9 Arthrosis of the Ankle and Hindfoot

Ankle arthrosis most commonly occurs after a major traumatic ankle injury. A pilon fracture may cause arthrosis of the tibiotalar (ankle) joint; a depressed calcaneal fracture can cause subtalar arthritis. Arthrosis is also seen after less severe injuries, especially if those injuries cause malalignment. Unlike the knee and hip, the ankle joint is a relatively uncommon site for the development of primary osteoarthritis. Arthrosis of the ankle is also treated with methods that would not be used in the knee or hip, as loss of motion to limit pain is better tolerated in the ankle and hindfoot. Thus, bracing and (in more extreme cases) surgical fusion is a commonly used method of treatment though surgical methods to restore small cartilage defects or to preserve motion through joint replacement are also used.

Structure and function

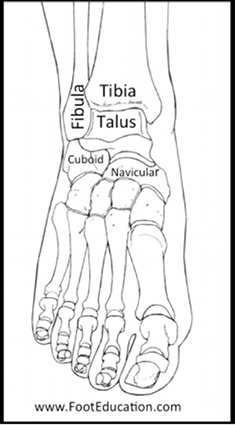

The ankle joint (talocrural or tibiotalar joint) is formed between the distal tibia and fibula and proximal talus (Figure 1). The superior talar dome has three articulating surfaces – medial, central, and lateral – that articulate with the medial malleolus, tibial plafond, and lateral malleolus, respectively. These articulations provide bony stability to the ankle joint when it is in a neutral or dorsiflexed position. In plantarflexion, the ankle joint has considerably less bony contact, and in that position relies more on the surrounding ligaments to provide stability.

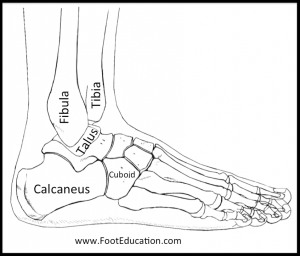

The hindfoot consists of the calcaneus and talus (Figure 2). The inferior aspect of the talus articulates with the calcaneus inferiorly, forming the subtalar joint. The subtalar joint facilitates inversion and eversion of the foot.

The talus is mostly covered by articular cartilage and has no muscular attachments, leaving little bone for vascular penetration. This lack of vascularity predisposes the talus to slow healing and avascular necrosis.

Pathophysiology of osteoarthritis

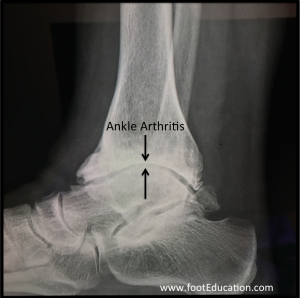

The ankle joint surfaces are highly conforming, that is the surfaces have broad areas of contact. This allows the forces of weight-bearing to be spread out over a maximally large area and in turn minimizes focal joint pressure (Figure 3).

Injuries that damage the articular surfaces can decrease or change contact area, leading to high pressure in certain spots and predisposing the joint to further damage and arthrosis. The hallmark of osteoarthritis is the loss of articular cartilage. Major injury in the ankle will often start the process of osteoarthritis beginning with the breakdown of the joint surface and irritation of the synovium. Thereafter, there is impairment of chondrocyte function and sclerosis of the bone. In the final phase, there is overt disorganization and degeneration. Specifically, when the smooth articular cartilage is damaged, it becomes rough. Friction against the rough surface creates cartilage particles. The synovium absorbs these particles and may undergo a chronic low-grade inflammatory response, producing enzymes that cause further damage. In severe osteoarthritis (Figures 4 & 5), erosion of the articular surface can expose subchondral bone, allowing synovial fluid to enter the cancellous bone causing cysts. The subchondral bone may also thicken due to focal loading forming sclerotic bone. In addition, the inflammation of the joint present in arthritis may contribute to the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs) around the outside of the joint.

Osteoarthritis of the ankle and hindfoot is generally post-traumatic. Primary arthritis of the ankle, in contrast to the knee and hip, is rare.

