Are we there yet? The Utilization of UDL Principles to Optimize Learning for Linguistically Diverse Learners in Higher Education

Katheryne Stewart

Abstract

The concept of accessibility in education is an exceptionally broad topic and one for which it can be challenging to articulate a focus for discussion. It could be argued that accessibility, in its most intuitive form, involves providing equity of access to those who have been formally diagnosed with identified intellectual, developmental, physical or mental barriers. It is, of course, vital for accommodations to be afforded for such conditions through adequate distribution of funding resources to ensure an equitable learning platform for these students. However, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (n.d.) requires that truly accessible education include, not only physical accessibility, and the provision of necessary supports/accommodations to ensure students with disabilities have equal opportunity in their education but also to provide accessible curricula, delivery, and evaluation methodology, as well. This suggests that institutions of higher education must go well beyond the traditional accommodation office to offer support to students and in doing so, through best practices in curriculum design, teaching and learning, will then include students who may be marginalized from these formal diagnoses, such as those students with cultural and linguistic diversity (CLD). The diversity of learners is ever-growing in Canada within higher education, and thus, to assure an accessible pedagogical experience for all, institutions should broaden their definitions of accessibility to include students who are on a spectrum of ability, and ultimately, include those who have not customarily been defined as the benefactors of accessibility policies. This chapter will provide an exploration of the challenges and barriers faced by culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students in higher education who may be omitted from traditional definitions of appropriateness for access to accommodation measures offered by Canadian institutions. To effectively implement accessible curricula, delivery, and evaluation methodology for all students, the relevance and potential impact of the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework will be discussed from the perspective of CLD learners.

Introduction

There is a legal obligation for all publicly funded colleges and universities in Canada to operate an Accessibility Services (AS) office to coordinate and provide accommodations and services to students with disabilities (Transition Resource Guide, n.d.). The nomenclature for such offices often includes either the word ‘disability’ or ‘accessibility’ in their names, but the word ‘accessibility’ is becoming more commonly used, emphasizing that the environment should be adapted rather than the individual.

Common accessibility requests include those students with learning disabilities, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), mental health disorders, deaf or hard-of-hearing, and blind or low vision (Transition Resource Guide, n.d.). These are, of course, vital conditions to be addressed through the adequate distribution of funding resources to provide an equitable learning platform for all students engaged in higher education. In contrast, accessibility and inclusive education in general can be challenging to define, depending on whether institutions adopt a narrow or more broad view of what students should be the target of these initiatives (Haug, 2017; Kumar & Wideman, 2014). However, in higher education, where the diversity of learners is ever-growing in Canada, the most utilized definitions of accessibility and accommodation tend to exclude students who are on a spectrum of ability, including those who have undiagnosed issues, or do not seek assistance, as well as those with cultural and linguistic diversity (Mohler & Godin-Jacques, 2023; Ward, 2012).

Rising Diversity in Higher Education

There is a growing trend of increased enrolment of students with disabilities in Canadian universities; 24% of first-year university students in Canada self-declare having a disability, however, only 6 to 9% of those students seek accommodation (Campbell, 2022). There has also been a significant increase in the enrolment of international students in tertiary education across the country (Statistics Canada, 2023, 2024). Canada is cited as the leader in the internationalization of higher education, with international students comprising 29% of the total of those enrolled in all forms of tertiary education in the country (Statista, 2022). The number of international students enrolled in Canadian public postsecondary educational institutions more than doubled in a decade, while their share of total postsecondary student enrolments worldwide, increased from 7% to 18% in that same period (Statistics Canada, 2024).

