1 Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle

A solid understanding of anatomy is essential to effectively diagnose and treat patients with foot and ankle problems. Anatomy is a road map. Most structures in the foot are fairly superficial and can be easily palpated. Anatomical structures (tendons, bones, joints, etc) tend to hurt exactly where they are injured or inflamed. Therefore a basic understanding of surface anatomy allows the clinician to quickly establish the diagnosis or at least narrow the differential diagnosis. For those conditions that require surgery a detailed understanding of anatomy is critical to ensure that the procedure is performed efficiently and without injuring any important structures. With a good grasp of foot anatomy it readily becomes apparent which surgical approaches can be used to access various areas of the foot and ankle.

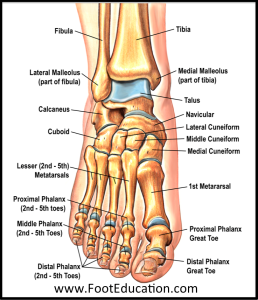

There are a variety of anatomical structures that make up the anatomy of the foot and ankle (Figure 1) including bones, joints, ligaments, muscles, tendons, and nerves. These will be reviewed in the sections of this chapter.

Regions of the Foot

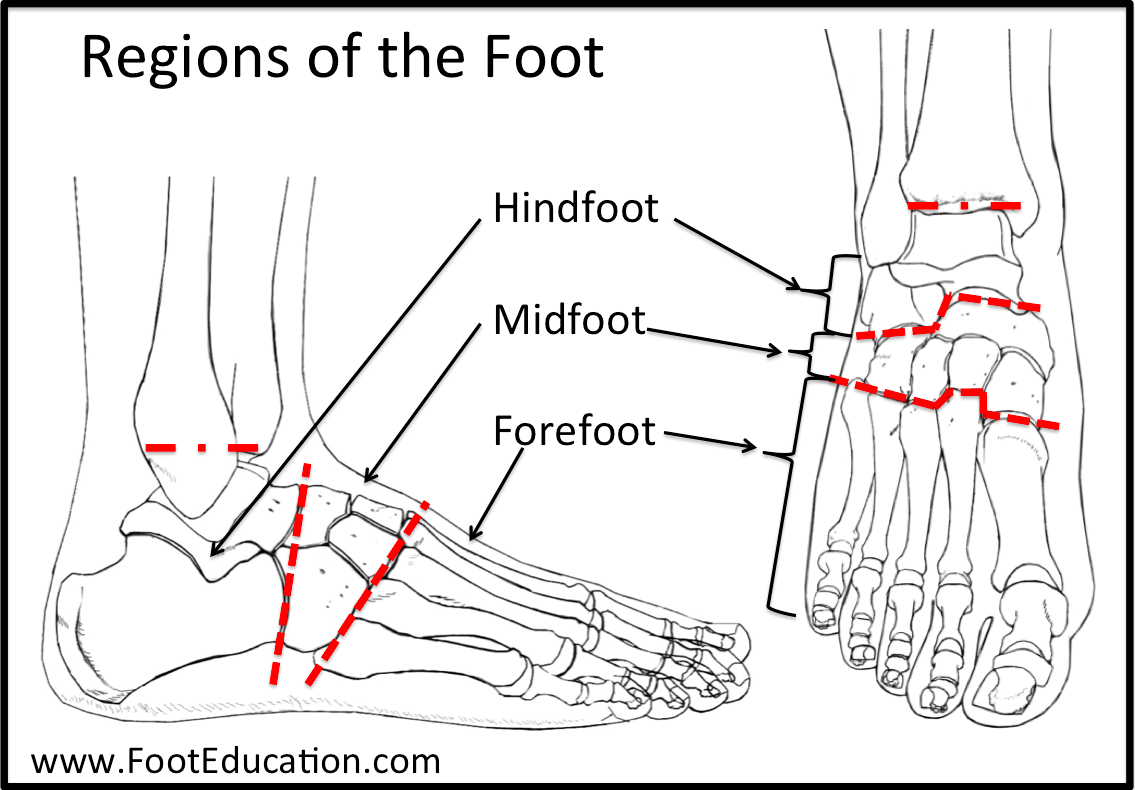

The foot is traditionally divided into three regions: the hindfoot, the midfoot, and the forefoot (Figure 2). Additionally, the lower leg often refers to the area between the knee and the ankle and this area is critical to the functioning of the foot.