Osteochondral lesions of the talus can be thought of as a form of focal arthrosis: there is focal cartilage (and possibly bone) damage involving a relatively small portion of the ankle joint (Figure 6), while the remainder of the ankle joint is usually normal. Osteochondral lesions of the talus are also typically caused by trauma to the ankle. Usually it is more minor compressive and rotational forces that shear the cartilage and impact the underlying subchondral bone leading to edema (localized swelling) within the bone. Osteochondral lesions (OCL) of the talus can involve: cartilage only; cartilage and bone; subchondral bone with intact cartilage where there is solely edema of the bone; or where there is bone loss replaced with fluid in the form of a cyst underneath the cartilage. OCLs are typically classified according to whether they are stable/unstable and whether they are displaced or undisplaced.

Virtually all lateral talar OCLs (>90%) are due to trauma compared to roughly 60% of medial lesions. Lesions not caused by trauma may be caused by chronic overload to the foot, repeated microtrauma, avascular necrosis, or congenital factors.

Osteochondral lesions of the talus have poor healing due to the general avascularity of articular cartilage but also the tenuous vascular supply of the talus itself. Though OCLs do not typically heal, they also stay relatively stable over time and very rarely progress to arthritis that encompasses the whole joint.

Patient presentation

Patient presentation will vary depending on the type and location of arthrosis. In general, patients with hindfoot arthritis will present with pain, stiffness, and swelling. Symptoms are often exacerbated by activity and relieved with rest. It is important to determine the exact nature, location, duration, and progression of symptoms to narrow down the type of arthrosis and structures affected.

Localizing the area of maximal discomfort can narrow the differential. In the case of ankle osteoarthritis, pain is often on the anterior aspect of the ankle joint in a bandlike pattern along the tibiotalar joint. In subtalar arthritis, the pain is often localized to the lateral hindfoot, often underneath the fibula in the sinus tarsi, though sometimes the pain radiates medially as well. Patients with talar lesions often complain of localized ankle pain on either the medial or lateral sides of the ankle.

Identifying aggravating and alleviating factors can also help to identify the location of the arthritis. Pain with plantarflexion can indicate a posterior lesion of the talus, while dorsiflexion may aggravate an anterior lesion. If bone spurs are present impingement may occur with resulting pain as the bone spurs come into contact. Some patients may in fact wear high-top boots or shoes after they discover that these shoes alleviate symptoms by preventing excess dorsiflexion. Subtalar arthritis is commonly aggravated by walking on uneven ground because inversion/eversion occurs primarily at the subtalar joint.

Crepitus, catching, locking, grinding or the sensation of a loose body should increase your suspicion for an OLT with an unstable fragment. However, some patients with OLTs are asymptomatic and with the OCL being identified as an incidental finding on an MRI for another problem.

History

Patients with ankle or hindfoot arthrosis frequently describe a history of trauma to the joint (ankle fracture, tibia fracture, recurrent ankle sprains, etc.). This trauma may have been many years in the past. It is important to determine the type of injury – fracture or sprain – and the structures involved. A history of ankle inversion injury that doesn’t improve with conservative treatment should heighten the examiner’s suspicion for a persistent cartilage injury.

In patients in whom a history of trauma is not recalled, asking about personal history or family history of inflammatory arthritis (ex. rheumatoid arthritis) is important, though inflammatory arthritis normally presents elsewhere before affecting the ankle.

Physical exam

When evaluating a patient, check the alignment of the lower extremity – including the alignment of the knees and the hindfoot.

Determine the motion of the ankle and hindfoot joints by assessing ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion – and hindfoot inversion and eversion.

Assess for ankle stability using an anterior drawer test and a talar tilt test.

Other physical exam findings may include a joint effusion, tenderness to palpation over medial and/or lateral joint lines, decreased strength or calf atrophy from relative disuse.

Subtalar arthritis will tend to have hindfoot swelling, tenderness within the tarsal sinus, pain with inversion/eversion, and limited ROM at the subtalar joint. As always, perform a detailed neurovascular exam to look for weakness, loss of sensation, and decreased or absence of distal pulses.

When performing a physical examination, it is always important to look at both feet and ankles so that a normal baseline may be established for a patient.

