25

Wietse Hendriks; Nienke Kamphuis; Ilja Nadorp; Iris Zwart; and Esmee van der Steen

Defining Hearing Impairments

Hearing loss is a rising global concern with regards to public health. However, this is not a commonly known subject to many people, most likely because it is a non-life threatening, invisible disability (Chadha, Cieza & Krug, 2018).

Definition

Some causes of of hearing impairments include ear infections, ototoxic medicines, and exposure to loud noises (Chadha, Cieza & Krug, 2018), consequently some form of hearing impairment is more common than we think.

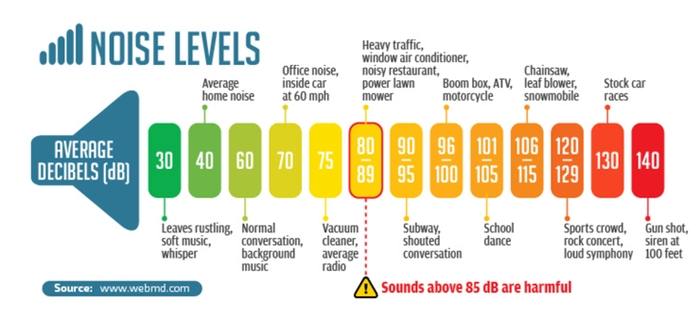

To understand what a child can hear, doctors determine the volume at which they can hear sounds. This is measured in decibels (dB).

A child is seen as hard of hearing when they have difficulty with hearing sounds between 35 dB and 90 dB. A regular conversation can be heard at 60 dB. A hearing loss of over 90 dB means that the child has profound hearing loss,, commonly known as deafness (Fenac, 2017). They have little to no hearing at all. Currently, there are multiple ways in which children who experience hard of hearing can be helped by technology to hear more than what they can without these aids, such as hearing aids and cochlear implants.

Quality of Life and Theory of Mind

Individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals expectations, standards and concerns.

(World Health Organization, 2016, as cited from Roland, Fischer, Tran, Rachakonda, Kallogjeri, and Lieu, 2016).

The quality of life for children is dependent on the parents/caregivers and the child’s environment as well as on the child itself. There are deaf children who are born into families with hearing parents and children with deaf parents. In some countries, such as the United States, 90-95% of deaf children are born into hearing families (Goico, 2019). Several studies assert that these children can lag behind in development compared to hearing children of hearing parents (Woolfe, Want & Siegal, 2002).

Children with at least one parent who is deaf or hard of hearing are often raised using a form of sign language and are therefore able to communicate with others and express themselves. These ‘native signers’ (Woolfe, Want & Siegal, 2002), demonstrate development benchmarks similar to hearing children (Schick, Villiers, Villiers & Hoffmeister, 2017). In addition, children who are deaf or hard of hearing often create their own sign language, or ‘homesigns’. These children benefit from meeting other peers or adults who have hearing impairments in schools or in their community (Goico, 2019).

One aspect of quality of life is feeling connected to others. This connection relates to our perception of our own position and our understanding of others. Our understanding of others connects to the psychological concept of the ‘theory of mind.’

Empathy and understanding are key aspects of theory of mind and from age 4, most children have developed this ability/skill. Assessing theory of mind in children with hearing impairments who grow up in families with hearing parents and in hearing-centered communities is challenging because theory of mind is largely dependent on language acquisition.

There is an ongoing debate between researchers who argue that deaf and hearing children are empathetic and others who assert that children with hearing impairments lack the levels of empathy of their peers (Peterson, 2016). This is important because views of child development influence the types of education recommended for children with hearing impairments.

Age and Hearing Development

Unilateral (one ear) or bilateral (both ears) hearing loss can occur at all ages (Healthy Hearing, 2020). In the United States, newborns are usually screened for hearing problems shortly after birth (ASHA, n.d.) to determine whether the child suffers from congenital hearing loss. Other non-genetic reasons may be caused by complications during birth, premature birth, use of drugs and alcohol during the pregnancy by the mother, brain disorders, or infections suffered by the mother.

Infants or young children should show clear signs of development, such as startling at loud sounds before the age of three months, be able to move their eyes in the direction of sounds between four and six months, and understand common words sometime between the ages of 7 – 12 months (Roberts and Hampton, 2018). It’s important to keep in mind that, “Children develop at their own rate. Your child might not have all skills until the end of the age range.” (ASHA, n.d., Birth to One Year).

When children reach the age when they enroll in schools, hearing issues may become more prominently problematic than when still an infant. Although the quality of life of children with hearing loss in both their ‘social and school life’ and ‘emotional and physical functioning’ is similar to children with normal hearing (van der Straaten, 2020), depending on the severity of the hearing loss, academics may be affected. A study carried out by Tomblin et al (2020) amongst students of varying ages within primary schools found that students with mild and moderate hearing loss perform well academically..

Concerning physical challenges, children with unilateral hearing may develop spatial hearing issues, resulting in the inability to accurately localize the source of a sound (van Wieringen, Boudewyns, Sangen, Wouters & Desloovere 2019). The result of this can cause dangerous situations, for example in traffic or emergencies. Children with hearing loss show more changes in static and dynamic balance when grouped by age, although improvement does show throughout their lives (7-18 years old). Any intervention to improve their balance, it is stated, “should be conducted not only in childhood but also in adolescence, and this may be incorporated into the school environment” (Melo et al, 2017, p. 266).

In adolescence, students with hearing loss have shown emotional and behavioural issues (Hatamizadeh, Adibsereshki, Kazemnejad, and Sajedi, 2020). This age range usually, according to the previously mentioned research, struggles with emotional issues, caused by stress caused by various events taking place, such as school transition. It is stated (p. 2), however, that “The emotional abilities of individuals with hearing loss are influenced by their unique developmental path, and they usually experience more socio-emotional risks than their hearing peers”. The impact on the socio-emotional issues depends on many factors, however, they may be influenced by the severity of the hearing loss, strategies used in the home situation and early intervention. The research by Hatamizadeh et al (2020) uses resilience training as a solution and concludes that “resilience training program was very effective at improving emotional intelligence and could be readily used to help students with hearing loss improve their emotional abilities” (p. 1).

Theory of Mind is, "the ability to understand that other people have mental states (thoughts, desires and beliefs) that may be different from ones own.” (Woolfe, Want, and Siegal, 2002, p. 768)