There is a growing trend of increased enrolment of students with disabilities in Canadian universities; 24% of first-year university students in Canada self-declare having a disability, however, only 6 to 9% of those students seek accommodation (Campbell, 2022). There has also been a significant increase in the enrolment of international students in tertiary education across the country (Statistics Canada, 2023, 2024). Canada is cited as the leader in the internationalization of higher education, with international students comprising 29% of the total of those enrolled in all forms of tertiary education in the country (Statista, 2022). The number of international students enrolled in Canadian public postsecondary educational institutions more than doubled in a decade, while their share of total postsecondary student enrolments worldwide, increased from 7% to 18% in that same period (Statistics Canada, 2024).

As institutes of higher education endeavor to implicitly address diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging in standard campus practices, internationalization of the student population has become an important methodology to enhance international collaboration, as well as global access to knowledge and diversity (Evmenova et al, 2024; Fovet, 2019); however, more pragmatically, the significant economic competition among institutions has necessitated that colleges and universities proactively pursue increased international student enrollment (Altbach & Knight, 2007; Fovet, 2019). With scarce resources and a simultaneous increase in expectations to effectively meet the needs of all learners, this rapid internationalization has led to the development of pedagogical tension and challenges for institutions (Robertson, 2010).

Striving to Meet the Accessibility Needs of All Students

The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC, n.d.) defines an accessible educational system as one in which persons with disabilities can “access their environment and face the same duties and responsibilities as everyone else, with dignity and without impediment.” This is expanded further and requires the provision of physical accessibility, necessary supports/accommodations to ensure all students have equitable access and opportunity in their education, as well as accessible curricula, and accessible delivery and evaluation methodology.

Offices to assess and implement accommodations for learner diversity are found on campuses across Canada, and demand for such services has increased. The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario found registrations for such services within Ontario colleges and universities increased by nearly 80% between 2013-14 and 2020-21. The growth in demand for accessibility accommodations has been accompanied by increased complexity of the supports required, as well as an increasing number of students presenting with multiple disabilities (Lanthier et al, 2023). Institutions also provide specific support options for CLD students, but these are generally focused on housing or accommodation, legal and financial aid, opportunities for networking, mentorship, and meeting other students (EduCanada, n.d.).

The OHRC requires institutions to ensure accessible curricula, and accessible delivery and evaluation methodology for all forms of diverse learners, and yet, the evidence around the success of these initiatives for CLD learners is mixed at best. Many of these CLD students face major barriers to success due to challenges with oral and written expression within an academic context. Additional factors that can dramatically alter learning for CLD students are a cultural gap around understanding the purpose and mechanisms of group work, the implicit expectations relating to assignments, the reliability of sources and ways to access them, as well as the etiquette around communication with instructors (Fovet, 2019).

As the instructor of a Career Success class at a major Ontario College, the learning experience in Canada for CDL learners is a topic of personal curiosity and some frustration. The class this semester is 100% comprised of students for whom English is not a first language and includes students from predominantly South Asian countries, including India, Nepal, and the Philippines. In the previous semester, the percentage of CDL learners was 95%. From a first-hand perspective, the struggles to access and navigate written and verbal curricula in an academic environment for these students is evident. From reluctance to actively participate in learning, and a tendency to not seek clarification, to misinterpreting written text and rubrics for assignments, I witness weekly that we are not serving these students well. On reflection of one’s own skills and abilities as an instructor, there is certainly much to learn, but also, there may be significant opportunities within the curriculum itself which, with altered design measures, could improve student engagement and outcome success for CDL students. Framing the issues of linguistically diverse learners in higher education within the context of accessibility and course design emphasizes the importance of creating inclusive environments and educational practices that cater to diverse linguistic backgrounds.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) as an Instrument to Address All Diversity

The design of programming and curricula in education involves a comprehensive understanding of the learners’ characteristics, the instructional environment, and any additional factors that could influence the learning outcomes for these students. While there are many commonalities among learners within higher education, individual student preferences, abilities, and experiences, introduce enormous variability among these populations (Gronseth et al, 2021).

