11

Artwork in focus

Dr. Courtney Tomaselli

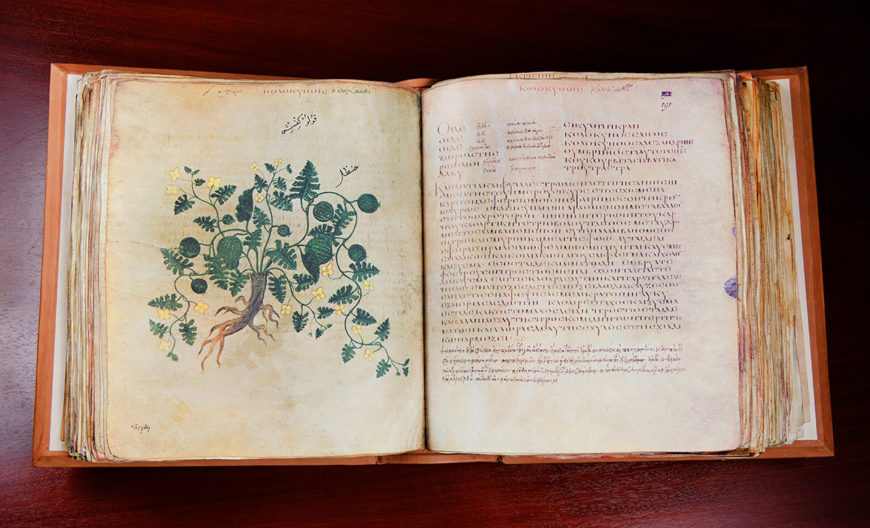

For many, the term “Byzantine art” conjures otherworldly images of holy figures in golden icons and mosaics. But opening the pages of the large, sumptuously illustrated Byzantine manuscript known as the Vienna Dioscurides* you might be surprised to discover a remarkably lifelike illustration of a peacock. Despite its wear, you can still see how the peacock puffs its blue chest and shows off its feathers, practically strutting across the page. The manuscript has 491 folios (leaves of parchment) with more than 400 images of plants and animals. If you keep turning the pages you will notice images of medical experts, therapeutic and poisonous plants and animals, birds, personifications of abstract ideals, and portraits of a princess. This book’s scientific subject matter as well as its lifelike illustrations stand in stark contrast to common clichés about Byzantine art as merely depicting spiritual themes. But who was this book made for, and why?

The manuscript was produced c. 512 C.E. for the imperial princess Anicia Juliana in Constan- tinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire. It is a compilation of several different scientific texts, though they don’t appear in their entirety and have been revised or paraphrased. For the most part, we don’t know where or when most late antique and Byzantine manuscripts were created (or by whom), and the history of their ownership can only rarely be traced (manuscripts are portable objects after all). It is all the more remarkable that we have this information for the Vienna Dioscurides.

The texts of the Vienna Dioscurides

A majority of the the Vienna Dioscurides is devoted to a revised edition of a book written centuries earlier entitled On Medical Matters (De materia medica) by Dioscurides of Anazarbus, a Greek medical practitioner who served as a physician in the Roman army in the first century C.E. His work outlined the therapeutic properties of hundreds of plants and animals. On Medical Matters was popular and influential for 1,500 years until the Renaissance, and enjoyed wide circulation through the nineteenth century. Although several manuscripts of this text survive, the Vienna Dioscurides is the oldest illustrated version. In this manuscript, each entry provides an overview of when and how to harvest a plant as well as instructions for the preparation and use of its various parts.

Also included in the Vienna Dioscurides are:

- an anonymous poem that provides an overview of sixteen healing herbs (Carmen de viribus herbarum)

- prose paraphrases of poems on poisonous animal bites, poisons, and their antidotes (Nicander of Colophon’s Theriaca and Alexipharmaca)

- a poem on fish (Oppian’s Halieutica). Illustrations for this were never begun, and the reserved spaces were left empty (many illustrated manuscripts were left incomplete due to limited time, budget, and/or availability of artists or materials).

