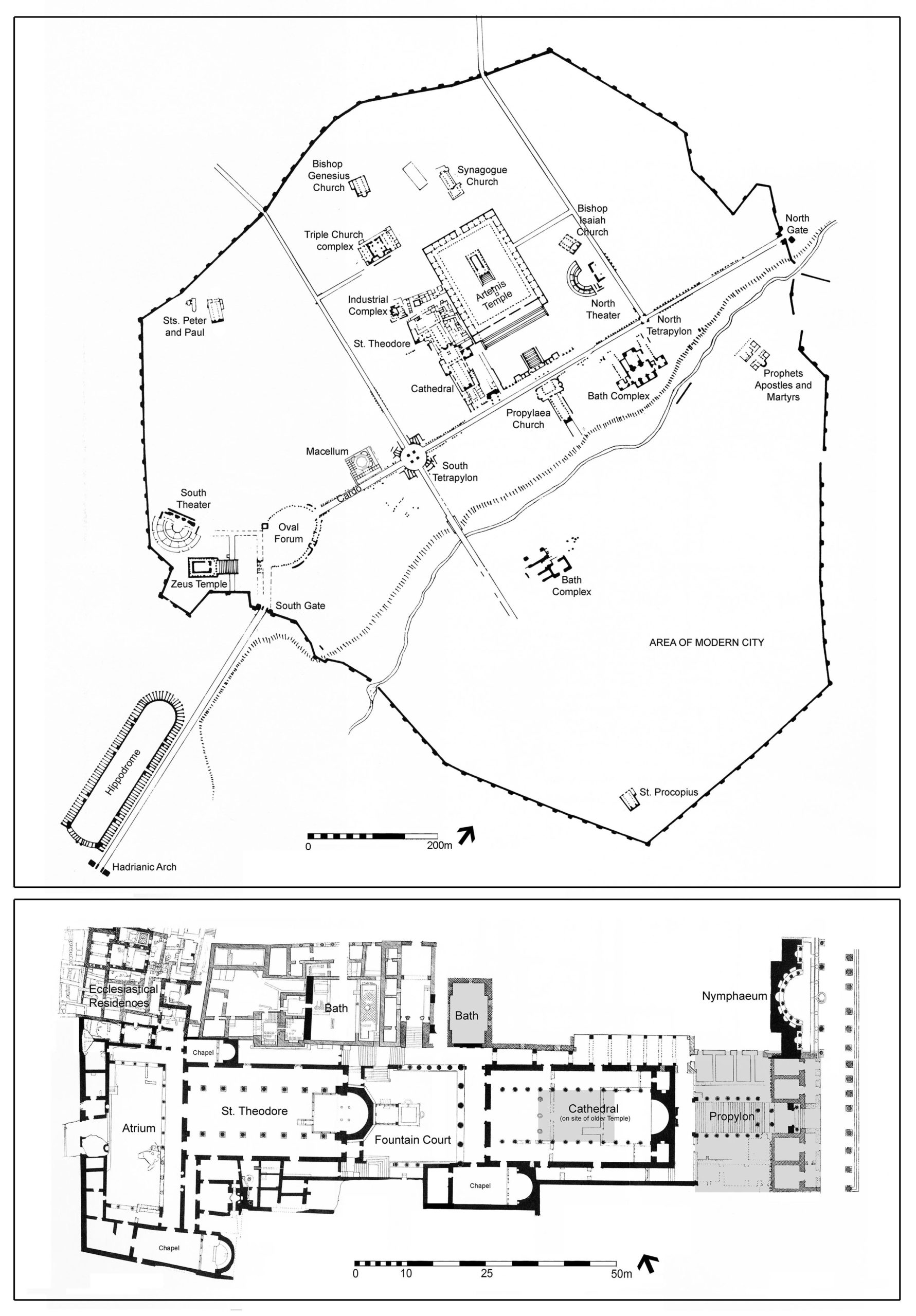

At Thessaloniki, the basilica of H. Demetrios (late fifth century) incorporated the remains of a crypt and other structures associated with the Roman bath where Demetrius was martyred.At rural locations, large complexes emerged, as at Qal’at Sem’an, built c. 480–90 in Syria, which had four basilicas radiating from an octagonal core, where the stylite saint’s column stood. Stylite saints lived atop pillars (stylos is Greek for “pillar”) as a means of self denial. (See plan below.)

