Hoofdstuk 16.1: Heritage as Commons: Implications for classification, design, and management

Roberto Rocco en Nicholas Clarke

Introduction

Values are at the core of design for the built environment. Values influence not only the final outcome of a design process, but also the process of design (who gets involved, how this engagement is managed, and whose voices are heard in the design process). Values also influence how spatial designs are used, preserved and managed.

Built heritage management is, after economic value, arguably the second-oldest legislated value system in the built environment. Heritage legislation, after all, aims to protect values that transcend economic, and use values. Heritage legislation often protects values in the built environment that increase over time, and therefore, age is often seen as an essential quality. The aim is to protect heritage values not for the individual, but for the common good. Over time, the focus of heritage protection has expanded from the individual monument, to the monument and its direct environment, to groups of monuments protected as an integral ensemble, to the conservation of entire cultural landscapes. [Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5]

In the Netherlands, buildings have been protected for more than a century, but the first fully-fledged legislation protecting national monuments was only adopted in 1961. This, and subsequent legislation, all prescribed values as the basis for evaluation, protection and management of historical monuments. In the current Dutch Heritage Act, a built structure, ensemble or cultural landscape can be legally protected as monument i.e. immovable property that is part of the cultural heritage, due to its beauty, significance for science, or cultural historical value (Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, 2015, Article 3.1). Earlier acts set a minimum age of 50-years for a building before it could be listed, because, it was through, that at least two generations had to pass to provide for an objective (read “scientific”) evaluation.

Other countries have their own systems of legislation and valuation, but in general they all relate to aesthetics, historical values (commemoration of past events, historical narrative or simply the passing of time) and rarity. Many countries have systems through which they subsidise the maintenance, conservation, renovation or reuse of their built heritage, because the continuation of these built environment features is thought to be in service of the community in general. Retaining and curating heritage in the built environment provides a constant in an ever increasingly fast-paced world and therefore contributes to social stability (Holden, 2018). The protection of built heritage values has greatly contributed to the maintenance and even improvement of the urban qualities of our cities, bolstering their identity and giving the inhabitants a sense of historic and contemporary belonging. The aesthetics of historic buildings and urban and rural landscapes are now of great commercial value.

However, the official valuation of built environment features was and still is often undertaken by trained experts, often raising questions about the validity of these top-down valuations. These expert opinions have long term repercussions. For instance, when an expert identifies a building as a monument, the future of that building and its environment is changed. The choices available change. A main aim for current and future generations now becomes preserving the values for which that building was protected. The same can be said for urban areas that are valued as having heritage importance. Valuing and listing can be seen as an act of design: they change the conditions in which we design. Tall buildings are often banned in protected urban areas, streets are paved to harmonize with the historic character, and, in the case of the Amsterdam Canal Zone, the bridges and quay walls are maintained in brick to keep the original atmosphere. The act of listing ‘designs’ cities over time. It also often opens up different financing possibilities to maintain a building and gives different stakeholders a stronger or weaker say in the future of the building or area.

As you can see, this is an iterative process: a process in which the outcomes influence the process, which influences the outcome and so on. The design of the built environment has a huge impact on a community’s values and identity formation and contributes to the sustainable development of those communities.

The Right to the City

It is estimated that two-thirds of the world’s people will live in urban environments by the year 2050 (Richie & Roser, 2018). One of the main questions for designers of the built environment is therefore “who does the city belong to”? The answer to this question depends a lot on the type of society in question and its societal values. Here, we will examine one possible way to answer this question: the idea of the right to the city and how this idea connects to ideas of good governance and communicative planning and design also in heritage planning and design.

The idea of the right to the city comes from the realisation, in democratic societies, that citizens have the right to influence the design of their living environments. The right to the city is the right to shape one’s living environment to one’s needs and desires (Harvey, 2008; Lefebvre, 1968). This understanding gives insight into how urban space might be understood in terms of democratic decision-making, inclusion, and stakeholder engagement. This is especially true in light of communicative theory, a very important theory for spatial planning and design, which uses ideas of public reasoning and public justification. This means that design becomes a collective, rather individual, endeavour. This idea also influences how we “design” heritage preservation.