Objective evidence

Radiographic imaging is used to confirm a clinical diagnosis of arthrosis and often establishes the definitive diagnosis of arthritis. Weight-bearing anterior-posterior, lateral, and mortise/oblique views of the ankle and foot are required. Two additional views can also be used to evaluate the subtalar joint:

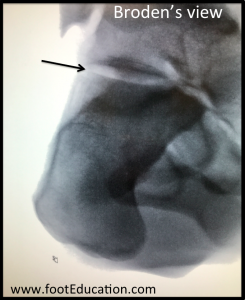

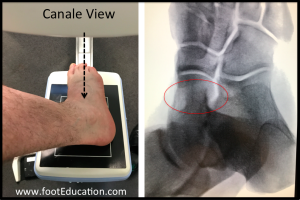

Broden’s view (Figure 7): Foot internally rotated 45 degrees. X-ray angled 10-40 degrees cephalad. Used to evaluate the posterior subtalar facet.

Canale view (Figure 8): Foot pronated 15 degrees. X-ray aimed 75 degrees from horizontal on AP view. Used to evaluate the tarsal sinus.

Plain x-rays may demonstrate one or more of the four cardinal signs of arthritis:

- Narrowing of the joint space,

- Bone spurs (osteophytes),

- Subchondral cysts, and

- Bone whitening (subchondral sclerosis).

Radiographic imaging will not catch a purely cartilage injury or underlying bone edema. In these cases, if arthrosis is suspected but not visualized on x-ray, other imaging modalities (CT or MRI) are necessary to visualize the lesion. These modalities may also help determine if there is another source of pain (e.g., posterior tibial tendonitis, peroneal tendonitis, etc.).

A CT scan will provide a 3 dimensional view of the hindfoot and is generally used when trying to better visualize the 3 dimensional bony structure. CT scans can show subchondral cysts and joint space narrowing which are the hallmarks of arthritis and can help to visualize the subtalar joint that may not be visualized well on plain radiographs. It can also demonstrate the cystic change underneath an OCL.

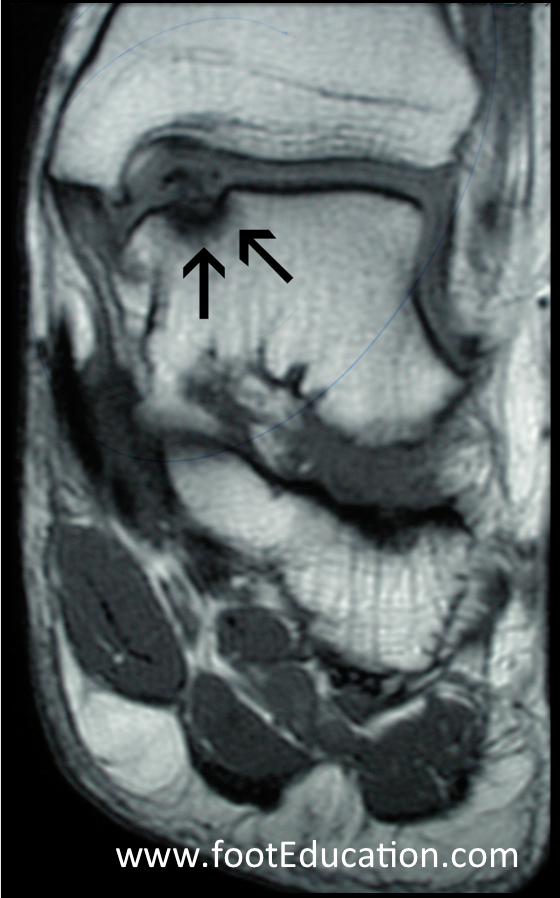

MRI is a powerful tool because it can assess concomitant soft tissue pathology and chondral lesions with great accuracy (Figures 9). However, an MRI should only be ordered when there is a specific clinical question that needs to be answered (ex. “Does this patient have a OLT that is not seen on plain x-rays?”) AND the answer to that question will change your management (ex. “Given this patient’s symptoms if he/she has a large OLT on MRI, I will recommend surgery”).

An MRI is rarely used in the diagnosis or treatment of ankle osteoarthritis, but it is more useful when focal talar lesions are suspected. MRI is the most sensitive tool for diagnosing these lesions because of its ability to detect bone bruising, cartilage damage, or fluid surrounding the lesions

Laboratory tests are generally not useful in diagnosing primary arthrosis but can be used to exclude other conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and gout (See below).

