28

The British Library

Kathleen Maxwell

Of the estimated 60,000 surviving Greek manuscripts, approximately 5,400 contain Gospel texts. The popularity of the Gospels is explained by their central role in the liturgy of the Orthodox Church which required a lection (excerpt) from one of the Gospels. On special feasts such as Good Friday, more than a dozen lections would be read throughout the day. Thus, Greek Gospel manuscripts can be divided into two types:

- There are more than 2,930 continuous text Gospel manuscripts; these contain the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, and are usually formatted with one column of text

- Gospel lectionaries, on the other hand, comprise more than 2,450 additional manuscripts. These texts include excerpted Gospel readings arranged according to the liturgical calendar of the Orthodox Church which begins on Easter Sunday with John’s Gospel (John 1. 1–17).

Lectionaries often have two text columns, presumably because they would be easier to read aloud. Many continuous text Greek Gospel books were adapted to function as Gospel lectionaries, so it is important to know something about both types of manuscripts. This article focuses on a small selection of illuminated manuscripts drawn from over 200 Greek Gospel books in the collection of the British Library.

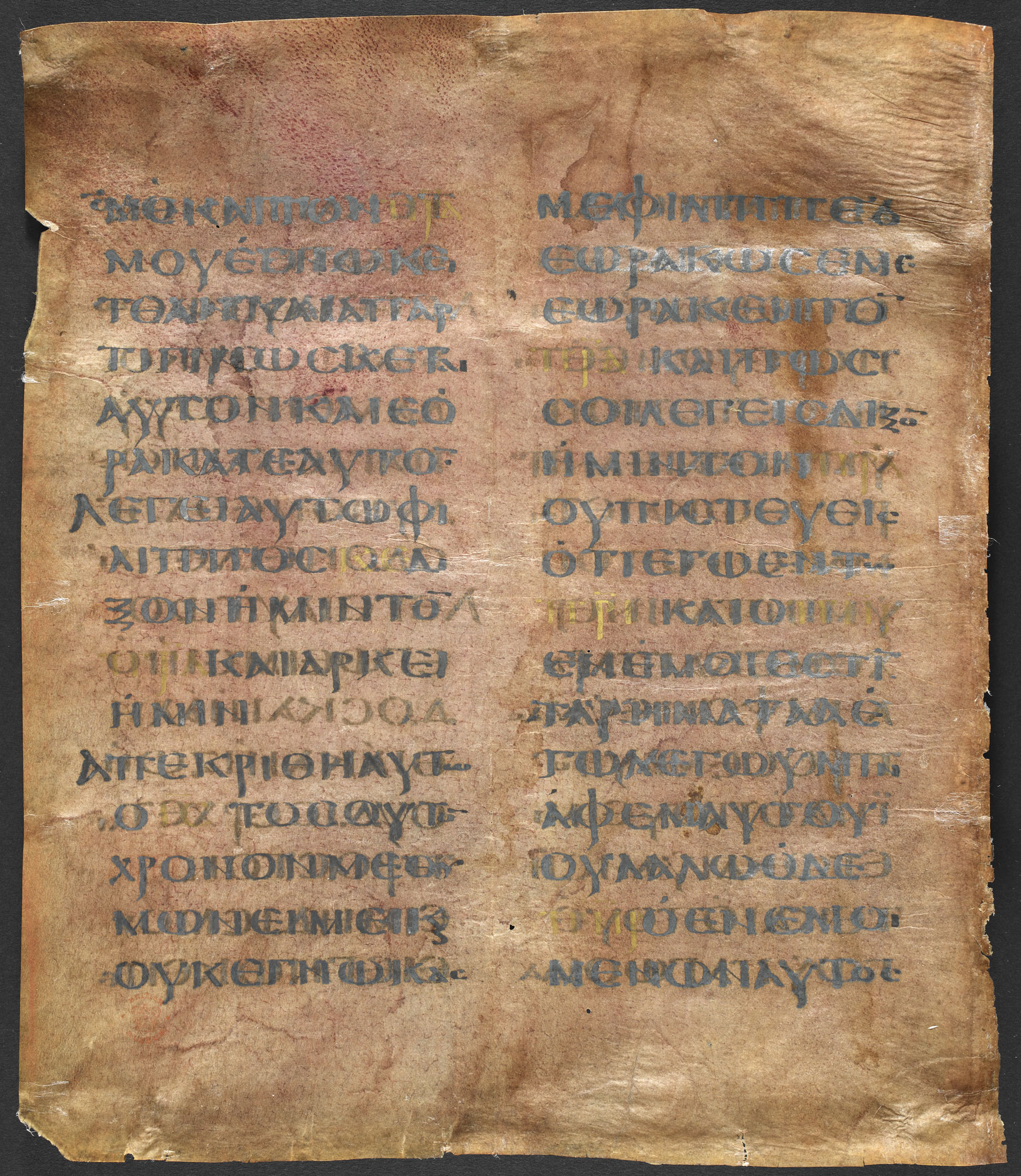

Art historians study Gospel texts that feature figural and/or non-figural decoration. While images inspired by the four Gospels can be found in many media before the 6th century, the earliest extant Greek Gospel manuscripts with figural imagery are from the 6th century and are likely the product of an imperial scriptorium in Constantinople. They are the Rossano Gospels (now in Rossano, Italy) and the Sinope Gospels (now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris).

Both Gospels are incomplete, but feature gold or silver writing on purple parchment. These features taken together with their splendid narrative miniatures suggest a patron of the highest standing, possibly a Byzantine emperor or a member of the royal family.

