40

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

Constantinople reclaimed

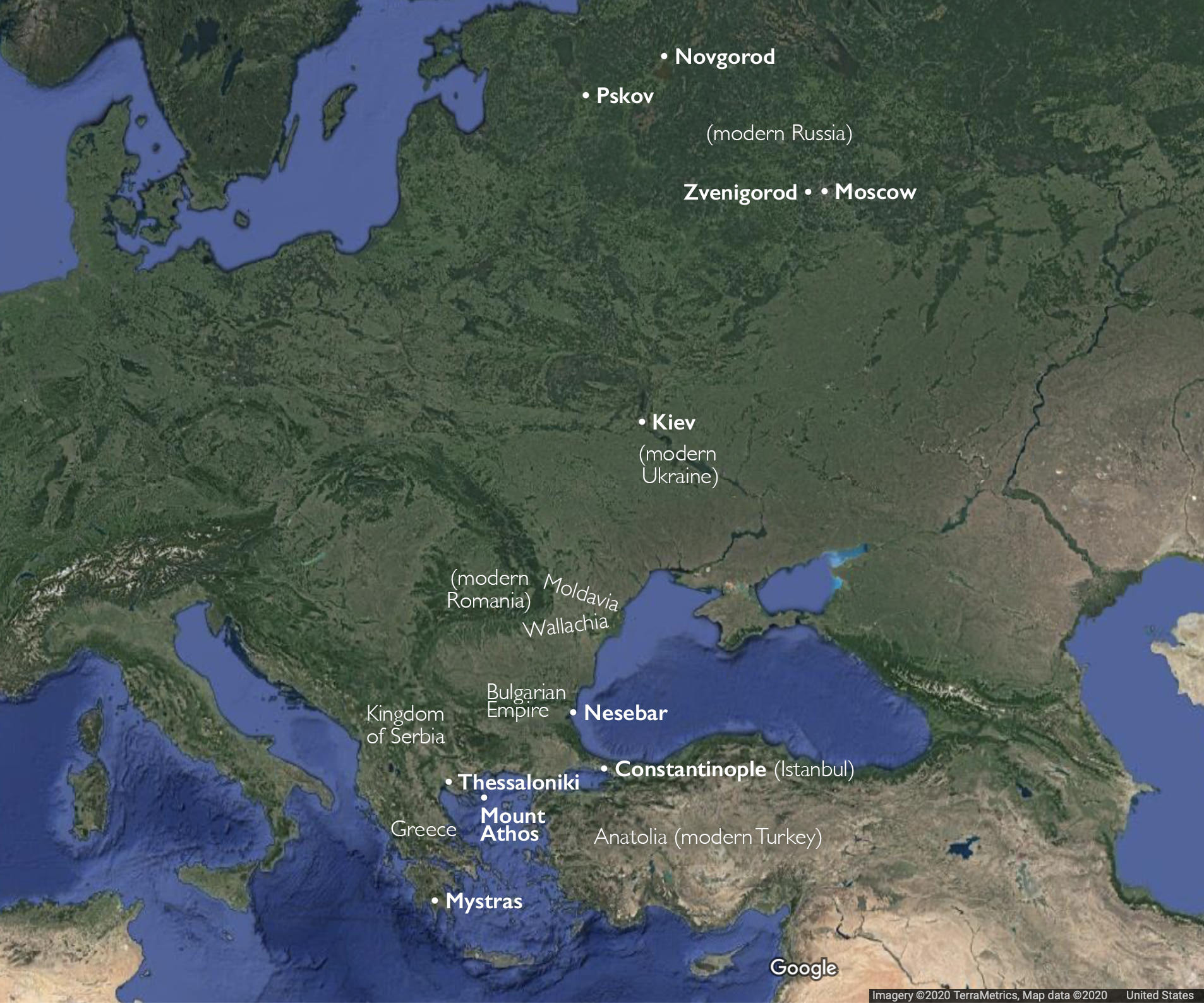

In 1204, crusaders of the Fourth Crusade sacked and occupied the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, beginning the period of the Latin Empire (the Byzantines referred to western Europeans faithful to the pope of Rome as “Latins” or “Franks”). But in 1261, the Empire of Nicaea, a Byzantine successor state, retook Constantinople and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos (reigned 1261–82) as their new emperor, ending the period of the Latin Empire.

The “Palaiologan Renaissance” in Constantinople

In Constantinople, church architecture was revived after the reconquest of the city in 1261. Most constructions represent additions to existing monastic churches, probably following the model of the triple church at the Pantokrator monastery.

