48

A conversation

Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey.

Steven: We think of Hagia Sophia as a Byzantine church but it also has this whole other life after the invasion of the Ottoman Turks.

Elizabeth: We tend to forget about that. We tend to focus on this amazing Byzantine building and we forget about its afterlife and history from 1453 until the establishment of the Turkish Republic when it became a museum.

Steven: Buildings are living things and they accrue meaning and they change as societies around them change. This is just such a stark example.

Elizabeth: Because it was the most important Byzantine church it was an obvious thing for conversion. Because mosques and churches are spaces for congregations changing a few key things allow you to re-purpose the building almost immediately.

Steven: Constantinople was the primary city in the Byzantine East. It seems this treasure and within the city, the real jewel was this church.

Elizabeth: As the Byzantine Empire had been in financial decline and shrinking in terms of territory, this was one of the few things that got maintained and was still in good conditions where lots of other things in Constantinople weren’t in great shape when the Ottoman Turks took it in 1453.

Steven: I’ve read that the population had plummeted.

Elizabeth: Because of that a lot of the smaller church’s walls weren’t in great shape but this building still was. It was an obvious thing to convert and also it’s got a prime position. You can see it’s very close to the Bosphorus [Strait] and it’s also where a lot of key buildings, later on, are going to be built by the Ottoman Turks. It’s unsurprising that this was the first thing that was adapted and modified.

Steven: Because it was adapted and because it was turned from an orthodox church into a mosque, it survived.

Elizabeth: It becomes a symbol of authority because if this was the symbol of the Byzantine Empire’s religious authority and the emperor’s authority, then by converting it — having it become a mosque — is a symbol of the sultan’s power in the city and throughout the empire. It has a huge symbolic quality of sovereignty.

Steven: What evidence do we have of that conversion?

Elizabeth: The most obvious things are the covering up of the mosaics. They removed some of the later paint and plastering; you can see them.

Steven: The mosaics were covered up not because the Muslims don’t recognize Christ as at least a prophet but because of the prohibition of figural imagery especially within a religious space.

Elizabeth: Certainly that and also Christ, when he is depicted, he’s not depicted as Christ — he’s Jesus, and he’s a prophet. He doesn’t appear with Mary. He doesn’t appear as Christ Pantocrator, which is this very typical image in Eastern Orthodox churches. You can’t have him being shown in those ways because those are very Christian depictions of Jesus.

Steven: While we may not have figural images, we certainly have lots of symbols.

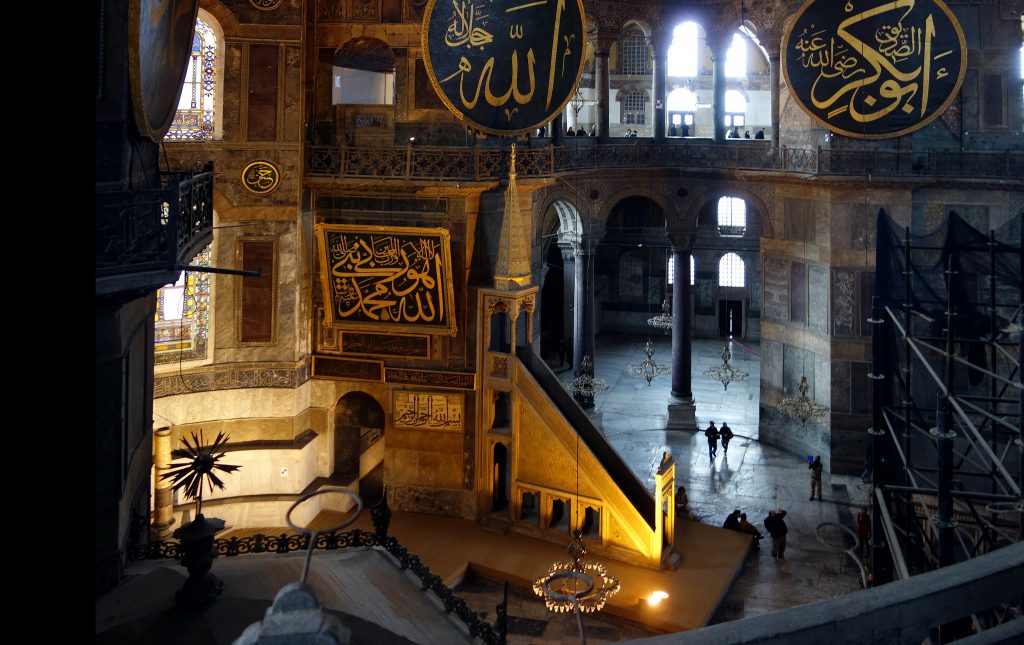

Elizabeth: Probably the most obvious thing when you come in are the enormous bits of Arabic calligraphy.

