3 Disorders of the Great Toe

Disorders of the great toe (the hallux, in medical terminology) include degenerative arthritis (hallux rigidus), bunions (hallux valgus), gout, and traumatic conditions (such as sesamoiditis or turf toe).

Structure and function

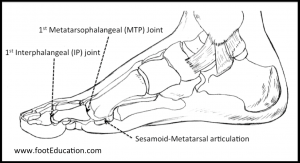

There are three joints of the great toe (Figure 1):

- the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, namely, the articulation between the metatarsal head and the proximal phalanx;

- the interphalangeal (IP) joint between the proximal and distal phalanges; and

- the articulation between the plantar aspect of the metatarsal head and the sesamoids, the two small bones embedded in the flexor hallucis brevis tendon.

It should be noted that a sesamoid bone is one that lives within a tendon; its function is to increase the distance between the tendon and the center of the joint. By so doing, the sesamoid thereby increases the force the tendon applies, by lengthening its so-called ‘lever arm’. The patella is probably the best-known sesamoid.

The first MTP joint

The first MTP joint is a critically important joint. The amount of forces that passes through the first MTP joint and great toe during normal gait varies between individuals depending on foot shape, weight, etc. However, if we consider 6 points of contact in the forefoot (the two sesamoids of the great toe and the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th metatarsal heads) then we can estimate that the great toe on average absorbs a third (2/6) of the body weight. During athletic activities like jogging and running, these forces can approach two to three times body weight.

Processes that can affect the first MTP joint include overuse; wearing shoes that are too tight or ill-fitting; trauma, autoimmune disease; and deposition of uric acid crystals in the joint (gout).

Hallux Rigidus (arthritis of the big toe)

In hallux rigidus (Figure 2), it is thought that overuse damages the joint surfaces and the nearby soft tissue surrounding the joint. This term is used to describe arthritis of the joint; the name comes to mind because in the MTP joint the osteophytes growing from dorsal aspect of the first MT head impede motion (making the joint rigid) in a way that is not typically seen when osteophytes form near other joints around the body. Of course, the signs and symptoms of the condition include all those of arthritis, not just the rigidity of the joint.

Hallux Valgus (Bunions)

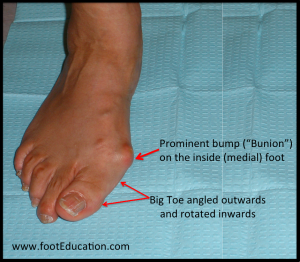

Like hallux rigidus, which is named by one prominent feature, hallux valgus is also designated by one major finding (the valgus deformity of the MTP joint), though it actually comprises several (Figure 3). A valgus deformity is one in which there is deviation at a joint such that the distal bone points away from the midline; in the knee, for example, valgus produces a “knock-knee” configuration. Thus, in hallux valgus there is a lateral deviation of the phalanx (towards the other 4 toes). Beyond that, though, there is also a medial deviation of the first metatarsal along with soft-tissue enlargement of the first metatarsal head. The MTP joint could remain congruent, but eventually can subluxate creating a non-congruent deformity. When there is a loss of congruence, the pull of muscles accentuates the deformity further, and the proximal phalanx progressively moves laterally and the metatarsal medially; the dorsomedial capsule attenuates and the abductor hallucis tendon slides under the metatarsal head. This subluxation of the abductor hallucis tendon pulls the hallux into pronation. In time, there is also lateral subluxation of the sesamoids. In late stages, the extensor hallucis contracts, causing both extension and lateral deviation of the great toe.

Gout (Podagra)

Gout is a painful arthritic condition that can affect any joint, but commonly involves the first MTP joint. Gout occurs when uric acid (urate) crystallizes in the synovial lining of the involved joint. Once in the joint, these crystals induce synovial macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-1 (IL-1). The urate crystals also induce neutrophils to migrate to the joint, increasing the inflammatory process.