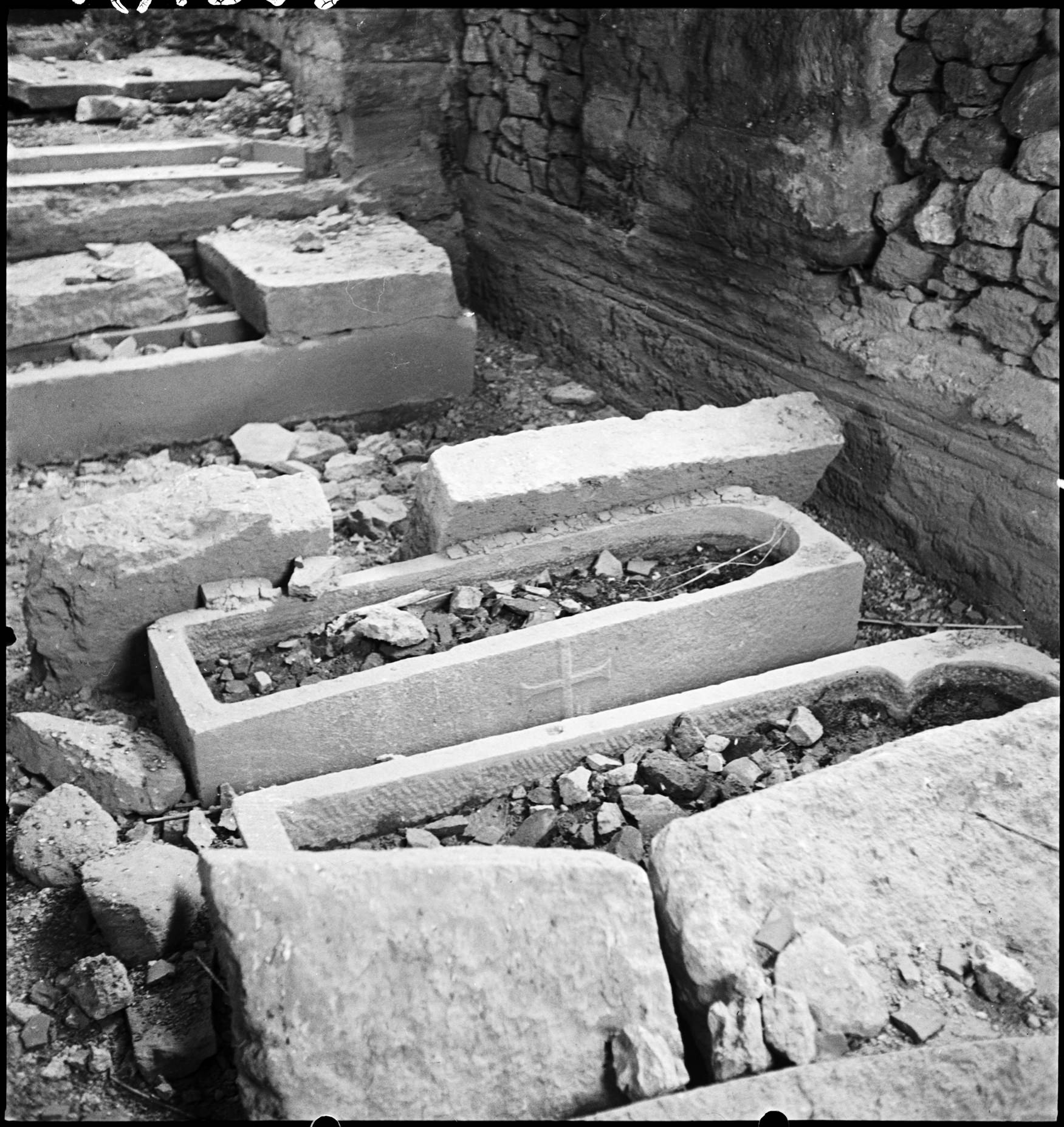

In all, there is little attempt at visual integration. An impressive funeral chapel as a setting for privileged burials was a standard feature, along with additional narthexes (the entry vestibules preceding the nave or naos of a Byzantine church) or ambulatories (a passage around a central space), equipped for burials. The building complexes are distinguished by an irregular row of apses (semicircular recesses) along the east façade, topped by an asymmetrical array of domes. The parts read individually, with a marked contrast between the Middle and Late Byzantine forms.