An entire city (Abu Mena), with church architecture of increasing complexity, grew around the venerated tomb of St. Menas in Egypt.

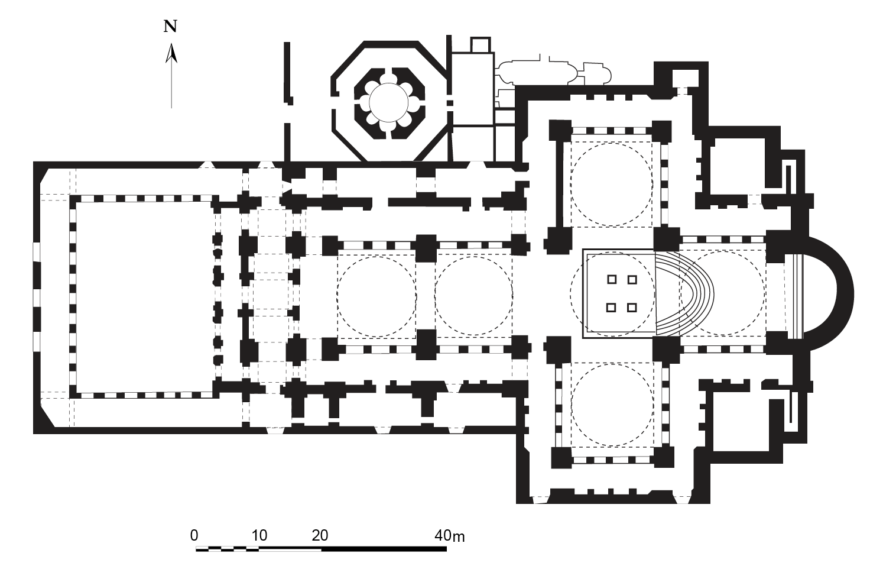

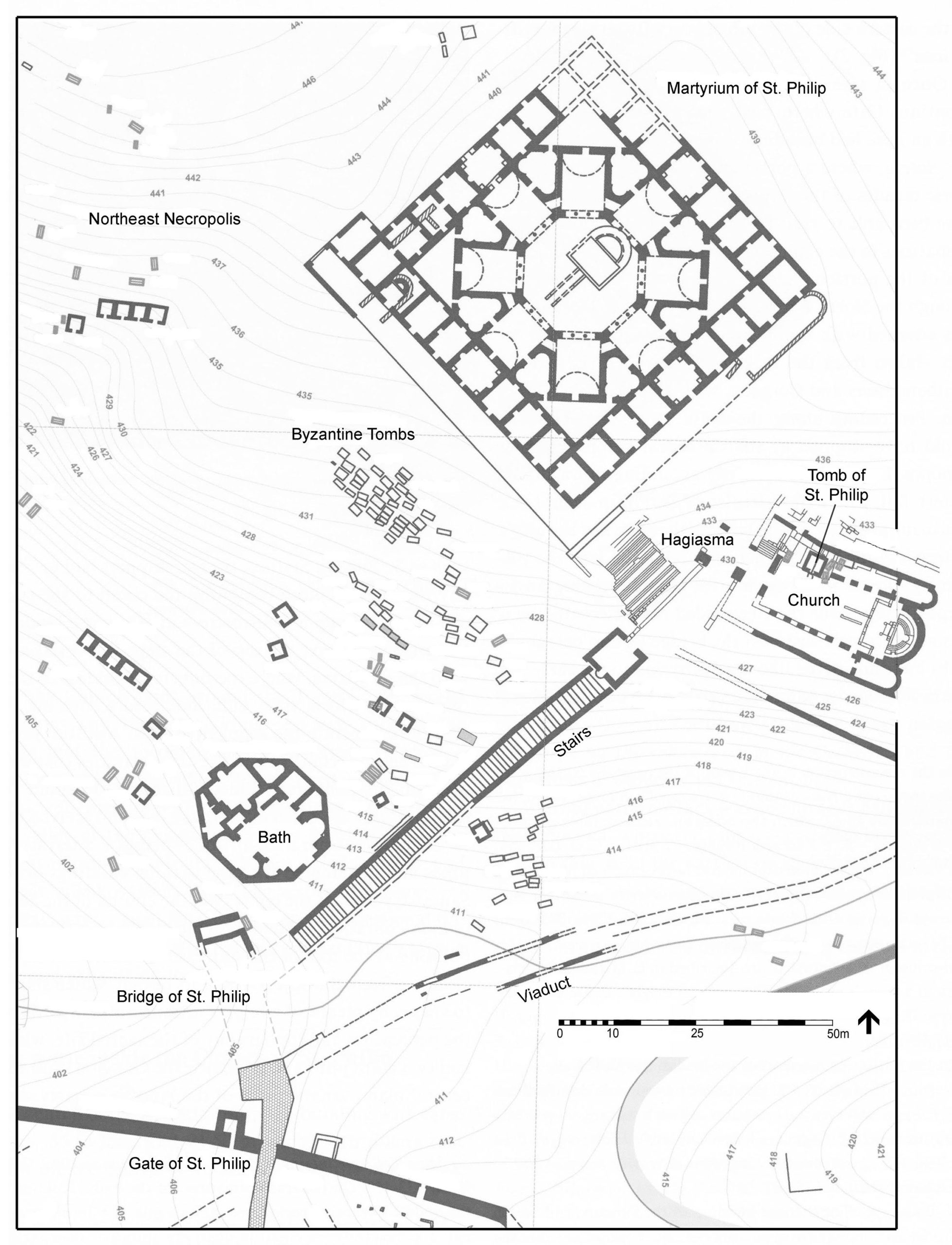

At Hierapolis in Asia Minor, a large octagonal complex was built at the site of the tomb of St. Philip (see plan below).

At Ephesus, a cruciform church arose at the tomb of St. John the Evangelist.