- a prose paraphrase of a poem on bird-catching (Dionysius of Philadelphia’s Ornithiaca)

Frontmatter

The Vienna Dioscurides opens with a series of full-page images (unrelated to the text of the De materia medica), beginning with the illustration of a peacock, but this heavily damaged folio is likely out of sequence, and probably originally accompanied the Ornithiaca that comes later in the manuscript (and includes other images of birds).

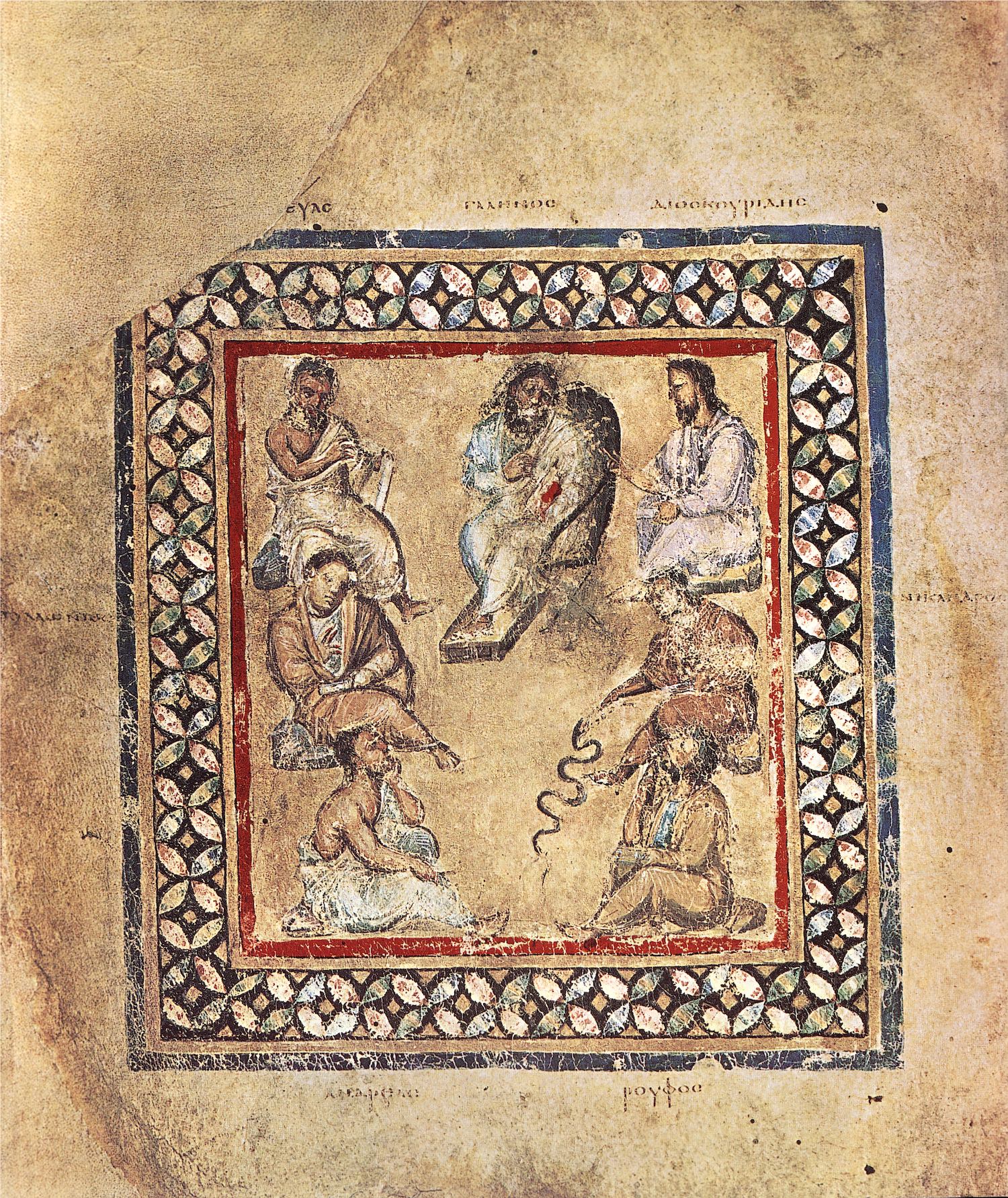

Assuming a misbinding of this first folio, the manuscript was designed to open with two full-page miniatures presenting fourteen famed ancient doctors and authors of medicinal texts who are identified by inscriptions. The centaur Cheiron, who introduced medicine to the world in ancient Greek mythology, sits on his horse legs at the top center of folio 2v. Dioscurides appears in profile on the top right of folio 3v. These doctor images