36

ACR – Neurologic – Headache

Case

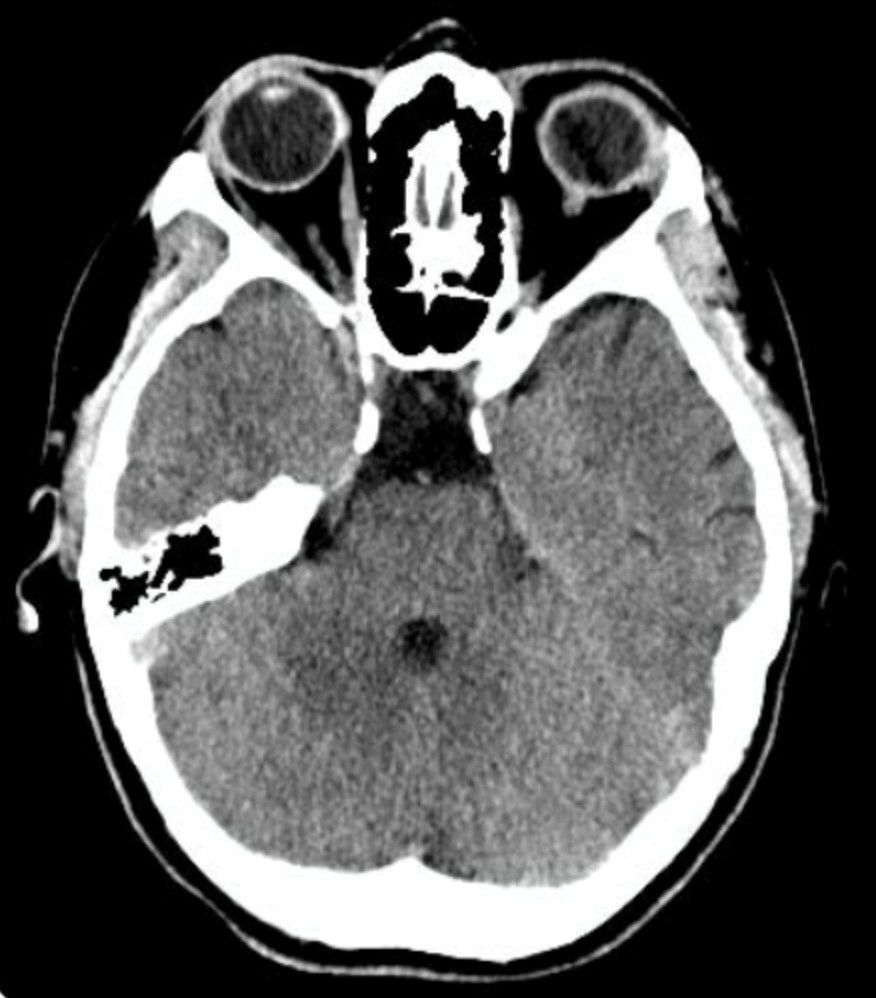

Aqueductal Stenosis, Obstructive Hydrocephalus

Clinical:

History – Nausea, vomiting, headache.

Symptoms – Headache.

Physical – The patient had possible papilledema. No focal neurologic abnormalities.

DDx:

Brain Tumor

Hydrocephalus

Meningitis

Imaging Recommendation

ACR – Neurologic – Headache – Focal Neurologic Deficit or Papilledema, Variant 13

MR of the Head without IV contrast – if not available, or contraindicated, CT is the next best examination

CT of the Head without IV contrast

Imaging Assessment

Findings:

The ventricles cranial to the cerebral aqueduct were dilated. The aqueduct became non-visible downstream in the brainstem. The fourth ventricle was not enlarged. Ne evidence of a mass or extrinsic lesion.

Interpretation:

Probable aqueductal stenosis. MR of the brains was recommended to assess for subtle intra or extra-ventricular causes for aqueductal stenosis.

Diagnosis:

Aqueductal Stenosis, Hydrocephalus

Discussion:

Headache is a cardinal symptom of increased intracranial pressure and is frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which is usually worst in the mornings. In the setting of headache, the presence of bilateral papilledema indicates increased intracranial pressure that is transmitted to the optic nerve sheath. As such, the differential diagnosis for headache in the setting of papilledema is quite broad. It includes any mass such as, abscess, primary or metastatic tumors, hematoma, cerebral edema, communicating or obstructive hydrocephalus, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), dural venous sinus thrombosis, and entities that result in increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production. MRI of the head with and without contrast is the imaging study of choice. CT of the head with contrast may be appropriate if MRI is contraindicated or not available.

