Nonverbal Communication Supports for an Inclusive Classroom

Leslie Sumner

Introduction

Over the last decade, a significant technological increase has impacted society considerably. One of these impacts is the mortality rates of children in Canada; with advanced medical technology, many children are living longer but are also living with profound disabilities (O’Neil, 2024). This influx of children with disabilities also impacts our education system and has caused unique accessibility issues. One of these accessibility issues is students with limited communication abilities (non-verbal students). In this paper, I will focus on students with physical or neuromuscular issues that impair communication by limiting speech and physical movement but not cognitive function. In a research project from 2016, 71% of families agreed that a barrier for their child was finding knowledgeable staff and resources (Ferenczy & van Schouwen, 2016). With little change to the foundation of the Ontario education system combined with the influx of students with disabilities, the system is struggling to support all students, especially non-verbal students, in mainstream classes. Many educators find it difficult to believe that students with complex needs can or need to learn like their peers. Presuming intelligence for all students is essential, but biased opinions can hinder teachers’ inclusive practices. These biases must be addressed, as they can hinder the progress towards a more inclusive education system. Students with disabilities face discrimination and ableist attitudes, which undermine their ability to get the educational resources needed to assist them in achieving high levels of academics. Once these biases are addressed, work can be done to ensure more equitable practices in our education system. Educators need a better understanding of inclusive instructional design and technology to ensure that non-verbal students can access the curriculum alongside their classmates.

First Step

As a teacher and mother of a non-verbal child, I have encountered resistance at all levels within the public school system. My son’s first experience in a public school was meeting his kindergarten teacher; her first question was, “Aren’t there schools for kids like him?”. This is the type of ableist attitude held by many mainstream public school teachers. High-needs students are seen as burdens and take attention and resources away from other students (Rose, 2000). Teachers must stop viewing students with disabilities as people who need to be fixed or accommodated so they can access education like ‘normal’ students (Rose, 2000), and they must see them as students who have abilities that need to be celebrated. Anti-ableist training is an essential starting place to help promote awareness and increase empathy and advocacy among educators (Nieminen, 2022). Without this training, making positive strides towards an inclusive public education system will not be easy. Anti-ableist training for educators can help teachers recognize their prejudices, encouraging empathy (Nieminen, 2022) and, in turn, help them understand the importance of changing their teaching pedagogy. School efficacy is essential and can be accomplished if teachers feel confident to share their knowledge to support inclusive pedagogy. A robust, positive learning community that celebrates the sharing of authentic practices for non-verbal learners lessens the burden on a single educator. Anti-ableist training is an essential foundation for teachers, helping them understand the need to embrace systemic educational changes and ensuring all students are supported and celebrated for their differences.

Instructional Design

Making a classroom equitable for all students can seem unattainable for classroom teachers, especially with class sizes upward of 30 students and many of those students with individual education plans (IEPs). Many standard school practices, like curriculum delivery and assessment, are inherently discriminatory (Nieminen, 2022). The standard lecture and ability for students to raise their hands and ask questions is a skill many physically disabled non-verbal students can not participate in, making this a practice that can discriminate against students. Most forms of assessment, like exams, standardized testing, essay writing, or presentations, are also familiar educational practices that can discriminate against students with disabilities (Nieminen, 2022). Public schools are traditionally assessment and output-focused, emphasizing programming for the average student. Ontario’s public education’s main principle is improving all students’ learning (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2010). However, many standard common practices are rooted in prominent discriminatory practices that inherently do not support all students, especially students with unique learning disabilities, like communication impairments.