Patients with longstanding gout may have masses of urate crystals deposited in soft tissue, cartilage and bone; these are known as “tophi” (singular: tophus). These tophi consist of central deposits of monosodium urate surrounded by fibrous and inflammatory rinds. Small tophi may be asymptomatic; large ones can be painful, even when there is no burst of inflammatory activity.

Turf Toe

Turf toe is an acute injury to the MTP joint that occurs when the great toe is forced upward. This produces an injury to the plantar plate. The classic mechanism is an athlete jamming his or her foot against a hard surface.

Sesamoiditis

Sesamoiditis is a general term for painful symptoms associated with either one or both of the sesamoid bones. The tibial (medial) sesamoid is subject to more force and thus more prone to injury. The mechanism of injury is usually associated with repetitive, excessive loading of this area of the foot, but it can also be due to trauma or forced dorsiflexion. Often patients will have a higher arched foot, causing the sesamoids to be subjected to great force with each step. The resulting pathology may include chronic soft-tissue injury, stress fracture of one of the sesamoids or a sesamoid that never heals (nonunion) after injury, or cartilage damage (arthritis) between the sesamoid and the first metatarsal head.

Patient presentation

Patients with hallux valgus present with a prominent bump on the medial side of the MTP joint. Symptoms range in severity from none at all to severe discomfort aggravated by standing and walking. There is no direct correlation between the size of the bunion and the patient’s symptoms – some patients with severe bunion deformities have minimal symptoms, while patients with mild bunion deformities may have significant symptoms. Symptoms are often worsened by shoes with a narrow or stiff toe box.

Physical examination reveals a bony prominence at the medial aspect of the first metatarsal head. The great toe is deviated laterally and often rotated slightly. In mild and moderate bunions, a subluxated MTP joint may be repositioned back to a neutral position (reduced); in more advanced disease, especially if there are arthritic changes in the first MTP joint, the joint cannot be fully reduced. Patients may also have a callus at the base of their second toe under their second metatarsal head in the sole of the forefoot.

Patients with hallux rigidus will typically present with pain, stiffness, and swelling in the first MTP joint (Figure 4). The symptoms are aggravated by repetitive dorsiflexion of the MTP joint (upward movement of the big toe), running, for example. Swelling usually occurs along the top (dorsal) half of the joint, and will frequently be associated with bone spur formation recognized as a “new prominence” by the patient (Figure 6B).

In the early stages of hallux rigidus, there is pain only at ends of the range of motion. In the late stages, there is a loss of motion, especially dorsiflexion, and pain even within the short arc.

Patients may report symptoms from the dorsal prominence (osteophytes). As the condition progresses, patients can attempt to take pressure off the great toe by putting more weight on the outside of the foot as they walk. This may cause metatarsalgia, pain in the forefoot, or in rare instances a Jones fracture of the 5th metatarsal base.

Physical examination will reveal limited and often painful motion in the big toe joint sometimes with crepitus. Prominent osteophytes on the dorsal aspect of the joint are usually visible and palpable. It is very common to see these findings in both feet, although one foot is usually more symptomatic than the other. Tenderness to touch is common dorsal to the swollen MTP joint.

Patients presenting with sesamoiditis will often report a recent increase in repetitive weight-bearing activities that suddenly overload this joint. Rarely is a major acute traumatic event the cause for the problem, although it certainly can be. Pain is typically described as sharp and severe enough to induce a limp. Some patients report that it is especially uncomfortable to walk with barefeet or on hard surfaces. The most common forms of sesamoiditis, by far, presents with a slow, steady onset of patterned pain beneath an otherwise normal looking big toe, which is worse with weight bearing and better with offloading activity. Patients can almost always point to the site of discomfort, which is directly beneath one, or both, of the sesamoids.