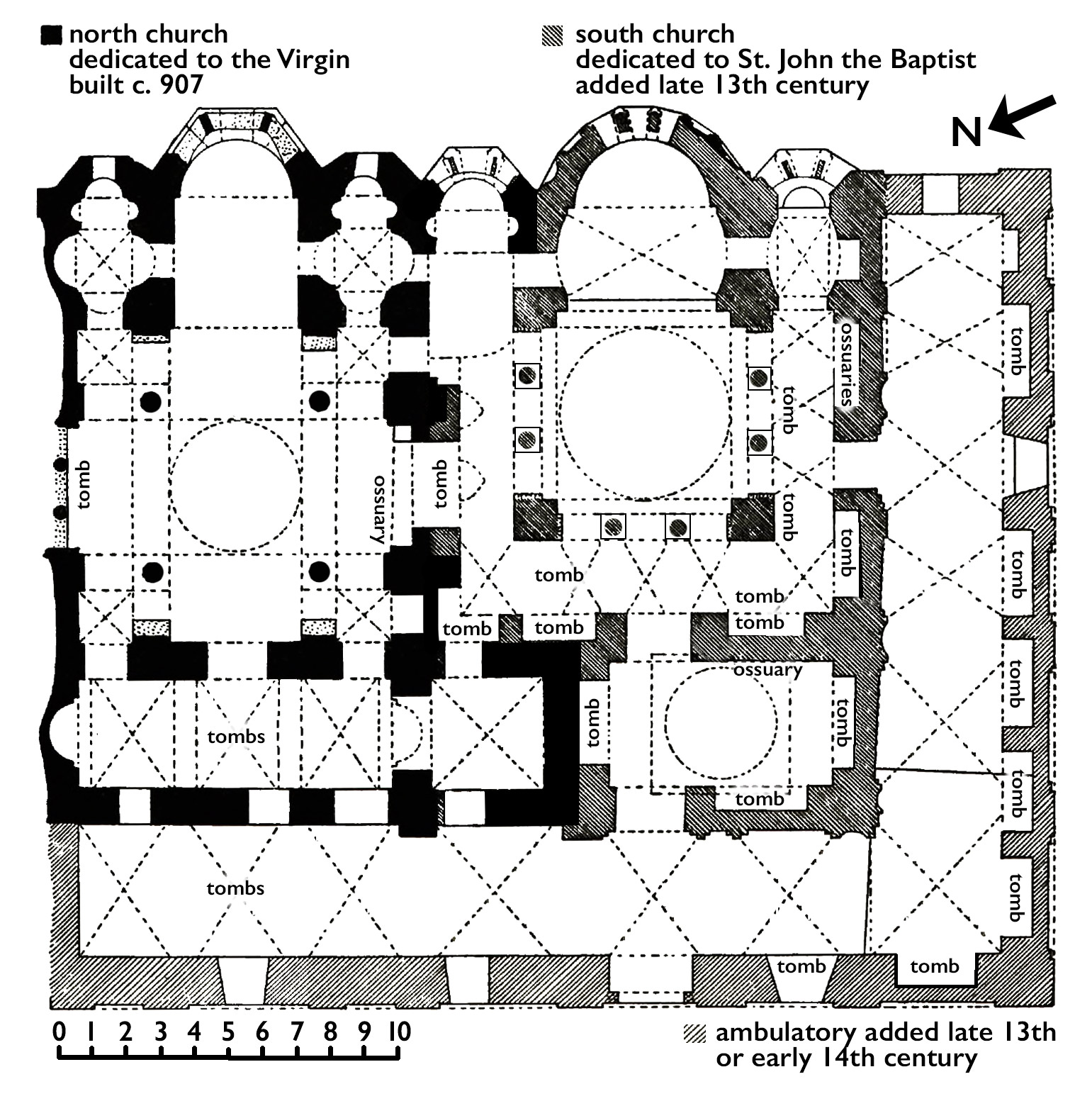

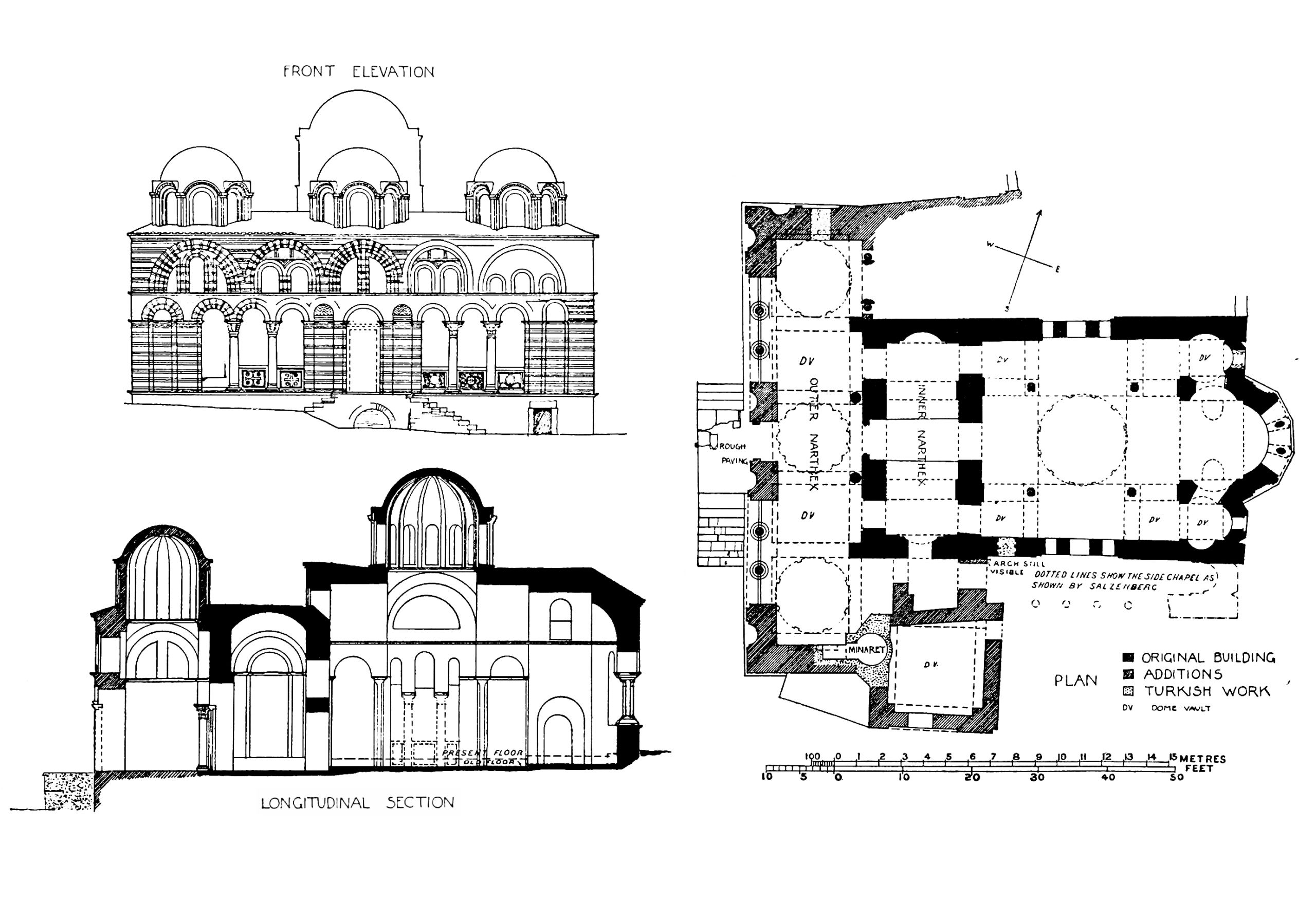

The Mone tou Libos

The monastic complex known as Mone tou Libos (first established c. 907), for which the typikon (a document outlining the organization, rules, and liturgical observances for a monastery) survives, was expanded c. 1282–1303 by the widow of Michael VIII with the addition of an ambulatory-planned church (a church with a central space enveloped by a curved aisle, or ambulatory) equipped with arcosolia (an arched burial niche), where the early members of the Palaiologos imperial family were buried.

