59

The Importance of Resources

It has been proven that the group of students who received the mental health promotion and prevention program in schools are less likely to have a hard time dealing with their own mental health (Franklin, Kim, Ryan, Kelly, & Montgomery, 2012). Furthermore, childhood is an important developmental period for future mental well-being. People who built a high level of self-confidence by receiving those kinds of mental health education in early years have a long-term effect on their life. They are less inclined to have depression between ages twenty-six to thirty-one in comparison to who did not receive such education (OECD, 2015).

Research has identified two interventions in school-based mental health initiatives which can be used alongside each other. These are programs enhancing mental health and well-being through working on social and emotional competencies and resilience skills, and schemes that prevent mental health difficulties, behavioural issues, and at-risk behaviours (Weare, 2010). Canadian Mental Health Associate Ontario resonates with those views. They strongly believe in the importance of mental health education in schools (2020). Here are suggestions made by the association (Canadian Mental Health Associate Ontario, 2020, para. 4):

- Promoting active living (health and physical education classes, sports teams and intramural activities)

- Teaching children and youth about healthy eating

- Providing healthy eating options

- Teaching coping skills, such as self-awareness and stress management

- Promoting positive self-esteem

- Creating an open environment for talking about their problems and questions

- Providing spaces for relaxation, such as a lounge and quiet corners within classrooms

- Displaying relevant materials for children, youth and families

- Implementing and actively supporting policies for safe and accepting schools, including bullying prevention and intervention policies

Some of those suggested mental well-being promotions are covered by mandatory curricular activities worldwide. For instance, active living and healthy eating are discussed in physical education or biology classes. Contrarily, there are fewer common subjects that teach how to build self-awareness, stress management, confidence, positive self-esteem, self-efficacy, autonomy, etc. which are often known as personal protective factors against mental illness (OECD, 2015).

Numerous homeroom teachers might think I am not enough to teach mental health because I am not qualified in the area. However, interestingly a study from Hong Kong, China found that improvements from a mental health programme led by teachers was better than professionally led sessions, since teachers have already established positive relationships with their students (Lai et al., 2016, as cited in Choi, 2018). With helpful resources, students can benefit from mental health learning with their homeroom teachers.

Discuss or write

- Rate and describe your past experiences of mental health education in your school(s).

- How confident are you in teaching about mental health in your future class?

Helpful Resources

Internet based:

Young Minds is a website from the UK’s leading charity for children and young people’s mental health. Their mission is to stop young people’s mental health from reaching a crisis point (Young Minds, n.d.). They value everyone’s voice, optimism even for an ordinal event, kindness, and integrity. The website provides various contents, training courses to mental health education resources, and even mental health literature. There are different types of school resources available: video, activity, lesson plan, tips, and poster. It gives teachers the opportunity to choose a topic and age groups.

Mentally Healthy Schools is a website that promotes mental health education for primary school. It was started in 2018 by the Duchess of Cambridge as a legacy of the Heads Together campaign. They strongly believe in the importance of early intervention. This website covers: teaching resources, risks and protective factors, mental health needs, and whole-class approach. Almost all of the resources are free and revised by experts and they are:

- clear, accurate and convey a positive message about mental health

- age and key stage appropriate

- clinically safe

- evidence-informed or based on early intervention foundation oriented

- suitable for all children

- up to date (Mentally Healthy Schools, 2020, para. 11).

In comparison to Young Minds, Mentally Healthy Schools provides more resources than professional face to face and online courses.You can check out their YouTube channel to learn more.

Children’s mental health week by Place 2 Be is a charitable organization that shares mental health education for young people since 1994. As of 2015, they have started mental health week every year. It aims to spread awareness for the importance of children’s mental health. The website provides downloadable material for the week and easily implement them in your classrooms.