signal the book’s intended medical function and imply a sense of comprehensive knowledge and authority, while also situating Dioscurides as an important figure within the larger medical tradition. They also reflect the book’s status as a luxury manuscript commissioned for an elite patron.

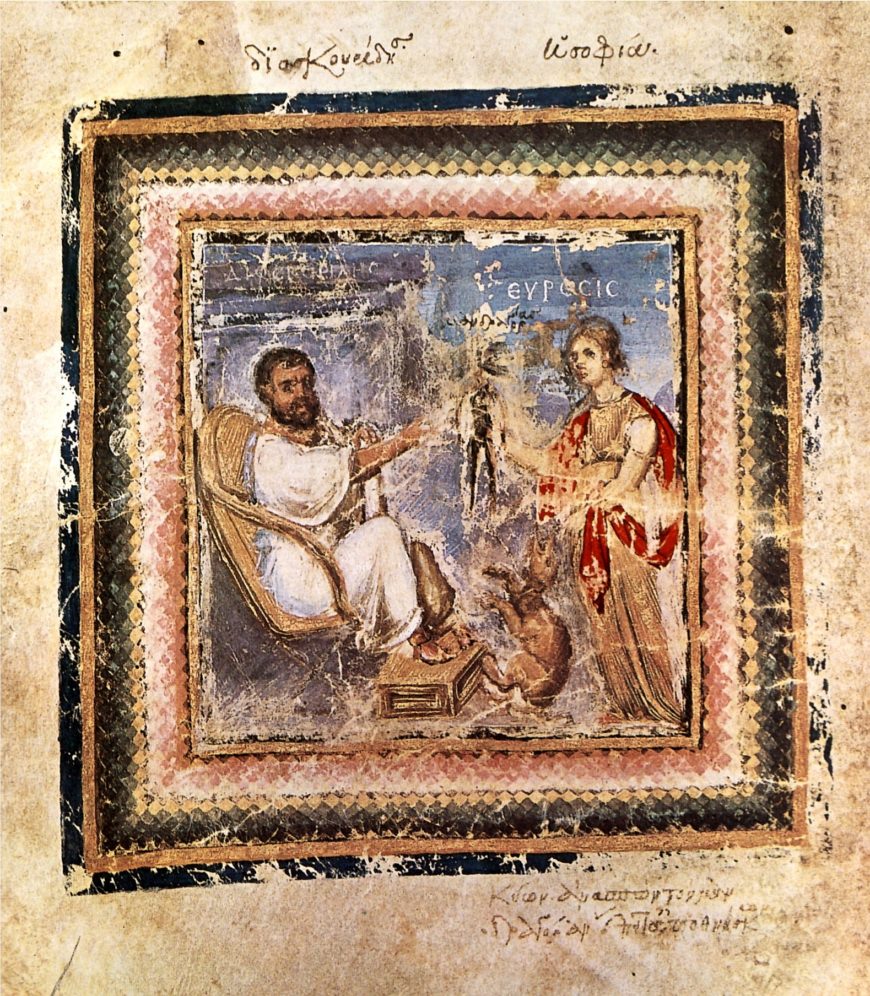

Dioscurides (the first century Greek physician the volume is named for) appears on other pages as well. In one image he takes a recognizable author portrait pose, seated in profile, much as the four evangelists do in Byzantine and western medieval Gospel books. Dioscurides points to a personification of Discovery, who is depicted against an atmospheric blue sky. (Personifications are representations of abstract characteristics in human form. Most are female because they take the gender of the word being represented.) The image suggests the process of gathering fresh specimens outdoors.