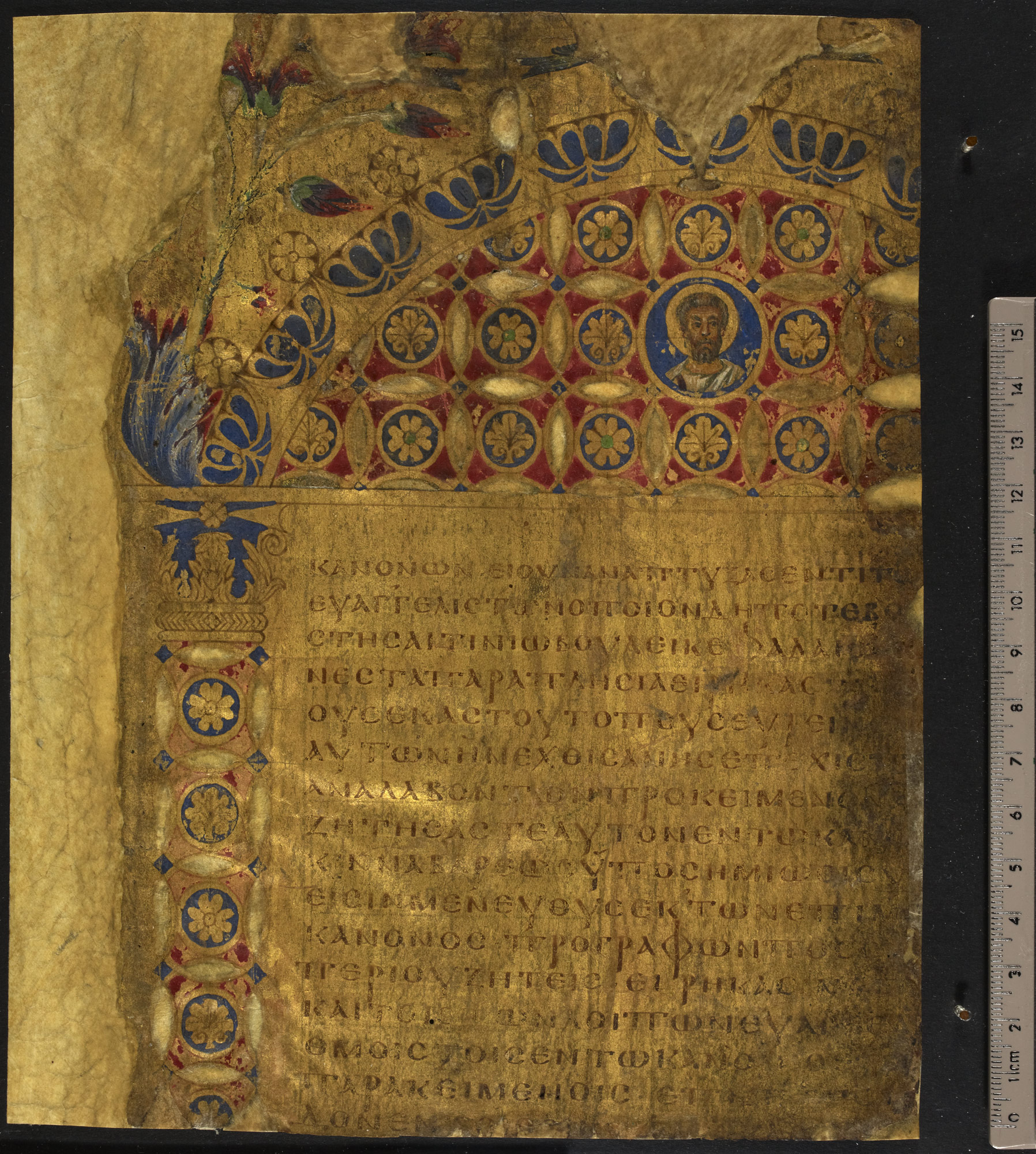

Our contemporary chapter and verse system of referencing the Gospels was not perfected until the mid-16th century, and for this reason, many Greek Gospel manuscripts contain aids for readers that are not found in our contemporary New Testament texts. Readers were dependent on a reference system initiated by Ammonius (3rd century) and refined by Eusebius of Caesarea (263–339). Ammonius numbered sections of the Gospels to make it easy to find important passages. These numbers are typically found in the margin near the appropriate Gospel passage. Eusebius then created a series of 10 Canon Tables in which these Ammonian section numbers were organized so that the reader could easily discover parallel passages in the other Gospels. The first Canon table included four columns labeled Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. In Matthew’s column all of the Ammonian section numbers for passages that are found in all four Gospels would be listed. The columns for the other three evangelists would include their corresponding section number for the relevant passage in Matthew in the first column. Canon Tables are included at the beginning of many Greek Gospel books and they are often prefaced by a letter written by Eusebius explaining their function.