The cause, or type of, the patient’s headache should be evaluated by procuring a careful history and performing a physical examination while focusing on detecting any warning signals that would prompt further diagnostic testing. In the absence of worrisome features in the history or examination, the task is then to diagnose the primary headache syndrome based on the clinical features.

If atypical clinical features are present, or the patient does not respond to conventional therapy, the possibility of a secondary headache disorder should be investigated.

When considering such a common disorder as headache, indications for imaging use become relevant. This is particularly true in the face of emerging and rapidly evolving technologies in use today. Performing low-yield studies is likely to result in false-positive results, with the consequent risk of additional and unnecessary procedures. Additionally, the cost to the healthcare system must be considered related to imaging. The yield of positive studies in patients referred with isolated, non-traumatic headache is approximately 0.4%. Assuming the cost of a CT scan is $400, and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is $900, the cost to detect a lesion is $100,000 with CT and $225,000 with MRI.

One should not assume, however, that there is no social benefit in negative imaging studies in the setting of headache. Indeed, headache symptoms can be quite ominous and onerous, and there can be tremendous costs with respect to loss of productivity and quality-of-life.

Imaging findings of Hydrocephalus:

- Hydrocephalus is defined as an expansion of the ventricular system on the basis of an increase in the volume of cerebrospinal fluid contained within it.

- In hydrocephalus the ventricles are usually disproportionately dilated when compared with the sulci, whereas both the ventricles and sulci are proportionately enlarged in cerebral atrophy.

- The temporal horns are particularly sensitive to increases in CSF pressure. In the absence of hydrocephalus, the temporal horns are barely visible. With hydrocephalus the temporal horns may be greater than 2 mm in size.

- Acute hydrocephalus may result in peri-ventricular edema in the white matter.

- Two major subtypes: Communicating and Non-communicating hydrocephalus.

- Intra-ventricular blood and subarachnoid blood can lead to communicating hydrocephalus.

- Classically, the 4th ventricle is dilated in communicating hydrocephalus and normal in size in non-communicating hydrocephalus.

Canadian CT Head Rules (CCHR)

Guidance for Requesting a CT Head Examination

There are several clinical guidelines that discuss when it is appropriate to order a CT Head for patients with minor trauma. These Canadian guidelines are: The Canadian CT Head Rules (CCHR), established and validated in Ottawa, Canada, the NEXUS, and the NOC, as well. It is important to know the guidelines that are being applied in your jurisdiction and use these for CT Head requests.

The Canadian CT Head Rules (CCHR) for Minor Head Injury Patients, include the following:

Minor Head Injury is:

- Minimal head injury (no loss of consciousness, amnesia, or disorientation)

The Rules are not applicable to the following:

- Age <16 years

- No clear history of trauma as the primary event

- Has a bleeding disorder or is anticoagulated

- Obvious penetrating skull injury or depressed skull fracture

- Glasgow coma scale < 13

Medium Risk of Brain Injury

- Amnesia for events before injury > or = 30 minutes

- Dangerous mechanism of injury##

Higher Risk of Brain Injury

- Glasgow Coma Scale < 15 at 2 hours after injury

- Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

- An sign of a basal skull fracture*

- Vomiting > or + = episodes

- Age > 65 years

## – Dangerous Mechanism

- Pedestrian struck by vehicle

- Occupant ejected from motor vehicle

- Fall from an elevation of > or = 3 feet or 5 stairs

* – Basal skull fracture

- Hemotympanum

- “Raccoon” eyes

- Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea or otorrhea

- Battle’s sign

Attributions

Figure 6.6A Axial CT of Head displaying a dilated Cerebral Aqueduct by Dr. Brent Burbridge MD, FRCPC, University Medical Imaging Consultants, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan is used under a CC–BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 6.6B Axial CT of Head displaying a dilated ventricles consistent with Hydrocephalus by Dr. Brent Burbridge MD, FRCPC, University Medical Imaging Consultants, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.