10 Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a condition that causes pain in the foot due to traction and compression of the tibial nerve within the tarsal tunnel. The tarsal tunnel is located in the ankle behind the medial malleolus, superficial to the bones (calcaneus and talus) and covered by the flexor retinaculum. When the posterior tibial nerve is irritated presenting symptoms include pain, numbness and paresthesias. Tarsal tunnel syndrome can be caused by space occupying lesions (such as a ganglion cyst); more commonly it is caused by deformities of the foot and ankle that stretch the nerve and decrease the volume of the tarsal tunnel.

Structure and function

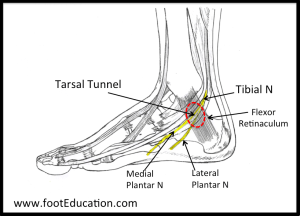

The tarsal tunnel is the space located posterior and inferior to the medial malleolus; medial to the calcaneus and talus, and deep to the flexor retinaculum. The contents of the tarsal tunnel, from anterior to posterior, include the tibialis posterior tendon, the flexor digitorum longus tendon, the posterior tibial artery, tibial nerve, and flexor hallucis longus (Figure 1). The tibial nerve divides within the tarsal tunnel into the calcaneal nerve coursing towards the heel and the medial and lateral plantar nerves which supply the bottom of the foot.

The flexor retinaculum – also known as the laciniate ligament – covering the tunnel ensures that the contents of the tunnel remain within it, but may be a source of abnormal compression if the anatomy is disturbed.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is thought to be caused by repetitive traction on the nerve leading to scarring. In this sense the etiology of the condition is different than carpal tunnel in the wrist which is primarily a compression-related phenomenon. However, extrinsic compression from a bone spur, ganglion, or synovial proliferation from a tendon disorder, although much less common, may also cause tarsal tunnel syndrome.

As pressure increases with the tarsal tunnel, blood flow decreases and the nerve becomes ischemic. Malfunction of the nerve, in turn, yield the presenting symptoms of tingling and numbness.

Patient presentation

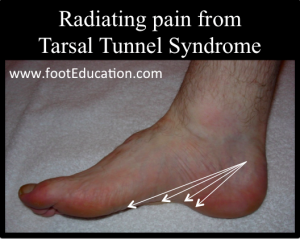

Patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome typically complain of numbness in the foot radiating to the big toe and the first 3 toes, pain, burning, electrical sensations, and tingling over the base of the foot and the heel. A broader area of symptoms suggests either nerve entrapment proximal to the tarsal tunnel, or a generalized neuropathy.

Standing, especially in patients with associated flatfoot deformities, causes increased traction and compression on the nerve within the tarsal tunnel. As a result, patients may report that prolonged standing and walking makes their symptoms worse.

Compression of the tibial artery within the tarsal tunnel may cause ischemia to the intrinsic muscles of the foot with painful cramping accordingly.

Objective evidence

On physical examination, patients will often have a flat foot.

Palpation over the tarsal tunnel will produce localized pain (tenderness) as well as radiating pain into the sole of the foot (Figure 2). This latter sensation with percussion of the nerve is called a “Tinel’s sign,” though this is not a true objective sign but a vocalized subjective symptom. Sensory examination of the foot may reveal some decreased sensation on the sole of the foot, although in most patients this is not the case.

Muscle atrophy and claw-toe deformities suggest chronic compression.

Nerve conduction studies will often show a decrease in conduction velocity in the tibial nerve precisely as it courses under the flexor retinaculum.

Weight-bearing x-rays of the foot should be assessed to exclude fractures and bone spurs, as well as malalignment (for example, hindfoot varus or valgus) that can alter the geometry of the tarsal tunnel.

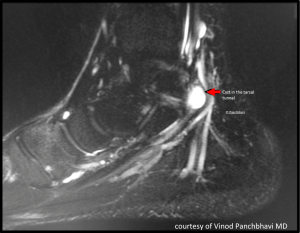

CT scans, ultrasound or MRI might be needed to rule out space-occupying lesions within the tarsal tunnel (Figure 3). These include ganglions, lipomas, or (rarely) accessory muscles. Detection of a mass on imaging studies is uncommon, but critical to rule out. When a space-occupying lesion is present the patient is unlikely to improve clinically until the mass is removed. By contrast, without a mass, surgery is rarely indicated.

Epidemiology

The National Institutes of Health’s website on rare diseases says, “The incidence and prevalence of tarsal tunnel syndrome is unknown.” (https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7733/tarsal-tunnel-syndrome). The very fact that tarsal tunnel syndrome is included by the NIH on its list of “rare” conditions means that it affects fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome can be considered to have two components. The first is the true differential diagnosis – that is, the list of conditions that may instead be responsible for a presentation similar to that of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Beyond that, once the diagnosis is established, there is a second differential diagnosis list to consider, namely, the other conditions that may be responsible for causing the tarsal tunnel syndrome itself.