The Hindfoot begins at the ankle joint and stops at the transverse tarsal joint (a combination of the talonavicular and calcaneal-cuboid joints). The bones of the hindfoot are the talus and the calcaneus.

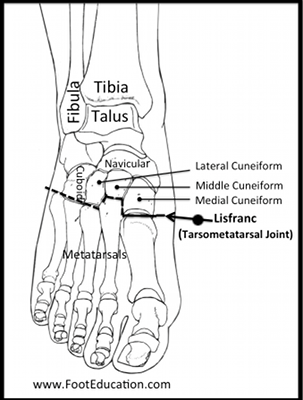

The Midfoot begins at the transverse tarsal joint and ends where the metatarsals begin –at the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. While the midfoot has several more joints than the hindfoot, these joints have limited mobility. The five bones of the midfoot comprise the navicular, cuboid, and the three cuneiforms (medial, middle, and lateral).

The Forefoot is composed of the metatarsals, phalanges, and sesamoids. The bones that make up the forefoot are those that are last to leave the ground during walking. There are twenty-one bones in the forefoot: five metatarsals, fourteen phalanges, and two sesamoids. The great toe has only a proximal and distal phalanx, but the four lesser toes each have proximal, middle, and distal phalanges, which are much small than those of the great toe. There are two sesamoid bones embedded in the flexor hallucis brevis tendons that sit under the first metatarsal at the level of the great toe joint (1st metatarsophalangeal joint).

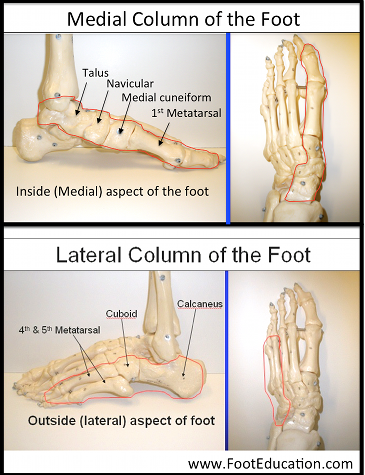

Columns of the Foot

The foot is sometimes described as having two columns (Figure 3). The medial column is more mobile and consists of the talus, navicular, medial cuneiform, 1st metatarsal, and great toe. The lateral column is stiffer and includes the calcaneus, cuboid, and the 4th and 5th metatarsals.

Bones and Joints

The foot is comprised of 28 bones (Figure 1). Where two bones meet a joint is formed –often supported by strong ligaments. It is helpful to think of the joints of the foot based on their mobility (Table 1). A few of the joints are quite mobile and are required for the foot to function normally from a biomechanical point of view. These are often referred to as essential joints. There are some joints that move a moderate amount, and there are other joints that are held tightly together with strong ligaments. These non-mobile joints are sometimes referred to as non-essential joints. (This may be a poor term in that it incorrectly implies that the joints are not important; they are important. Rather the correct sense is only that movement from these joints is less critical.)

| Mobile Joints of the Foot and Ankle (Essential Joints):

Ankle joint (tibiotalar joint) Subtalar joint Talonavicular joint (TN joint) Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints |

| Joints that Move a Moderate Amount:

Calcaneal-cuboid joint Cuboid-metatarsal joint for the fourth and fifth metatarsal. Proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) Distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) |

| Joints with Minimal Movement (Non-Essential Joints):

Navicular-cuneiform joints Intercuneiform joints Tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint “Lisfranc” Joint (a.k.a. midfoot joint) |

Bones of the lower leg and hindfoot: Tibia, Fibula, Talus, Calcaneus.

Joints of the hindfoot: Ankle (Tibiotalar), Subtalar.

Tibia and Fibula (long bones)

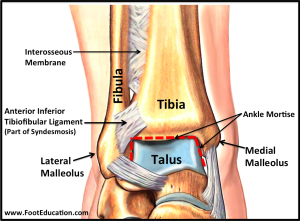

The foot is connected to the body where the talus articulates with the tibia and fibula. In a typical foot the tibia is responsible for supporting about 85% of body weight. The fibula accepts the remaining 15%; its main role is to serve as the lateral wall of the ankle mortise (Figure 4). The tibia and fibula are held together by the tibiofibular syndesmosis, a collection of 5 ligaments. The prominence on the medial side of the distal tibia is known as the medial malleolus; the distal aspect of the fibula is known as the lateral malleolus.