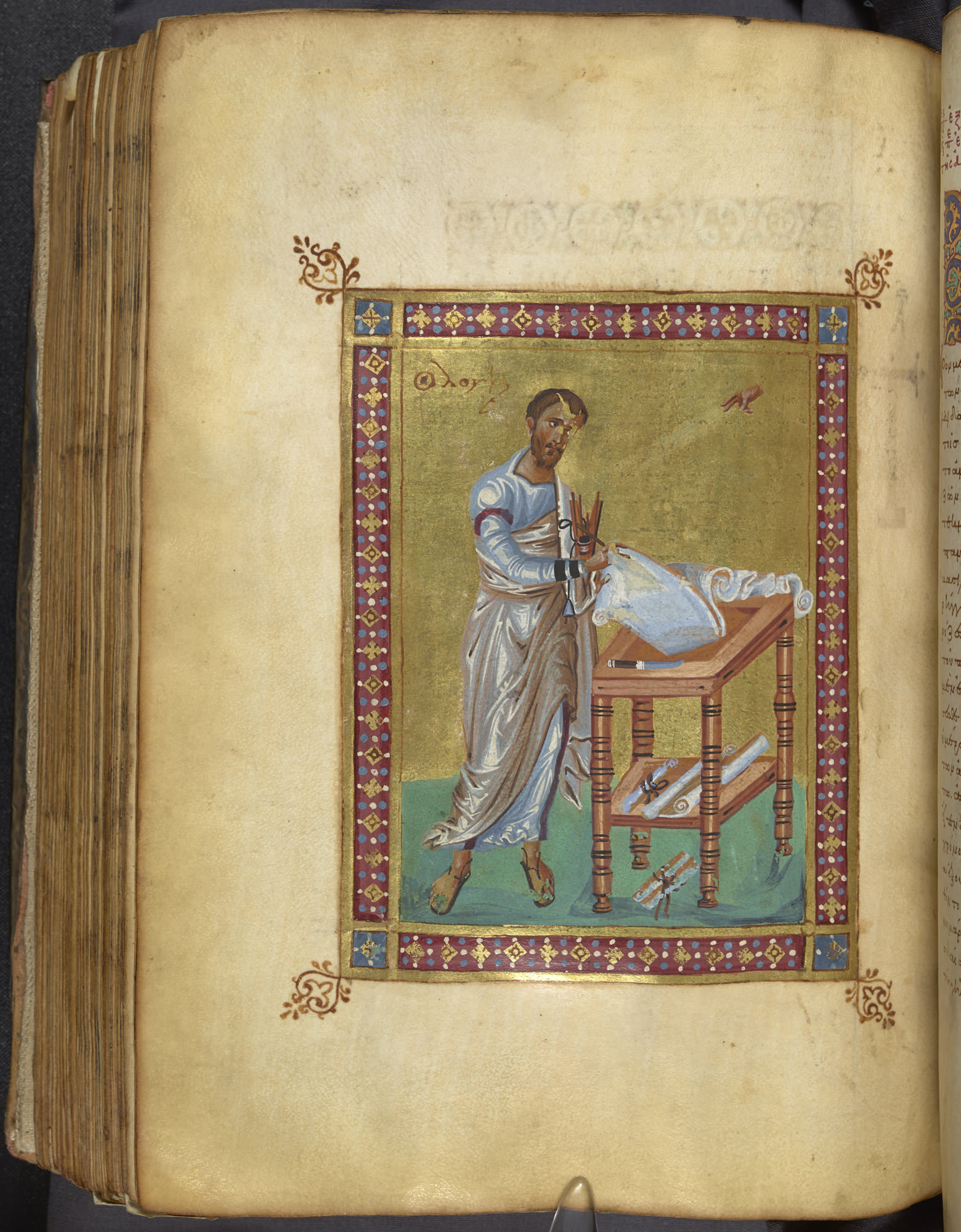

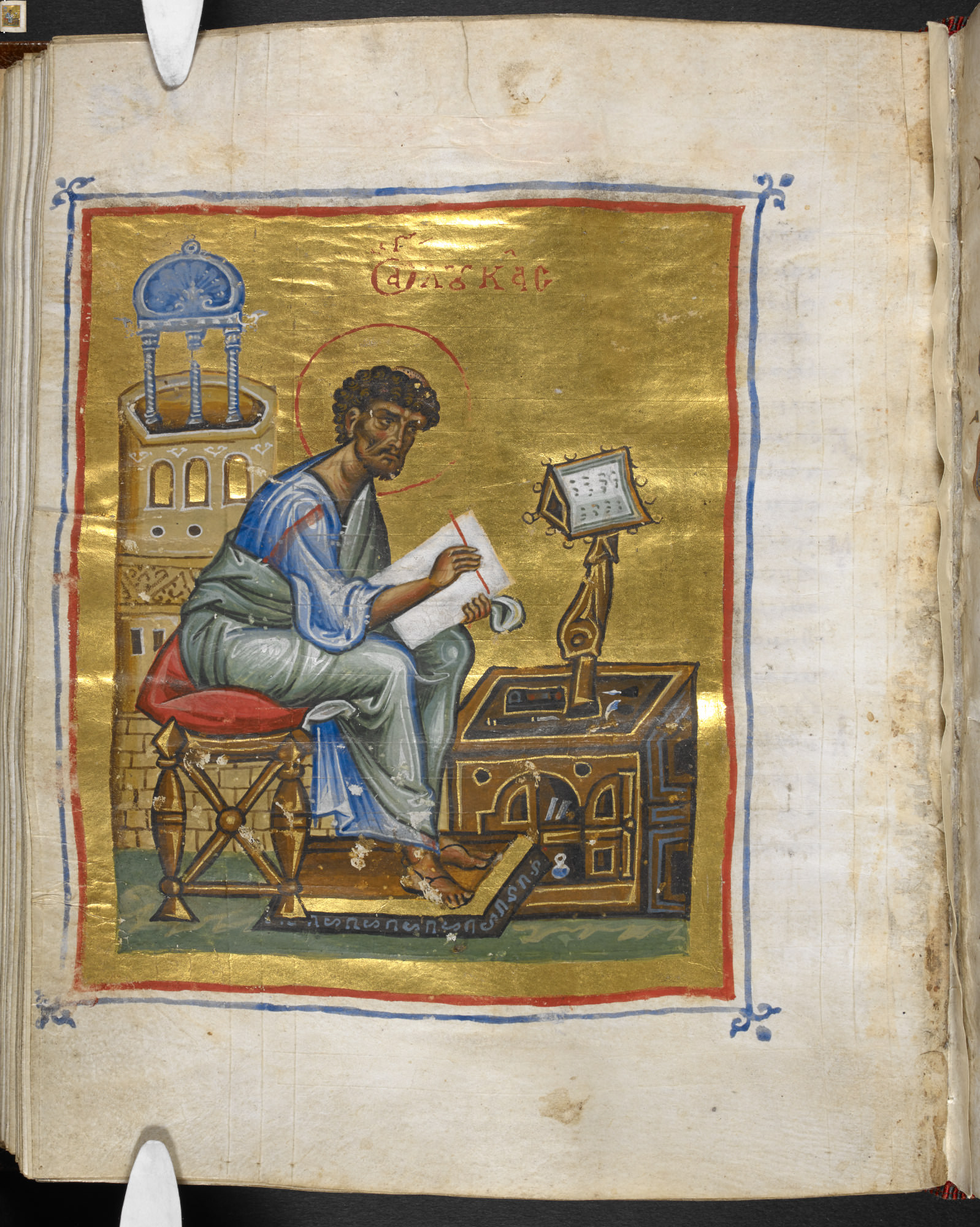

Moreover, a surprisingly high number of Gospel books also include framed portraits of the evangelists at the beginning of their respective Gospels. The evangelists are generally shown seated and writing at desks against gold backgrounds. On the page opposite to the depictions of the Evangelists, framing the title at the beginning of their respective Gospel was a decorated headpiece that often complemented the color scheme of the evangelist and/or his frame. These features, combined with decorated Canon Tables at the beginning of the manuscript, required a trained illuminator. The golden color of the Canon Tables, backgrounds of the evangelist portraits, decorated headpieces at the beginning of each Gospel, various titles, as well as any decorated initials, added significantly to the cost. Such manuscripts were reserved for the elite.

Figural and non-figural decoration also had a functional role in Greek manuscripts. If we remember that foliation/pagination and therefore tables of contents and indices were virtually nonexistent, we can begin to appreciate the visual cues