Making a classroom equitable for all students can seem unattainable for classroom teachers, especially with class sizes upward of 30 students and many of those students with individual education plans (IEPs). Many standard school practices, like curriculum delivery and assessment, are inherently discriminatory (Nieminen, 2022). The standard lecture and ability for students to raise their hands and ask questions is a skill many physically disabled non-verbal students can not participate in, making this a practice that can discriminate against students. Most forms of assessment, like exams, standardized testing, essay writing, or presentations, are also familiar educational practices that can discriminate against students with disabilities (Nieminen, 2022). Public schools are traditionally assessment and output-focused, emphasizing programming for the average student. Ontario’s public education’s main principle is improving all students’ learning (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2010). However, many standard common practices are rooted in prominent discriminatory practices that inherently do not support all students, especially students with unique learning disabilities, like communication impairments.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

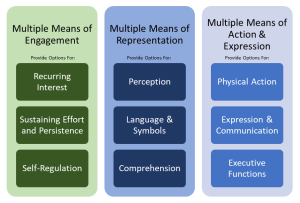

Two guiding educational documents in Ontario are Growing Success: Assessment, Evaluation, and Reporting in Ontario (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2010) and Learning for All: A Guide to Effective Assessment and Instruction for All Students (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2013). Both enforce the importance of equitable education practices. Even though they are over a decade old, these documents have value with their focus on Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL helps teachers overcome the extra classroom burdens, especially around individual programming, by using an inclusive approach to designing curriculum, including assessment (CAST, 2018). The UDL framework is recognized by the education system in Ontario as one of the three practical approaches to learning outlined in the provincial document Learning for All (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2013). This forward-thinking approach to programming can be intimidating for teachers because it is less structured and allows for student choices at all stages: what they want to learn, how they want to learn, and the final output to show learning (CAST, 2013). UDL looks at the ‘big idea’ of curriculum, allowing flexibility that helps to promote a more inclusive environment (Rose, 2000). This programming style does not remove all individual programming, but it can help overcome many issues, allowing the teachers to focus on specific needs for more complex disabilities. UDL shifts the teacher’s role from a curriculum deliverer to a facilitator who guides students’ learning, which can also reduce the burden teachers feel when accommodating multiple complex students. UDL’s strength is focusing on the student’s differences as a starting place for curriculum building and celebrating those differences instead of trying to fit student diversity into normative standards. CAST, a leader in guidelines and promotion of UDL, outlines that students need multiple means of engagement (motivation), representation (introducing, guiding information), and actions or outcomes (goal-oriented strategies); this is fundamental for a nonverbal student. Allowing students to participate in their programming at all three stages can also help reduce the overall struggle for teachers and empower students to have control of their education. This mindset shifts from teacher-focused to student-focused, strips away the biases of the leader, and can promote diversity among learners. All students can benefit from this type of classroom design, but allowing for learning diversity is highly beneficial for students who struggle with communication impairments; multiple avenues to access information can be crucial, especially while you figure out best practices for individuals.

Two guiding educational documents in Ontario are Growing Success: Assessment, Evaluation, and Reporting in Ontario (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2010) and Learning for All: A Guide to Effective Assessment and Instruction for All Students (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2013). Both enforce the importance of equitable education practices. Even though they are over a decade old, these documents have value with their focus on Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL helps teachers overcome the extra classroom burdens, especially around individual programming, by using an inclusive approach to designing curriculum, including assessment (CAST, 2018). The UDL framework is recognized by the education system in Ontario as one of the three practical approaches to learning outlined in the provincial document Learning for All (King’s Printer for Ontario, 2013). This forward-thinking approach to programming can be intimidating for teachers because it is less structured and allows for student choices at all stages: what they want to learn, how they want to learn, and the final output to show learning (CAST, 2013). UDL looks at the ‘big idea’ of curriculum, allowing flexibility that helps to promote a more inclusive environment (Rose, 2000). This programming style does not remove all individual programming, but it can help overcome many issues, allowing the teachers to focus on specific needs for more complex disabilities. UDL shifts the teacher’s role from a curriculum deliverer to a facilitator who guides students’ learning, which can also reduce the burden teachers feel when accommodating multiple complex students. UDL’s strength is focusing on the student’s differences as a starting place for curriculum building and celebrating those differences instead of trying to fit student diversity into normative standards. CAST, a leader in guidelines and promotion of UDL, outlines that students need multiple means of engagement (motivation), representation (introducing, guiding information), and actions or outcomes (goal-oriented strategies); this is fundamental for a nonverbal student. Allowing students to participate in their programming at all three stages can also help reduce the overall struggle for teachers and empower students to have control of their education. This mindset shifts from teacher-focused to student-focused, strips away the biases of the leader, and can promote diversity among learners. All students can benefit from this type of classroom design, but allowing for learning diversity is highly beneficial for students who struggle with communication impairments; multiple avenues to access information can be crucial, especially while you figure out best practices for individuals.

