6 Plantar Fasciitis

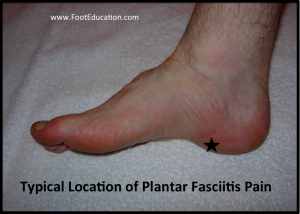

Plantar fasciitis is a common source of pain under the heel (Figure 1). The etiology of the condition is thought to be overuse, with traction and shear forces applied to the plantar fascia causing microscopic injuries to the tissue. It is not a purely inflammatory condition as the “itis” suffix would suggest. Classic findings of plantar fasciitis include pain and tenderness in the heel at the junction of the plantar fascia and the medial calcaneal tuberosity. Symptoms are usually worse with the first few steps in the morning (so-called “start up pain”). Helpful treatments include stretching of the calf muscles and the plantar fascia itself and the use of orthotics with a medial arch support.

Structure and function

The plantar fascia is a sheet of fibrous tissue (technically termed an aponeurosis) running along the sole of the foot from the calcaneus to the base of the proximal phalanges, with fibers merging with the dermis, transverse metatarsal ligaments, and flexor tendon sheaths as well. The plantar fascia is mostly inelastic, with minimal elongation.

Weight-bearing forces tend to flatten the medial longitudinal arch as forces are applied to the foot. The plantar fascia prevents this collapse, by maintaining the distance between the calcaneus and the metatarsals. Note that the insertion of the plantar fascia is on the toes; hence dorsiflexion of the toes pulls on the plantar fascia, winding it under the metatarsals and thereby elevating the arch, a so-called “windlass” effect.

Plantar fasciitis is thought to be produced by overuse, creating a chronic microscopic injury to the plantar-medial origin of the plantar fascia. A heel spur is commonly found on x-ray, but is neither a sensitive nor specific finding. Only 50% of patients with heel pain will have heel spurs and about 15% of people with asymptomatic feet will have them. Accordingly, it is likely that the spur is not causing the condition. Further, cadaveric dissections have demonstrated that the spur from the calcaneus is within the flexor tendons, rather than the plantar fascia itself.

Histologic findings in plantar fasciitis includes tears in the fascia, myxoid degeneration, angiofibroblastic hyperplasia, and collagen necrosis and not inflammation per se. However, inflammation could be part of the healing process.

Patient presentation

Healing of micro-trauma is thought to cause tightening of the plantar fascia when the patient is at rest, especially as the foot and ankle assume a plantarflexed position at night. Upon ambulation, when the foot and ankle forced into a neutral and dorsiflexed position, the healing tissue is strained. Thus, the classic presentation of plantar fasciitis as an especially sharp pain with the first few steps in the morning or after prolonged rest. This pain is localized to the plantar medial aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity (Figure 1). It will often improve after some movement or stretching. However, it will tend to recur and worsen as the day progresses, particularly if the patient has had prolonged periods of significant weight-bearing activities such as walking or standing.

The foot and ankle physical exam should include inspection of the patient’s stance, foot shape, and gait; full neurologic evaluation; and identification of any areas of tenderness, especially at the medial plantar aspect of the heel. In some patients, dorsiflexion of the toes may exacerbate the pain via the windlass effect.

Objective Evidence

Plantar fasciitis is diagnosed by history and physical examination, but x-rays may help rule out other diagnoses. A lateral weight-bearing view of the foot will often demonstrate a calcaneal heel spur, though this should be considered an incidental finding. As previously noted the presence of a heel spur does not directly correlate with symptoms.

Diagnosis of classic plantar fasciitis requires only a good history and physical exam. However, in atypical presentations or when symptoms are recalcitrant and other diagnoses are being considered, further imaging studies may be indicated. An MRI or a triple-phase bone scan can differentiate plantar fasciitis from a calcaneal stress fracture – a much less common cause of heel pain. An MRI may also be used to rule out other uncommon causes of heel pain such as tumors and infection. Ultrasound is less expensive than an MRI and provides no radiation exposure but requires specific expertise that many physicians lack. Typical ultrasound findings include a thickened, hypoechoic plantar fascia with soft-tissue edema.

Except in rare instances where an inflammatory condition is suspected, laboratory studies are not indicated in the workup of patients with plantar heel pain. Similarly, in the uncommon situation where neurological symptoms are suspected, nerve conduction studies may help exclude local nerve entrapment (medial plantar nerve).

Epidemiology

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain. Patients are usually 40-50 years of age. Plantar fasciitis may be bilateral in some patients although one heel is usually more painful than the other.

Differential diagnosis

Plantar fasciitis is the most likely cause of heel pain but other entities such as overload heel pain syndrome, heel pad atrophy, entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (Baxter’s nerve), tarsal tunnel syndrome, calcaneal stress fracture and seronegative inflammatory disease can also lead to heel pain.