The design of programming and curricula in education involves a comprehensive understanding of the learners’ characteristics, the instructional environment, and any additional factors that could influence the learning outcomes for these students. While there are many commonalities among learners within higher education, individual student preferences, abilities, and experiences, introduce enormous variability among these populations (Gronseth et al, 2021).

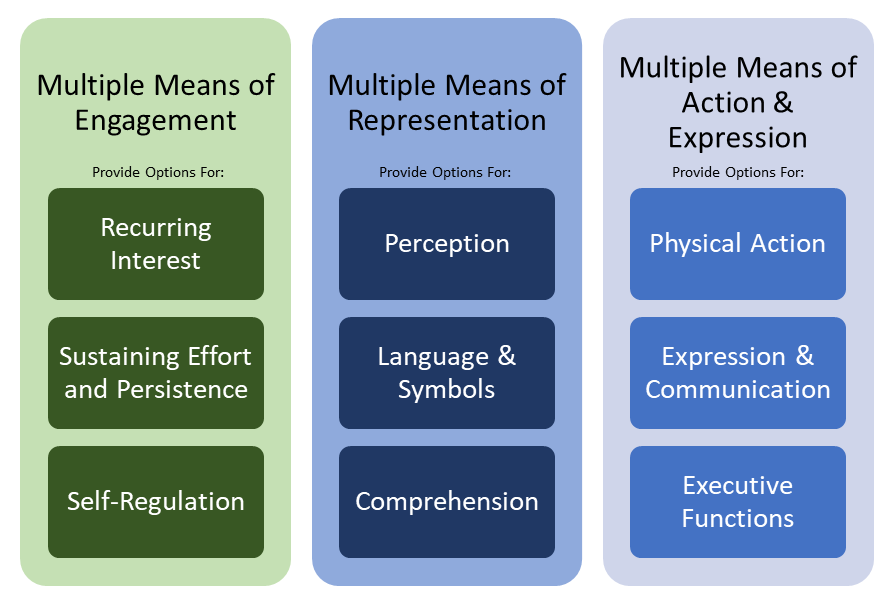

Learner diversity has become the norm, rather than the exception, and thus curriculum designers must incorporate classroom delivery and assessment in a way that will optimize the capacity to learn for all. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a scientifically based framework for developing curricula that support diverse learners. The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) asserts that UDL is based on brain-structure research, which incorporates multiple means of instruction, action, and expression, and engagement (CAST, 2011), and was developed to identify and address student diversity within the classroom (Doran, 2015).

UDL was originally established as a sustainable pedagogical framework to enhance the inclusion of students with disabilities in post-secondary classrooms, and there is a distinct lack of research on the use of UDL within the context of CDL learners in higher education (Fovet, 2019, 2020). However, CAST (CAST, 2011) now maintains that UDL has relevance for students of all profiles, not just learners with disabilities. Fovet (2019) purports that as the UDL framework has an intentional focus on the user experience, without relying on medical model perspectives, it has also shown significant promise regarding the inclusion of international students, Indigenous students, and first-generation students.

Similarly, Rao, (2015) notes that UDL can provide supports that are useful for CLD students who are learning a second language and are assimilating to new cultural systems and educational expectations. Bradshaw (2020) suggests that UDL can benefit students with identifiable and unidentifiable disabilities and suggests that some of these “hidden” disabilities include perceptual and language challenges. Using UDL as an instructional design framework, educators can proactively assess, address, and support learner variability, and reduce barriers for students in higher education environments (Evmenova et al, 2024).

Practical Implementation of UDL Practices for CDL Learners

Designing courses that support linguistically diverse learners in higher education involves thoughtful consideration of how content is presented, and assessed, and the interactions within the course content and structure. This can include incorporating best practices in course design, affording faculty flexibility in providing alternatives and options for interactions and assessments, and professional development for faculty and teaching staff to best support learning in these students.

Designing courses that support linguistically diverse learners in higher education involves thoughtful consideration of how content is presented, and assessed, and the interactions within the course content and structure. This can include incorporating best practices in course design, affording faculty flexibility in providing alternatives and options for interactions and assessments, and professional development for faculty and teaching staff to best support learning in these students.