Here are the themes and short activities which were covered in the past four years:

| Theme | URL |

| Kindness | https://www.place2be.org.uk/media/1xokfmjx/spread-a-little-kindness-activities-for-schools.pdf |

| What makes us special and unique | https://www.place2be.org.uk/media/jl2fz30y/being-ourselves-activities-for-schools.pdf |

| Connection physical and mental health

|

https://www.place2be.org.uk/media/qgje55xe/healthy-inside-and-out-activities-for-schools.pdf |

| Bravery | https://www.place2be.org.uk/media/ti4fo3rk/find-your-brave-activities-for-schools.pdf |

| Express yourself | https://www.childrensmentalhealthweek.org.uk/about-the-week/ |

Literature:

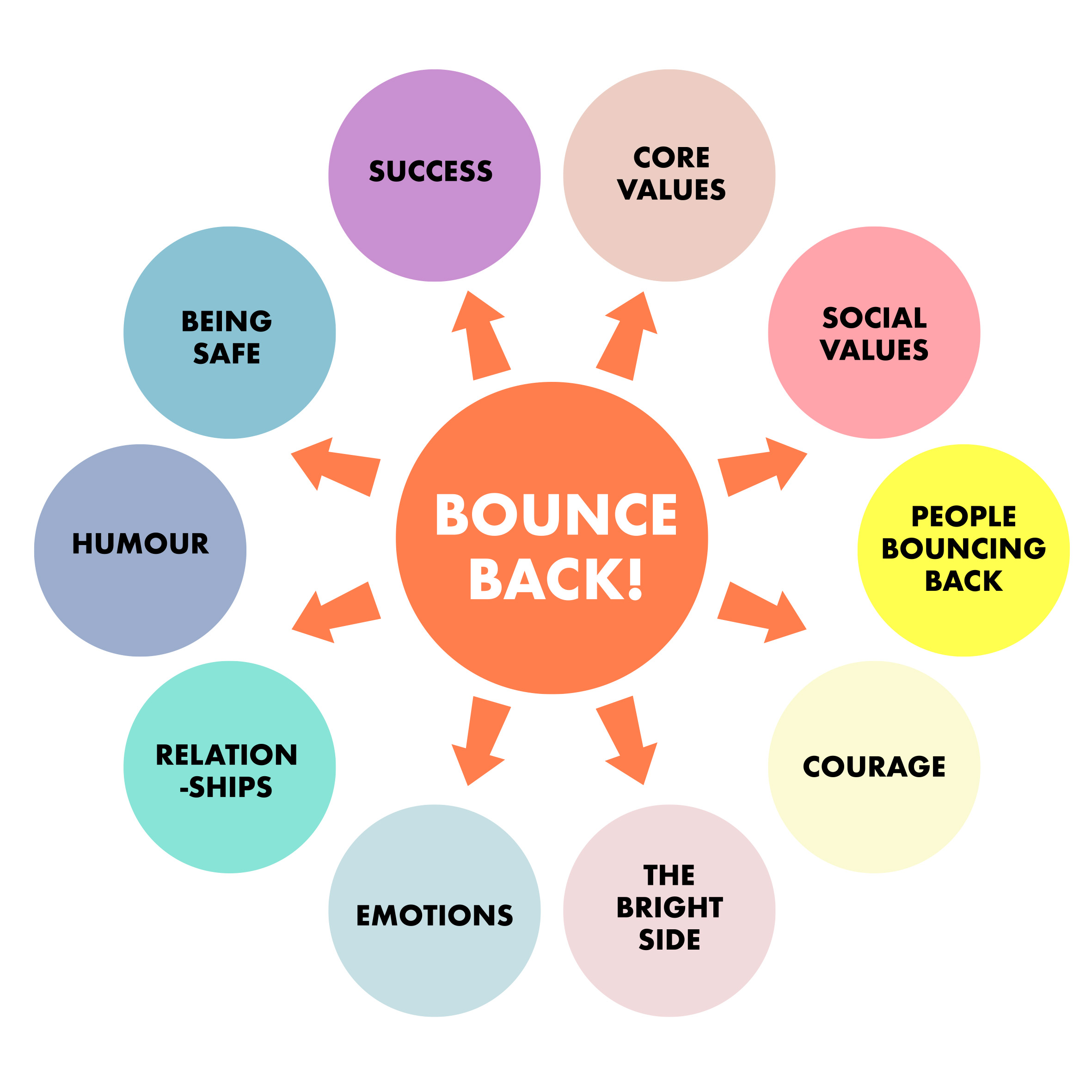

Bounce Back is a programme from Australia. It promotes social emotional skills, resilience, and a safe supportive school environment. Bounce Back is supported by well-known Australian educators, psychologists, and best-selling authors. There are three different levels: and each book contains an up-to-date handbook which is based on the evidence from the most recent research, and a variety of ten units:

Each unit includes children’s literature, thinking tools, and cooperative learning tools. Furthermore, it contains a variety of cross curricular classroom activities:

- develop positive and pro-social values, including those related to ethical and intercultural understanding

- develop self-awareness, social awareness and social skills

- develop self-management strategies for coping and bouncing back

- find courage in everyday life as well as in difficult circumstances

- think optimistically and look on the bright side

- boost positive emotions and manage negative emotions

- develop skills for countering bullying

- use humour as a coping tool

- develop strengths, skills and attitudes for being successful (Pearson, n.d., para. 3).

Self-learning for students:

You’re a Star (and other books for children by Poppy O’Neill

These books deliver the practical guide with proven cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness methods used by child psychologists in schools with a variety of simple activities to encourage child: to grow their self-esteem (O’Neill, 2018), to overcome anxiety (O’Neill, 2019), to build on their self-belief (O’Neill, 2020), and to improve their self-confidence (O’Neill, 2020). It is targeted at primary school children aged around seven to eleven, or eight to twelve because by learning those kinds of protective factors against mental illness will have a positive impact on their future lives. Each book has its own friendly character that supports along the fun activities sheets and simple reading.

These books can be used for children’s self-study as well as classroom activities.

An example activity to try out and to understand the concept from You’re a star (O’Neill, 2018):

ACTIVITY: WHAT MAKES ME GREAT!

Even if you’re feeling down, you’re still special and unique, and activity invites you to give yourself a high-five for being so awesome. In each of the bubbles below, write down or draw something that you’re good at or like about yourself (O’Neill, 2018, p. 18):

The discussion on mental health in primary schools in this chapter aimed to create awareness among teachers about the importance of mental health education especially for young learners. Being empowered with knowledge about the common mental health illnesses and how they manifest in the classroom is the first step. Sensitivity about misconceptions and how different cultural or gender perspectives about mental health might add to the complexity, is an additional element to equip teachers. It is imperative for teachers to have confidence on how to talk about the topic of mental wellbeing in the primary classroom.

There is a growing need for young people to build and developmental resilience to cope with challenges and hardships in everyday life. According to the World Health Organisation (2018), data shows by promoting and protecting children’s health, both in the short term and in the long run, it expects to bring a positive contribution to the economies and societies. Learning how to talk about mental health is important, as prevention begins with a better understanding. Better understanding refers to understanding the warning signs, and symptoms of mental illness. Misinformation about mental illness can cause anxiety, strengthen stereotypes, and lead to stigma (AACAP, 2017). Parents, teachers, and the greater community can help build life skills in dealing with the everyday challenges that can affect mental health.

How to talk to individual students

The conversation used to approach sensitive topics such as mental health should be a natural interaction. It is important to note that the responsibility does not solely fall onto the teacher, but also on the principal, school nurse, parents, and others. Significant adult can play a larger role in supporting the individual needs of a child, depending on the severity of issues children might face.

Lower primary:

Before starting a dialogue with a student, it is important to know the warning signs for mental health problems. Knowledge can be the first step in helping a child. It is important to note that emotions are not the only way to show signs of mental illness. When young children learn more about what emotions can be experienced, it is more likely that a child will seek help when needed. An understanding of emotions will provide children with the tools necessary to address issues independently. Furthermore, children will be more likely to show understanding towards peers who might express challenges of mental health as a result of their ability to empathise (TCI, 2020).

When having an emotional discussion there are a few strategies one can use to help the child talk about the issues experienced. This can be done by allowing the child to draw, model, or play with toys while the conversation is progressing. This can be a very helpful tool to give the child some space during any discussion regarding mental health.

It is important to distinguish between feeling a bit down and a more serious underlying problem (Freud, 2020).

Below are some examples of ways a conversation can be initiated. These examples are taken from the National Centre for Children and Families (Freud, 2020).

- You don’t seem your usual self today. Would you like to talk about anything?

- You look sad/worried today. Do you want to have a chat about it/is there anything I can do to help?

- You said something interesting in circle time about how you felt when… How do you feel about it now?

Using the right language can be difficult, here are more examples of phrases and questions used to start a discussion.