In the first category, the main considerations are lumbar radiculopathy and peripheral neuropathy (most often caused by diabetes). A complex regional pain syndrome (formerly known as Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy) could be responsible as well, though the findings in complex regional pain syndrome would almost certainly extend beyond the distribution of the tibial nerve.

Conditions that may be the cause of tarsal tunnel syndrome include trauma (fracture fragments causing compression or ligament injury causing instability and traction on the nerve); space-occupying lesions such as ganglion cyst, benign tumors, swollen tendons or varicose veins; ankle deformities such as pes planus (flat foot).

In addition, there are associated conditions that are commonly found in patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome owing to a similar etiology. Acquired adult flatfoot deformity (posterior tibial tenosynovitis) and plantar fasciitis tend to occur in patients with flatfeet due to repetitive traction loading of these structures. Similar traction forces often produce tarsal tunnel like symptoms.

Red flags

There are no true “red flags” with tarsal tunnel syndrome, though the presentation of tarsal tunnel syndrome-like complaints may be the first clue of an otherwise undetected diagnosis of diabetes, peripheral artery disease or disc herniation/spinal stenosis.

Treatment options and outcomes

If the patient has confirmed tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by a space-occupying lesion, that offending structure should be removed. Beyond that, the vast majority of patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome can (and should) be treated non-operatively. Only with a prolonged failure of non-operative treatment in a patient with positive nerve conduction studies and severe symptoms should surgical release be considered.

The primary non-operative treatment approach to treating tarsal tunnel syndrome is to attempt to decrease the repetitive traction injury across the nerve and the other structures in this area of the foot. In this regard, treatment is quite similar to that for acquired adult flatfoot deformity and plantar fasciitis.

Comfort shoes designed to disperse the force more evenly across the foot can be very helpful. Weight loss should be recommended to patients who need it.

A prefabricated orthotic with a supportive arch will help to disperse the force more evenly across the foot may also be helpful.

Physical therapy including exercises designed to stretch the calf muscle and thereby indirectly decrease the load through this area of the foot may also be helpful.

Limiting walking can reduce symptoms but may impede weight loss (and be impractical for other reasons). Advice to limit standing, an activity which can produce symptoms with fewer health benefits than those involving motion, may be more apt.

Corticosteroid injections may help to decrease the swelling around the nerve in the short and intermediate term. However, it is unclear what effect they have in the long term. In addition it is possible to injure the nerve during the injection process.

Operative treatment can be considered in rare cases. Primary resection of space-occupying lesions causing isolated tarsal tunnel syndrome can relieve symptoms reliably, provided that the nerve is neither scarred nor damaged prior to surgery. Beyond that, operative treatment includes tarsal tunnel release and other procedures to correct deformity causing compression may be used.

Tarsal tunnel release comprises release of the flexor retinaculum and neurolysis of the tibial nerve and its branches. The latter includes removal of scar tissue, if any, as well as fascial releases. Problems with a tarsal tunnel release include that the procedure does not address the traction on the structures within the tarsal tunnel (often the primary issue) and that additional scar tissue often reforms in the post-surgical period due to the operative procedure.

There is limited evidence that surgery is effective. One study in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8056802] reported a 38% incidence of patients “clearly dissatisfied with the result and had no long-term relief of the pain.” Complications were seen in 13% of patients as well, including three wound infections.

Risk factors and prevention

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is known to affect individuals that stand a lot. Strenuous activities involving repetitive eversion, inversion, and plantarflexion at high velocities can produce the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Patients with underlying flatfoot deformities are more likely to have associated tarsal tunnel symptoms.

Obesity is a double risk factor in that weight alone can cause mechanical overload, but it is also associated with diabetes (which causes a neuropathy that may make the nerve less tolerant of even mild compression).

Rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism and gout are thought to be associated with tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Miscellany

The anterior to posterior arrangement of the structures coursing through the tarsal tunnel (namely: the Tibialis posterior tendon, the flexor Digitorum longus tendon, the posterior tibial Artery and Vein, the tibial Nerve, and the flexor Hallucis longus tendon) can be recalled with this mnemonic: “Tom, Dick, And Very Nervous Harry.”

Key terms

Tarsal tunnel, posterior tibial nerve, pes planus, plantar fasciitis, tarsal tunnel release

Skills

Perform a comprehensive history and physical that can identify tarsal tunnel syndrome as well as rival conditions on the differential diagnosis list. Recognize the deformities of the foot and ankle that may place undue traction on the posterior tibial nerve.