In a second, closely related building campaign, an outer ambulatory was added along the south and west of the complex, with numerous additional arcosolia tombs.

*

*

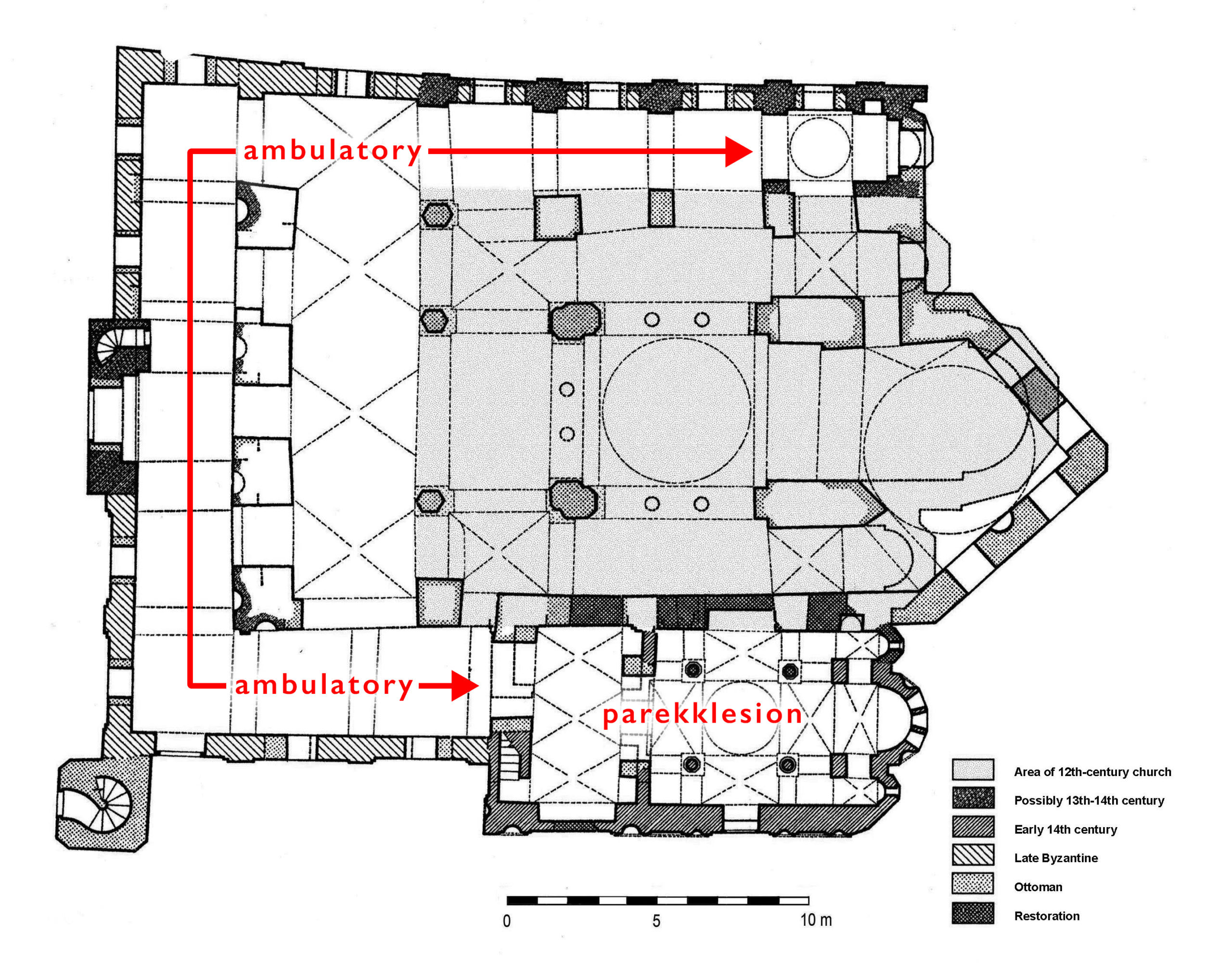

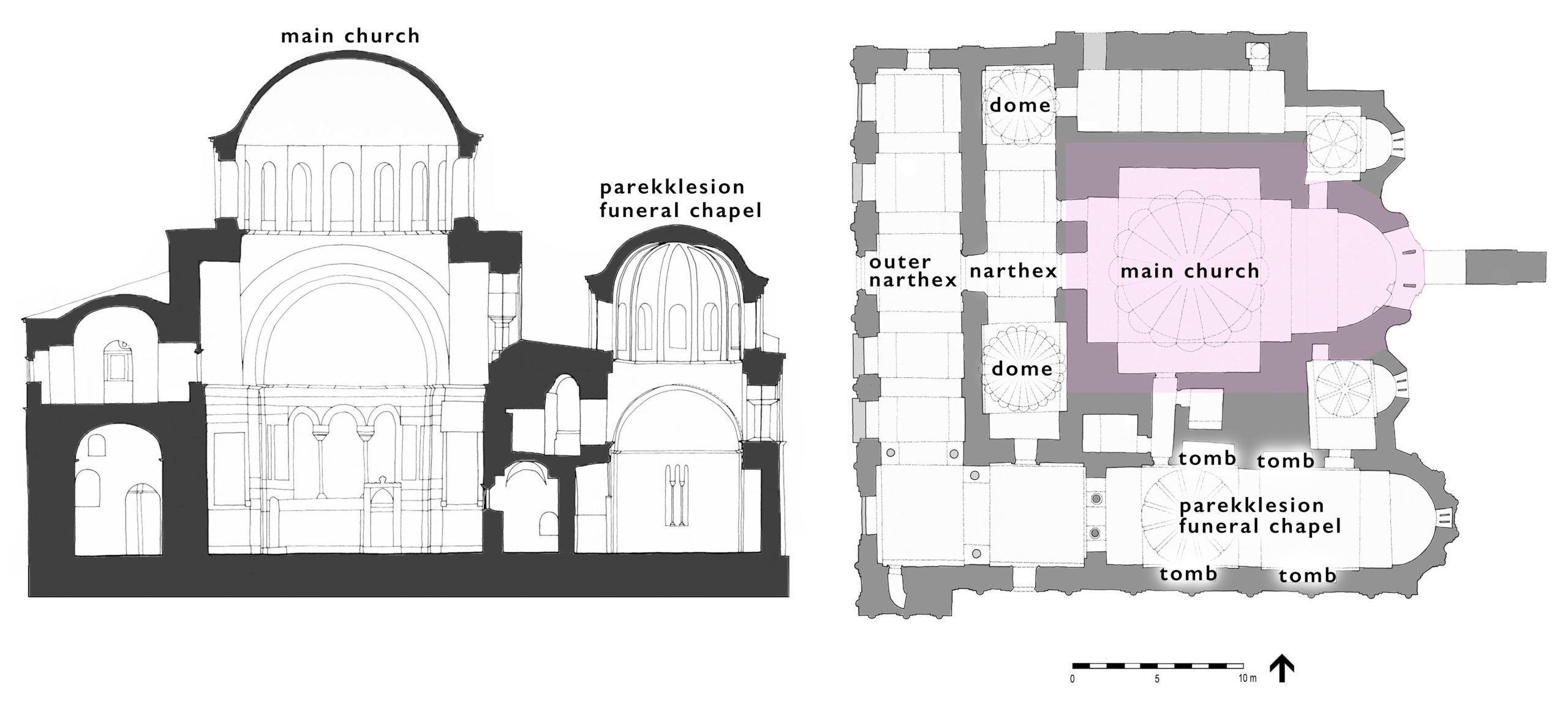

The Theotokos Pammakaristos

At the Theotokos Pammakaristos, a twelfth-century ambulatory-plan church was expanded in several stages, with chapels, a belfry, and an outer ambulatory. Most important is the south parekklesion (subsidiary chapel), a tiny but ornate cross-in-square chapel, built c. 1310 to house the tomb of Michael Glabas Tarchaniotes, a Byzantine aristocrat and general who lived c. 1235 to c. 1305–08. (A cross-in-square church is a church with a square naos and a central dome braced on four sides by vaults and supported by four columns or piers—giving the appearance of a cross within a square.)

*

Vefa Kilise Mosque

The building now known as the Vefa Kilise Mosque was also expanded in several phases, with the addition of a two-stored annex, a belfry, and a three-domed, porticoed exonarthex with burial vaults beneath its floor.

The Chora Monastery

Of the Palaiologan monuments in Constantinople, the most important to survive is the Chora Monastery, where the additions uniquely represent a single phase of construction.