*

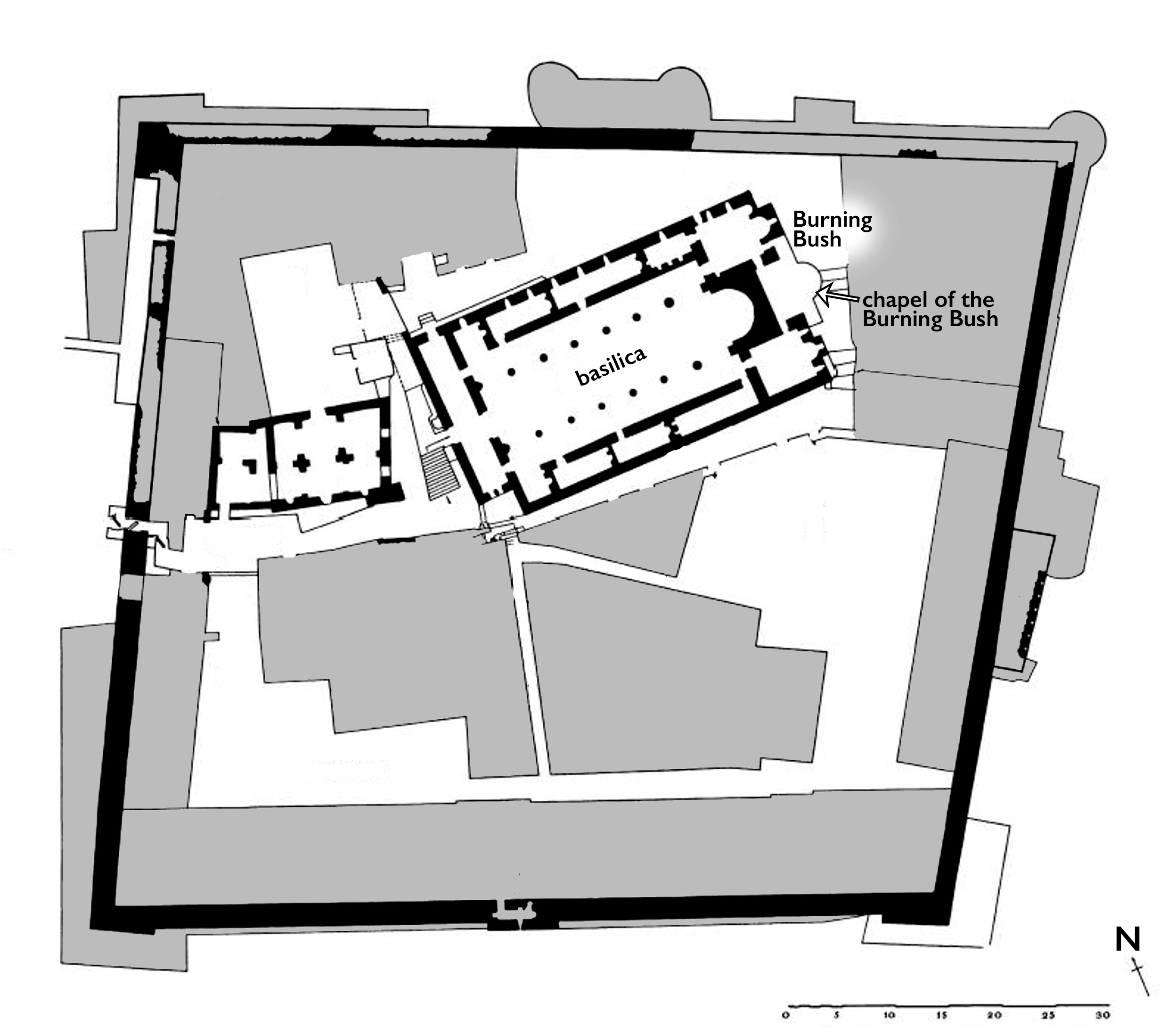

Others were simpler in form. At the martyrium of St. Thekla at Meryemlik, c. 480, a three-aisled basilica was added above her holy cave. At Sinai, the sixth-century basilica was augmented by subsidiary chapels along its sides, but the holy site—the Burning Bush, believed to be the bush through which God revealed himself to Moses Exodus 3:1–5—lay outside, immediately to the east of its apse (see plan below).