Assessment

Assessment is an area in which non-verbal students are discriminated against regularly. Many assessments used in classrooms are not accessible to non-verbal students, especially when there are other medical complexities. Using these exclusive practices in your classroom, knowing a student can not access the material, is the definition of discrimination (Tai et al., 2022). Ungrading, the practice of not giving a formal grade to learning but instead focusing on the learner and using timely feedback to promote learning, would remove the inherently discriminatory practice and facilitate learning (Blum, 2023), especially for non-verbal students. Ungrading is controversial for many educators, but evidence supports inclusion and autonomy (Blum, 2023). Educating teachers on the benefits of changing their grading system by informing them of the discrimination traditional grading can cause could be another positive aspect of anti-ableist education. Assessment is essential for learning, but if it is a discriminatory practice, how can it be valid or have academic integrity (Tai et al., 2022)? Understanding how a standard common practice is exclusive should help motivate educators to try something new for the benefit of their students.

Assessment is an area in which non-verbal students are discriminated against regularly. Many assessments used in classrooms are not accessible to non-verbal students, especially when there are other medical complexities. Using these exclusive practices in your classroom, knowing a student can not access the material, is the definition of discrimination (Tai et al., 2022). Ungrading, the practice of not giving a formal grade to learning but instead focusing on the learner and using timely feedback to promote learning, would remove the inherently discriminatory practice and facilitate learning (Blum, 2023), especially for non-verbal students. Ungrading is controversial for many educators, but evidence supports inclusion and autonomy (Blum, 2023). Educating teachers on the benefits of changing their grading system by informing them of the discrimination traditional grading can cause could be another positive aspect of anti-ableist education. Assessment is essential for learning, but if it is a discriminatory practice, how can it be valid or have academic integrity (Tai et al., 2022)? Understanding how a standard common practice is exclusive should help motivate educators to try something new for the benefit of their students.

Like UDL, assessment for inclusion (AFI) observes the diversity of individuals first and produces evaluations that can be accessed without extensive accommodation (Nieminen, 2022). Rethinking how, what, and for whom you assess can help remove biases and celebrate human diversity. This approach is unfamiliar to many educators and can be intimidating to put into practice. Embracing partnerships with all students and encouraging them to be actively involved in their assessment can reduce the stress for educators and support a better learning environment.

Assessment for Engagement

As an educator for over 25 years, I have worked with students with high needs for many years and have struggled with constructive assessments for my students. An idea I have pondered is assessment for engagement. Assessing students on their level of engagement in a subject could be an inclusive way to evaluate diverse students. This universal practice could support a diverse and inclusive classroom for all students, including non-verbal students. What would assessment for engagement look like? Students would be assessed on their engagement in a subject. A higher grade would mean the student is more engaged in the subject; a lower grade would be less engaged. Neither a high nor low grade indicates a pass or fail; it is just how motivated or interested a student is in a particular area. Students with a similar engagement in a subject, regardless of their academic level, could contribute positively to a course. There are many unanswered questions when trying something new. However, the education system, as it is, is not promoting diversity for all students, so without alternatives, no systemic changes can happen.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

So far, I have talked about instructional design, which would benefit all students and make our education system more inclusive, which also supports non-verbal students. Now, I am going to focus on support specific to communication disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is essential for working with non-verbal students. AAC includes everything a person can access besides talking to communicate, including facial expressions, body movement, picture communication system (PCS), and technology. Understanding an individual’s communication style takes time and practice. Education and specific training are essential to become a productive communication partner. Educators should familiarize themselves with all forms of communication a student may use and model that form of language while teaching. Modeling allows others to understand how to communicate with that student, allows the student to feel included, and teaches them how to communicate what they are learning (Kleinert, 2022).