It is also common for patients who suffer from sesamoiditis to have high arched feet, due to the higher loads placed on the ball of the foot with this anatomy. Range of motion of the great toe is often normal; marked loss of motion of the big toe, or pain on the top of the great toe is more consistent with a diagnosis of hallux rigidus.

Patients with gout often report a relatively sudden onset of severe symptoms including pain, swelling, and redness. Gout may involve almost any joint in the body, but in 75% of cases, gout affects the first MTP joint (hence the classic name for gout, podagra, which means “seizure” of the foot).

Turf toe injuries result in pain on the plantar surface at the base of the first MTP joint. They usually occur after an acute injury: an athlete will report changing direction suddenly on the playing field, with the great toe forced upwards as the foot is planted on the ground. With enough force, the capsule on the undersurface (plantar aspect) of the great toe will be torn either partially or completely. Patients will complain of pain in the great toe, noticeable swelling, a limp, and an inability to run on the foot. If the capsule is significantly torn the great toe joint may be noted to be unstable.

Objective Evidence

Hallux valgus deformity is usually obvious upon physical examination, but it is also easily demonstrated on plain X-ray (Figure 5). A weight-bearing foot series should be obtained to assess forefoot alignment, including the presence of lesser toe deformity, and evaluated for degenerative changes at the IP, MTP, and metatarsal cuneiform (MTC) joints. A weight-bearing anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph assesses hallux valgus angle (HVA), intermetatarsal angle (IMA), MTP joint congruency, and sesamoid position. This evaluation allows for classification and preoperative planning. The lateral radiograph should be assessed for plantar gapping at the 1st MTC joint and dorsal translation of the 1st MT relative to the cuneiform that is indicative of instability.

When hallux rigidus is suspected, weight-bearing foot x-rays should be obtained to demonstrate the presence and extent of MTP joint space narrowing, and identify the location and size of bone spurs. There may be squaring of the metatarsal head on the anterior-posterior (AP) view (Figure 6A). The lateral view will often show a prominent dorsal bone spur (Figure 6B).

The only definitive way to diagnose an acute gouty attack is to aspirate the joint. Patients with gout will demonstrate synovial fluid leukocytosis (predominantly neutrophils) and the presence of negatively birefringent, needle-shaped crystals viewed using a polarizing microscope. Even with these findings, a simultaneous infection is not definitively excluded. Accordingly, synovial fluid aspirated for gout should always be assessed for infection by Gram stain and culture.

X-rays in turf toe injuries are usually negative, as this injury predominately affects the soft-tissue around the MTP joint. However, plain x-rays should be reviewed to rule out other injuries such as sesamoid fractures and other fractures involving the great toe. A stress x-ray or fluoroscopy may demonstrate excessive movement (instability) of the MTP joint when it is stressed. An MRI will reveal evidence of the soft-tissue (capsular) injury.

When sesamoiditis is suspected, plain x-rays of the foot allow visualization of the two sesamoids and how they sit anatomically beneath the first MTP joint. Fractures, subluxations, dislocations, osteochondrosis, or avascular necrosis affecting the sesamoid(s) can usually be diagnosed on these plain x-rays. It is possible to see fragmentation of the sesamoids that is not pathological: so-called bipartite (two pieces) or multipartite (many pieces) sesamoids. One way to help differentiate a sesamoid fracture from a bipartite sesamoid is by comparison to the contralateral side, as bipartite sesamoids are often bilateral whereas a true fracture is usually not.

When an accurate diagnosis cannot be made and certain possible problems still cannot be ruled out, an MRI scan can usually accurately differentiate between these various pathologies.

Epidemiology

The most common disorder of the great toe is hallux valgus. According to a meta-analysis performed by Nix et al. (PMID:20868524), the prevalence of hallux valgus in patients aged 18-65 is 23% and 35% in patients older than 65 years. In addition to the elderly, hallux valgus is more prevalent in females. There appears to be a hereditary component: a majority of patients have a first-degree family member who also has hallux valgus with the condition.

