41

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

The Fourth Crusade and the Latin Empire

In 1204, the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade (whom the Byzantines referred to as “Latins” or “Franks”) sacked and occupied the Byzantine Capital of Constantinople. In the years that followed, the crusaders established a “Latin Empire” that also included formerly Byzantine regions such as the Pelopponese in southern Greece. In terms of urban developments, the period of Latin control encouraged some construction in the Peloponnese, while having an adverse effect on Constantinople. For all, the physical evidence is limited.

Urban planning in Constantinople

After retaking Constantinople for the Byzantines in 1261, emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos’s refounding of the capital city may have been more symbolic than actual. It included a unique triumphal column positioned before the Church of the Holy Apostles, topped by a statue group of the emperor kneeling before St. Michael. Since Constantine was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles, Michael’s new column may have represented an attempt to present himself as a “new Constantine” or second founder of the city of Constantinople. Unfortunately, the column does not survive and is only known from historical descriptions.

Theodore Metochites, a Byzantine statesman who as a young man had written an encomium lauding the city of Nicaea, strikes a very different tone in the Byzantios, an oration on Constantinople. While recognizing the diminished state of affairs, he attempts to give it a positive spin: Constantinople renews herself, so that ancient ruins are woven into the city’s fabric to assert their ancient nobility. While the intended message is of unchanging greatness, the realities of ruin and desolation are all too apparent.