Restored and lavishly decorated by the statesman and scholar Theodore Metochites c. 1316–21, the twelfth-century naos was enveloped with a two-storied annex to the north, two broad narthexes to the west—the inner topped by two domes, the outer opened by a portico façade, and a domed funeral chapel or parekklesion to the south, with a belfry at the southwest corner.

In all of the Palaiologan complexes, complexity is more important than monumentality in the visual expression, and the new portions may be understood as a response to history, an attempt to establish a symbolic relationship with the past. By 1330, however, the short-lived “Palaiologan Renaissance” had ended in the capital, at least in terms of major church construction.

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki also saw the construction of numerous churches in the Late Byzantine period.

Ambulatory-plan churches

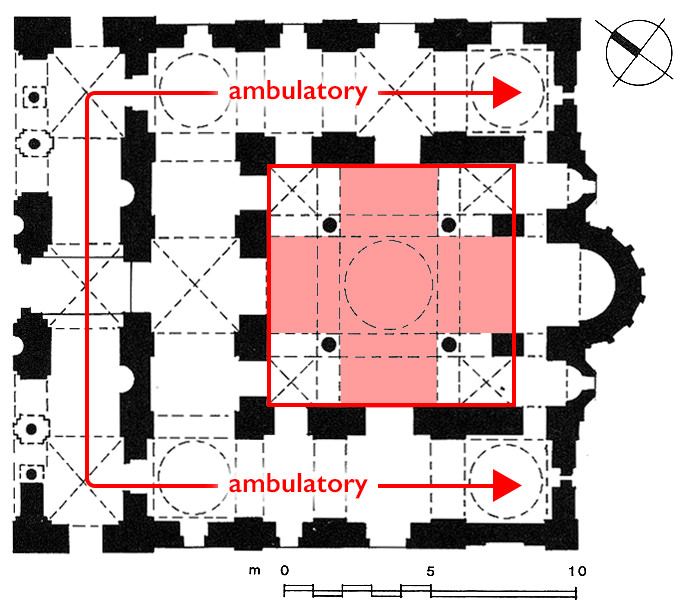

At H. Panteleimon, H. Aikaterini, and H. Apostoloi, all late thirteenth or early fourteenth century in date, an attenuated cross-in-square core was enveloped by a pi-shaped ambulatory. (Something pi-shaped takes the form of the Greek letter Π, pi.)

Topped by multiple domes and opened by porticoes, the auxiliary spaces included subsidiary chapels (see plan below). Although their counterparts in Constantinople clearly served for burials, the functions of the ambulatory in Thessaloniki are less evident. Several simpler, unvaulted churches survive from the same period.

