24

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

Ruralization

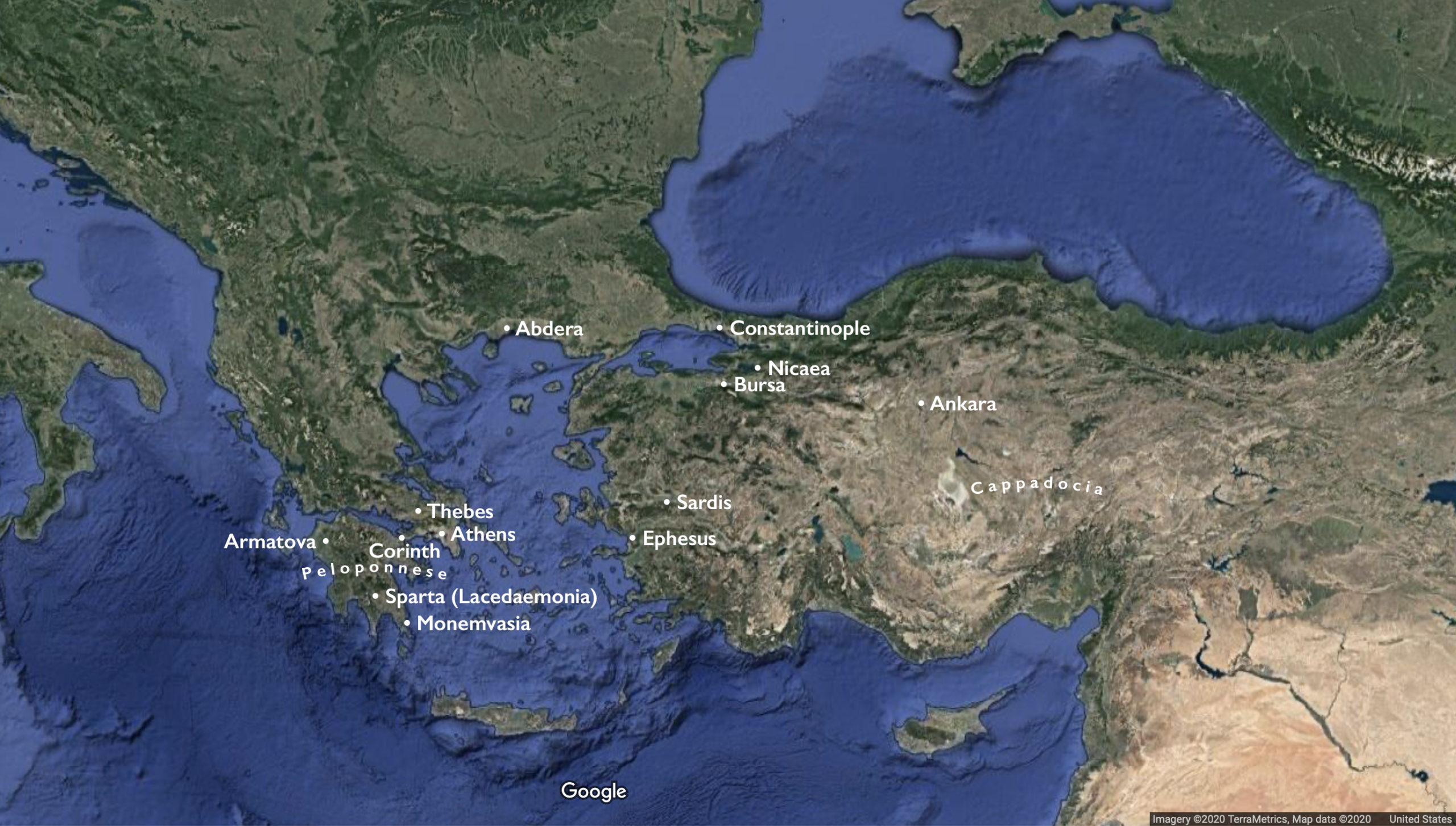

Although churches such as Hagia Sophia are among Byzantium’s best known architecture, the Byzantines also built cities, palaces, houses, and public infrastructure such as aqueducts. Yet secular architecture can often be difficult to assess in the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843–1204). After the sixth century, the Byzantine Empire underwent a process of ruralization, as large centers were depopulated or abandoned, with a demographic shift to the countryside. Often the inhabited area of a city was reduced to its fortified acropolis; at Ankara (an ancient city in Anatolia, which is now the capital of Turkey), Sardis (an ancient city in Anatolia, now located in modern Turkey), and Corinth (an ancient Greek city located in the Peloponnese), for example, the remainder of the ancient city was virtually abandoned. Even Constantinople—the capital of the Byzantine Empire—witnessed a cultural break in this period. Following a plague in 747, Constantine V (reigned 741–75) resettled peasants from Greece and the Aegean Islands (located in the Aegean Sea, off the east coast of mainland Greece) in the capital. Portions of the city fell into ruin, with public services neglected.