provided by evangelist portraits and headpieces in these manuscripts. Such cues assisted the reader in locating the beginnings of each of the four Gospels. The pinpointing of specific passages within each Gospel would be aided by the presence of the Ammonian section numbers, assuming, that is, that the reader knew the section number of the desired passage, for no index to these section numbers was included in these manuscripts. The Ammonian section numbers in the margins were often paired with their relevant Canon Table number so that the reader could consult that table and immediately determine if other Gospels contained parallel passages.

Another aid to the reader was included in many, but not all Gospel books. These were the numbered chapters (kephalaia) and their descriptive titles often listed at the beginning of each Gospel (usually in the folios directly before the evangelist portrait). Individual chapter titles would be repeated in the top margin of the folio where the beginning of the chapter was found. While the chapter titles would at least inform the reader of the subject of their respective text, they were relatively few in number and thus less effective in finding more obscure Gospel passages.

Some Greek Gospel books created in the late 9th and 10th century rank among the finest illuminated manuscripts ever produced during the Byzantine Empire. Add MS 28815/Egerton 3145, a large two-volume work including the entire New Testament, is an example. The distinctive standing portrait of Luke at the beginning of Acts (Add MS 28815, f. 162v) is one of the finest author portraits in a Byzantine manuscript. Luke’s painterly face contrasts with his ethereally-defined pastel-colored garments. The artist’s classicising approach to the drapery is further differentiated from the almost impressionistic rendering of the scroll which Luke holds unfurled on his desk. The seated portrait of Luke before his Gospel (fol. 76v) was likely executed by the same artist. Here, however, the expressive surface effects of the evangelist’s drapery compromise the integrity of the figure beneath and are reminiscent, at least in the mid-torso area, of melted frosting sliding off of a cake. The resulting instability is exacerbated by the overly ambitious design of Luke’s chair and the awkward angle of his footrest.