So far, I have talked about instructional design, which would benefit all students and make our education system more inclusive, which also supports non-verbal students. Now, I am going to focus on support specific to communication disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is essential for working with non-verbal students. AAC includes everything a person can access besides talking to communicate, including facial expressions, body movement, picture communication system (PCS), and technology. Understanding an individual’s communication style takes time and practice. Education and specific training are essential to become a productive communication partner. Educators should familiarize themselves with all forms of communication a student may use and model that form of language while teaching. Modeling allows others to understand how to communicate with that student, allows the student to feel included, and teaches them how to communicate what they are learning (Kleinert, 2022).

Eye-Gaze Technology

![]() Tobii Dynavox (2024) is a leader in eye gaze technology, with capabilities on a PC and, recently, the iPad, coupled with apps like TD Snap, Word Prediction, and Gaze Viewer; this technology opens doors for authentic communication for non-verbal students. Eye gaze technology uses an infrared camera; the camera can track a person’s eye movement on the computer screen and translate those movements to the computer, acting like a hand-controlled computer mouse. Although very expensive, this technology can be funded in Ontario through the Centralized Equipment Pool if a person qualifies. There are many apps for communication; TD Snap is one example that is user-friendly and supports a robust touch screen (or eye gaze controlled) communication system for people at all different communication levels. Programs like Gaze View can help record and track communication and can be used for multiple purposes. As an educator, I know it can be an excellent resource for assessment.

Tobii Dynavox (2024) is a leader in eye gaze technology, with capabilities on a PC and, recently, the iPad, coupled with apps like TD Snap, Word Prediction, and Gaze Viewer; this technology opens doors for authentic communication for non-verbal students. Eye gaze technology uses an infrared camera; the camera can track a person’s eye movement on the computer screen and translate those movements to the computer, acting like a hand-controlled computer mouse. Although very expensive, this technology can be funded in Ontario through the Centralized Equipment Pool if a person qualifies. There are many apps for communication; TD Snap is one example that is user-friendly and supports a robust touch screen (or eye gaze controlled) communication system for people at all different communication levels. Programs like Gaze View can help record and track communication and can be used for multiple purposes. As an educator, I know it can be an excellent resource for assessment.

For technology to be helpful, school staff need training in technology and instruction on how to be good communication partners to help students reach their potential. Educators need to understand the need for clean and simple language, large targets, and uncluttered assignments to allow for the optimal ability of eye gaze. Although complex technology can be highly liberating to students, it is challenging and takes much practice for even simple conversation. Without well-informed educators helping students become proficient with this technology, it could lead to frustration and even more communication issues.

Resources for non-verbal students, specifically eye gaze users, are difficult to find. Susan Norwell, M.A. in Special Education, with over 25 years of experience and co-founder at Rhett University, is well known for her remarkable materials and educational strategies for nonverbal students (2020). She has numerous courses to aid students in academic settings, focusing on literacy and communication. The Rhett University website is an accessible resource and a convenient starting place for professional development for educators. Using outside sources to build efficacy in the school setting needs to be promoted when new technology and skill sets are outside the scope of the specialists within a school board.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI)

Brain-computer interface (BCI) has the potential to be another future technology that could play a critical role in augmentative and alternation communication (AAC). BCI allows electrical signals from the brain to be linked to a computer. Once the computer learns these electrical pathways, it can be translated into a functional command (Kinney-Lane et al., 2020). For example, if a person thinks about the word yes, the computer can learn the electrical pathway to recognize that thought pathway as the word yes and, in turn, display the word. The research on this technology has been primarily with adults. However, researchers are seeing the need to focus on pediatrics (Kinney-Lane et al., 2020). BCI is a long way from becoming functional or affordable. However, with the push for pediatrics research, this may be another way to help non-verbal students find authentic communication methods.

Brain-computer interface (BCI) has the potential to be another future technology that could play a critical role in augmentative and alternation communication (AAC). BCI allows electrical signals from the brain to be linked to a computer. Once the computer learns these electrical pathways, it can be translated into a functional command (Kinney-Lane et al., 2020). For example, if a person thinks about the word yes, the computer can learn the electrical pathway to recognize that thought pathway as the word yes and, in turn, display the word. The research on this technology has been primarily with adults. However, researchers are seeing the need to focus on pediatrics (Kinney-Lane et al., 2020). BCI is a long way from becoming functional or affordable. However, with the push for pediatrics research, this may be another way to help non-verbal students find authentic communication methods.