A democratic, polycentric, and decentralised management of the city gives us the opportunity to broaden the roles of design, extending both the categorization of what is design and the range of stakeholders involved in the design process. There are important challenges ahead: most urban design processes remain in the hands of “specialists”, leaving many voices outside, but this is changing quickly. In this chapter, we explore the concept of values in design for the built environment in light of ideas like the right to the city, polycentric governance, and democracy, in the search for the just and inclusive city, a city that is designed by all its inhabitants, not just by specialists. We describe the contribution of communicative rationality theory to planning theory, in light of an innovative conceptual framework that sees design as a vehicle to achieve citizens’ right to the city. Finally, we explore what this means for heritage management, design and conservation.

But in order to be able to discuss these ideas further, we must answer the question: why do we need to plan and design heritage in an inclusive and democratic way?

Aalbers and Gibb give a wonderful summary of the concept of right to the city and its history:

“It was the French sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre who in 1968 coined the phrase ‘Le droit à la Ville’ (the right to the city) (Lefebvre, 1968, 1996). This right, to Lefebvre, has both a more abstract and a more real or concrete dimension. The abstract dimension is the right to be part of the city as an oeuvre , i.e. the right to belong to and the right to co-produce the urban spaces that are created by city dwellers, or, in other words: ‘the right not to be alienated from the spaces of everyday life (Mitchell & Villanueva, 2010, p. 667). The real dimension is a concrete claim to integrated social, political and economic rights, the right to education, work, health, leisure and accommodation in an urban context that contributes to developing people and space rather than destroying or exploiting people and space _ the right to the city is ‘like a cry and a demand’ and ‘can only be formulated as a transformed and renewed right to urban life ’ (Lefebvre, 1996, p. 158).” (Aalbers & Gibb, 2014).

Later, David Harvey redefined the right to the city as the “power to shape people’s living environment to their wishes and desires”:

“To claim the right to the city in the sense I mean it here is to claim some kind of shaping power over the processes of urbanisation, over the ways in which our cities are made and re-made and to do so in a fundamental and radical way” (Harvey, 2008).

There is a strong argument supporting the right to the city as a way to achieve a better and more inclusive city for all, which has a direct impact on how we value heritage. This argument is rooted in how common resources are better governed in a polycentric networked way.

These same realisations have been growing in the built heritage field, leading to the 2005 Council of Europe Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. The convention specifically calls for a participatory approach to the identification and curation of heritage. This means that the countries who ratify the convention commit to “foster an economic and social climate which supports participation in cultural heritage activities” including in the “identification, study, interpretation, protection, conservation and presentation” of cultural heritage (Council of Europe, 2005, Article 4).

The entire built environment is a cultural, economic and ecological heritage. The stimulus preceded by the Faro Convention calls on society to engender partnerships, and democratise decision-making in the built environment through the commons of cultural heritage.

The Governance of the City

Elinor Ostrom was an American political economist whose main body of work was dedicated to understanding the governance of the commons in different societies and cultural contexts. In 2009, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for her “analysis of economic governance, especially the commons”, which she shared with Oliver E. Williamson.

The most influential part of her work focused on how humans interact with ecosystems to keep common resources sustainable in the long term. She took special interest in how traditional (or indigenous) peoples managed their common resources and, more often than not, sustainably managed them in the long run. She noticed that traditional societies generally developed largely informal (non-written) institutional arrangements to manage natural resources and avoid resource collapse. Her work unveiled key elements of the traditional management of the commons, such as polycentric governance, symmetric communication and subsidiarity (a principle that holds that social, political, and economic issues should be dealt with at the most immediate level that is consistent with their resolution) (European Commission, 2020).

These elements mean that when decisions were taken in successful management of the commons, they usually included a variety of different perspectives and knowledge. Decisions tended to be fairer and more effective, because they included the interests of a wide range of members of the community, and their knowledge about the issues at hand. In this sense, Ostrom was suspicious of grand official schemes decided very far away from where they would have an effect. She strongly believed in the power of local decision-making that involves multiple points of view and capacities. This idea speaks to communicative theory and communicative rationality, in which communication between a diverse range of actors takes centre stage as a way to produce shared understandings about the world. In turn, these ideas speak to the idea of polycentricity in the governance of the commons.