*

Urban revivals

A cultural revival began after the middle of the eighth century, but cities never achieved their former prominence. As Byzantine society became more private and inward-turning, the home and family became the dominant social focus, with public architecture limited almost exclusively to defense.

Old cities, new names

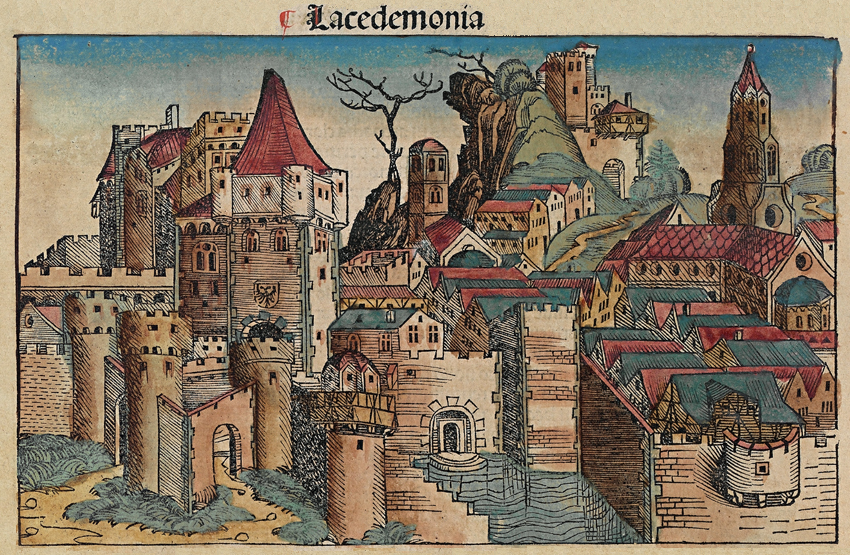

Often cities that had been abandoned were resettled with new names, the older ones forgotten: Abdera (located in northeastern Greece) became Polystylon; Sparta (located in southeastern Peloponnese) became Lacedaemonia. Settlements that were not abandoned shrank, with smaller circuits of fortification; texts refer to these as kastra (“castrum,” plural “castra,” was a Roman term for a fortified military camp) rather than as poleis (“polis,” plural “poleis,” was the Greek word for city).

*

New towns

The few new towns of the period developed because of their strategic or protected locations, as at Monemvasia (a fortified city on a small island off the east coast of the Peloponnese). In Cappadocia (a historical region in Central Anatolia, modern Turkey), numerous new agricultural settlements date from the tenth and eleventh centuries, cut into the soft volcanic rock formations, but these are no more than villages.

*

*

*

*

Reconfiguring ancient cities

At Ephesus—an ancient Greek, and later Roman, city in Anatolia, near the west coast of modern Turkey—the ancient center was gradually aban- doned in favor of the more easily defended hill of Ayasoluk, several kilometers inland, fortified around the church of St. John. At Sparta, the ancient acropolis was reinhabited beginning in the ninth century. In many older sites, the main streets continued to function, but new patterns of growth emerged within the urban rubble.

At Nicaea (modern İznik, located in northwestern Anatolia), both the cardo (the north-south street in an ancient Roman city or military camp) and decumanus (the east-west street in an ancient Roman city or military camp) of the ancient city continued to be used, but this is an almost unique example. New areas of settlement were characterized by growth in an ad hoc manner; streets appeared as the area between private properties, unpaved and unmaintained, as at Corinth and Athens.

Public spaces

Similarly, public spaces were abandoned and their functions replaced by streets of mixed use, with shops, workshops, and residences together. Market fairs and other large gatherings took place outside the walls, as for example the festival of St. John at Ephesus. Conversely, some activities that would have been extramural (“extramural” refers to something taking place outside or beyond the walls) in ancient times moved within the confines of the medieval city; for example, within Constantinople, large areas were devoted to vegetable gardens. More significantly, cemeteries gradually penetrated the city, many associated with religious foundations.