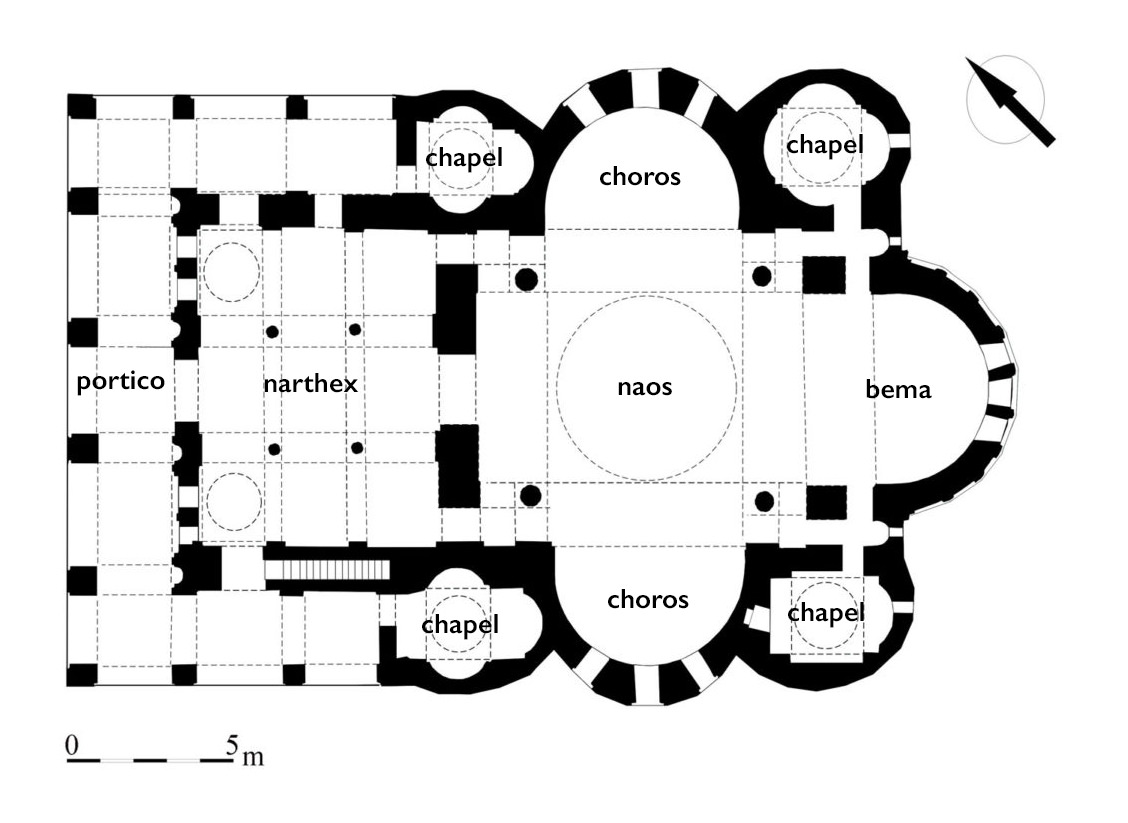

Profitis Elias

The Profitis Elias, built c. 1360 on an Athonite plan (with choroi and subsidiary chapels), demonstrates the enduring vitality of architecture in the city.

Mystras

Mystras (in the Peloponnese in Greece) emerged as a major Byzantine political center with the expulsion of the Latins in the mid-thirteenth century (following their occupation of the region since the time of the Fourth Crusade).