Discovery holds the root of a mandrake plant, which was believed could cure headaches, earaches, gout and insanity. Conventional wisdom of the time suggested using starving dogs to harvest the mandrake, which was thought to let out a shriek when pulled from the ground that killed all who heard it.

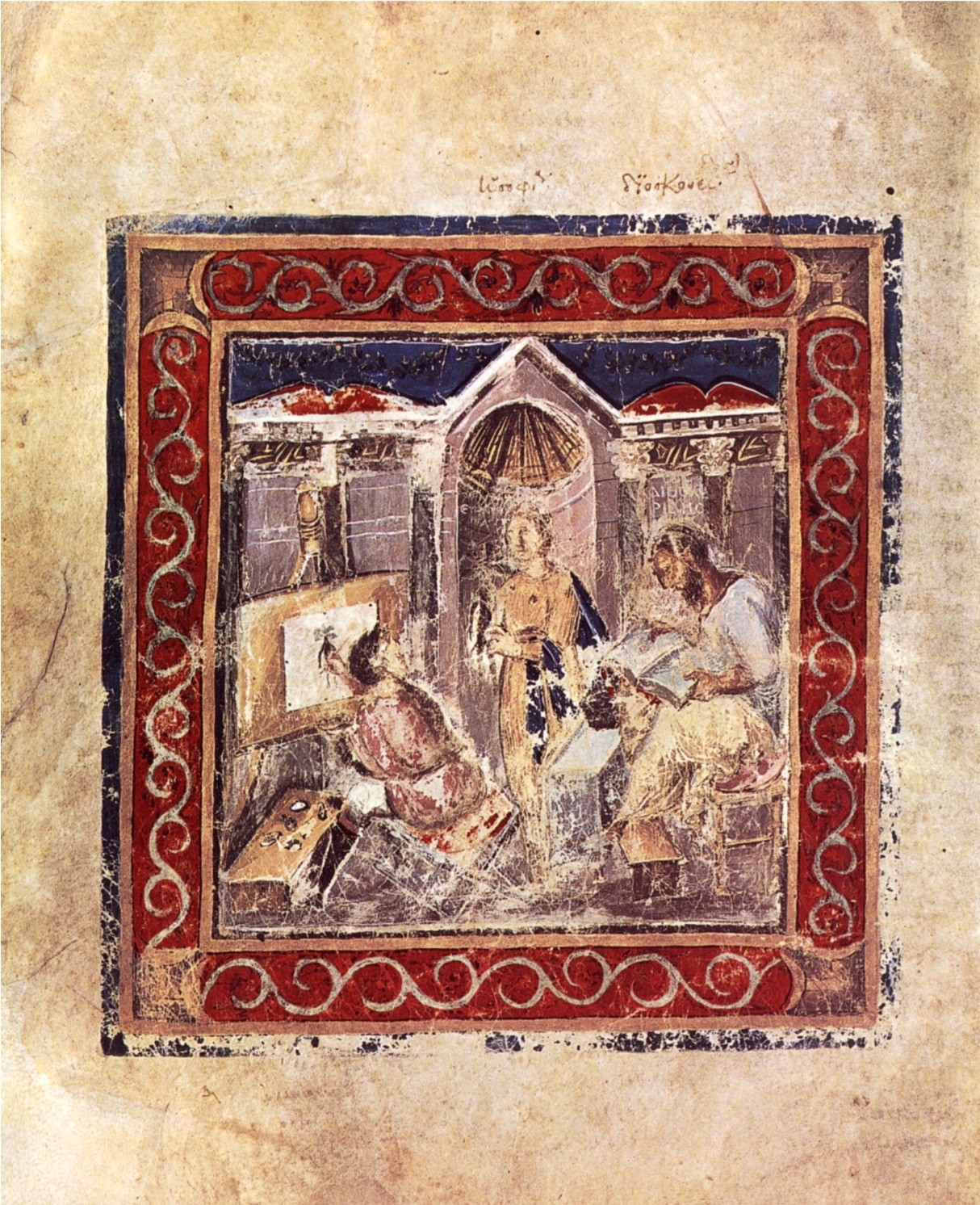

The next image—apparently set in an interior, architectural space—includes a personification of Intelligence who holds out the mandrake for an artist to copy while Dioscurides writes in a codex. Taken together, the images suggest the author’s firsthand observation of the natural world and were likely intended to convey that the information in On Medical Matters (and the Vienna Dioscurides) is accurate and trustworthy.