Discussion Point:

- What are some ways you would talk to encourage a student to open-up?

- Would you use other questions to start a discussion?

Upper primary:

In upper primary, educators have a better opportunity to build more in-depth relationships with students concerning the topic of mental health. At this time more critical one on one discussions can be held. For educators, one method for effective communication for the upper primary is the use of a conversational tool called: Motivational interviewing (MI). This technique helps individuals reflect constructively on personal behaviours, then deciding for themselves what they want to change and how they will go about making changes. This method was originally developed by experts at the University of New Mexico, the points below are a summary of how the tool works (Classroom Mental health et al., 2020).

There are 2 steps used in MI, firstly build motivation for change, secondly, strengthen the commitment to change. The first step: build motivation for change, is using the following acronym: OARS (Open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summarisation).

- Open-ended: Use prompters such as “Tell me more” or “Is there anything else?” to ask about feelings, ideas, concerns, and/or plans.

- Affirmations: Reinforce and complement – acknowledge the positive to build responsibility and self-esteem.

- Reflective listening: Repeat back, in your own words, what you think the student is telling you.

- Summarisation: Toward the end of the conversation, to make sure you and the student are working on the same things. Remember to include the positive along with the negative.

Secondly, we look at strengthening the commitment to change.

This only starts once a student has stated they desire change, following up could be:

- Using a few more open-ended questions for example: “What are some of the reasons you think now is the time to make a change?”

- Discussing elicit suggestions to make a plan with the student on how to deal with their current situation.

- Evaluating the positives and negatives of taking actions and inactions.

For more information on this conversation technique, explore the following site for more real examples of sentences to use in discussions (Classroom Mental health et al., 2020).

Discussion Point:

Classroom involvement

For a teacher, the first and most meaningful step is to have a good relationship with the students. Building this rapport where a child feels safe and can trust the individuals in their environment can be done through the language used. This is noteworthy, as children learn best when they feel accepted, enjoy a positive relationship with their peers and teachers, and lastly, when children are active, visible members in a learning community (Ministry of Education, 2015).

Lower primary:

It may be challenging for educators to start the conversation about mental health in the primary classroom. It is, however, increasingly important to make conversations surrounding the topic of mental health a regular part of classroom discussions. If done often, it will allow a child to feel increasingly comfortable with the topic of mental health (Freud, 2020). One of the methods that could be used in the classroom is a mood board or mind map for emotions felt such as; feeling good, feeling bad, uncertainty, insecurity, fear, and shame. This is a way in which prior knowledge of understanding of emotions is assessed. For example, asking a child “Do you understand each of these emotions?” and then partaking in further discussion to see if the child can discuss and or express some emotions.Therefore, a discussion can lead an educator towards where knowledge is lacking and where more vocabulary is needed to describe how an individual might feel (Cache, 2018). Classroom discussion can go further.

For example, this activity and resource (and others) from Teaching Tolerance provide lesson plans for discussing this topic in the classroom:

Discussion Point:

- To what extent is it an educator’s responsibility to ensure and create a safe learning environment?

- To what extent is it the schools communities’ responsibility to ensure and create a safe learning environment?

Upper primary:

If mental health is a discussion that happens regularly in a classroom, it could be important to explore what the children think about self-care, what it is, what it looks like, and lastly, what it is not.

It might be valid for teachers to explain the difference between mental health and mental illness. It is important to make these discussions age-appropriate, therefore be careful in the way these topics are approached (TCI, 2020). A teacher might start a conversation by stating that most children feel anxious at some point and asking the students when they think it should be explored further.

It could be very helpful to describe symptoms of anxiety, or the symptoms of a panic attack. A child might not understand the feelings when it arises. Lastly, allow children the opportunity to ask questions, if anything was not explained properly allow a chance to explain more in-depth (TCI, 2020).

When discussing mental health, pay attention to how the child reacts to knowledge being shared, it can help with creating a better connection. Open questions can encourage critical thinking, it provides a space for children to give opinions on important matters. When discussing different perspectives, ensure and encourage all to be respectful to one another. As a teacher, this opportunity can be used to expand the emotional vocabulary of children (Freud, 2020).