Hodegetria Church at Brontochion Monastery

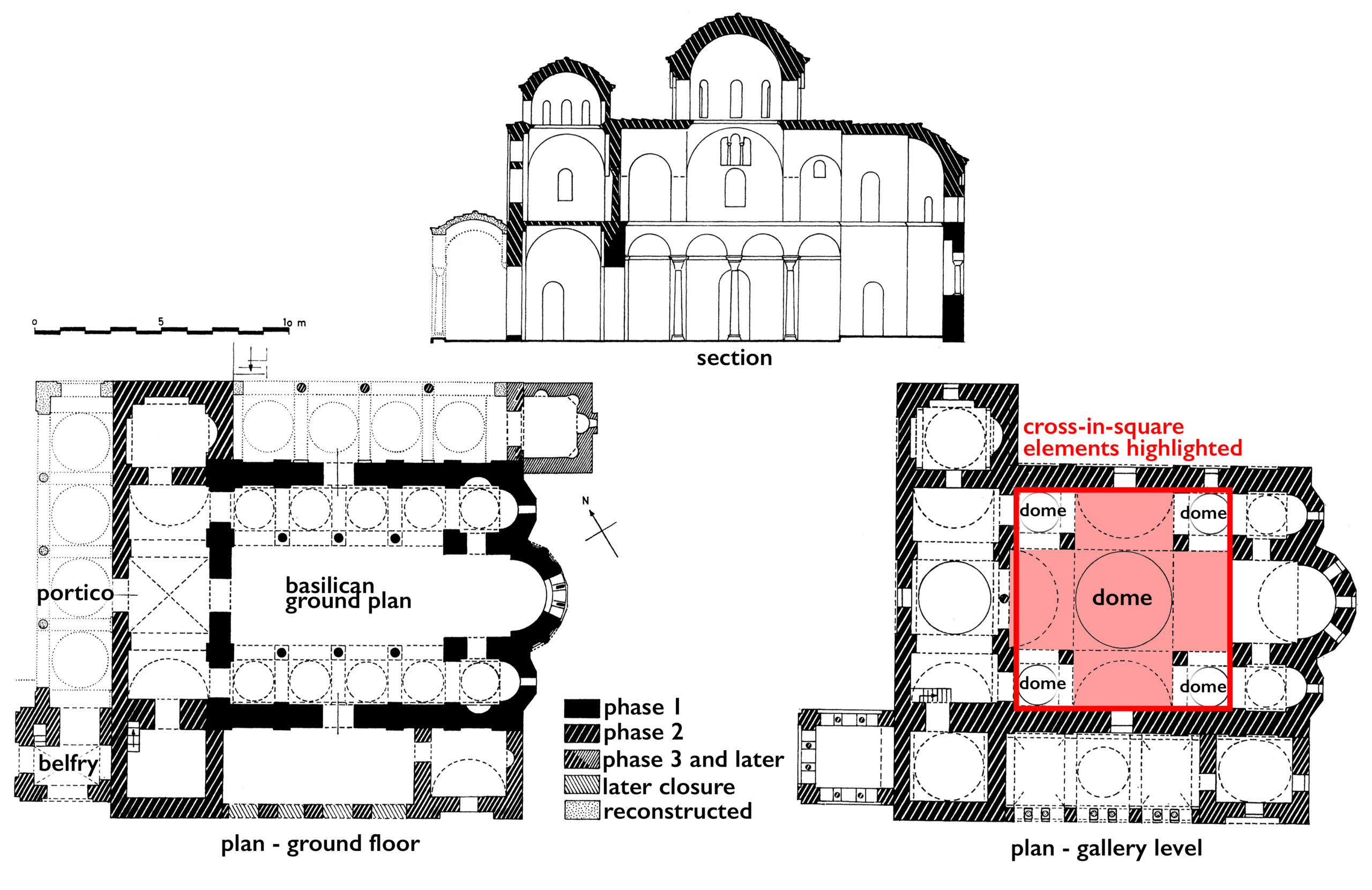

Several churches of the so-called “Mystras type” (named for their location in Mystras, Greece) combine a basilican ground plan with a cross-in-square, five-domed gallery, the whole enveloped by porticoes, a belfry, and additional subsidiary spaces.

The Hodegetria (or Aphentiko) church at the Brontochion monastery, built c. 1310–22, betrays evidence of an ad hoc creation, begun as a simple cross-in-square church.

Pantanassa monastery

The type is repeated as late as 1428 in the church of the Pantanassa monastery.

Churches of the octagon-domed church and cross-in-square types were also constructed in this period. (An octagon-domed church is a centrally planned church with a dome supported above eight points.) Architectural detailing suggests close connections with both Constantinople and Italy.

Bulgaria

Perhaps most significant in this period is the emergence of neighboring powers as creative centers of architecture. Bulgaria remained closest to Byzantium in its architectural developments.

The Pantokrator and Sv. Ivan Aliturgetos at Nesebar

Although more robust in terms of their surface decoration, the late churches of Nesebar, for example, follow the construction techniques and façade ornamentation of Constantinople. The coastal town passed repeatedly between Byzantine and Bulgarian control.

The churches of the Pantokrator and Sv. Ivan Aliturgetos date to the mid-fourteenth century and are most distinctive for their colorful exteriors, combining brick and stone decoration with glazed ceramic disks and rosettes.

*

Serbia

Medieval Serbia experienced some western European influence from the Dalmatian coast in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (as at Sopoćani, c. 1265, illustrated above), but as close ties and political rivalry with Byzantium developed in the fourteenth century, Serbian architecture generally followed Byzantine developments, importing both ideas and masons.

Gračanica Monastery

In many ways, King Milutin’s church at Gračanica, built before 1321, represents the culmination of Late Byzantine architectural design. (Stefan Uroš II Milutin reigned as king of Serbia 1282–1321.) Integrating a highly attenuated cross-in-square naos with a pi-shaped ambulatory, the whole is topped by five domes. With simplified façade arcading and a pyramidal massing of forms, the building exhibits an external clarity that belies its complexity.

*

*

Lesnovo

The reigns of both Milutin and Stefan Dušan witnessed a great deal of construction, often similar to developments in northern Greece. The monastic church at Lesnovo (in modern North Macedonia) built 1341–47, for example, is a grand cross-in-square church with a domed narthex. It would not seem out of place in Late Byzantine Thessalonike in its scale, construction technique, or style.

Ravanica Monastery

Later architecture in Serbia, notably that of the so-called Morava School, is smaller and more decorative, often utilizing the so-called Athonite plan (with choroi and subsidiary chapels), as at Ravanica (1370s), with five domes, or the smaller and simpler Kalenić (after 1407).

Romania

Romania represents a latecomer to the scene. Wallachia (a historical region in south- eastern Romania), liberated from Hungary in 1330, came under the influence of Serbian architecture, while Moldavia (a historical region in north eastern Romania), liberated in 1365, shows a greater originality.

Fifteenth-century churches like that at Voroneţ, built c. 1488, or Suceviţa, built c. 1485, have steeply pitched, heavy overhanging roofs and a diminished dome above a triconch plan, the walls entirely frescoed on the exterior. The origin of this distinctively hybrid architecture is unclear.

Russia

Russia was destabilized in the thirteenth century by the invasion of the Mongols, with the notable exceptions of Novgorod and Pskov, where medieval churches survive from the twelfth century onward.

In Novgorod, churches like the Saviour-on-the-Ilyina-Street (1374), are steep-roofed and roughly built.

As Russia recovered from the Mongol invasions, Muscovy developed its own distinctive architecture, first seen perhaps in the Dormition Cathedral in Zvenigorod (c. 1399).

Moscow emerged as the most important center, and following the fall of Constantinople in 1453, it assumed the role of spiritual leader of the Orthodox world.

In the late fifteenth century, a new architectural impetus arrived from Italy, in the form of imported Italian architects.

The Cathedral of the Dormition in the Kremlin, constructed 1475–79 under the direction of Aristotele Fioravanti, combined details derived from the Cathedral of Vladimir with an Italian Renaissance modular plan, topped by five domes; it became the coronation church.