Dedicatory portrait of Anicia Juliana

While many deluxe Byzantine manuscripts display images of powerful male patrons, such as emperors and high-ranking church officials, the Vienna Dioscurides features an aggrandizing image of Anicia Juliana and illustrates the influential roles that wealthy, aristocratic women could play in the patronage of art and architecture in the Byzantine Empire.

Anicia Juliana was a wealthy aristocrat of imperial descent on both sides of her family and daughter of the short-ruling Western Roman Emperor Olybrius. Both her husband and son held the office of consul. As a wealthy late Roman matron, Juliana would have been responsible for the medical care of her large household, which included both servants and enslaved individuals. For her, the Vienna Dioscurides would have been both a practical and luxurious manuscript.

Juliana sits between personifications of Magnanimity (left) and Prudence (right). Magnanimity holds gold coins while Prudence holds a closed book. The smaller, white-garbed personification of Gratitude of the Arts bows at an angle before Juliana and kisses her red shoe. A putto (child figure, usually with wings) identified as the “Desire of the building-loving woman” holds out an open book onto which Juliana drops gold coins. The frame forms triangles in which may be found the name Juliana (ΙΟΥΛΙΑΝΑ) in large gold letters. Finally, little putti in the spandrels of the frame (the blue triangles) undertake building activities and are difficult to discern due to damage. An interlaced circular composition frames Juliana’s portrait, which is unusual if not unique in manuscript decoration, but appears in late antique floor mosaics, textiles, and jewelry, and is considered apotropaic (something that protects from harm). Surrounding the image of Juliana, it suggests protection for both Juliana and her manuscript.

A black line runs around the inside of the octagon formed by the cabled band that frames Juliana. A damaged dedicatory acrostic—a poem using letters in each line, usually the first letter, to spell out a word or a phrase—is printed on this line. The poem spells out Juliana (ΙΟΥΛΙΑΝΑ) and is as follows:

Hail, oh princess, Honoratae extols and glorifies you with all fine praises; for Magnanimity allows you to be mentioned over the entire world. You belong to the family of the Anicii, and you have built a temple of the Lord, raised high and beautiful.1

In this poem, the people of the Honoratae district of Constantinople seem to be thanking Juliana for her patronage of a “temple,” that is a church, in their neighborhood. The historian Theophanes mentions that Juliana paid for the construction of a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary in the Honoratae district of Constantinople in 512 C.E., providing an approximate date for the creation of the manuscript, assuming the book was commissioned to thank Juliana around the same time she built the church in Honoratae.

Juliana, described as a builder and patron in the Vienna Dioscurides, commissioned or renovated multiple churches in Constantinople. Her crowning achievement, the church of St. Polyeuctus (now in ruins), displayed a dedicatory inscription spanning the walls of its nave comparing her to emperors Constantine, Theodosius, and the biblical King Solomon — all famous royal founders and builders.

Juliana appears enthroned on a gryphon-headed backless seat wearing purple and gold clothing, red shoes, and a diadem-like headdress. Her garments are reminiscent of the imperial depictions of Justinian and Theodora in the sixth-century mosaics in San Vitale in Ravenna. Juliana sprinkles gold coins, which was an act often performed by a new consul taking office. This elevated depiction clearly reflects her aristocratic status, but also seems to suggest imperial authority, raising questions about why Juliana was depicted in this way and if she aspired to rule.