For more resources to explore how to talk or teach about this topic, Teaching Tolerance provides lesson plans for discussing this topic of illnesses and health in the classroom. Here are some examples of activities that can be adapted and modified to suit the topic of mental health and mental illness.

| Activity | URL |

| In this lesson, students will explore the ways people with a critical health condition or disease might feel, as well as various ways they can support and show compassion toward those who are living with an illness (Teaching Tolerance, n.d.). | https://www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/tolerance-lessons/showing-compassion |

| The focus of this lesson is on accepting others as well as ourselves, and on being the best that we can be—which includes maintaining our health and encouraging those around us to do the same(Teaching Tolerance, n.d.). | https://www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/tolerance-lessons/healthy-bodies-healthy-body-image |

Community involvement

Conversations surrounding the topic of mental health will only be successful if the community itself is supportive of the idea. This can however only happen if all staff are alert, watchful, and curious surrounding all children’s behaviour at the school. Educators should be encouraged to spot out behaviours that the children known would not usually do. This can be done by, for example: observing body language, their interaction with other pupils, what they say, what they draw, and what they do in school (Freud, 2020). Several countries have mental health policies in place that support children’s mental health development.

If the school community has an ethos that has constructive, caring relationships built on trust, safety, kindness, and security a safe learning space will follow (Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand, 2009). Creating a safe environment to respond to stress, change, and lastly, critically looking at the way mental health is viewed in the community. Schools could for example focus on raising more awareness of bullies as bullying can affect children into adulthood with increases in the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and self-harm (Fazel et al., 2014). The guidelines stated in the New Zealand curriculum gives an idea of policies that could be developed to support the development and understanding of mental health. The New Zealand curriculum states.

Through their learning experiences, students will develop their ability to (NZC,2009,P10):

- express their own values

- explore, with empathy, the values of others

- critically analyse values and actions based on them

- make ethical decisions and act on them (Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand, 2009).

It is important that educators create a safe environment for children as this gives an environment where children are more likely to learn even more. For example, The New Zealand curriculum also states: “Evidence tells us that students learn best when teachers: create a supportive learning environment (NZC,2009 p34).” A school might complete a school climate scale, this is a means of measuring students’ or teachers’ perception of how the environment of classrooms and schools as a whole affect education. Once completed it could aid in the process of selecting a universal intervention of school-wide character development. Educators or school administrators might use a screening program to identify children at risk of suicide, programs can help in providing support earlier (Fazel et al., 2014).

Having explored different approaches of how to talk about mental health to primary school children, the next section will introduce the concept of mindfulness, a specific skill that children may learn and apply to improve their own mental well being in the classroom.

Mindfulness as a strategy to address mental health challenges in the primary classroom

Mindfulness is defined as the process whereby someone purposefully focusses on being aware of themselves in the present moment with a positive attitude that refrains from judging (BC Hospital, 2019). It is a technique that is successful in addressing stressful situations and it promotes emotional well-being. Mindfulness techniques are varied, flexible and can normally be practiced anywhere and can even become a part of a regular daily routine. It typically involves techniques associated with meditation or breathing (Kelty Mental Health Resource Centre, n.d.). According to Wedge (2018) the concept of mindfulness became known in 1979 when it was introduced at the medical centre of the University of Massachusetts to assist patients in dealing with stress and pain. She continues to say that the concept is in reality more than 25 centuries old as it dates back to the ancient teachings of the Buddha to promote happiness and healing. In the Buddhist philosophy, this technique of focusing on the present without analysing or thinking is referred to as “lucid awareness”.

Why have mindfulness-based interventions become so popular?

Mindfulness based interventions have become increasingly popular as a technique to be applied in schools as it is a method that is relatively cost effective while several emerging case studies seem to indicate that both teachers and children respond positively to it (Dunning et al, 2018). However, it seems that the enthusiastic support for mindfulness has moved ahead without the development of a strong evidence base backed by solid research involving children.

According to a 2010 study in Melbourne, Australia, previous recommendations about the value of mindfulness meditation is based mainly on research done on adult clinical trials while insufficient data exists on trials involving children in the classroom (Joyce, Etty-Leal, Zazryn and Hamiltion, 2010). Therefore, this study in 2010 focused specifically on primary school children at two primary schools over a ten-week period. Even though it was limited in sample size and without long-term follow-up or a control group, the schools did find that it was fairly easy for the children to learn and apply the mindful techniques and that it had a positive effect on dealing with anxiety. A criticism of this study is that the positive results may simply be the result of the teachers having spent more time with the children and potentially not directly as a result of the mindfulness-based interventions.