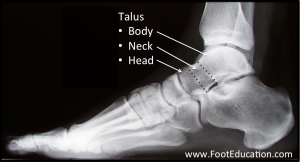

Talus

The talus is the top (most proximal) bone of the foot. Because it articulates with so many other bones, 70% of the talus is covered with hyaline cartilage (joint cartilage). The talus connects to the calcaneus on the underside through the subtalar joint, and distally it connects to the navicular through the talonavicular joint. These articulations allow the foot to rotate smoothly around the talus. Owing primarily to the fact that no tendons attach to it and that most of its surface is cartilage, the talus has a relatively poor blood supply. The lack of a robust blood supply means that injuries to this bone take greater time to heal than might be the case with other bones—and some injuries will not heal at all.

The talus is generally thought of as having three parts: the body, the head, and the neck (Figure 5). The talar body, which is roughly square in shape and is topped by the dome, connects the talus to the lower leg at the ankle joint. The talar head is adjacent to the navicular bone to form the talonavicular joint. The talar neck is located between the body and head of the talus. The talar neck is one of the few areas of the talus not covered with cartilage, and is thus the point of entry for the blood vessels supplying the talus.

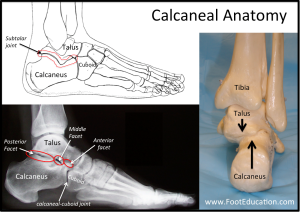

Calcaneus

The calcaneus is commonly known as the heel bone. The calcaneus is the largest bone in the foot, and along with the talus, it makes up the area of the foot known as the hind-foot. There are three protrusions (anterior, middle, and posterior facet) on the superior surface of the calcaneus that allow the talus to sit on top of the calcaneus, forming the subtalar joint (Figure 6). The calcaneus also connects to the cuboid bone to form the calcaneal-cuboid joint.

Subtalar Joint

The talus rests above the calcaneus to form the subtalar joint (Figure 6) slightly offset laterally, towards the 5th metatarsal/small toe. This lateral positioning allows greater flexibility in inversion/eversion (tilting). The subtalar joint moves in concert with the talonavicular joint and the calcaneocuboid joint, two joints located near the front of the talus.

Bones of the midfoot: Cuboid, Navicular, Cuneiform (3).

Joints of the midfoot: talonavicular, calcaneocuboid, intercunneiform, tarsometatarsal (TMT).

Cuboid

The cuboid bone is a square-shaped bone on the lateral aspect of the foot. The main joint formed with the cuboid is the calcaneocuboid joint, where the distal aspect of the calcaneus articulates with the cuboid.

Navicular

The navicular is distal to the talus and connects with it through the talonavicular joint. The distal aspect connects to each of the three cuneiform bones. Like the talus, the navicular has a poor blood supply. On its medial side (closest to the middle of the foot) the navicular tuberosity is the main attachment of the posterior tibial tendon.

Transverse Tarsal Joint

The transverse tarsal joint is not a true joint, but the combination of the calcaneocuboid and talonavicular joints. When these two joints are aligned in parallel, the foot is flexible yet when their axes are divergent, the foot becomes stiff. The shift from a flexible state to a stiff one allows the foot to serve as a shock absorber and as a rigid level in different phases of gait.

Cuneiforms

There are three cuneiform bones in the foot: the medial, medial (intermediate), and lateral cuneiforms (Figure 7). These bones, along with the strong plantar and dorsal ligaments that connect to them, provide a good deal of stability for the foot.

Bones of the forefoot: Metatarsals (5), Phalanges (14), Sesamoid Bones (2)

Metatarsals

Each foot contains five metatarsals, numbered 1-5 medial (great toe) to lateral. The first three metatarsals medially are more rigidly held in place than the lateral two. The metatarsals articulate with the mid-foot at their base, a joint called the tarsal-metatarsal (TMT) joint, or Lisfranc joint. The TMT joint is made stable not only by strong ligaments connecting these bones, but also because the second metatarsal is recessed into the middle cuneiform in comparison to the others (Figure 7). The metatarsal heads are the main weight bearing surface and the site where the phalanges attached at the metatarsal-phalangeal (MTP) joint.