Water supplies

Another element necessary to the city was water. With the declining populations, most aqueducts (an artificial conduit used to supply water to a city from another location) fell into disrepair. The aqueducts supplying Constantinople and Thessaloniki were maintained only with difficulty.

A few new aqueducts were constructed, as at Thebes (an ancient Greek city located in central Greece), and an extensive hydraulic system was developed in some parts of Cappadocia; at Corinth and Bursa (an ancient city in northwestern Anatolia, today one of the largest cities in Turkey), natural springs provided water. In most cases, private systems developed, with wells or cisterns to collect rainwater.

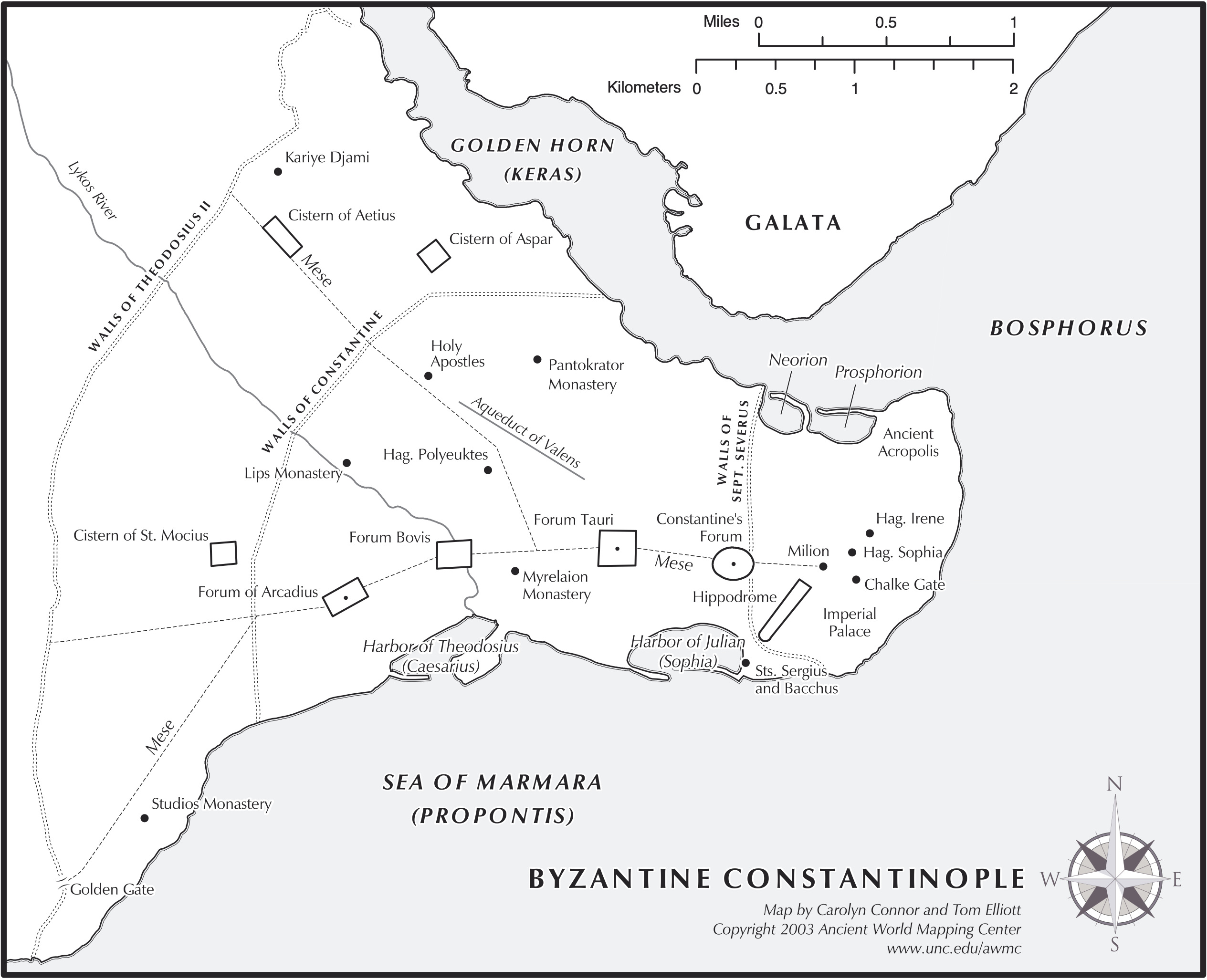

Constantinople

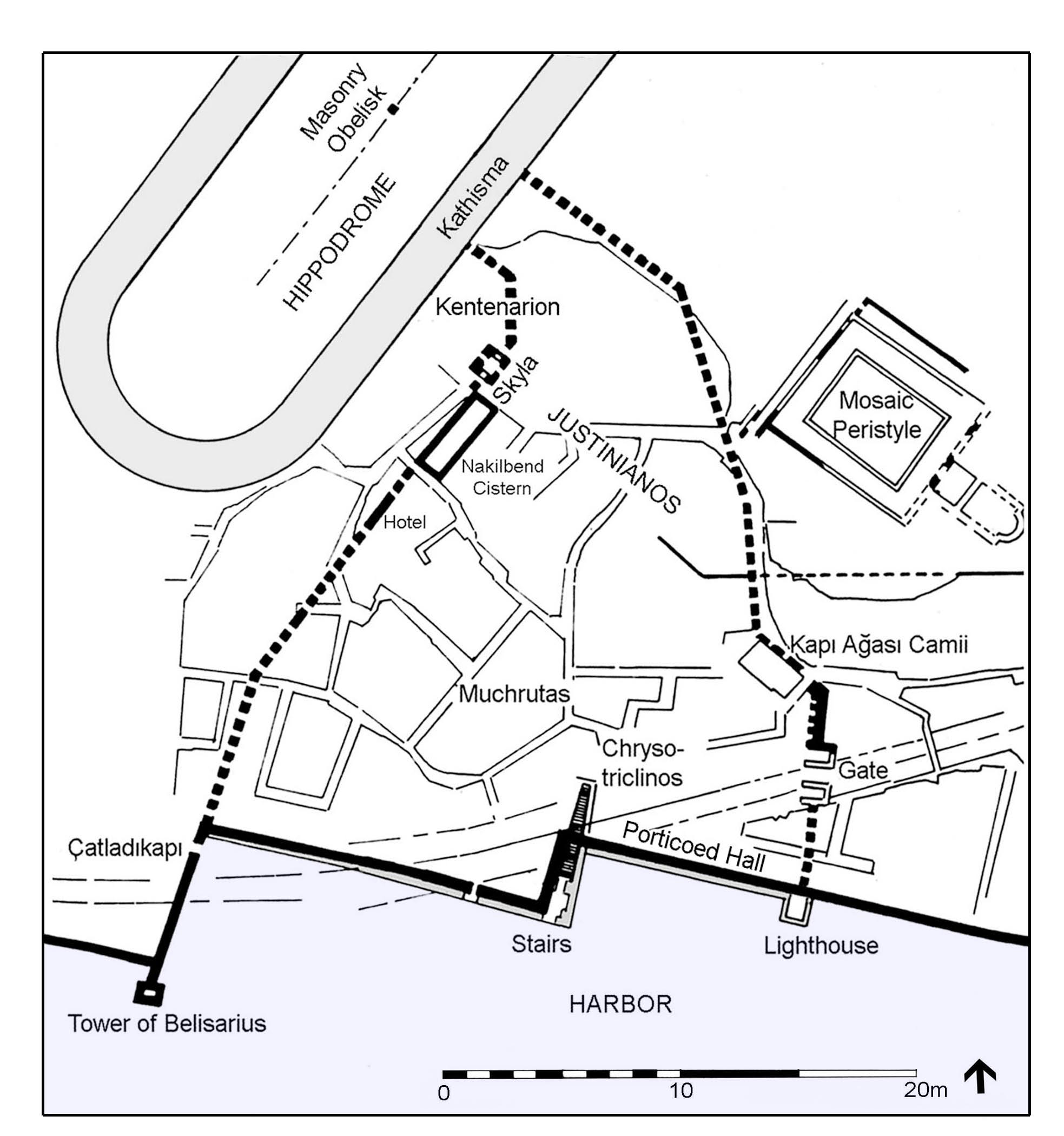

Throughout the period, Constantinople remained unique in its urban character, appreciated by contemporaries for its wealth, its size, its paved streets, and the presence of the imperial court. By the twelfth century, its population may have been as high as 400,000.

The city also retained many of the great monuments of Late Antiquity; its spacious main streets, its forums bedecked with triumphal monuments, its basilicas and public buildings formed the backbone of the medieval city, and they continued to function throughout the Middle Byzantine period—if perhaps in a diminished capacity.