“Polycentricity is a fundamental concept in the work of Vincent and Elinor Ostrom. The term connotes a complex form of governance with multiple centres of decision-making, each of which operates with some degree of autonomy (E. Ostrom, 2005) (V. Ostrom, Tiebout, & Warren, 1961). The decision‐making units in a polycentric governance arrangement are often described as overlapping because they are nested at multiple jurisdictional levels (e.g., local, state, and national) and also include special‐purpose governance units that cut across jurisdictions (McGinnis & Ostrom, 2011; E. Ostrom, 2005). This multilevel configuration means that governance arrangements exhibiting polycentric characteristics may be capable of striking a balance between centralized and fully decentralized or community‐based governance (Imperial, 1999)” (Carlisle & Gruby, 2019, p. 921).

There are a number of advantages to polycentric governance systems when viewed from the point of view of the governance of the city, including the incorporation of multiple perspectives that allows for a better assessment of strengths, weaknesses, threats and opportunities.

Crucially, polycentric governance, if well-managed, may increase the potential for just outcomes, especially if vulnerable groups are also represented and have their stakes recognised. Polycentric governance may also enhance “adaptive capacity, provision of good institutional fit, and mitigation of risk on account of redundant governance actors and institutions” (Carlisle & Gruby, 2019,p. 921). In sum, polycentric governance is a desirable tool for the management of the city.

The work of Ostrom is crucial because she investigates the institutions that are set up to decide upon the distribution of burdens and benefits of development. She makes a distinction between formal and informal institutions that have a role in how resources are governed, that is, how decisions are taken and who are the stakeholders involved, including the power struggles and imbalances between those stakeholders.

How does this reflect on the management of the city and heritage? We think it is clear by now that managing heritage implies the creation of shared understandings about what heritage is, how it should be used and how it should be managed by a wide range of stakeholders, not only heritage specialists. These principles are of course principles of democratic participation by all the inhabitants of a city, that is, all the members of the community that uses the resources of that city, including its heritage. This is where participatory planning and design can give us some answers.

Communicative Planning and Design

British planner Patsy Healey offers a step forward in the challenges described by Ostrom concerning polycentric governance and explains the possibilities of the communicative turn in planning for the good governance of the city, towards the “right to the city” and a “city for all”. Healey asserts that (…):

“from the recognition that we are diverse people living in complex webs of economic and social relations, within which we develop potentially very varied ways of seeing the world, of identifying our interests and values, of reasoning about them, and of thinking about our relations with others. The potential for overt conflict between us is therefore substantial, as is the chance that unwittingly we may trample on each other’s concerns. Faced with such diversity and difference, how then can we come to any agreement over what collectively experienced problems we have and what to do about them? How can we get to share in a process of working out how to coexist in shared spaces? The new wave of ideas focuses on how we get to discuss issues in the public realm.” (Healey, 1996, p. 219).

Healey correctly identifies this “new wave of planning” as having the potential to reconstruct the public realm and publicness. Communicative planning is largely based on the ideas of the German philosopher and sociologist Jürgen Habermas, the father of “communicative rationality”. Communicative rationality puts communication at the centre of human rationality. In other words, it is through communication that we shape our ideas and arguments, also in the public sphere. In fact, many thinkers believe this is the great advantage of democracy over other political systems: ideally, democracy gives space to all kinds of voices to be heard in the public arena, creating a process of “government by discussion” that is much more effective than a completely top-down form of government, like a dictatorship (Sen, 2009).

Healey recognizes the influence of Habermas in communicative planning, by positing that […]

“He [Habermas] shows us that we are not autonomous subjects competitively pursuing our individual preferences, but that our sense of ourselves and of our interests is constituted through our relations with others, through communicative practices. Our ideas about ourselves, our interests, and our values are socially constructed through our communication with others and the collaborative work this involves. If our consciousness is dialogically constructed, surely we are deeply skilled in communicative practices for listening, learning, and understanding each other. Could we not harness these capacities explicitly to the task of discussion in the public realm about issues which collectively concern us?” (Healey, 1996, p. 219).