A myriad of authors provides classroom-based suggestions for best meeting accessibility standards for CDL students, including using clear and simple language in course materials and instructions, providing lecture notes or slides in advance, multimodal content delivery, offering language support resources, promoting peer interaction and support, and pairing linguistically diverse learners with native speakers (Cumming & Rose, 2022; Doran, 2015; Gronseth et al, 2021; Rao, 2015, 2019; Ralabate & Nelson, 2017; Saha-Gupta et al, 2019). Utilizing technology and accessibility tools can support linguistically diverse learners as well, for example, by providing transcripts or captions for audiovisual materials, using bilingual dictionaries or translation tools, and ensuring that online platforms are accessible and user-friendly for students of varying language backgrounds (Doran, 2015; Ralabate & Nelson, 2017). Instructors can commit to providing timely feedback and clarification, develop and offer alternative assessment methods, and afford flexibility in assignments and activities. Institutions should offer training and professional development opportunities for faculty and teaching staff on effective strategies for supporting CLD learners. This includes understanding the challenges these students face and designing and implementing inclusive teaching practices to address these challenges and enhance learning outcomes (Doran, 2015; Ralabate & Nelson, 2017).

Has UDL Solved Accessibility Issues for All Learners?

In North America, there has been early pressure through legislation to improve accessibility measures for students with disabilities (Fovet, 2019); diverse learners within other areas have not received the same attention, and inclusive provisions for CDL students are considered best practices but do not represent a legal obligation. While the benefits of UDL in higher education have become increasingly obvious, the push for UDL implementation has nonetheless slowed in many ways. In the realm of higher education, UDL-related research is somewhat limited and hampered by competing definitions, resources, goals, and constructs (Fornauf & Erickson, 2020). Student outcomes are invariably considered a gold standard of success of the implementation of new processes and procedures, and yet, Capp’s (2017) metanalysis cites that UDL, while an effective teaching methodology for all students, has an impact on educational outcomes that could not be demonstrated.

In North America, there has been early pressure through legislation to improve accessibility measures for students with disabilities (Fovet, 2019); diverse learners within other areas have not received the same attention, and inclusive provisions for CDL students are considered best practices but do not represent a legal obligation. While the benefits of UDL in higher education have become increasingly obvious, the push for UDL implementation has nonetheless slowed in many ways. In the realm of higher education, UDL-related research is somewhat limited and hampered by competing definitions, resources, goals, and constructs (Fornauf & Erickson, 2020). Student outcomes are invariably considered a gold standard of success of the implementation of new processes and procedures, and yet, Capp’s (2017) metanalysis cites that UDL, while an effective teaching methodology for all students, has an impact on educational outcomes that could not be demonstrated.

A common methodology to meet UDL standards for linguistically diverse students is to provide captioning. In a study from Venturi et al (2022), in the context of a UDL-designed classroom, the captions provided were found to benefit learners only if their English language proficiency was high enough; when language proficiency was poor, however, the captions were detrimental, and performance was worse than having no captions. The authors caution that institutions with a commitment to UDL understand that not one type of caption suits all, and highly recommend testing captioning systems with diverse learners, to better understand what factors are beneficial for whom and when.

Appropriate training and supervision in the implementation of UDL are key to its efficacy. In a review of current literature on the application of UDL as an accessibility tool for higher education, Cumming and Rose (2022) found that instructors implementing UDL principles in coursework reported that UDL improved their teaching; however, it was also noted students perceived UDL elements to be more useful than faculty members, and that a key barrier to UDL efficacy was instructor attitudes. Evmenova (2014) notes that while all the participant instructors recognized the value of UDL and were eager to implement it in their learning environments, they also strongly recommended additional professional development on the UDL framework and specific technologies. In Kennette and Wilson’s (2019) comparative study, the literature cites a need for appropriate staff training and awareness of the advantages of UDL for it to be beneficial to students. While instructors who were aware of student needs reported that they wanted more training, and responded positively, those who felt that they did not have enough information on student needs, undervalued UDL frameworks and were more likely to believe students with accommodations had unfair advantages (Black et al, 2015).