*

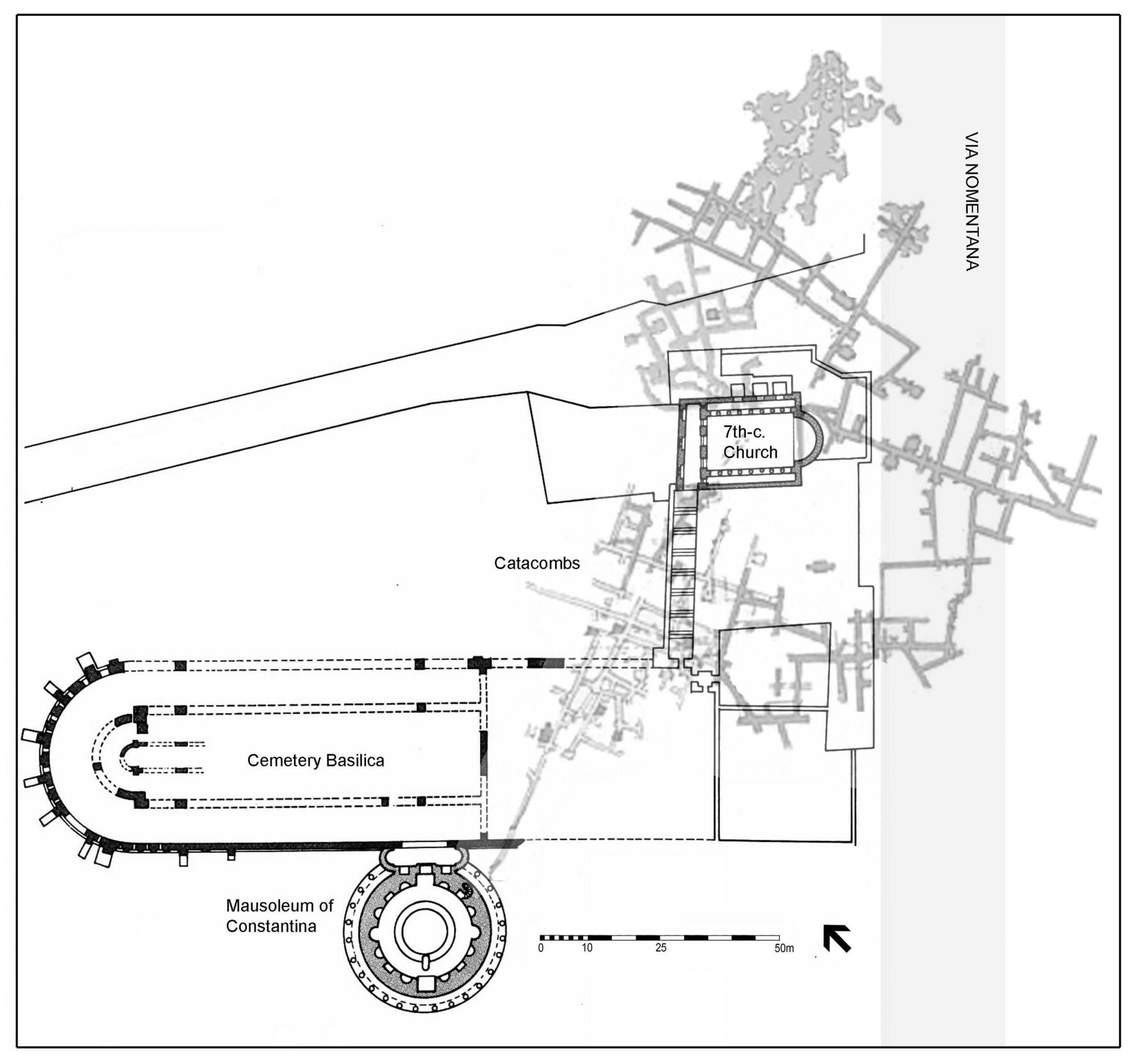

The desire for privileged burial perpetuated the tradition of Late Antique mausolea, which were often octagonal or centrally planned. In Rome the fourth-century mausolea of Helena (mother of emperor Constantine) and Constantina (the daughter of emperor Constantine) were attached to cemetery basilicas.

*

Cruciform chapels seem to be a new creation, with a shape that derived its meaning from the life-giving Cross, a relationship emphasized in the well-preserved Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, built c. 425, in Ravenna, which was originally attached to a cruciform church dedicated to S. Croce.