Conclusion

Non-verbal students are a unique group who deserve access to education like their classmates. Their diversity should be celebrated and not seen as a teacher’s burden that detracts from the ‘normal’ student’s resources. Anti-ableist training is an essential first start for teachers to learn empathy and advocacy skills to motivate themselves to find the resources and training they need to promote an inclusive classroom. Many inclusive strategies, like instructional design and technologies, can facilitate an inclusive classroom where no student is seen as a burden and potentially decrease the teacher’s workload. Ontario government documents support these ideas. However, many teachers believe it is not their responsibility to support complex students without the resources and training, and they do not need an inclusive classroom; accommodation for individual students is enough. However, are accommodations sufficient to make a practice inclusive, or does this also continue to promote exclusion? Teachers must embrace change, especially if their practices exclude the diversity that should be encouraged in their classrooms. Teachers need to be given the opportunities to learn about universal design for learning and be supported while transitioning from traditional lesson planning to ensure an inclusive classroom can be established. Finding a core group of teachers who promote change, support each other, and encourage efficacy at the school level is essential to ensuring that all students can be supported.

Students with non-verbal communication issues need individualized support. Augmentative and alternative communication resources can be unfamiliar to teachers, but with education, they can become communication partners and model language used by non-verbal students. Understanding the complexity of eye gaze technology and being open to future technologies like brain-computer interfaces could be life-changing for students. However, I believe the key to inclusive education is for the teacher first to understand their biases and non-inclusive practices and their ability to advocate for change. Change is difficult, but if educators can step into their complex students’ shoes and be as vulnerable as they are, this will build empathy and a sense of community that can celebrate diversity.

References

Blum, S. D. (2024, May 3). Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). West Virginia University Press. https://wvupressonline.com/ungrading

CAST. (2024, May 14). The UDL guidelines. UDL. http://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Ferenczy, M., & van Schouwen, J. (2016, June). Access to special education in Ontario in a social justice context. ldao. https://www.ldao.ca/wp-content/uploads/Access_to_Special_Education_in_Ontario_in_a_Social_Justice_Context_June-2016.pdf

King’s Printer of Ontario (2010). Growing success assessment, evaluation and reporting in Ontario schools (2010). [PDF file]. https://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/growsuccess.pdf

King’s Printer for Ontario (2013). Learning for All: A Guide to Effective Assessment and Instruction for All Students, Kindergarten to Grade 12. [PDF file]. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-learning-for-all-2013-en-2022-01-28.pdf

Kinney-Lang, E., Kelly, D., Floreani, E. D., Jadavji, Z., Rowley, D., Zewdie, E. T., Anaraki, J. R., Bahari, H., Beckers, K., Castelane, K., Crawford, L., House, S., Rauh, C. A., Michaud, A., Mussi, M., Silver, J., Tuck, C., Adams, K., Andersen, J., … Kirton, A. (2020, November 10). Advancing brain-computer interface applications for severely disabled children through a multidisciplinary national network: Summary of the inaugural Pediatric BCI Canada meeting. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2020.593883/full

Kleinert, H. L., Kearns, J., Land, L.-A., L. Page, J., & Kleinert, J. O. (2022). Peer-assisted aided AAC modeling for students with complex communication needs. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 55(4), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/00400599221122871

Nieminen, J. H. (2022). Assessment for Inclusion: Rethinking Inclusive Assessment in Higher Education. Teaching in Higher Education, 29(4), 841–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.2021395

O’Neill, A. (2024, July 4). Canada: Child mortality rate 1830-2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1041751/canada-all-time-child-mortality-rate

Online training courses. Rett University. (2024, January 3). https://rettuniversity.org//online-training-courses/

Rose, D. (2000). Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 15(2), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264340001500208

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2022). Assessment for Inclusion: Rethinking Contemporary Strategies in Assessment Design. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(2), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451

Tobii Dynavox CA. (2024). All products. https://ca.tobiidynavox.com/pages/products

Wikimedia Commons (2020, August 30). Sample_page_from_AAC_communication_book. [Image file]. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c3/Sample_page_from_AAC_communication_book.png