Phalanges

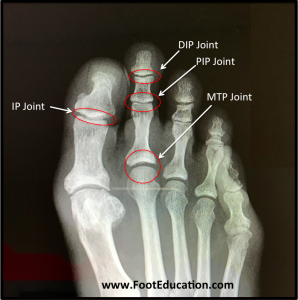

The first toe, also known as the great toe or hallux, is the only one to have two phalanges; the other lesser toes have three. These are known as the proximal phalanx (closest to the ankle) and the distal phalanx (farthest from the ankle). The phalanges form interphalangeal joints between themselves: a proximal interphalaneal joint (PIP) and the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) (Figure 8).

Sesamoid Bones

In the foot, there are two sesamoid bones located directly underneath the first metatarsal head, embedded in the medial (tibial) side and lateral (fibular) aspect of the flexor hallucis brevis tendon.

Common Ossicles of the Foot

Some feet contain accessory ossicles or accessory bones (Figure 9). These extra bones are developmental variants. Over 40 different ossicles of the foot have been reported. The most common accessory bones include:

Os Trigonum: Found at the posterior aspect of the talar body, this ossicle is connected to the talus via a fibrous union that failed to unite (ossify) between the lateral tubercle of the posterior process. An os trigonum is present in about 10% of the population.

Os Naviculare (Os Tibiale Externum or Accessory Navicular): This bone represents a failure to unite the ossification center the navicular tuberosity (where the tibialis posterior tendon inserts) to the main center of the bone. It is present in about 15% of the population.

Os Peroneum: This extra bone is found within the peroneus longus tendon sheath at the point where it wraps around the cuboid. It has been reported in about 20% of patients.

Bipartite Sesamoid: This condition occurs when one of the sesamoids associates with the great toe fails to ossify resulting in two bone segments connected by a fibrous union. It can be mistaken for a sesamoid fracture. Bipartite sesamoids are seen in about 20% of the population with more than 90% of them occurring in the tibial sesamoid.

Os Subfibulare: This extra bone is seen at the type of the fibula. It can be mistaken for an avulsion fracture. It is seen in 1-2% of the population.

Ligaments

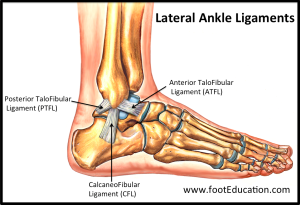

The Anterior TaloFibular Ligament (ATFL)

The anterior talofibular ligament (Figure 10) is the most commonly injured ligament when an ankle is sprained. The ATFL runs from the anterior aspect of the distal fibula (lateral malleolus) down and to the outer front portion of the ankle in order to connect to the neck of the talus. It stabilizes the ankle against inversion, especially when the ankle is plantar-flexed.

The CalcaneoFibular Ligament (CFL)

The calcaneofibular ligament (Figure 10) is also on the lateral side of the ankle. It starts at the tip of the fibula and runs along the lateral aspect of the ankle and into the calcaneus. It too resists inversion, but more when the ankle is dorsiflexed.

Posterior TaloFibular Ligament

The posterior talofibular ligament runs from the back lower part of the fibula and into the outer back portion of the calcaneus (Figure 10). This ligament functions to stabilize the ankle joint and subtalar joint.

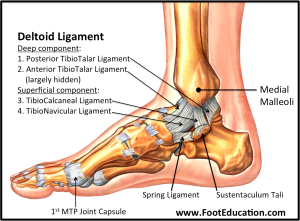

The Deltoid Ligament

The deltoid ligament is a fan shaped band of connective tissue on the medial side of the ankle (Figure 11). It runs from the medial malleolus down into the talus and calcaneus. The deeper branch of the ligament is securely fastened in the talus, while the more superficial, broader aspect runs into the calcaneus. This ligament functions to resist eversion.

Spring Ligament

The spring ligament (Figure 11) is a strong ligament that originates on the sustentaculum tali – a bony prominence of the calcaneus on the medial aspect of the hindfoot. The spring ligament inserts into the plantar medial aspect of the navicular and serves to cradle and support the talar head.

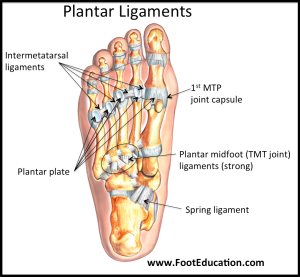

Lisfranc Ligaments

The Lisfranc joint complex is a series of ligaments that stabilize the tarsometatarsal joints. These ligaments prevent the joints of the midfoot from moving much, and as such provide considerable stability to the arch of the foot. The plantar ligaments are stronger than those on the dorsal side (Figure 12 & 13). The Lisfranc ligament is a strong band of tissue that connects the medial cuneiform to the base of the second metatarsal.