*

Urban planning in the Peloponnese

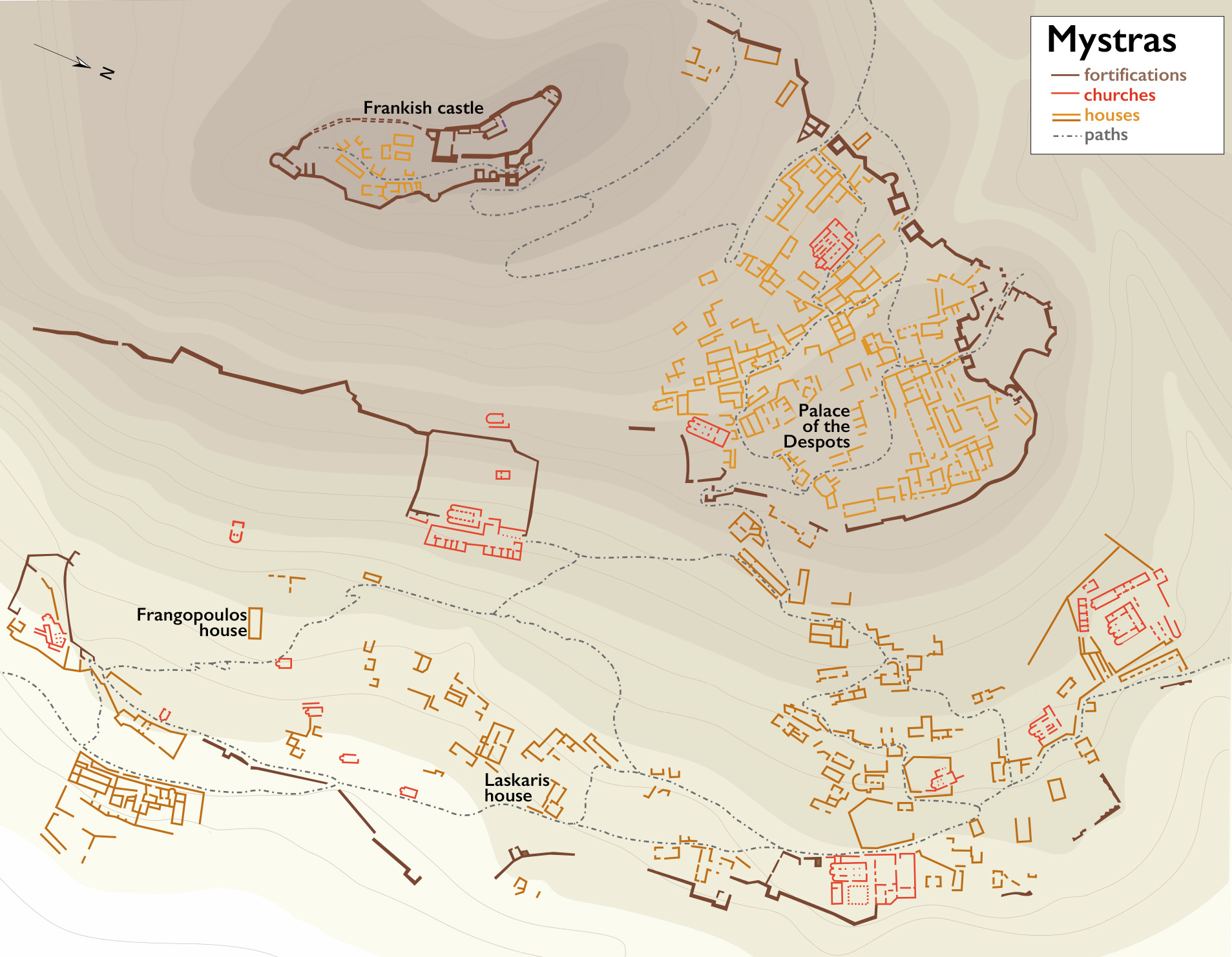

Mystras, a new city of the period, gives a better picture of urban planning. Strategically situated on a hill above the ancient Greek city of Sparta in the Peloponnese (in souther Greece), Mystras developed beneath a Frankish castle—built by Latin occupiers in 1249 following the Fourth Crusade—which the Byzantines captured in 1262. The rugged site with its steep slope offered excellent defenses and did not require a complete ring of walls.

Subdivided internally into an upper and lower city, the streets are often no more than footpaths and too steep for wheeled vehicles; urban planning was at the mercy of the topography. Indeed, many areas within the walls were too steep for construction. Houses often required extensive substructures, and the only sizeable terrace within the city was given over to the Palace of the Despots (more on this below). Markets were probably located outside the walls.

The situation at Late Byzantine Geraki seems to have been similar. Located southeast of Mystras in the Pelopponese, Geraki developed beneath another Frankish hilltop fortress, which was ceded to the Byzantines in 1263.

Domestic architecture

Excavations at Pergamon

The evidence for Late Byzantine domestic architecture is similarly limited. The excavations at Pergamon provide some sense of a neighbor- hood development.

Here the houses consist of several rooms, often with a portico, arranged around a courtyard set off the irregular pattern of alleys and cul-de-sacs. Similar house forms have been noted in other urban situations, with the focus of the house away from the street.

Mystras

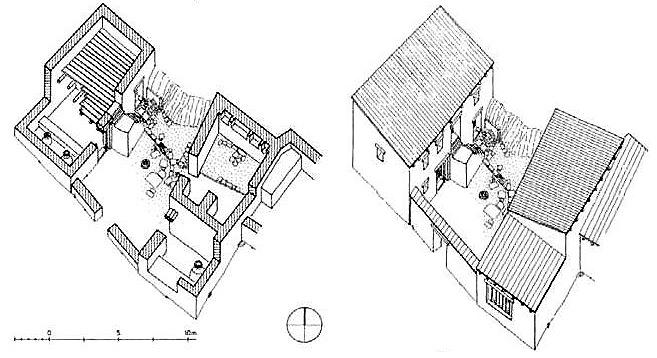

Mystras also provides several good examples, such as the so-called Frangopoulos House and Laskaris House (named for those believed to have inhabited them), both probably from the early fifteenth century. Set into the steep slope, both had vaulted substructures of utilitarian function—cistern, stable, storeroom—to create a level platform for the residence, which consisted of one large room, with a fireplace to the rear and a terrace or balcony facing the view.

Tower of Apollonia

In the countryside, fortified towers often functioned as residences, as at Apollonia (near Amphipolis) and elsewhere in mainland Greece.

Constantinople

In Constantinople, nothing survives of the main imperial residence at the Blachernae Palace, except the so-called Tekfursaray, which may have been a pavilion associated with it. (Blachernae Palace was located in northwestern Constantinople and served as the primary imperial residence in the Late Byzantine period.) Built as a three-storied block set between two lines of the land wall, the lowest level was opened to the courtyard by an arcade (a series of arches carried by columns or piers). The mid level was apparently subdivided into apartments, with the upper level functioning as a large audience hall, with appended balcony and a tiny chapel.

*

*

*

An association with Venetian palaces has been suggested, but the ruined palace at Nymphaeon of c. 1225 provides a useful precedent.At Mystras, the Palace of the Despots grew over the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as several adjoining but independent units. Its last major addition, the Palaiologos wing, follows a three-storied format like that of the Tekfursaray, with an enormous audience hall on the uppermost level, with apartments and storerooms below.

Fortifications

With the increasing insecurity and fragmentation of the empire, defense became a growing concern in the last centuries of the empire.

City walls

Nicaea was provided with a second line of walls in the thirteenth century, and the Laskarids built a series of visually-connected fortresses in an attempt to secure their Aegean territories.