According to Shereff and Baumhauer, hallux rigidus affects 2.2% of the population 55 years or older (PMID:9655109). It is the second most common condition affecting the big toe after hallux valgus. The condition is often bilateral, and the average age of onset ranges between 12 and 57 years, although it is more common in the older population.

According to Boike et al., sesamoid injuries account for 9% of foot and ankle injuries and 1.2% of running injuries (PMID:21669339). Chronic sesamoid conditions, like sesamoiditis, usually occur in active patients. Sesamoiditis is more prevalent in teens and young adults than older patients.

According to Childs, turf toe prevalence is increasing due to more athletic fields being covered in artificial turf and increased flexibility in the toe-box of athletic shoes (PMID:16900075). Turf toe is seen most often in football players, although athletes participating in basketball, soccer, dancing, tennis, volleyball, and wrestling are at elevated risk. Turf toe is not more prevalent in any one age-group, sex, or ethnicity.

Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis and its prevalence is on the rise. Putative causes of this rise include the rising prevalence of metabolic syndrome, the aging of the population, and an increase in chronic kidney disease. Gout before the age of 50 is almost exclusively a male disease. At menopause, serum uric acid rises; consequently, gout is present in the older female population as well. Gout is distinctly rare in children, but may occur when genetic mutations affect urate metabolism. The overall prevalence of gout in the US is estimated to be about 3%, but is 10% or greater in older adults.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for pain at the first MTP joint includes not only bunions (hallux valgus), arthritis (hallux rigidus), gout, and sesamoiditis, but infection, stress fracture, tendon disorders, non-neoplastic soft-tissue masses, and rarely neoplastic soft-tissue and bone neoplasms.

Hallux valgus is fairly easy to diagnose on physical exam. However, it is important to note that asymptomatic hallux valgus can be present along with a second painful condition: a patient with hallux valgus may also suffer from hallux rigidus, sesamoiditis, turf toe, or gout. Therefore, it is important to take a detailed clinical history upon patient presentation even if a hallux valgus deformity is obvious.

While hallux valgus is a fairly obvious diagnosis, sesamoiditis is often a diagnosis of exclusion. It should be considered in active patients who have recently changed their activity level or shoe-wear. Sesamoiditis pain is variable, but often patients will be able to point to the site of pain as being underneath one or both sesamoid bones. The differential diagnosis for this type of pain includes fractures, subluxations, dislocations, osteochondrosis, or avascular necrosis. These can usually be distinguished by plain x-ray.

Hallux rigidus, like sesamoiditis, is also characterized by pain with dorsiflexion and shifting weight laterally during ambulation to avoid toe-off. However, hallux rigidus usually develops over a longer period of time than sesamoiditis. Furthermore, the dorsal aspect of the first MTP joint is normally tender upon palpation in patients with hallux rigidus, while the plantar aspect is tender in patients with sesamoid disorders. Additionally, these two disorders can be differentiated using imaging, as hallux rigidus is characterized by osteophytes on the dorsal aspect of the MTP joint with or without joint space narrowing, while these features are absent in sesamoid disorders. Hallux rigidus must also be differentiated from gout.

Differential diagnosis of acute gout depends on the patient history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. The most important alternative diagnosis to consider, particularly in monoarticular attacks, is septic joint because infection can rapidly and permanently damage joints. Other crystals, particularly calcium crystals, can cause attacks mimicking gout. Gout can also mimic virtually any inflammatory arthritis, depending on the pattern of presentation. For example, rheumatoid arthritis may need to be considered if the gouty attack is polyarticular and involves the hands.

When an athlete presents with an acute injury of the first MTP joint following forced hyper-extension of the hallux, the diagnosis is almost certainly turf toe. However, turf toe is a broad category that encompasses different severities of capsular injury, from attenuation of the capsule (plantar plate) to a complete tear. Plain x-rays should be reviewed to rule out other injuries such as sesamoid fractures and other fractures involving the great toe.