A diagnostic injection of local anesthetic into the ankle or subtalar joint can also help confirm pain as originating from the ankle or subtalar arthritis. For example, if the pain is relieved for a few hours with an injection into the subtalar joint it suggests that the pain is likely originating from that joint. If the pain is not relieved, then other sources of pathology may need to be explored.

Epidemiology

Osteoarthritis of the ankle and hindfoot is less common than in other limb joints, partly because primary osteoarthritis of the foot and ankle is rare compared to the knee and hip. In a study by Saltzman et al (PMID: 16089071), of 639 patients with ankle arthritis, 70% were post-traumatic, 12% were rheumatoid in nature, and only 7% were idiopathic primary osteoarthritis. Loss of function and disability (limited walking ability, chronic pain, lower limb instability) are long-term consequences of ankle and hindfoot arthrosis.

Differential diagnosis

Many conditions can present like ankle and hindfoot arthrosis. Injuries to the ankle ligaments, tendons and nerves as well as infections or masses may also cause pain in the ankle and should be differentiated from arthrosis of the ankle. Physical examination, imaging studies, and diagnostic injections can be helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Once arthrosis has been established the cause of arthritis should also be established as it may help direct the types of treatment offered.

Before deciding on a diagnosis of arthrosis, it is necessary to rule out the possibility of inflammatory arthritic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, gout, as well as infectious arthritis. Obtaining a personal and family history of arthritis will help to narrow the differential. Lab tests like CBC, ESR, CRP, and immunohistochemistry can also help to identify inflammatory arthritic conditions. In cases where inflammatory or infectious arthritis is suspected, the most effective method for establishing a definitive diagnosis is made using a sample of synovial fluid attained through aspiration of the joint.

Avascular necrosis (also known as osteonecrosis) may present with symptoms typical of arthrosis before overt joint destruction is seen. It is most commonly associated with prolonged use of steroids (such as for people with asthma or other inflammatory conditions) or other medications.

Treatment options and outcomes

Non-operative treatment

Non-operative treatment is usually indicated for patients with mild to moderate arthrosis but may be helpful for patients with any stage of arthritis. It normally involves a variety of treatments including: oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or analgesics, physical therapy, and ankle stabilization (ex. ankle bracing). General exercise and activity modification can also help to prevent pain and progression of symptoms. In moderate-severe cases, intra-articular corticosteroid injection may be necessary to provide short-term pain relief.

Physical therapy is an important aspect of non-operative care early in the course of treatment, to maintain range of motion, strength, and proprioception and thereby decrease the likelihood of leg atrophy over time. Exercise that is relatively non-weight bearing (ex. swimming or cycling) may help maintain an ideal body weight because a high BMI can lead to excessive force on the affected joints.

Ankle support is an important aspect of non-operative care that can minimize painful joint motion and relieve pressure points. There are many ankle support options ranging from simple over-the-counter shoewear modification to ankle braces to custom-molded ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs).

Operative treatment

Operative treatment may be indicated in patients with severe osteoarthritis or when conservative treatment has failed. Several different surgical options exist for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Arthroscopy: Arthroscopic procedures include synovectomy, debridement, loose body removal, excision of bone spurs, and chondroplasty. The effectiveness of ankle arthroscopy in the treatment of arthritis has not been assessed in randomized controlled trial. However, for patients with widespread arthritis it is unlikely to provide long-term relief. Arthroscopy may be helpful for patients with focal arthrosis with a talar OCL (See below).

Tibial osteotomy: Some cases of ankle arthritis stem from a tibial alignment deformity that leads to poor load distribution across the ankle joint. In these cases tibial osteotomy can correct alignment, and improve load distribution across the ankle joint. It is indicated in young patients with a varus or valgus deformity and mild to moderate arthritis caused by a tibial deformity.