Frankish fortresses in the Peloponnese

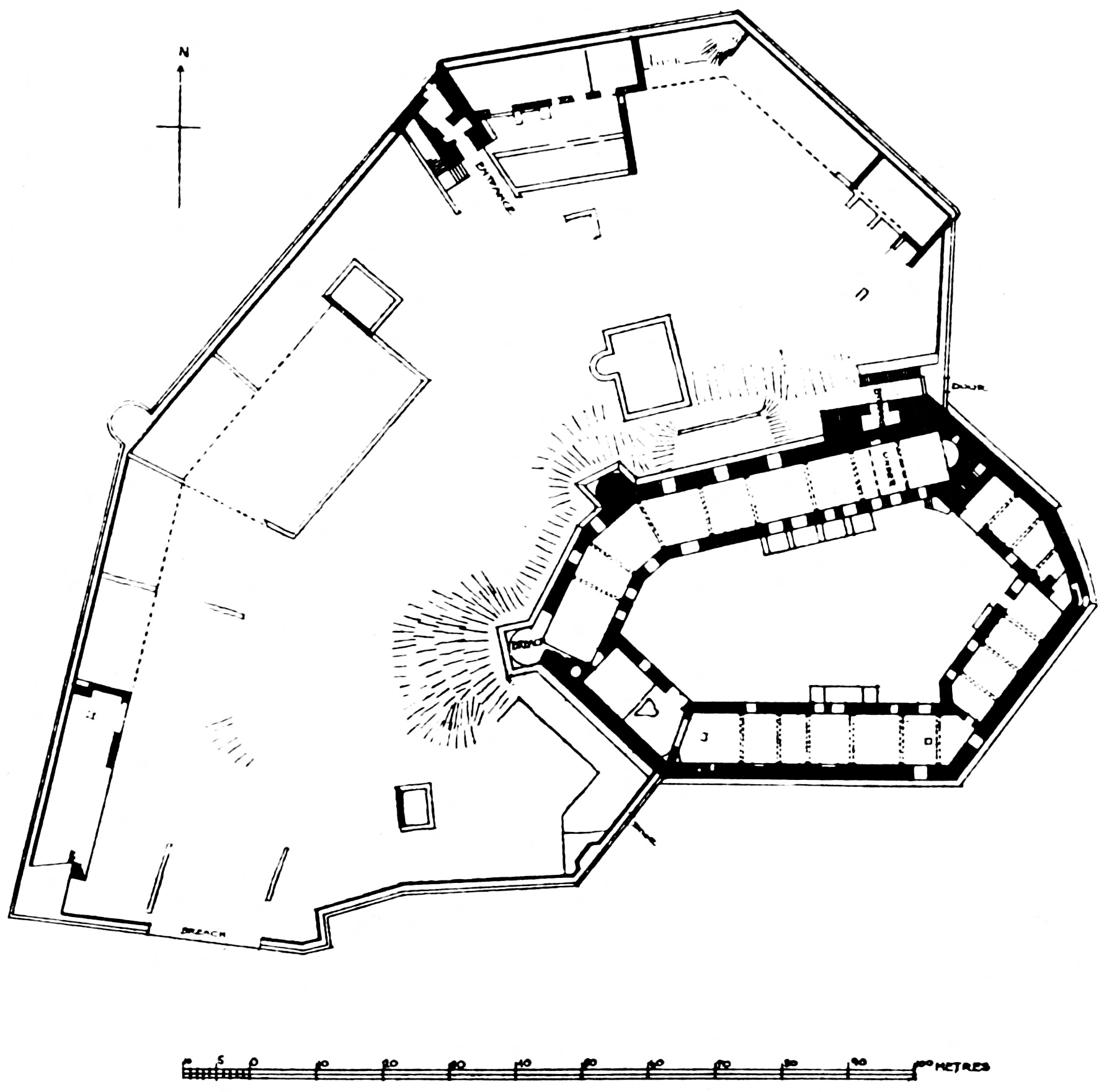

Following the Fourth Crusade, the Franks also constructed fortresses across the Peloponnese in an attempt to secure control of the region, as at Chlemoutsi (see plan below) and Glarentza (now in ruins).

Byzantine fortresses

With the reconquest of Constantinople by the Byzantines, fortresses were either strengthened and expanded (as at Yoros on the Bosphoros) or constructed anew to protect the city against the rising power of the Ottomans to the east.

Among the smaller fortifications of the period, the castle at Pythion in Thrace is noteworthy. Built by John VI Kantakouzenos c. 1331, a large fortified tower quickly expanded with the construction of a second tower and gateway, with inner and outer enceintes. The four-bayed plan of the main tower, with brick vaulting at all levels, and the extensive use of stone machico- lations (floor openings through which stones or other materials could be dropped on attackers) mark Pythion as unique among Byzantine fortifications and at the cutting edge of military technology in the fourteenth century.

*

*

*

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).