Healey asserts that ideas of communicative rationality focus on ways of “reconstructing the meaning of a democratic practice”, based on more inclusive practices of “inclusionary argumentation”. For Healey, this is equivalent to a form of …

“…public reasoning which accepts the contributions of all members of a political community and recognises the range of ways they have of know, valuing, and giving meaning. Inclusionary argumentation as a practice thus underpins conceptions of what is being called participatory democracy (Fischer, 1990; Held, 1987) (…). Through such argumentation, a public realm is generated through which diverse issues and diverse ways of raising issues can be given attention. In such situations, as Habermas argues, the power of the ‘better argument’ confronts and transforms the power of the state and capital” (Healey, 1996, p. 3).

In 2011 UNESCO adopted the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL). The approach embodied in the HUL that provides a ‘tool’ for not only managing change in the city and integrating conservation as an integral driver for urban planning, but also for giving people a voice in deciding which values are important enough to transmit to future generations and engendering partnerships to this aim (UNESCO 2011). This is very important for us, and the point of this essay: only through participatory communicative planning and design can we include the values of all members of a community in the design process and can decide, together, what is heritage and how it should be managed. As we have tried to demonstrate, this is not only the “right thing” to do, but it is also more effective and has the potential to deliver better results.

Rather than diminishing the roles of professional designers, planners and heritage experts, this perspective gives those experts new and innovative roles. They become steerers of public discussion and their role changes from “top-down designers of heritage” to “co-designers of heritage”. They are still specialists, but rather than taking decisions on their own, they can help decision-makers take the right decisions in partnership with citizens.

Values in practice

How does this translate into practice? The bottom-up participatory approach does not invalidate the top-down expert opinion. Rather, the two approaches should be seen as complimentary to each other. To be able to participate in value-driven discussions, built environment practitioners need to be able to understand the language of values (terminology) and how values relate to each other in the built environment. For the Dutch context, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands have defined a value set to assess built heritage consisting of:

- Cultural-historical values,

- Architectural and art-historical values,

- Setting and ensemble values,

- Integrity and distinctiveness,

- Rarity value. (RCE, 2019)