The De Materia Medica

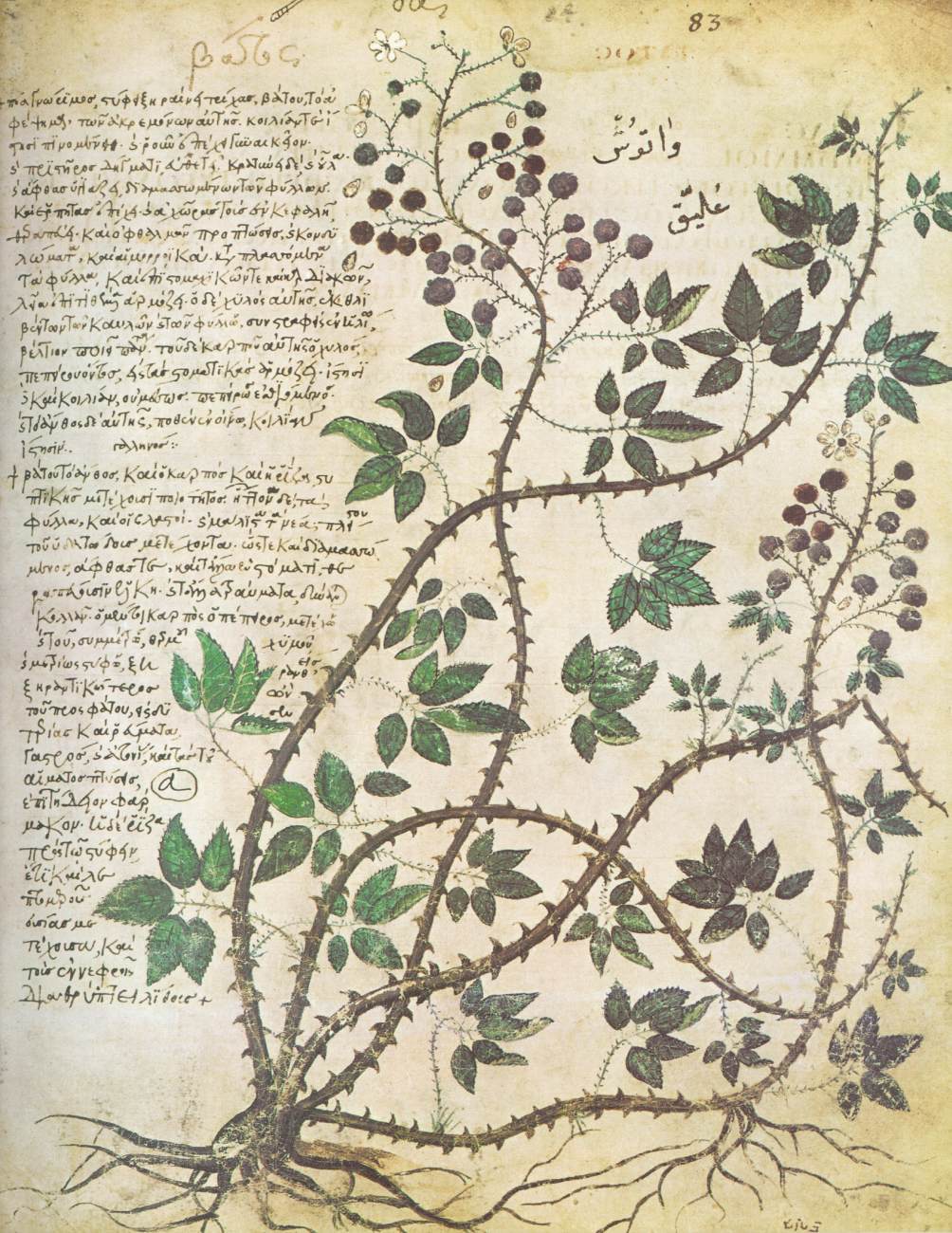

On Medical Matters (De materia medica) comprises approximately three-quarters of the manuscript and most of its original illustrations have been preserved. Generally, these are full-page illustrations of plants or animals paired with corresponding text in Greek uncial (upper case script) across an opening or on the other side of its folio. Most illustrations, such as that of the blackberry bramble, show multiple points in plants’ life cycles for aid in use and harvest. In this graceful illustration, the thorny plant seems to grow before our eyes as it twists and winds diagonally upward across the page, sprouting leaves, blossoms, and berries of various sizes.