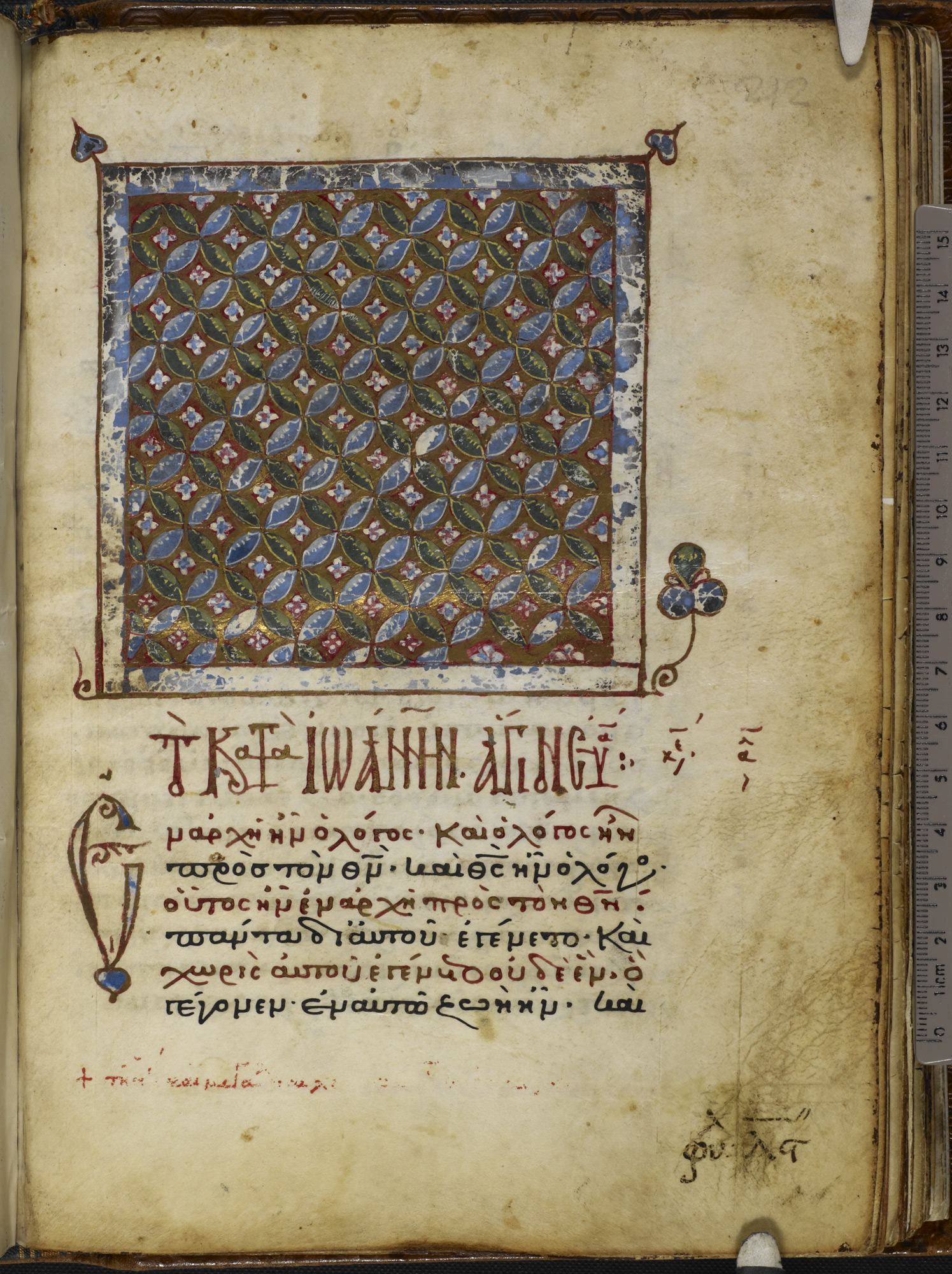

Burney MS 19 is a fine 10th-century Gospel book to which evangelist portraits were added in the first half of the 12th century. The evangelist portraits are striking examples of the so-called Kokkinobaphos Master, an artist or workshop that created high quality work in a number of manuscripts found in the period circa 1125–1150. The portraits in Burney MS 19 are in exceptional condition and feature highly animated facial expressions and beautiful pastel-colored garments. John’s headpiece (f. 166r), however, dates to the 10th century and is an example of the Byzantine-blossom style of ornament that was popular in Greek manuscripts throughout the 14th century.

Harley MS 1810 is an unusual Gospel manuscript in that it contains – in addition to Canon Tables, evangelist portraits and headpieces – 17 framed narrative miniatures within its Gospel texts. This 12th-century work is assigned to a large group of manuscripts that have been dubbed the ‘decorative style’ group. Comprising over 100 manuscripts, the majority of which are Gospel texts, the decorative style features bold evangelists in bright pastel hues and a distinctive deep black ‘low Epsilon script’. Some scholars assign decorative style manuscripts to Cyprus or Palestine while others are hesitant to assign this largest single group of Greek manuscripts to any place other than Constantinople. Like many Greek Gospel books, Harley MS 1810 was adapted for liturgical use, that is, to be used as a lectionary.