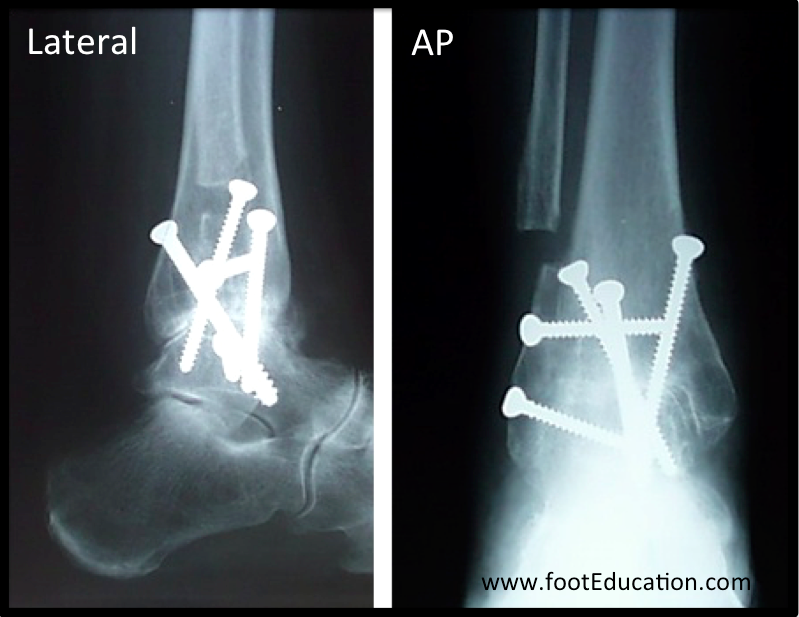

Ankle arthrodesis (Figure 10): Ankle arthrodesis (tibiotalar fusion) is one of the most predictable means of relieving pain from severe ankle arthritis and can be highly effective at doing so. The fusion can be performed either open or arthroscopically to remove the remaining cartilage from the two sides of joint, with additional fixation with plates and/or screws to hold the bones until fusion is achieved. Fusion rates are similar between the two methods, about 80 to 90%, and patient factors such as deformity, vascular or skin compromise, and bone quality often dictate the method used. The major disadvantage of arthrodesis is that it sacrifices the plantarflexion and dorsiflexion movements of the ankle joint. The lack of ankle motion from fusion may be mildly impairing and may also accelerate arthrosis in the subtalar joint. In order to maximize the motion in surrounding joints following fusion, the ankle should be positioned in neutral dorsiflexion and slight hindfoot valgus (heel angled to the outside).