But while these illustrations seem highly naturalistic, they do not entirely correspond with nature. Pliny the Elder, a first century C.E. author and naturalist, warned against illustrating herbal texts due to the potential for inaccuracies in the drawings. Artists of the Vienna Disocurides did not work from life but probably copied images from large painted wooden panels, although they might have copied from other illustrated manuscripts.

Illustrations to the remaining texts

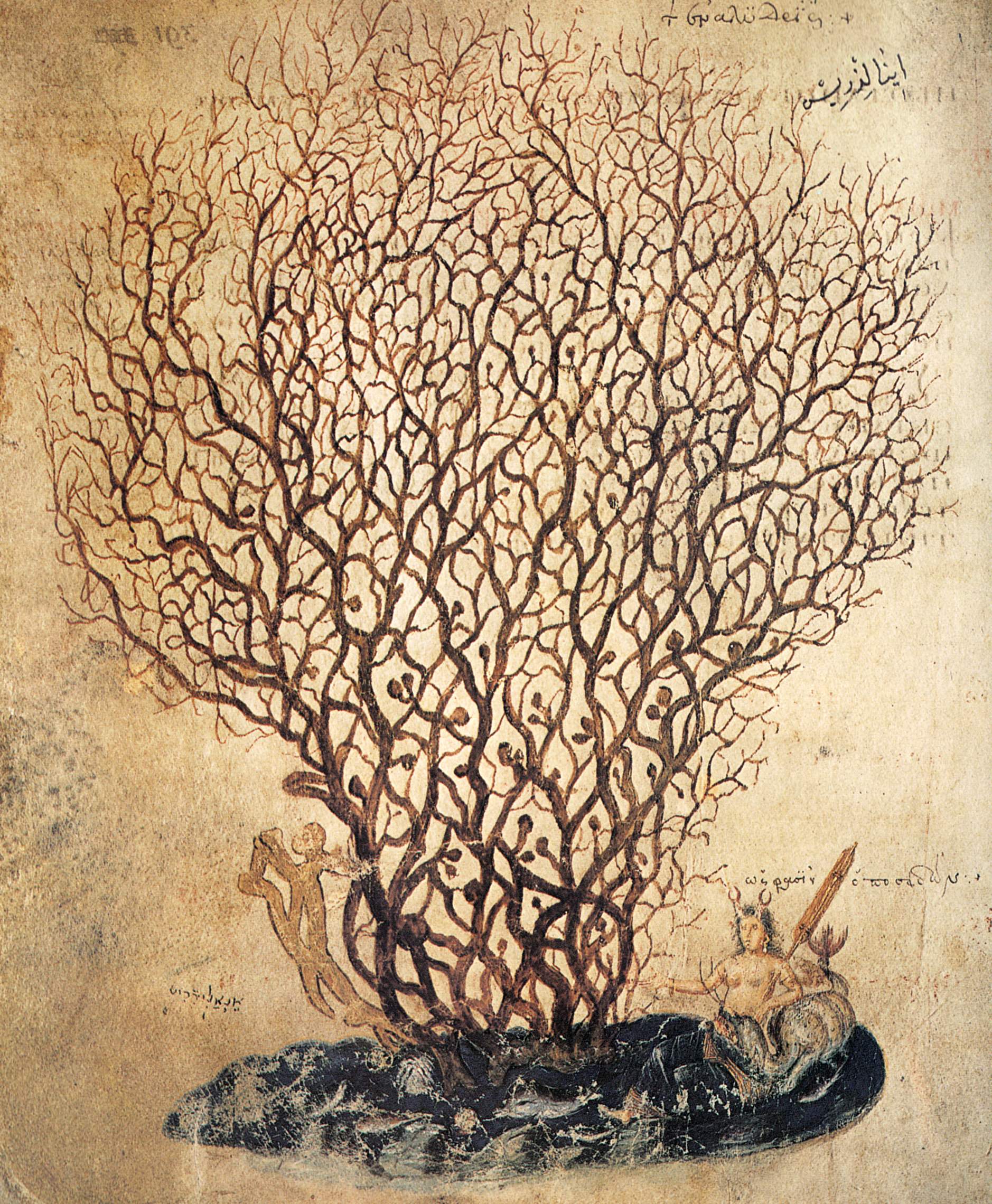

The Carmen de viribus herbarum is punctuated by one full-page painting of coral, thought to be a plant in antiquity. The dense, maze-like coral rises from a body of water, which is occupied by a fantastical personification—likely of the sea—with lobster claws in her hair, as well as a sea monster and additional sea creatures. The rest of Carmen de viribus herbarum features smaller illustrations interspersed within the text.