Cathedrals of the Annunciation and of the Archangel were added to the Kremlin shortly thereafter.

Anatolia

With the defeat at Manzikirt in 1071, much of Anatolia (see map above) passed into the control of the Seljuqs and other Turkic beyliks, but this does not mark the end of Christian architecture in the region.

In the thirteenth century, there is evidence of rock-cut architecture in the Christian communities of Cappadocia (in central Anatolia), as for example at Tatlarin, Gülşehir, and Belisırma.

By the early fourteenth century, the Ottomans emerged as the dominant power in northwest Anatolia, and by the 1320s–30s, the former nomads were actively building, and in a manner technically and stylistically following local, Byzantine practices, although plans and vaulting forms may be more closely aligned with the architecture of the Seljuqs.

The Orhan Mosque in Bursa of the late 1330s corresponds closely to contemporaneous works of Byzantine architecture in its mixed brick and stone wall construction and its decorative details. Many of the same features appear at the church of the Pantobasilissa in nearby Trilye, also from the late 1330s, suggesting that the same workshops were constructing both churches and mosques. At Bursa, the first Ottoman capital (conquered in 1326), two Byzantine churches were appropriated for use as the mausolea of Osman and Orhan.

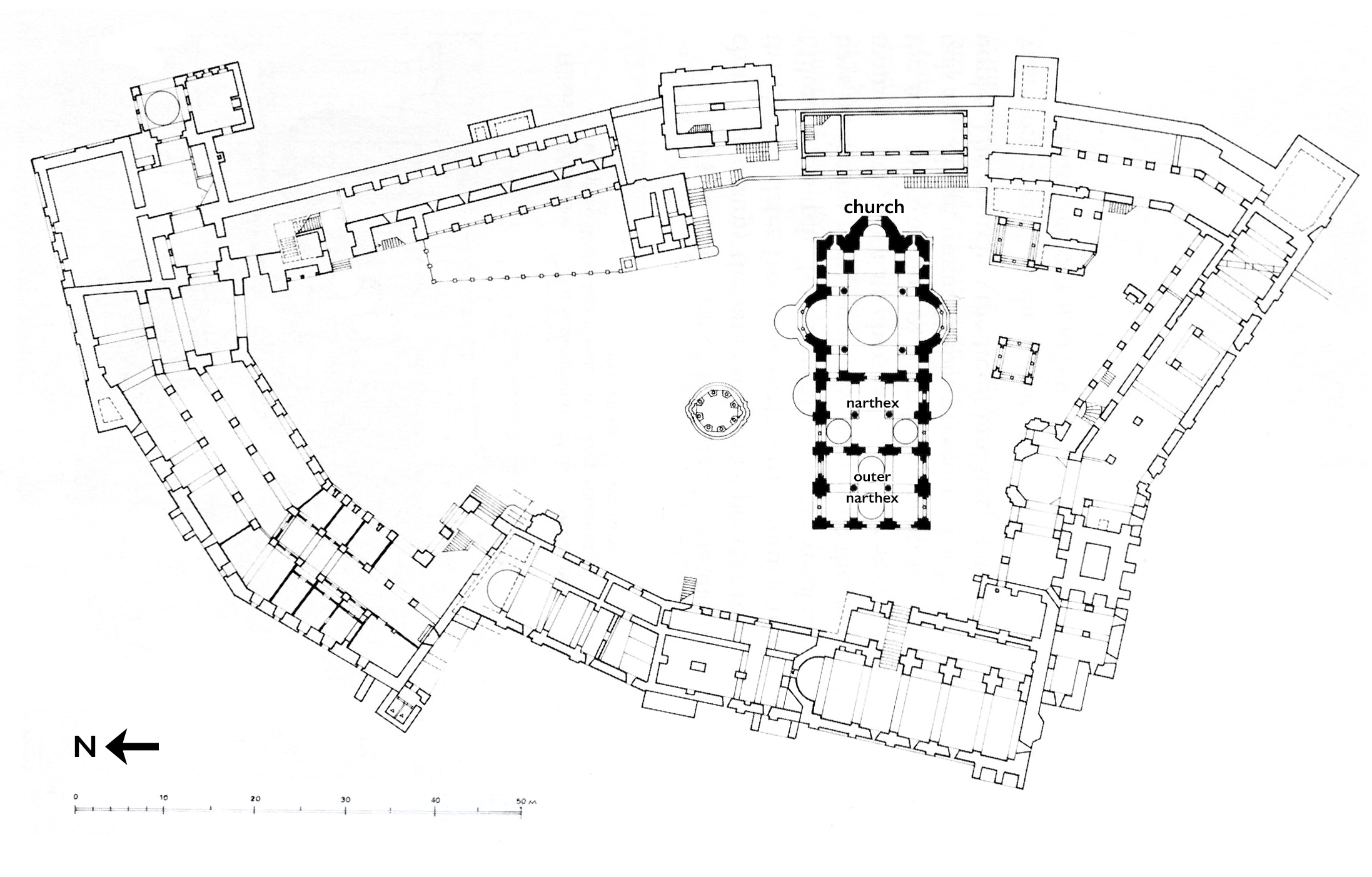

Monasteries

Monasticism follows Middle Byzantine models, as for example at Hilandar on Mount Athos, founded by Milutin c. 1303 (see image above). The freestanding, Athonite-plan katholikon included a large, twin-domed narthex or lite, subsequently expanded with a large, domed outer narthex in the latter part of the century. Both reflect the increased role of the narthex in monastic worship.

Fortified, with the monastic cells lining the wall, the monastery has its refectory set opposite the entrance to the katholikon, with a phiale or holy water font in the courtyard to one side. Similarly planned monasteries appear throughout the Balkans.

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).