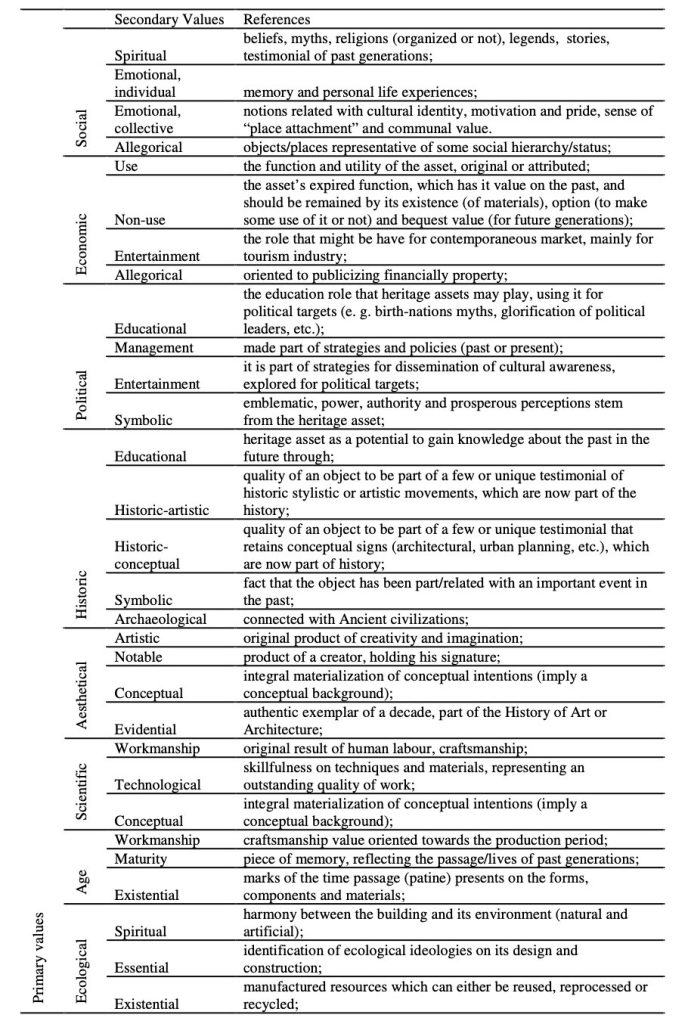

This value-set can often be recognised in the statements of significance of buildings protected at a national, provincial or municipal level. Internationally, many other value sets are used, and built heritage values are only a part of a larger set of what are known as cultural values, of which an overview has been created by Tarrafa Silva & Pereira Roders (2012) [Table 16.1.1], as a refinement of the research presented by Pereira Roders in her PhD thesis (Pereira Roders, 2007). It is important to emphasise that these values don’t exist in themselves. They emerge only because of the existence of tangible and intangible attributes, such as materials, form, design, use, location, spirit, etc.

Experts such as architectural historians have been trained to investigate historic buildings, areas or landscapes through archival research, on-site investigations, comparison to other similar and different buildings, areas or landscapes, to come to an abstraction of their heritage values. More recently,

designers are often faced with the challenge of translating these abstractions contained in statements of significance back to the built fabric they describe. This can be seen as a process of reverse-engineering: walking back the process of valuation. This can be quite a daunting task, but there are tools to assist students and professionals to navigate this process.

One such tool is the building-scale based Interpretation and Valuation process described by Kuipers & De Jonge (2017). This step-by-step guide can be used to not only understand which qualities of a monument are legally protected, but also help in discovering other built heritage values and attributes, through a process of Chronomapping (mapping the stages and of development of a building), analysing the values and attributes through use of the Heritage Value Matrix, and then searching for the challenges or dilemmas presented by the proposed change (Clarke, et al. 2019), to come to a conclusion about the limits of acceptable change. Other more complex processes, such as Heritage Impact Assessments (HIAs), measure the impact of a project proposal on heritage values. HIA processes identify values and attributes, define impacts and measure them against the values established beforehand. If changes to attributes that support values are inevitable, the HIA can propose ways in which to reduce or compensate these impacts (called mitigation).

The instruments described above may sound very technical and top-down, but when carried out well, they can be important tools for public engagement. Valuation and HIAs should always include stakeholder engagement (ICOMOS 2011). But often these processes do not yet go far enough to actively engage stakeholders in participatory planning and co-design. Also, values evolve over time through the continuous changes in perceptions of society (Council of Europe, 2005, Article 2). What was described as being of value when a building or landscape was legally protected is never a complete representation of the built or landscape heritage value it contains at a specific time. And unprotected buildings or landscapes can also contain values. The Council of Europe Faro Convention (2005) recognizes “…the need to put people and human values at the centre of an enlarged and cross-disciplinary concept of cultural heritage” and aims to emphasize (…) the value and potential of cultural heritage wisely used as a resource for sustainable development and quality of life in a constantly evolving society”.

New methods of sourcing values though participatory processes are currently being developed. Analogue methods, such as stakeholder interviews, polls, discussions and debates can be augmented through digital research using social media and sensing technologies. Gamification now offers new processes to enhance values-based participatory planning and co-design.

Conclusions

Communicative rationality as a theory has had a profound impact on how we conceive urban planning and design, through communicative and participatory planning and co-design. We believe this approach is valuable for the planning and design of our cities and of our heritage as well. For Healey, these ideas have the potential to reconstruct democratic practice towards more inclusive participatory forms of democracy based on inclusionary argumentation. Inclusionary argumentation (Healey, 1997) implies public reason that “accepts the contributions of all members of a political community and recognises the range of ways we have of knowing”. As a practice, Healey argues, it has the potential to regenerate the public realm in which diverse issues and diverse ways of raising issues can be given attention. In such situations, Healey argues, the power of the ‘better argument’ confronts and transforms the power of the state and capital (Healey, 1996). The process of surveying, defining and communicating values connected to the heritage of a city or region have therefore the potential to deliver the right to the city and to create a more inclusive city for all, in which all kinds of values are recognised and represented in the public sphere.

