31

Artwork in focus

Dr. Anne McClanan

The classical past and the medieval Christian present

Why would a Biblical king surround himself with pagans?

The Paris Psalter embodies a complex mixture of the classical pagan past and the medieval Christian present—all brought together to communicate a political message by the Byzantine emperor.

The Byzantine Empire, which ruled areas of the eastern Mediterranean from the fourth through fifteenth centuries, left a dazzling visual legacy that has influenced other medieval Christian and Islamic societies as well as countless artists in our own time.

What is a psalter?

The word “Psalter” in the name of this manuscript is the term we use for books and manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Psalms. Psalters were one of the most commonly copied works in the Middle Ages because of their central role in medieval church ceremony.

The images

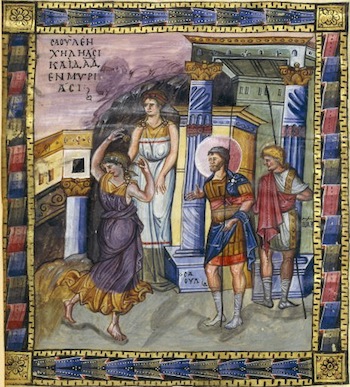

This work was unusually large and lavishly illustrated, with 14 full-page illuminations included in its 449 folios (a folio is a leaf in a book). Eight of these images depict the life of King David, who was often seen as a model of just rule for medieval kings. Because King David was traditionally considered the author of the Psalms, he is shown here in the role of musician and composer, sitting atop a boulder playing his harp in an idyllic pastoral setting. This manuscript so carefully follows models from prior centuries that scholars once thought it was made during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian in the sixth century. Only later did research demonstrate that the Paris Psalter was actually made in the tenth century as an exquisite imitation of Roman work from the third to fifth centuries—in other words, it was part of an intentional revival of the Classical past. Classical style, as a general term, refers to the naturalistic visual representation used during periods when, for example, the Roman emperors Augustus and Hadrian ruled.

Classical revival

The period of classical revival that produced the Paris Psalter is sometimes called the Macedonian Renaissance, because the Macedonian dynasty of emperors ruled the Byzantine Empire at the time. This classical revival followed Byzantine Iconoclasm. The notion that this Byzantine revival of the Roman past was a Renaissance, in the sense of a full-scale revival of classical thinking and art such as in the Italian Renaissance, has been questioned. However, there is no doubt that we see in this, and other contemporary works, a conscious appropriation of elements of the classical artistic vocabulary.

Thus we have the conundrum of the Biblical David encircled by classical personifications (a figure that represents a place or attribute). In this example, the seated woman embodies the attribute of Melody. David’s seated posture with his instrument is likely based on the classical tragic figure Orpheus, usually shown similarly positioned holding his lyre. Likewise the hazy buildings in the background also belong to the Greco-Roman tradition of wall painting. The meaning of the personifications such as the woman, Melody, perched beside David, is intriguing—within the medieval Christian context she presumably has now become a symbol of culture and erudition as opposed to her earlier significance as a minor deity in the pagan classical world.

Notice how the surroundings including plants, animals and landscape differs from the resplendent gold backgrounds used in the imperial mosaics of Justinian and Theodora at Ravenna or the icon we call the Vladimir Virgin. In contrast, David is depicted naturalistically as a youthful shepherd, rather than the grand king he was to become. The classicizing, more realistic style of the figures and the landscape coupled with the overt classical allusions made by the personifications show the pains taken to render a coherent vision uniting subject and style.

Connecting with great emperors of the past?

Other Byzantine art from the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, such as the ivory Veroli Casket, also show a renewed interest in classicism that called upon Late Roman artistic models. The patron of the Paris Psalter perhaps sought to liken himself this way with great emperors of the past by reviving a style that had been out of favor for hundreds of years and perhaps evoked a “golden age.” Choice of artistic style could function as a tool for conveying meaning within the sophisticated Byzantine society at the time.

The Paris Psalter was produced in Constantinople, today known as Istanbul, and takes its name from its modern location, Paris’ Bibliothèque Nationale. The Paris Psalter manuscript, like most western medieval manuscripts, was not made from paper, but from carefully prepared animal skins. Medieval manuscripts were far more rare and precious than mass-produced modern printed books. Large-scale examples, such as this, made for an aristocratic if not imperial patron, show how Biblical art of the highest craftsmanship could serve many purposes for its medieval audience and patrons.