Red Flags

Imaging studies should be performed in most cases of first MTP joint pain, especially with recalcitrant pain following conservative treatment, in facilitate an accurate diagnosis and plan future treatments accordingly.

A single gout attack is extremely painful but usually self-limited. A missed diagnosis at that time will be of little long-term consequence. However, a missed diagnosis of an infected joint can be catastrophic; and because gout and infection are often clinically indistinguishable, diagnostic joint aspiration should almost always be performed.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

Non-operative treatment of most causes of great toe pain is usually successful. Conservative treatment strategies include:

- Activity modification: limiting the extent of weight-bearing activities such as standing and walking in the short and intermediate term decreases the repetitive load and subsequent irritation to the joint and surrounding tissues.

- Shoe wear modification: Stiff-soles shoes with a soft insert and a wide accommodative toe box can be very helpful in alleviating repetitive irritation and pain from most common great toe conditions.

- Anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs): Short-term use of anti-inflammatory medications can help improve symptoms.

- Steroid injection: Corticosteroid injections of the 1st MTP joint may be beneficial in recalcitrant cases of hallux rigidus, gout and other conditions where there is marked painful swelling and inflammation of the great toe joint.

The vast majority of great toe problems can be managed non-operatively. The primary indication for operative intervention should be pain that is not relieved by appropriate non-operative management.

Surgical treatment of Bunions (hallux valgus)

Operative treatment for hallux valgus is often requested for cosmetic reasons, but sharing with patients the prolonged recovery time and risks of complications are conveyed, may dissuade them. There are many different surgical treatments for hallux valgus described in the orthopaedic literature. The type of procedure chosen depends on the severity of hallux valgus, co-morbid conditions, and the preference of the surgeon. Some of the common procedures include removal of the medial eminence; a distal metatarsal osteotomy (chevron) with tightening of the medial capsule; a proximal metatarsal osteotomy; great toe fusion (1st MTP joint arthrodesis); or resection arthroplasty (removal of the proximal aspect of the proximal phalanx). Often, up to 12 months are required before maximal recovery is achieved. Post-surgical complications are not uncommon and may include: wound healing problems, infection, nonunion, local nerve injury, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism (PE). Additionally, the deformity may recur, or a new deformity may form at the osteotomy, requiring an additional surgery.

Surgical treatment of Great Toe Arthritis (hallux rigidus)

Operative treatment for hallux rigidus may be indicated when non-operative treatments fail. Surgical treatment of hallux rigidus includes: a 1st MTP joint dorsal cheilectomy (bone spur removal); fusion of the first MTP joint, and first MTP joint arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty (first MTP joint replacement or partial joint replacement). The dorsal cheilectomy procedure is effective only for patients who have arthritis involving just the dorsal aspect of the first MTP joint; it is not indicated in patients with arthritis involving the entire joint. Recurrence of pain is a not-infrequent complication of cheilectomy. If this is found, the other two surgical options should be considered. Fusion of the great toe joint offers predictable pain relief. One of the defining features of severe hallux rigidus is a loss of 1st MTP joint motion so from a functional point of view loss of joint motion following a fusion is often not a major issue. Joint replacements of the 1st MTP can provide good short and intermediate term pain relief and function. However, eventual failure of the implant can make revision surgery very challenging.

Surgical Treatment of Sesamoiditis

Recalcitrant sesamoiditis that does not improve with 6 months of non-operative treatment can be considered for operative removal of the sesamoids, though most patients recover before that deadline. Excising only the painful sesamoid bone may lead to destabilization of the joint with the development of a subsequent hallux varus or valgus deformity depending on which sesamoid is removed.