The Inter-Metatarsal Ligaments

These ligaments run between the metatarsal bones at the base of the toes (Figure 12). They connect the neck region of each metatarsal to the one next to it, and bind them together. This keeps the metatarsals moving in sync. While it is possible to tear these ligaments, it is also possible for them to irritate the digital nerve as it crosses the ligaments creating a Morton’s neuroma.

The 1st MTP joint Capsule of the Great Toe

The connective tissue of this ligament takes the form of a capsule (Figure 12). It goes from the medial portion of the first metatarsal head and stretches to the distal phalanx on the same side. This allows this ligament to stabilize the great toe on the medial side. In the situation where a person develops a bunion, this band gets stretched out, and the great toe changes position and becomes angulated outward.

Anterior Inferior TibioFibular Ligament (AITFL)

The anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (Figure 4) is positioned on the anterolateral aspect of the ankle joint and serves to helps keep the tibia and fibula together. Injuries to this ligament, so called high ankle sprains, occur when the foot is stuck on the ground while the leg rotates inwards.

The Interosseous Membrane

The interosseous membrane is composed of strong fibrous tissue and runs along the tibia and fibula, and keeps the two bones moving as one unit (Figure 4).

The syndesmosis

The ligament group formed by the AITFL and the interosseous membrane, joined by the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, the transverse ligament and the interosseous ligament is known as the syndesmosis. The function of the syndesmosis is to hold the tibia and fibula together at the appropriate distance, thereby forming the mortise into which the talus sits

Muscles and Tendons

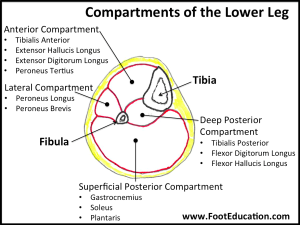

There are four muscle compartments in the lower leg (Figure 13) each separated by strong fascia:

- the superficial posterior compartment;

- the deep posterior compartment;

- the anterior compartment and;

- the lateral compartment

Collectively the muscles in these four compartments are referred to as the extrinsic muscles of the foot because they originate above the foot in the leg, but insert within the foot.

Superficial Posterior Compartment

The superficial posterior compartment of the leg holds the two large muscles of the calf, the gastrocnemius and the soleus, which both run along the length of the leg joining to form the Achilles tendon. Both gastrocnemius and soleus muscles are innervated by the tibial nerve. The gastrocnemius is the more superficial of the posterior calf muscles. It originates above the knee joint, off the posterior femur, and inserts into the calcaneus. The soleus is the deeper of the two muscles of the calf and does not cross the knee. There is a smaller third muscle of the superficial posterior compartment called the plantaris. It is very small and not functionally important in most people (but is subject to injury nonetheless).

Deep Posterior Compartment

This muscle compartment is located on the backside of the leg deep to the soleus muscle. There are three muscles in this compartment, the flexor hallucis longus, the flexor digitorum longus, and the tibialis posterior. All three of these muscles cross the ankle and insert on bones of the foot, the hallux, the lessor toes and the navicular, respectively. They are innervated by the tibial nerve.

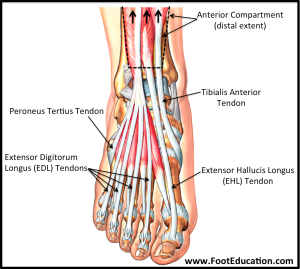

Anterior Compartment

The anterior compartment is comprised of four muscles that extend (dorsiflex) the foot and ankle (Figure 14). The Tibialis Anterior, the Extensor Hallucis Longus, the Extensor Digitorum Longus and the Peroneus Tertius. The deep peroneal nerve innervates all the muscles of the anterior compartment.

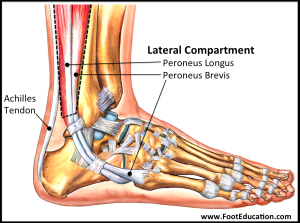

Lateral Compartment

The last of the muscle compartments of the lower leg is the lateral compartment (Figure 15) is comprised of two muscles, the peroneus longus and the peroneus brevis. Both cross the ankle, but the peroneus longus wraps underneath the cuboid crossing the plantar aspect of the foot as well, and inserts at the base of the first metatarsal. The peroneus brevis inserts at the base of the fifth metatarsal on the lateral aspect of the foot. These two muscles work together to evert the foot – move it towards the lateral side. The peroneus longus also functions to plantarflex the first metatarsal. Both of these muscles are controlled by the superficial peroneal nerve.