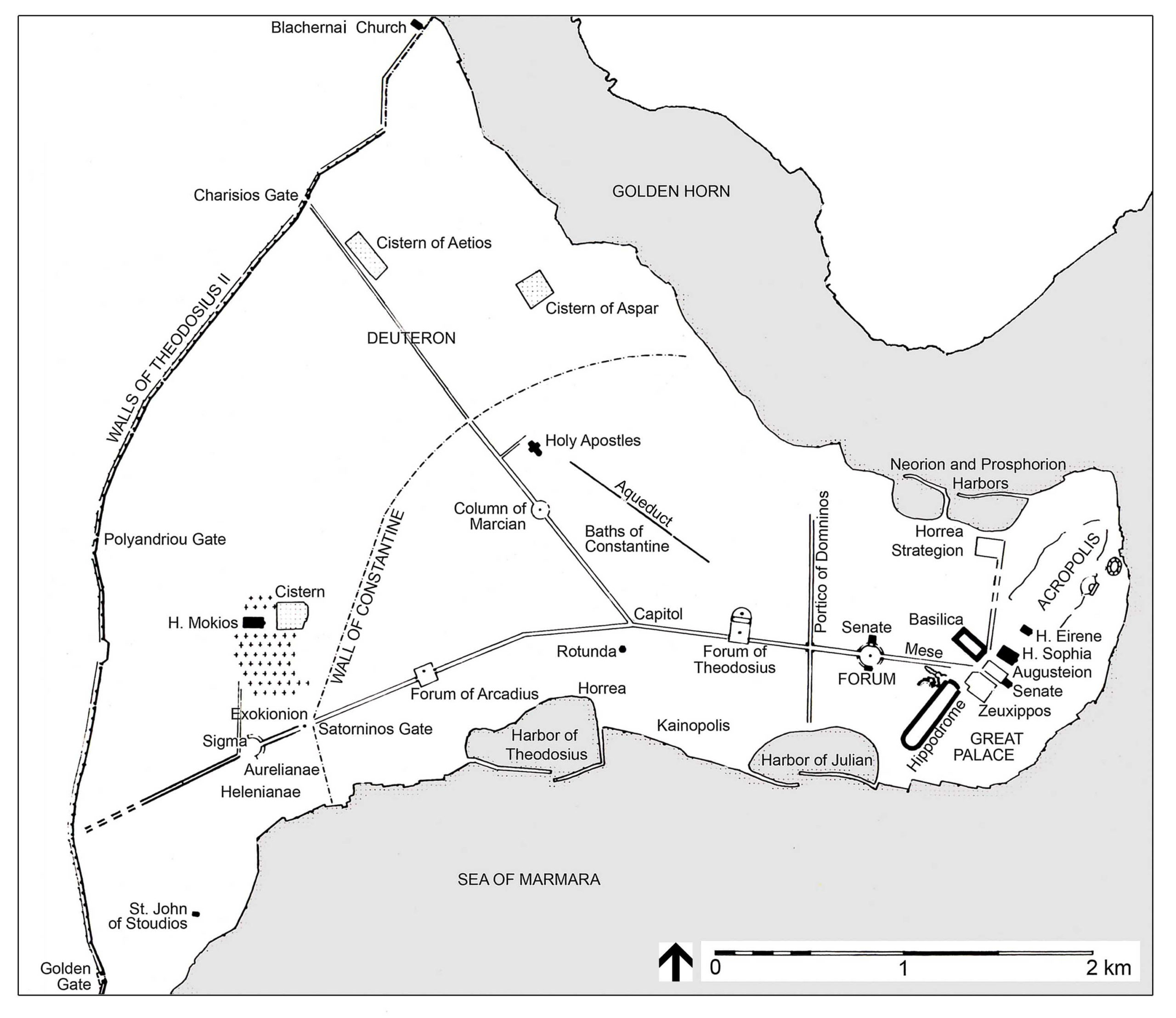

In Constantinople, the successors of Constantine were buried in the rotunda at the church of the Holy Apostles or its dependencies.

Monasticism

Monasticism began to play an increasingly important role in society, but from the perspective of architecture, early monasteries lacked systematic planning and were dependent on site-specific conditions. The coenobitical system (communal monasticism) included living quarters, with cells for the monks, as well as a refectory for common dining and a church or chapel for common worship. Evidence is preserved in the desert communities of Egypt and Palestine. At the Red Monastery at Sohag, the formal spaces are contained within a fortress-like complex, although it is unclear where with or without the enclosure the monks actually lived. In the Judean Desert, a variety of hermits’ cells are preserved—simple caves carved into the rough landscape.

