14 Achilles Tendon Rupture

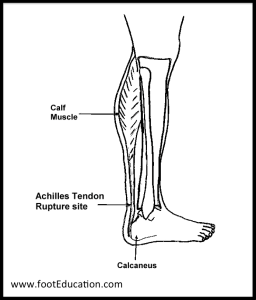

The most common acute injury to the Achilles tendon is a complete rupture. This injury typically occurs in men in their 30s and 40s. The inciting event often is an athletic activity that requires a sudden acceleration or changes in direction (ex. basketball, tennis, soccer). Ruptures typically occur 2 to 5 cm proximal to insertion into the calcaneus.

Structure and function

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the body. The two main calf muscles, the soleus and gastrocnemius, coalesce to form the Achilles tendon, which then inserts into the posterior aspect of the calcaneus (Figure 1).

The Achilles functions to control the body as the center of gravity rotates over the foot. Without a functional Achilles, patients limp and have a markedly dysfunctional gait.

Patient Presentation

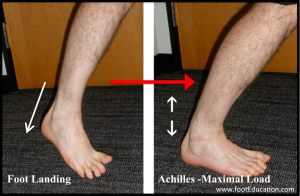

Achilles tendon ruptures usually occur when an athlete loads the Achilles immediately prior to pushing off. This can occur when suddenly changing directions, starting to run, or preparing to jump (Figure 2). A sudden change in direction requires the calf muscle to contract while still lengthening (eccentric loading). This subjects the Achilles tendon to a large loading force, which may cause the tendon to fail. To be clear, the tendon tears because of the large internal forces generated by the eccentric contraction of the calf muscle and applied to the Achilles – and not because of an external force. In such a sense, it may be said that the patient tore the tendon himself. This explains why many patients feel as if they were “hit on the back of the leg” even though no one was around them when the injury occurred.

Objective Evidence

Achilles tendon tears are more common in middle-aged men who exercise intensely but intermittently (the so-called “weekend warrior”). With age the Achilles tends to lose flexibility and may develop areas of tendonosis (degenerative changes) that can serve to weaken the tendon.

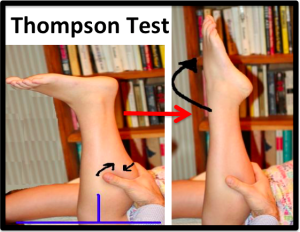

A diagnosis of an Achilles rupture must be considered in any patient who reports an acute mechanism of injury (or acute change in symptoms) implicating the heel or soft tissues above it. In those patients, the examiner can exclude an Achilles tendon rupture) with the Thompson test. (Figure 3).

The Thompson test, as shown, takes advantage of the fact that squeezing the patient’s calf muscles with the knee flexed should induce plantar flexion of the ankle if and only if the Achilles is intact. The patient lays prone on the examining table. The affected leg is flexed 90, perpendicular to the table (blue lines). The examiner firmly squeezes the gastrocnemius (black arrows). The examiner examines the ankle for plantar flexion.

Two points are worth noting:

- The nomenclature of the Thompson test can be confusing: a “positive” Thompson test is the absence of motion (whereas “positive” using means something was affirmatively observed). It is therefore helpful to describe the results as “positive for rupture” or “negative for rupture.”

- The Thompson test is necessary because testing active ankle plantar flexion can be misleading: an intact posterior tibialis and the flexors of the toe, which are both (weak) ankle flexors as well, might mask a torn Achilles. With these tendons intact, a patient with a ruptured Achilles may still be able to actively flex the ankle, especially without resistance.

A patient presenting with Achilles tendon rupture will often describe a sharp intense pain in the back of their heel at the time of the injury. Patients often initially report that they were “struck in the back of the heel” only to realize that this was not the case, as there was no one around them. After the injury, patients may have some swelling. If they can walk at all, it will be with a marked limp.

Note that Achilles tendonitis or a partial rupture of the calf muscle (gastrocnemius) as it inserts into the Achilles can also cause symptoms that suggest a tendon rupture. The Thompson test is helpful (indeed essential) here.

At times, an Achilles tendon rupture is obvious on physical examination: a substantial defect in the Achilles 2-5 cm proximal to where it normally inserts into the heel bone is appreciated, beyond the positive Thompson test.

Imaging Studies

Plain x-rays will be negative in patients who have suffered an Achilles tendon rupture unless the Achilles injury involved an avulsion (traumatic displacement of a bony fragment from the calcaneus). Avulsions are rare, except in older patients with weaker bone.

Achilles rupture can be seen on ultrasound or MRI. However, these studies are usually not needed as a good history and well-performed physical exam should cinch the diagnosis. However, an MRI may be justified when the history or physical exam is ambiguous, or the quality of the tendon is in question (and whether it is amenable to repair) in the setting of chronic tendinopathy.

Epidemiology

Achilles tendon rupture is a common injury that occurs at an incidence of 2.66 per 1000 persons years or 18 per 100,000 population (PMID: 23386750). Middle-aged males are the largest group affected by this injury, and most injuries occur during athletic participation, most commonly basketball, soccer, or tennis.

Red flags

Acute pain in the vicinity of the Achilles tendon or weakness of plantar flexion should be considered a “red flag” for an Achilles tendon rupture, prompting the examiner to perform the Thompson test.

Treatment options and Outcomes

Achilles tendon ruptures can be treated with either surgical repair or relative immobilization. If the ruptured tendon is ignored (or not correctly diagnosed) the tendon ends will retract, leading to failure of the calf muscle and a dysfunctional lower leg.

The medical literature suggests that ruptures treated with surgery are less likely to re-rupture, though there are complications (such as wound breakdown) that are unique to surgery. A published expected-value decision analysis on this issue reported that the optimal management strategy is highly dependent on patient preferences.

Non-Operative Treatment of Achilles Tendon Ruptures

Non-operative treatment consists of placing the foot in a downward position [equinus] initially, a position that encourages the torn ends to contact each other. Once there is some healing, the foot can be advanced to a more neutral position. Early weight-bearing and controlled active plantar flexion has been shown to improve non-operative treatment. However, care must be taken to avoid excessive dorsiflexion (extension), a position that encourages the torn ends to separate from each other.

It is important to monitor the status of the Achilles throughout non-operative treatment. This can be done by examination or via ultrasound. If there is evidence of gapping or non-healing, surgery may need to be considered.

The primary advantage of non-operative treatment is avoiding an incision in an area with a vascularity that puts the incision at higher risk for wound healing problems and infection. The main disadvantage of non-operative treatment is that the recovery appears to be somewhat slower and the re-rupture rate appears to be higher.

Operative Treatment of Achilles Tendon Ruptures

Operative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures involves opening the skin and identifying the torn tendon. This is then sutured together to create a stable construct. By suturing the torn tendon ends together and assuring continuity even if the ankle is not in full plantar flexion, the patient can be mobilized more quickly.

Risk factors and prevention

Factors that are associated with a higher risk for Achilles rupture include age between 30-50, male sex, playing recreational sports (most typically soccer, basketball, and tennis), prior steroid injections, and taking fluoroquinolone antibiotics.

Key terms

Achilles tendon rupture; Thompson test

Skills

Bedside skills for the diagnosis of disorders of the Achilles include the ability to take a detailed but focused history and perform a thorough musculoskeletal examination. Specifically, students should be able to perform and interpret the Thompson test.