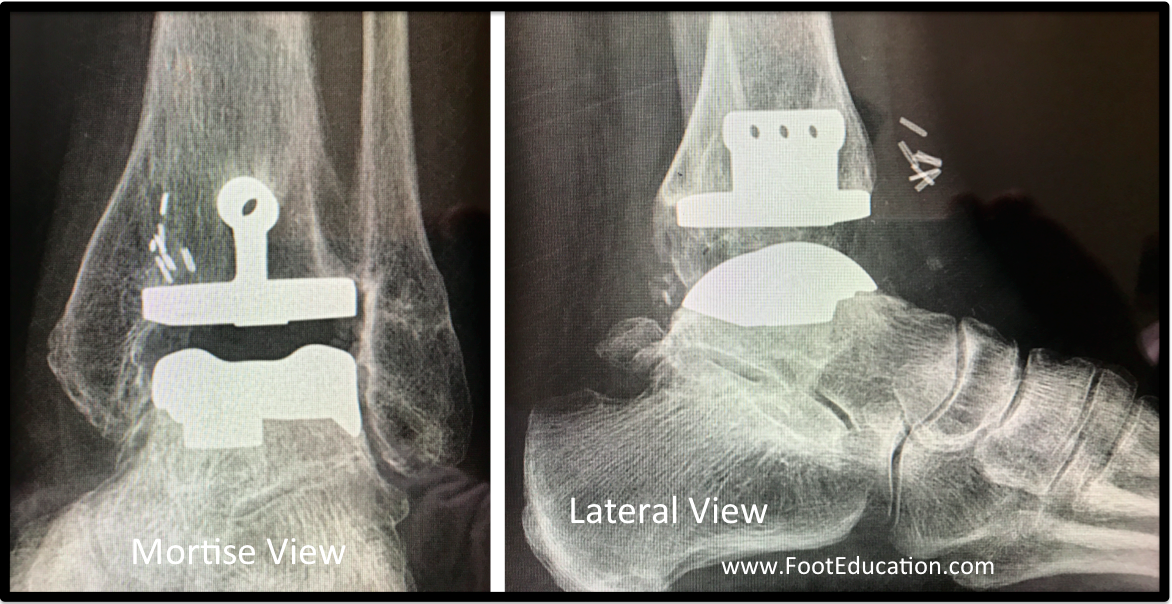

Total Ankle Arthroplasty (TAA): In this procedure, the surgeon replaces the damaged tibial plafond and talus with an artificial joint (Figure 11). It is ideal for a lightweight, sedentary, older patient with end-stage osteoarthritis who has minimal deformity, good range of motion, and a good soft tissue envelope. It has a similar ability to relieve pain as arthrodesis, but with the advantage of preserving motion and possibly relieving stress on adjacent joints. The major disadvantage of ankle joint replacement is that it is mechanical, and will eventually wear out and possibly need a revision replacement. This tends to happen more quickly than in either hip or knee replacements, though recent studies have shown a successful ankle implant retention rate approaching 85-90% at 8-10 years.

Subtalar arthrodesis: Fusion of the subtalar joint (Figure 12) is the best treatment for subtalar arthritis that has failed non-operative treatment. This procedure involves removing the joint cartilage and subchondral bone and attaching the two sides of the subtalar joint with screws or staples. If the two surfaces of the joint do not fully oppose each other then bone graft, either autograft or allograft may be used to fill the void and promote fusion. Again, the tradeoff inherent in any fusion procedure (loss of pain at the price of loss of motion) applies here as well. The procedure can be extended to include the talo-navicular and calcaneo-cubiod joints This is called a “triple arthrodesis.” It is most commonly used to correct deformity within the hindfoot.

Debridement and microfracture: This is the most common approach for treating small (<1.5cm in diameter) talar OCLS. The unstable cartilage is arthroscopically trimmed back and then the bony base is cracked with a pick or drill (“microfractured”) to stimulate bleeding and subsequent formation of a fibrin clot. The fibrin clot that fills the defect undergoes transformation into fibrocartilage (type I cartilage). It is successful in about 90% of cases in which the OLT lesion is less than <15mm. If the articular surface is intact, yet there is a lesion right below it, drilling the talus from distal to proximal, up to, but not through, the articular surface (so called “retrograde drilling”) may be used.

Transplantation of osteochondral tissue: Several transplantation techniques exist to replace lost articular cartilage including osteochondral autograft or allograft transplantation (OATS) and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). These procedures are usually reserved for lesions that have failed debridement and micro fracture, or for larger lesions.

During the OATS procedures, cylinders of cartilage and underlying bone are harvested from the femoral condyle or trochlea and placed within the lesion (not unlike hair plugs). The ACI procedure comprises harvesting autologous chondrocytes, expanding them in a laboratory culture and then re-implanting this larger mass of cells into the lesion, covered by a periosteal patch or collagen matrix.

Risk factors and prevention

Since ankle and hindfoot arthrosis are normally caused by trauma, risk factors are the same as those for ankle and hindfoot injuries including fractures, recurrent ankle sprains, and malalignment. Sports like soccer, football, and basketball have an increased risk of these injuries and therefore have an increased risk of arthrosis.

Some congenital deformities of the foot (e.g. clubfoot) place the patient at increased risk for ankle and hindfoot arthrosis.

Miscellany

Aviator’s astragalus is an old term referring to a displaced talar neck fracture with associated compression fractures of the talus – a pattern of injury seen in World War I aviators who crashed their planes. This term is now only a historical curiosity. These fractures, if displaced have a high rate of osteonecrosis which often leads to either tibiotalar or subtalar arthritis or both.

Key terms

Osteoarthritis, Ankle arthritis, subtalar arthritis, Osteochondritis dissecans, Talar osteochondral lesions, Loose body, Talar dome lesion, Ankle arthrodesis, Ankle arthroplasty, Aviator’s astragalus

Skills

Examine the ankle and hindfoot for tenderness, deformity, and instability. Differentiate ankle and hindfoot arthrosis from other types of arthritis based on history, physical exam, imaging, and other diagnostic testing. Localize arthrosis to the talocrural or subtalar joint.