Urban Planning

In general, urban planning in this period follows Roman and Hellenistic models, as Justinian’s new city of Iustiniana Prima (Caracin Grad, in modern Serbia) amply demonstrates.

In Jerusalem and Athens, there may have been an intentional visual juxtaposition of the new Christian cathedral with the abandoned Jewish or pagan temple. While the Theodosian Code (a collection of Roman law issued in 438 by Theodosius II and Valentinian III) legislated the cessation of pagan worship, it recommended the preservation of the temple building and its contents because of their artistic value. The transformation of temples into churches was rare before the sixth century.

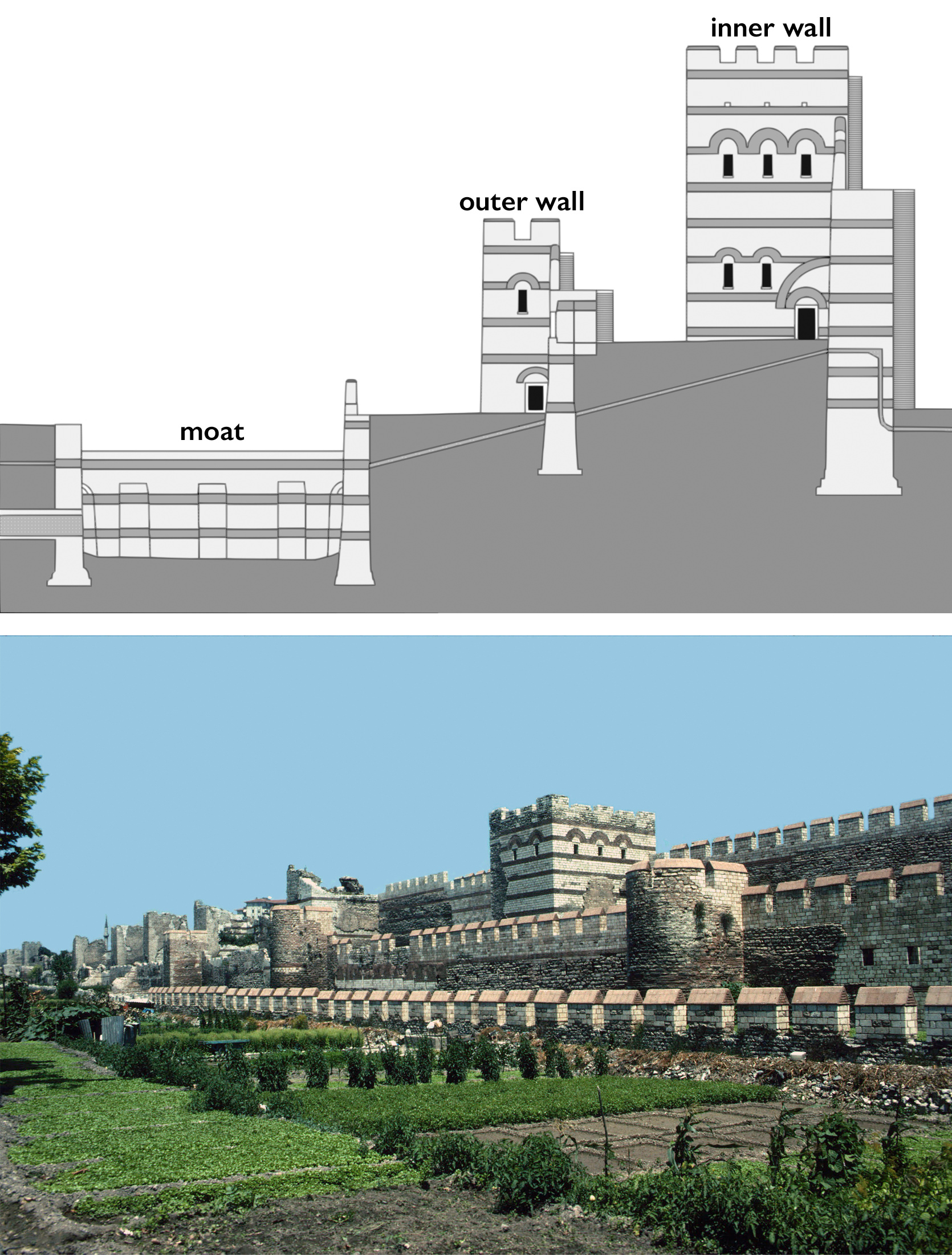

Defensive architecture followed Roman practices.

The walls of Constantinople, added by Theodosius II (412–13) stand as a singular achievement, combining two lines of defensive walls with a moat. In a like manner, the system of aqueducts and cisterns at Constantinople expanded upon established Roman technology to create the most extensive water system in Antiquity (see diagram below).

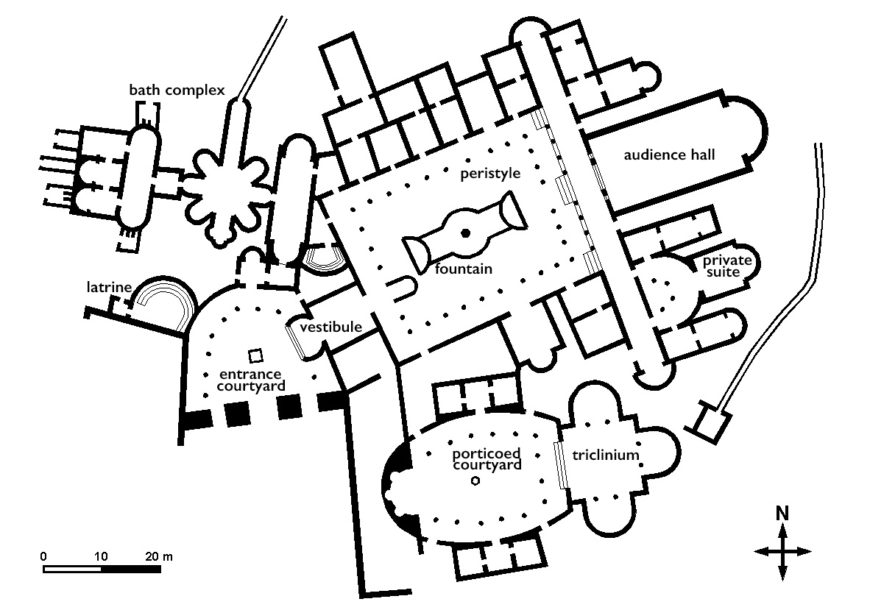

Domestic Architecture

Standard planning continued in domestic architecture as well. Large houses excavated in Asia Minor (Sardis, Ephesus), North Africa (Carthage, Spaitla, Apollonia), Italy (Ravenna, Piazza Armerina), Greece (Athens, Argos), and elsewhere include porticoed gardens, audience halls, and triclinia (dining rooms). The Great Palace in Constantinople and the so-called Palace of Theodoric in Ravenna were essentially elaborations on or repetitions of the Late Roman villa. Perhaps the most significant changes in the Late Antique domus (house) were the increasing size and number of ceremonial spaces (audience halls and triclinia)—as at the early fourth century villa at Piazza Armerina (in Sicily)—and the incorporation of chapels into the domestic setting—as at the Palace of the Dux at Apollonia (in modern Libya). The latter phenomenon is indicative of the growing importance of private worship and was a source of growing concern in ecclesiastical legislation. With significant economic and social changes, however, by the end of the period under discussion, the domus disappeared.

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)