Patients with overload heel pain syndrome will have pain that is centrally located in the heel rather than towards the inside of the heel pad such as is typical in plantar fasciitis. Certain foot patterns such as high arched feet, relative weakness of the calf muscle, or dysfunction of the Achilles tendon may be predisposed to overloading the heel with resulting symptoms.

Marked pain after a sudden increase in the patient’s level of activity or training should prompt a work-up to rule out a calcaneal stress fracture. Infection or neoplasm are more likely when the plantar heel pain is present at night, especially when accompanied by unplanned weight loss, fevers or chills. These are, in general, unlikely diagnoses.

Burning pain is not typical of plantar fasciitis and may suggest nerve irritation as a source of the pain: Baxter’s neuritis (compression of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve, also known as the inferior calcaneal nerve); peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy.

Red flags

Any deviation from the classic history for plantar fasciitis should be a red flag to consider other diagnoses.

Treatment options and Outcomes

The vast majority of patients will have their symptoms resolve with or without treatment over a period of 6 months. Recovery can be accelerated with a program of calf and plantar fascia stretching, activity modification to avoid precipitating activities, and comfort shoewear. Formal physical therapy, immobilization via cast or boot, steroid injections, and rarely extracorporeal shock wave therapy may also be employed.

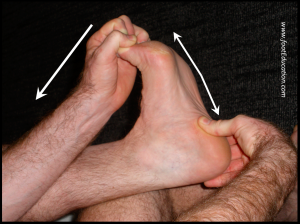

A plantar fascia specific stretching program is highly beneficial in treating plantar fasciitis (Figure 2). This is performed by gently pulling the ankle and toes into dorsiflexion. This produces tension in the plantar fascia. The stretch position should be held for 10 seconds and repeated 10 times. The timing of when this is performed is important. It should be done prior to the first step in the morning and during the day before standing after prolonged inactivity.

Calf stretching should be performed with the knee straight so that the gastrocnemius (which originates on the femur) is stretched. It is also important to internally rotate the foot to lock out the subtalar joint during the stretch. For patients with plantar fasciitis it is usually best to ask them to rotate their foot inward with the heel on the ground until the heel pain diminishes, then stretch. Six sets of 30 seconds per side done daily is recommended.

With resolution of the heel pain symptoms, it is important to continue calf stretching and plantar fascia stretching on a semi-regular basis so as to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Any activity that has recently been started, such as a new running routine or a new exercise at the gym that may have increased loading through the heel area, should be stopped on a temporary basis until the symptoms have resolved. At that point, these activities can be gradually started again.

A soft, over-the-counter orthotic with an accommodating arch support might be helpful. Evidence supporting the need for a custom orthotic is lacking. Shoes with a stiff sole and rocker-bottom contour off-load the plantar fascia at its origin and likewise may be effective.

Anti-inflammatory medication may ameliorate symptoms. Corticosteroid Injection can give temporary relief but may lead to atrophy of the fat pad. Injections of preparations of autologous blood (ex. plasma rich protein – PRP) have been described but lack high quality supportive evidence.

A plantar fascia night splint (Figure 4) that keeps the ankle in a neutral position, perpendicular to the foot, while the patient sleeps, can be helpful in alleviating the significant morning symptoms. Avoiding the position of plantar flexion can prevent some of the shortening of the fascia that occurs at night.

Surgery is rarely indicated in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Only patients who have persistent symptoms despite adhering to the non-operative treatment for a minimum of 6 months should be considered for surgery. Endoscopic or open partial plantar fasciotomy involves removal of the injured area of the plantar fascia. Although this procedure has produced good results in some cases, complete release of the plantar fascia may lead to a flat foot and chronic foot pain. Therefore, it is recommended that less than 40% of the plantar fascia be released (though an appropriately conservative release may limit the effectiveness of the procedures).

A surgical recession of the gastrocnemius (ex. Strayer procedure) theoretically should help resolve the symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis, as gastrocnemius contracture is a known risk factor for the development plantar fasciitis. There are only limited studies assessing the long-term effectiveness of this procedure.

Risk factors and prevention

Risk factors for plantar fasciitis include a job or lifestyle associated with prolonged standing, excessive body weight, increasing age, a change in activity level, Achilles tightness, and a stiff calf muscle (gastrocnemius). A flat foot or a high arch deformity (pes planus and pes cavus, respectively) can increase loading of the plantar fascia and increase the risk of developing plantar fasciitis. However, any foot type can develop this condition.

Miscellany

Fascia and political Fascism are related words. A fascia is of course connective tissue, typically that wraps around muscle fibers. Fascism comes from the Italian word fasci, political groups or guild, itself derived from the Latin word fascis, meaning “bundle.”

Key terms

plantar fascia, plantar fasciitis, calcaneus, Achilles tendon

Skills

Learn how to instruct patients on stretching the plantar fascia and gastrocnemius.