Elizabeth: Calligraphy is perhaps the most important Islamic art. Arabic in the word is critical to the foundation of Islam because the belief is that Muhammad recited the words of God as told to him directly. Arabic is very important. What’s interesting to me is that a lot of these roundels — which were later additions — are in Arabic, so a lot of the community couldn’t read them.

Steven: Even though they were Muslim this still would have been a foreign language.

Elizabeth: Of course, because they spoke Turkish. When you walk into Hagia Sophia, you walk in and you proceed towards the apse and everything looks normal until you notice that the mihrab is off-center.

Steven: The mihrab is the niche at the far end of the building that is a way of pointing towards Mecca.

Elizabeth: It’s really the important thing because it has to tell you which direction you’re supposed to pray. The thing is, it’s off-center here, because that’s the direction of Mecca.

Steven: In fact, I noticed that not only is the mihrab off-center, but all of the architectural elements that incase it—that is the platform on which it’s placed and the staircase to the right, or minbar—are all oriented together, but in opposition to the church that surrounds it.

Elizabeth: You don’t notice it unless you’re really paying attention. We also have the platform for the muezzin to make the call to prayer within the mosque, and then we also have the Sultan’s Lodge, all of which are oriented more towards the south than east — the way the building is oriented. You can have these interior additions that reorient the space in a very powerful way.

Steven: I want to go back to the Sultan’s Lodge because it’s just magnificent.

Elizabeth: It’s gorgeous. The sultan held a very special position. He’s the political authority but around him developed a cult of personality. He was viewed as being divinely appointed. His person is sacred and there were very strict protocols that developed in terms of who could talk to him. In many ways, later on in the Ottoman Empire, he gets very isolated, but this is how he would come and worship: he has his own entrance and then he has his own elaborate procession way in. There’s a whole balcony that he would be able to walk into. Everyone could see him but no one could touch him. Also, it’s elevated. It’s not on the same level. He’s on a different plain above.

Steven: Then probably the most obvious addition are the incredible minarets outside…

Elizabeth: …these four very tall, thin pencil minarets. Pencil minarets and domes are what everyone comes to associate with Ottoman architecture. They’re the quintessential features of mosque architecture but also of the Ottoman urban landscape.

Steven: By pencil minaret, you’re distinguishing them from the thicker minarets that you see maybe in Egypt. The purpose of the minaret was as a high place to call the faithful to prayer.

Elizabeth: In some sense it’s very functional. The muezzin goes up and he calls everyone to prayer. It’s a much better position for doing that than on the ground. Your voice can travel much further. Today we can see the speakers, the megaphones.

Steven: They woke me up this morning.

Elizabeth: They also provide you with a great opportunity to define your skyline. By building in a distinctive style it asserts who you are and what your identity is but it also helps all of us today who are looking at these buildings go, “pencil minarets must be Ottomans.” It’s a really clear distin- guishing feature because you don’t get them in Central Asia, you don’t get them in Iran. You really only get them where the Ottoman Empire had a presence. There are two earlier ones. One built by Mahmed II and then one by Sinan, the famous architect who built many of the great monuments in Istanbul in the Ottoman Empire. Then we have two more that were added by Murad III, a sultan from the late sixteenth century. The number of minarets you have is significant. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque or the Blue Mosque, which is right opposite Hagia Sophia, has six, which was a bit of a controversy when it was built because that’s the number Mecca had.

Steven: The Blue Mosque is such a great example of the kind of impact that Hagia Sophia as a mosque had on the architecture throughout the city.

Elizabeth: You can’t underestimate the importance of Hagia Sophia both in terms of the use of domes and its plan, and as we go and look at other mosques and as you look at different Ottoman creations, here you’ll start to see that no matter how much there is innovation — and there is huge innovation — Hagia Sophia is always somewhere lurking in the back of an architect’s mind.

Steven: I can see why.

Watch the video

<https://youtu.be/r6383ZDXB0Q>.