With regard to curriculum development, Gronseth et al (2021) note that course designers and instructors can be self-referential, reflecting their own needs, experiences, and preferences in their designs rather than factoring in those of the learners themselves. Institutions should offer training and professional development opportunities for faculty and teaching staff on effective strategies for supporting linguistically diverse learners, including an understanding of challenges faced by these students and implementing inclusive teaching practices to enhance learning outcomes.

Conclusion

With the significant increases in enrollment of international students over the past decade, the diversity found among Canadian students in higher education is expanding exponentially. With this growth, comes a broad spectrum of challenges for these institutions, in the attempt to meet the unique needs and provide inclusive and accessible learning to students who have an inherently high degree of variability of individual preferences, abilities, and lived experiences. When physical barriers and classroom accommodations are the focus of inclusiveness, students with cultural and linguistic diversity are often excluded from discourse involving accessibility issues. These students face substantial challenges, especially with regard to accessibility matters directly related to curricula, delivery, and evaluation methodologies. By framing these issues of CDL learners within the lens of accessibility and course design, higher education institutions can better address the needs of linguistically diverse learners, promote equity in education, and create environments where all students can thrive academically and socially. Providing resources, instructor training, and policy development and potentially legislation around the standardized application of Universal Design for Learning frameworks in this respect may help to mitigate the pedagogical barriers faced by culturally and linguistically diverse students. Regardless of the approach, it is clear that educators and scholars must continue to strive to transform curricula and methodologies across campuses to effectively address the diverse essential needs of all learners. We are not there (yet!)

References

Altbach, P., & Knight, J. (2007). Internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3/4), 290–305.

Black, R. D., Weinberg, L. A., & Brodwin, M. G. (2014). Universal Design for instruction and learning: A pilot study of faculty instructional methods and attitudes related to students with disabilities in higher education. Exceptionality Education International, 24(1), 48–64.

Bradshaw, D. G. (2020). Examining beliefs and practices of students with hidden disabilities and universal design for learning in institutions of higher education. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 20(15).

Campbell, D. (2022). Experts on accessibility, ableism and inclusion across Canada gather for second National Dialogues and Action. https://utsc.utoronto.ca/news-events/university-news/experts-accessibility-ableism-and-inclusion-across-canada-gather-second-national

Capp, M. J. (2017). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(8), 791-807.

CAST (n.d.). UDL ON CAMPUS: Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education. http://udloncampus.cast.org/home

CAST (2011). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.0. http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines

Cumming, T. M., & Rose, M. C. (2022). Exploring universal design for learning as an accessibility tool in higher education: A review of the current literature. The Australian Educational Researcher, 49(5), 1025-1043.

Doran, P. R. (2015). Language accessibility in the classroom: How UDL can promote success for linguistically diverse learners. Exceptionality Education International, 25(3).

EduCanada (n.d.). International student wellness. https://www.educanada.ca/study-plan-etudes/during-pendant/wellness-bien-etre.aspx?lang=eng

Erudera (2023). Canada International Student Statistics. https://erudera.com/statistics/canada/canada-international-student-statistics/

Evmenova, A. S., Hollingshead, A., Lowrey, K. A., Rao, K., & Williams, L. D. (2024). Designing for Diversity and Inclusion: UDL-Based Strategies for College Courses (Practice Brief). Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 37(1).

Evmenova, A. (2018). Preparing teachers to use universal design for learning to support diverse learners. Journal of Online Learning Research, 4(2), 147-171.