Muscles within the Foot

There are a large number of smaller muscles deep inside the foot. They help move the toes and stabilize the foot. Collectively they are referred to as the intrinsic muscles of the foot because they are entirely contained within the foot. Only two of these muscles are located on the dorsal aspect (top) of the foot: the extensor hallucis brevis, and the extensor digitorum brevis. They are both innervated by the deep peroneal nerve. Their primary purpose is to help extend the toes. This is in contrast to the flexor hallucis brevis and flexor digitorum brevis. These muscle tendon units are located deep in the plantar arch and respectively assist in flexing the great toe and the four lesser toes. They are innervated by the medial plantar nerve.

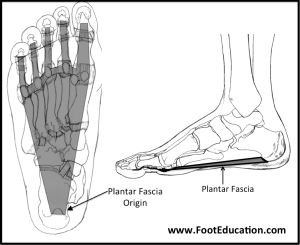

Plantar Fascia

The plantar fascia is not a nerve, tendon or muscle, but rather a strong fibrous tissue (Figure 16). This tissue originates deep within the plantar surface of the calcaneus (heel bone) and covers the distance to the base of each of the five toes. When the foot rolls off the ground during walking, the toes dorsiflex and pull on the plantar fascia. This motion tends to tighten the plantar fascia, and thereby supports the arch of the foot, by maintaining the distance between the calcaneus and the metatarsal heads – a phenomenon known as the windlass mechanism. This stiff and relatively impermeable covering helps to protect the muscles of the sole of the foot.

Nerves

Nerves of the Foot

There are five main nerves that run past the ankle into the foot (Figure 17). All five of these are derived from two nerves that originate from the lumbar spine. The sciatic nerve branches into four of the five primary nerves of the foot. Two segments of the sciatic nerve branch before the knee joint: the tibial nerve and peroneal nerve. The tibial nerve gives off a branch called the sural nerve. Near the level of the knee the peroneal nerve splits into the deep peroneal nerve and the superficial peroneal nerve. The fifth nerve of the foot originates from the femoral nerve and is called the saphenous nerve.

The Deep Peroneal Nerve

The deep peroneal nerve is one of two parts of the peroneal nerve (Figure 17). The deep peroneal nerve runs directly under the head of the fibula. It is responsible for controlling the muscles of the anterior compartment of the leg, and continues down the front of the ankle to the dorsal surface of the foot. It is responsible for the sensation in the small area between the first and second toes, an area known as the first web space. If this nerve doesn’t function, there will be no sensation in this area. If motor function is lost, it becomes impossible to lift the foot upwards, a symptom known as a “drop foot”.

The Superficial Peroneal Nerve

The superficial peroneal nerve is the partner of the deep peroneal nerve (Figure 17). It runs on the lateral side of the leg below the knee under the head of the fibula and innervates the lateral compartment muscles. It runs down over the anterolateral aspect of the ankle and splits into several branches on the dorsal aspect of the foot. The superficial peroneal nerve has both motor and sensory neurons for most of its length, but below the ankle is made entirely of sensory nerves. If motor function of this nerve is lost, it becomes impossible to evert the foot but there is no motor function lost distal to the ankle.

Tibial Nerve

The tibial nerve controls all the muscles behind the tibia and fibula in the back part of the calf (deep and superficial posterior compartment muscles). The tibial nerve continues down into the deep inner part of the ankle and splits into two branches, the medial plantar nerve and the lateral plantar nerve (Figure 17). These two branches provide sensation to the entire sole of the foot, and innervate all the tiny muscles of the sole of the foot.

Sural Nerve

The fourth nerve of the foot is another branch of the tibial nerve, known as the sural nerve (Figure 17). This nerve runs from slightly below the knee to the lateral aspect of the foot. It becomes a very superficial nerve at the level of the posterolateral ankle and continues distally to provide sensation to the outside of the foot. It has no motor function.

Saphenous Nerve

The fifth and last nerve is the only one to branch off from the femoral nerve (Figure 17). It runs from medial aspect of the knee and runs over the anteromedial aspect of the ankle joint to provide sensation to the inside of the foot.

Although the positions of these nerves are generally as described, there is a certain amount of variability in nerve position. They can be located lower or higher than described. These variations must be considered while performing surgery.