Values only exist when they are commonly held. Built heritage values emerge through communication between people exchanging ideas about the existing environment the humans have created. Where in the past this communication was between experts, we are now broadening the discussion to include every stakeholder. Values are our intangible commons, and their curation should be a common endeavour.

References

Aalbers, M. B., & Gibb, K. (2014). Housing and the Right to the City: introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Housing Policy, 14(3), 207-213.

Carlisle, K., & Gruby, R. L. (2019). Polycentric Systems of Governance: A Theoretical Model for the Commons. Policy Studies, 47(4), 921-944.

Clarke, N., Zijlstra, H., & de Jonge, W. (2019). Education for adaptive reuse: The TU Delft Heritage and Architecture experience. DOCOMOMO Journal, 61(3), 67–75.

COUNCIL OF EUROPE. (2005). Council of Europe framework convention on the value of cultural heritage for society: Faro, 27.X.2005 = Convention-cadre du Conseil de ‘Europe sur la valeur du patrimoine culturel pour la societe ; Faro, 27.X.2005. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

European Commission. (2020). “The principle of subsidiarity.” from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/7/the-principle-of-subsidiarity [Online Resource].

Fischer, F. (1990). Technocracy and the Politics of Expertise. London: Sage.

Harvey, D. (2008). The Right to the City. New Left Review, Sept/ Oct(53), 23-40. Retrieved from https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii53/articles/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city

Healey, P. (1996). The communicative turn in planning theory and its implications for spatial strategy formation. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 23, 217-234.

Held, D. (1987). Models of Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Holden, G. (2018). Top-up: Urban Resilience through Additions to the Tops of City Buildings. In H. Remøy, & S. J. Wilkinson, (Eds.), Building Urban Resilience Through Change of Use (pp. 105-120). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

ICOMOS (2011). Guidance on Heritage Impact Assessment for Cultural World Heritage Properties. Paris: International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS)

Imperial, M. T. (1999). Institutional Analysis and Ecosystem‐Based Management: The Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Environmental Management, 24(4), 449-465.

Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, 2015. Erfgoedwet. s.l: sn.

Kuipers, M., & De Jonge, W. (2017). Designing from Heritage: Strategies for Conservation and Conversion. Delft: BK Books. Available from: https://books.bk.tudelft.nl/press/catalog/book/isbn.9789461868022.

Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la ville. Paris: Anthropos.

Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

McGinnis, M. D., & Ostrom, E. (2011). Reflections on Vincent Ostrom, Public Administration, and Polycentricity. Public Administration Review, 72(1), 15-25.

Mitchell, D., & Villanueva, J. (2010). Right to the City. In R. Hutchinson, M. B. Aalbers, R. A. Beauregard, & M. Crang (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of Urban Studies (pp. 667-671). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, V., Tiebout, C. M., & Warren, R. (1961). The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry. American Political Science Review, 55, 831-842.

Pereira Roders, A.R. (2007). Re-architecture : lifespan rehabilitation of built heritage. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

RCE [Rijksdienst voor Cultureel Erfgoed], 2019. “Waarderingescriteria”. from https://www.cultureelerfgoed.nl/onderwerpen/waarderen-van-cultureel-erfgoed/documenten/publicaties/2019/01/01/waarderingscriteria [Online Resource].

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2018). “Urbanization.” from: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization [Online Resource].

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Tarrafa Silva, A. & Pereira Roders, A. (2012). Cultural Heritage Management and Heritage (Impact) Assessments. Cape Town: Joint CIB

W070, W092 & TG72 International Conference on Facilities Management, Procurement Systems and Public Private Partnership.

UNESCO (2011). Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Paris: UNESCO

UNESCO (2012). “Rio de Janeiro: Carioca Landscapes between the Mountain and the Sea.” from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1100/ [Online Resource].