In a further study published in 2012, Weare confirms that although research results on the impact of using mindfulness techniques for children are still limited, work in the field is increasing at a rapid pace. Weare (2012) has established several conclusions based on a systematic review of two studies published in reputable scientific journals including peer reviews. The conclusions are that children enjoy these techniques which they embrace easily, that it does reduce their levels of anxiety or stress that could manifest in negative behaviours, and that it assists them in their ability to focus, pay attention and therefore effectively use their executive functions such as planning, reasoning and solving problems.

Continued research is cited by Azarian (2016) whereby a study in 2015 of children in grade four and five who participated in a four-month meditation program found that they had improved their ability to apply their executive functions in areas such as working memory and cognitive flexibility. Of special interest is a study focusing on developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience (Lyons & Delange, 2016), which found that meditation can influence cognition the most during the early stage of brain development as prefrontal connections are made at its fastest rate during childhood. This brain plasticity in young children implies the strong potential impact of meditation on executive functions in children.

Perhaps the most significant contribution of research on the benefits of mindfulness for children is found in the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials conducted up to October 2017 (Dunning et al, 2018). This research started with an analysis of 1409 studies. Through a process of elimination, the results are based on only thirty-three independent studies and 3666 children. In considering only those trials that involved active control groups, they found significant benefits of mindfulness-based interventions in relation to increased wellbeing and reduced depression, anxiety and stress. Considering the above research findings that have clearly evolved over time, it can be concluded that there is sufficient evidence that empowering children with the skills to practice mindfulness could indeed assist them in improved mental wellbeing.

Reflection and discussion:

Why do you think that mindfulness-based interventions have become so popular despite the lack of research-based evidence concerning children?

How can we teach primary school children about how their brains work?

One of the interesting methods that are used to teach children about mindfulness is to teach them about how their brains function, how they can deal with unhelpful thoughts and how to react when they feel scared or angry. According to Lightfoot (2019), children no longer learn only about their bodies for example, through the song that refers to head, shoulders, knees and toes, but they also begin to learn about parts of their brains such as amygdala, hippocampus and pre-frontal cortex. Bergstrom (2016) details how to explain to children how mindfulness and the brain works. It starts with the fact that the amygdala creates an emotional response to block anything that seems threatening by creating a fight, flight or freeze reaction. The problem is that the amygdala does not see the difference between perceived and real dangers. An example could be to freeze when having to write a test or make a speech in front of the class. Due to this blocking reaction, the information does not reach the prefrontal cortex which is the part of the brain that analyses information and that allow for logical reactions. Furthermore, the emotional stress reaction does not allow the brain to access the hippocampus which can be described as the librarian of the brain where all the memories are stored.

This is the part that will remind the child that they do have skills to deal with the threat for example, they have successfully passed many tests before or have been able to do a speech in front of the class. Bergstrom continues to explain that mindfulness is the process that the children can use to calm the jumpy amygdala down and therefore enables the calm prefrontal cortex to help them make good choices. This process is demonstrated in Figure 1, which is helpful as a visual representation that explains how to obtain a balanced response.

Figure 2: Bergstrom, C. (2016, March 15). Mindfulness and the Brain – How to explain it to Children.

Reflect and Discuss:

Do you think that teaching children about how their brain works could be helpful in improving their emotional well being? If so, how?

Mindfulness-based learning activities for primary school

In the following section a series of mindfulness-based learning activities are proposed from which teachers may select relevant activities for their classroom needs.

Amy, Tex and Hippo – my three friends: Building on the approach that children can learn about the value of mindfulness by learning about their brains, Bergstrom (2017) acknowledges that words like amygdala, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus may be too complex for primary school children. He therefore invented the playful characters named Amy, Tex and Hippo that the children can get to know as shown in Figure 2. On the website Blissfull Kids: Mindfulness made playful and sustainable (Bergstrom, 2017), detailed character descriptions, examples as well as a storyline to introduce the characters and their roles are available.

Read this story and lead a discussion around the following:

- Who is your favourite character? Why?