Surgical Treatment of Turf Toe Injuries

In turf toe injuries where there is complete tearing of the plantar soft-tissues of the great toe (ex. great toe dislocation) surgical repair is indicated. Additionally, turf toe injures resulting in partial tearing of the plantar capsule that do not adequately recover with conservative treatment may benefit from debridement (e.g., cleaning out cartilage debris) and repair of the torn plantar capsule. Recovery can be prolonged: 6 weeks of limited weight-bearing to allow the capsular repair to heal; 6 weeks of controlled rehabilitation in a boot or stiff soled shoe; and 6 or more weeks of sports-specific exercises. It is also not uncommon to have some residual symptoms even after a seemingly successful surgery. Unfortunately, for some athletes, a severe turf toe injury may be a career ending injury.

Treatment of Gout

Treatment of acute gout focuses on suppressing inflammation. Three classes of agents are used: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, and colchicine. All are effective; the choice of agent depends on which will be best tolerated in the individual patient. Intra-articular glucocorticoid injections are effective but should be avoided until infection is definitively excluded. Changing the dose of urate-lowering drugs during an acute attack should generally be avoided because acute urate shifts may worsen the attacks.

For patients with established gout (two or more attacks/year) who are between attacks, urate-lowering should be initiated to reduce the urate burden and the risk of both attacks and tophi. First-line agents include allopurinol and febuxostat, which block urate production by inhibiting the synthesis enzyme xanthine oxidase. In contrast to targeting urate production, probenecid promotes urate excretion from the kidneys. All patients starting urate-lowering therapy must receive anti-inflammatory prophylaxis (usually colchicine) for 6 or more months, since urate lowering transiently increases the risk of gouty attack. The goal is to drive the serum urate level to <6.0 mgs/dL (lower to resolve tophi).

Risk factors and prevention

Risk factors for hallux rigidus include an elevated first metatarsal and/or a supinated forefoot leading to dorsal jamming at the 1st MTP joint. These risk factors are not really subject to modification. Wearing good comfort shoes (e.g., the correct size, soft uppers, and a stiff sole that limits motion of the first MTP joint) and maintaining a healthy weight, may help in patients who are predisposed to develop hallux rigidus.

Patients with hallux valgus often have a positive family history. The majority of patients with hallux valgus have a first-degree relative who has had a bunion, flatfoot deformity, or significant clawing of their lesser toes. Wearing tight or ill-fitting shoes may contribute to symptoms related to the hallux valgus deformity, but the evidence on causality is not conclusive.

The main risk factor for disorders of the sesamoid is having a higher arched foot. People with high arches that may be predisposed to sesamoiditis may be able to prevent this by wearing shoe inserts that reduce the stress on the sesamoids.

According to Childs, risk factors for turf toe include participating in athletics on artificial turf fields, playing certain sports that predispose to the injury (football, soccer, basketball, wrestling, dancing, tennis, and volleyball), foot pronation, increased toe box flexibility, flat feet, hallux degenerative joint disease, and prior first MTP joint injury (PMID:16900075). Therefore, turf toe injuries may be reduced by wearing shoes with a stiffer sole and limiting the amount of play on artificial turf fields.

Multiple risk factors promote hyperuricemia and subsequently gout. Diets rich in purines, or high in alcohol or fructose (promoting purine turnover and urate synthesis), can raise serum uric acid (sUA). Diseases of high cell turnover such as leukemia and lymphoma also promote hyperuricemia (secondary overproduction). Diuretics and certain other drugs can inhibit renal urate excretion and promote hyperuricemia. Obesity is also associated with hyperuricemia, but the relative contributions of diet versus adiposity are unclear. Nonetheless, weight loss reduces sUA and is advisable in overweight gout patients.

Miscellany

Turf toe was so named as the injury became more common with the increasing popularity of artificial turf over natural grass.

Sesamoids are so named because they are thought to resemble sesame seeds.

Key terms

Hallux valgus, Bunion, Hallux rigidus, Great toe arthritis, Gout, Sesamoiditis, Turf toe, Podagra

Skills

Perform a thorough musculoskeletal history and physical. Identify pathology on radiographs.