In the next text, the Ornithiaca, a poem about bird-catching, there is a full-page illustration of twenty-four birds within a gridded frame. The lifelike birds in the full-page illustration seem poised to escape their cage: several step over the frame or extend heads, beaks, or tail feathers outside of their allotted squares.

The Afterlife of the Manuscript

The Vienna Dioscurides remained in Constantinople (today Istanbul) until the late 1560s. Plant names written in Greek minuscule, Latin, Old French, Hebrew, and Arabic reveal its continued use as it it passed through the hands of those controlling Constantinople over the 1000+ years following its creation. It was copied many times and restored in 1406 when it resided in the Monastery of St. John Prodromos.

The Vienna Dioscurides was eventually acquired by Moses Hamon, a Jewish physician close to the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The Holy Roman Empire’s ambassador to the Ottoman court in the 1550s saw the manuscript while in Constantinople and encouraged its eventual purchase by Emperor Maximilian II, noting the contents, illustrations, and old age of the manuscript. In 1592 it was deposited in the Imperial Library in Vienna, which later became the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library), where the Vienna Dioscurides currently resides.

Notes:

* The colloquial name, “Vienna Dioscurides,” refers to the manuscript’s modern location in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, and the author of its primary text, Pedanius Dioscurides of Anazarbus.

[1] Bente Kiilerich, “The Image of Anicia Juliana in the Vienna Dioscurides: Flattery or Appropriation of Imperial Imagery?,” Symbolae Osloenses 76, no. 1 (2001): p. 171.

Additional resources

Facsimile included in Dioscorides Pedanius, Der Wiener Dioskurides: Codex Medicus Graecus 1 Der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, ed. Otto Mazal, 2 vols. (Graz: Akademische Druck u. Verlagsanstalt, 1998).

M. Aceto et al., “First Analytical Evidences of Precious Colourants on Mediterranean Illuminated Manuscripts,” Spectrochimica Acta. Part A, Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy vol. 95 (2012), pp. 235–45.

Leslie Brubaker, “The Vienna Dioskorides and Anicia Juliana,” in Byzantine Garden Culture, ed. Antony Robert Littlewood, Henry Maguire, and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2002), pp. 189–214.

Walter Emil Kaegi, Anicia Juliana (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Bente Kiilerich, “The Image of Anicia Juliana in the Vienna Dioscurides: Flattery or Appropriation of Imperial Imagery?,” Symbolae Osloenses, vol. 76, no. 1 (2001): 169–90.

Stavros Lazaris, “Scientific, Medical and Technical Manuscripts,” in A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts, ed. Vasiliki Tsamakda, Brill’s Companions to the Byzantine World 2 (Boston: Brill, 2017), pp. 55–113.

Geoffrey S. Nathan, “The Vienna Dioscorides’ Dedication to Anicia Juliana: A Userpation of Imperial Patronage?,” in Basileia: Essays on Imperium and Culture in Honour of E. M. and M. J. Jeffreys, ed. Geoffrey S. Nathan and Lynda Garland, Byzantine Australiensia 17 (Virginia, Queensland, Australia: Centre for Early Christian Studies, Australian Catholic University, 2011).

Dioscorides Pedanius, De Materia Medica: Being an Herbal with Many Other Medicinal Materials: Written in Greek in the First Century of the Common Era: A New Indexed Version in Modern English, ed. Tess Anne Osbaldeston and Robert P. Wood (Johannesburg: IBIDIS, 2000).

Joshua J. Thomas, “The Illustrated Dioskourides Codices and the Transmission of Images during Antiquity,”The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 109 (2019), pp. 241–73.