Enough grandeur survived for emperors of the ninth and tenth centuries to stage imperial triumphs (victory celebrations inherited from Rome that featured a triumphal parade into the capital with troops, captives, booty, and the victorious emperor) in the antique manner.

*

*

*

*

Domestic Architecture

Middle Byzantine domestic architecture is poorly preserved. A simple country house was excavated at Armatova in Elis (an ancient district in the Peloponnese in Greece), composed of small rectangular rooms and a porch. At Corinth, excavated medieval houses have courtyards with wells and ovens surrounded by rooms and storerooms. Although offering a small degree of comfort and efficiency, virtually no concern for aesthetics is evident. In Constantinople, multi-storied residences like Roman insulae still existed. In the twelfth century, John Tzetzes describes living in a three-storied tenement, with a priest, his children and pigs above him, and hay stored by a farmer on the ground floor.

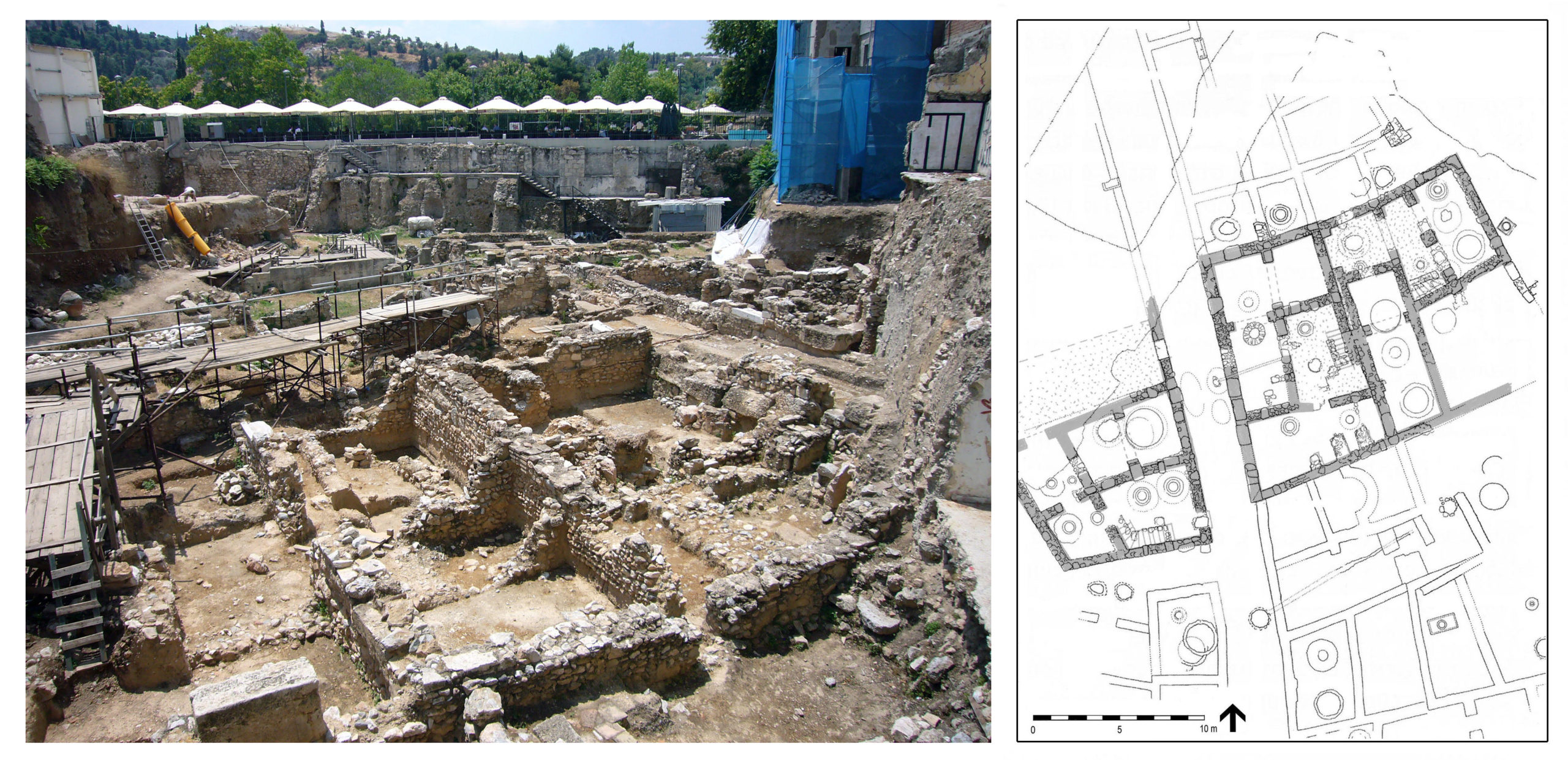

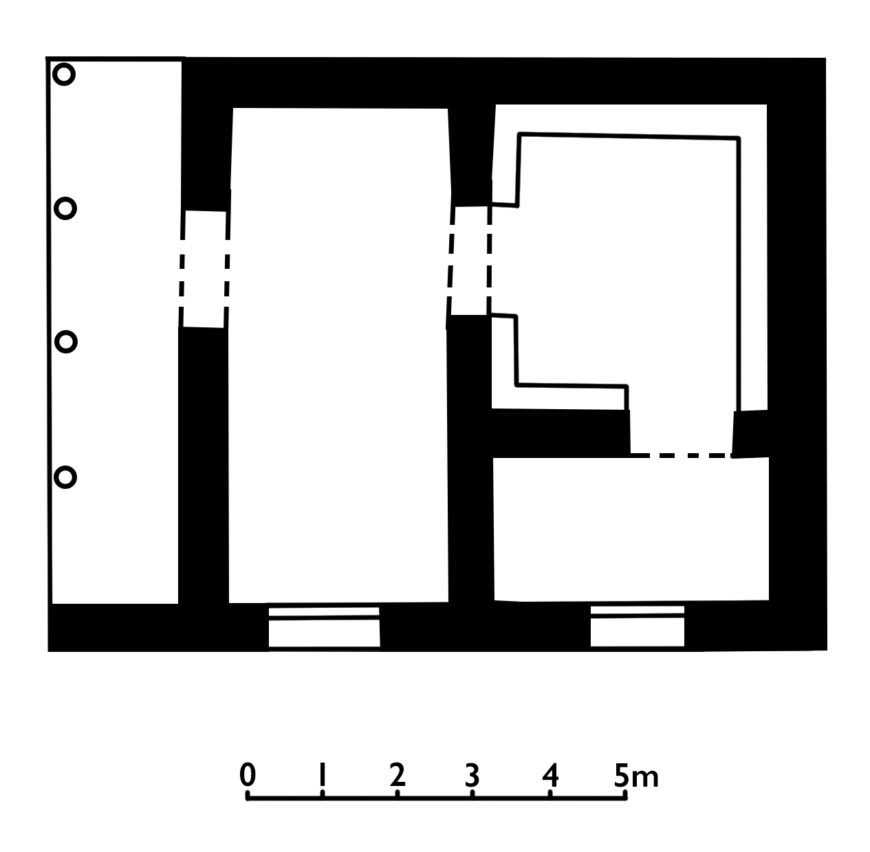

At the Myrelaion in Constantinople, the foundations of a huge rotunda from a Late Antique palace were filled with a colonnaded cistern (for water storage) to form a level platform for the considerably smaller tenth-century Palace of Romanos Lekapenos (reigned 919–44), pi-shaped in plan, with a portico (a structure consisting of a roof supported by columns at regular intervals) along the main facade, and with a chapel off to one side (which survives as the Bodrum Mosque today). Later, the complex was converted into a monastery.

Although known only from excavated remains, such urban forms may be reflected in the rock-cut courtyard dwellings of Cappadocia, such as those found at Çanlı Kilise near Akhisar (see below).

These dwellings similarly have the rooms organized around a courtyard, a porticoed façade, and a chapel. Often the main formal rooms were given special articulation; other rooms may be identified as the kitchen, storerooms, cisterns, dovecotes, and stables.

Private estates grew in size and prominence, and by the twelfth century, the great, privately endowed monasteries and the mansions of the wealthy had become the distinguishing landmarks of the city. By the eleventh century, the monumentality of early forms was commonly replaced by complexity. None of these great oikoi (Greek for house), with their sprawling mansions, courtyards, chapels, and gardens, survives, but their appearance is suggested a document of 1203 describing the Palace of Botaniates, which included gatehouses, two churches, courtyards, reception halls, dining halls, residential units, terraces, pavilions, stables, a granary, vaulted substructures, cisterns, a bath complex, and rental properties. Wealthy estates in the countryside may have been fortified, such as that described in Digenes Akritas, which was surrounded by gardens and defended by walls and towers, and also included a bathhouse and a church.

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).