Fornauf, B. S., & Erickson, J. D. (2020). Toward an inclusive pedagogy through universal design for learning in higher education: A review of the literature. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2), 183-199.

Fovet, F. (2020). Universal design for learning as a tool for inclusion in the higher education classroom: Tips for the next decade of implementation. Education Journal, 9(6), 163-172.

Fovet, F. (2019). Not just about disability: Getting traction for UDL implementation with international students. In Transforming Higher Education Through Universal Design for Learning (pp. 179- 200). Routledge.

Gronseth, S. L., Michela, E., & Ugwu, L. O. (2021). Designing for Diverse Learners. In J. K. McDonald & R. E. West (Eds.), Design for Learning: Principles, Processes, and Praxis. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/id/designing_for_diverse_learners

Haug, P. (2017). Understanding inclusive education: ideals and reality. Scandinavian journal of disability research, 19(3), 206-217.

Kennette, L., & Wilson, N. (2019). Universal Design for Learning (UDL): Student and faculty perceptions. Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education, 1(2), 1–26.

Kumar, K. L., & Wideman, M. (2014). Accessible by design: Applying UDL principles in a first-year undergraduate course. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(1), 125-147.

Lanthier, S., Tishcoff, R., Gordon, S., and Colyar, J. (2023). Accessibility Services at Ontario Colleges and Universities: Trends, Challenges and Recommendations for Government Funding Strategies. https://heqco.ca/pub/accessibility-services-at-ontario-colleges-and-universities- trends- challenges-and-recommendations-for-government-funding-strategies/

Mohler, E.M., Godin-Jacques, C. (2023). NEADS State of the Schools Report: Report on the State of Canadian Post-Secondary Education and Accessibility. https://disabilityawards.ca/wp- content/uploads/2024/01/NEADS-State-of-the-Schools-Report- September-2023.docx.

Ontario Human Rights Commission (n.d.). Post-secondary education. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/opportunity-succeed-achieving-barrier-free-education-students- disabilities/post-secondary-education

Ralabate, P., & Nelson, L. L. (2017). Culturally responsive design for English learners: the UDL approach. CAST Professional Publishing.

Rao, K. (2015). Universal design for learning and multimedia technology: Supporting culturally and linguistically diverse students. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 24(2), 121- 137.

Rao, K. (2019). Instructional design with UDL: Addressing learner variability in college courses. In Transforming higher education through universal design for learning (pp. 115-130). Routledge.

Robertson, S. L. (2010). Challenges facing universities in a globalising world. Bristol: Centre for Globalisation, Education and Societies. http://susan leerobertson.com/publications/

Saha-Gupta, N., Song, H., & Todd, R. L. (2019). Universal design for learning (UDL) as facilitating access to higher education. Journal of Education and Social Development, 3(2), 5-9.

Statista. (2022). https://www.statista.com/statistics/788155/international-student- share-of- higher-education-worldwide/

Statistics Canada (2023). Table 37-10-0163-01 Postsecondary enrolments, by International Standard Classification of Education, institution type, Classification of Instructional Programs, STEM and BHASE groupings, status of student in Canada, age group and gender DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/3710016301-eng

Statistics Canada. (2024). Is the recent spike in international students affecting domestic university enrolment at Canadian public postsecondary institutions? https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/5435-recent-spike-international-students-affecting-domestic-university-enrolment-canadian

Transition Resource Guide. (n.d.). Accessibility Services. https://www.transitionresourceguide.ca/learn-about-accessibility/accessibility-services

Venturini, S., Vann, M. M., Pucci, M., & Bencini, G. M. (2022). Towards a More Inclusive Learning Environment: The Importance of Providing Captions That Are Suited to Learners’ Language Proficiency in the UDL Classroom. In Transforming our World through Universal Design for Human Development (pp. 533-540). IOS Press.

Ward, H. C., & Selvester, P. M. (2012). Faculty learning communities: improving teaching in higher education. Educational Studies, 38(1), 111-121.