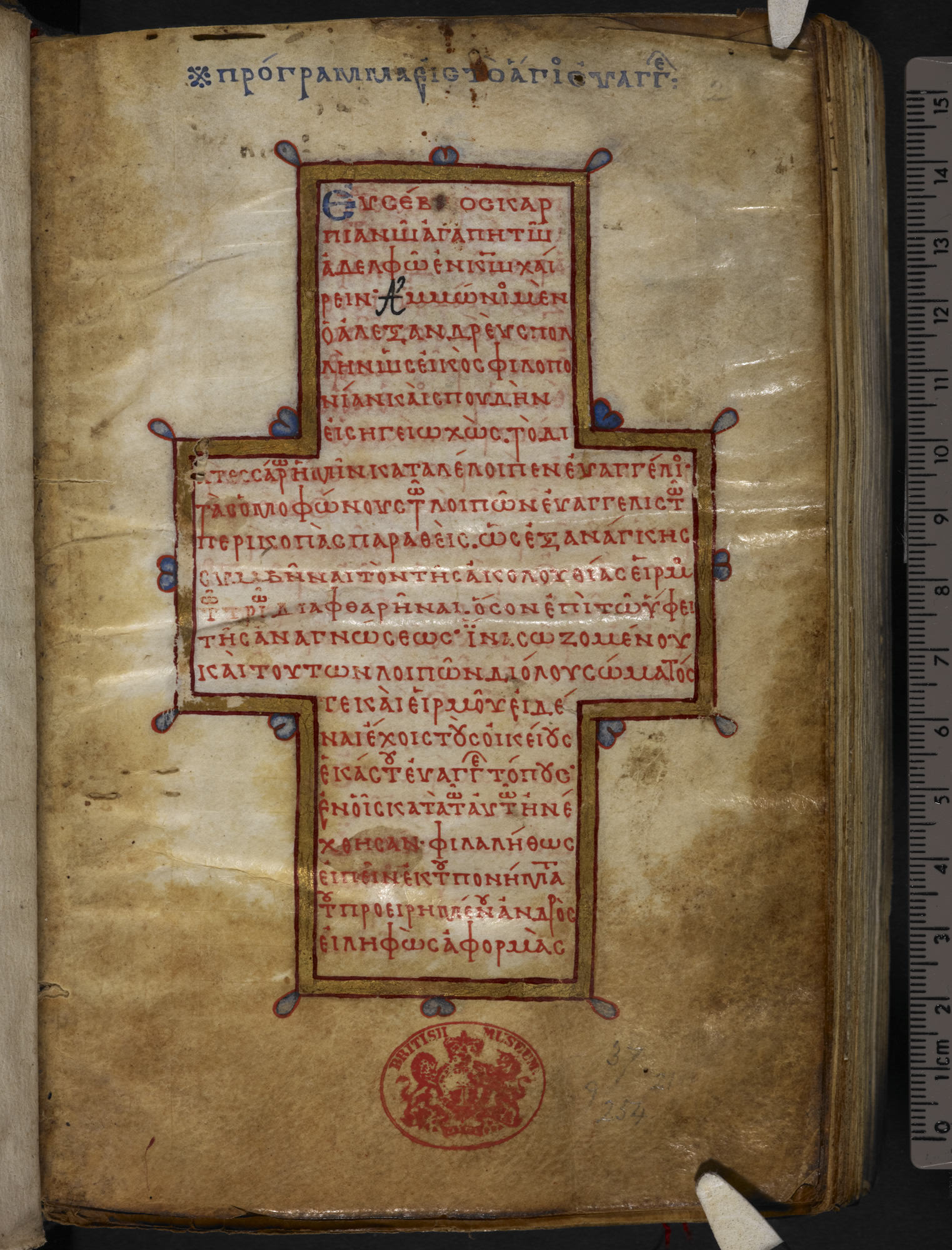

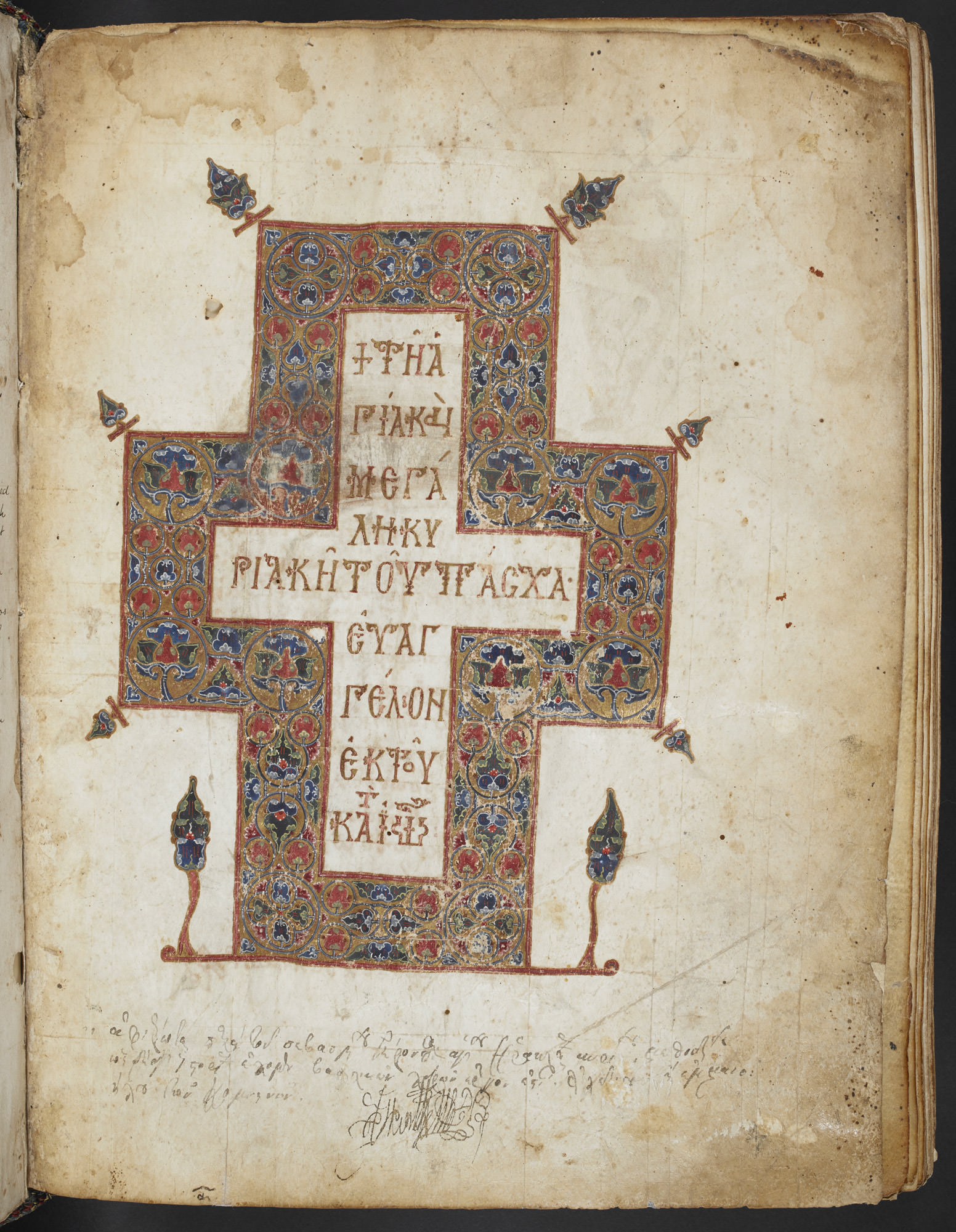

It is fitting to end our discussion with Add MS 39603, a spectacular Greek Gospel lectionary. This manuscript is comprised of Gospel texts arranged according to the readings of the liturgical year. The lectionary opens with the readings for the movable feasts, beginning with Easter Sunday. The first folio displays an extraordinary cross-shaped frame with a golden title announcing that the following reading is for Easter.

Even more remarkable, the entire text is written in a cross-shaped format with small decorative projections marking all eight corners of the text. The use of the cross-shaped text is highly unusual, for it ensures that the area for writing is not fully utilized and thus adds to the cost of the manuscript. It also makes it more difficult for the scribe to format his text. Only a few manuscripts in this format survive and they were likely commissioned by an imperial patron.

There are many more illuminated Greek Gospel manuscripts available to view in full on Digitized Manuscripts <https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts>.

References

J. Lowden, The Jaharis Gospel Lectionary: the Story of a Byzantine Book (New York, 2009).

T. S. Pattie, Manuscripts of the Bible: Greek Bibles in the British Library, revised edition (London, 1995).

A. Weyl Carr, Byzantine Manuscript Illumination 1150-1250 (Chicago, 1987).

Originally published by the British Library. <https://www.bl.uk/greek-manuscripts/articles/illuminated-byzantine-gospels#authorBlock1>