- What is their favourite sentence to remind you of their job in your brain? Like a catch phrase?

STOP Meditation, focusing on senses: Dr Vo from BC Children’s Hospital (2019) proposes the following STOP Meditation technique for children, as it is and effective way whereby children could become aware of themselves in the moment:

- Stop what you are busy with

- Take three deep breaths

- Observe what is happening in the moment without thinking

- Proceed and go back with what you were doing but stay in the present moment

To develop the “observe” step further, the focus should be on three senses by asking the following questions while breathing slowly:

- What are three things I can hear right now?

- What are three things I can see?

- What are three things I can feel?

I can do hard things: Read aloud video (KidTimeStoryTime, 2019) of book: ‘I can do hard things: Mindful Affirmations for Kids’ by Gabi Garcia (2018), which introduces children to a variety of positive affirmations that they can discover if they listen to the quiet voice inside them with attention and let this voice be their guide.

Lead a discussion around these questions to enable children to become aware of their own potential still quiet places:

- Which affirmation statements did you hear in the book?

- What do you think the author means when she refers to: that quiet voice inside?

The Mindfulness Jar: Play the video of the “Mindfulness Jar” (Awad, 2015) and read the following text while the video plays: “The glitter is your thoughts when you are upset. They are all over the place and make it difficult to think clearly. As you watch, notice how the glitter settles after a while. The same will happen to your emotions if you are able to go to a calm quiet place in your thoughts and things will become clearer.”

A Still Quiet Place: (Gozenonline, 2012) invites the children to draw a picture of a still quiet place and then closing their eyes and visiting this place in their minds, all the time concentrating on slowly breathing in and out.

Lead a discussion around these questions:

- Which ideas did you see in the video that can help you go to a still quiet place?

- Which ideas do you think you might use?

Listening to my body: Play the video of the online book: “Listening to my body” (HungryWolf Reads, 2018) which helps children to discover the sensations in their bodies and the link between sensations and feelings.

Lead a discussion around the following questions to help children become aware of the sensations in their bodies and how it links to their feelings:

- What are sensations?

- Which sensations did we hear about in the story?

- Which feelings do we have when our needs are taken care of?

- Which feelings do we have when our needs are not taken care of?

- Which needs do we all have?

- What can we do when our needs are not taken care of?

Additional mindfulness-based resources

| Resource | URL |

| Body Scan Meditation by Gozen (2016), where children are encouraged to scan each part of their bodies by sliding from one to another, releasing the tension in each part until they have covered their full body. | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIC-Io441v4 |

| Mindful Eating Chocolate by GoStrengthsOnline (2012) inviting the children to re-discover chocolate by feeling, smelling and tasting it, very slowly | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guXTS1YFf-0 |

| Breathr App: BC Children’s Hospital (2019) which offers a variety of mindfulness techniques and further interesting facts about the brain and how it supports mindfulness, explaining that it is easy, flexible and fun to try. | http://www.bcchildrens.ca/about/news-stories/stories/how-mindfulness-can-help-kids-look-after-their-mental-health |

| Mindfulness for teachers: Video that explains the concept of mindfulness targeting young adults, which could be useful for student teachers as they continue with their studies and start their careers as teachers (KeltyMentalHealth, 2016). | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9kC9mFfQyE&feature=emb_logo |

Think and discuss:

Which of the listed resources would you consider testing in the primary school classroom? Why?

The discussion on mental health in primary schools in this chapter aimed to create awareness among teachers about the importance of mental health education especially for young learners. Being empowered with knowledge about the common mental health illnesses and how they manifest in the classroom is the first step. Sensitivity about misconceptions and how different cultural or gender perspectives about mental health add to the complexity, is an additional element to equip teachers. It is imperative for teachers to have confidence on how to talk about the topic of mental wellbeing in the primary classroom. This chapter develops the concept of mindfulness and how teachers may use it to teach primary school children how to deal with mental health challenges. Furthermore, it offers a range of learning activities and practical resources to choose from, thereby empowering teachers with the skills necessary to develop a positive and confident mindset about handling mental wellbeing in their classrooms. The ultimate aim of this chapter was to motivate teachers to find the appropriate resources that suit their individual teaching styles in order to equip their young students with the skills needed so that they themselves can improve their own emotional wellbeing.