Tiffany Buckingham Barney

A rhetorical analysis is somewhat like a critique written by a food critic. Not the casual critic who says things as deep and meaningful as “That was super yummy this time.” No. Something more sophisticated―more along the lines of Anton Ego, the seemingly sesquipedalian rhetorician of cuisine.

Okay, maybe not necessarily as fancy and piercing as one would picture the fictional critic who can shut down entire restaurants with one review, but definitely one who is educated enough in culinary art to take the time to account for their enjoyment, appreciation, and understanding of the food―or rather, the enjoyment, appreciation, and understanding that the chef elicits in the audience: the eater.

A food critic wouldn’t discuss whether the meal is right or wrong, but whether or not the preparation and presentation of the meal were appealing to the guests, delicious to eat, and satisfying. Was the turkey prepared successfully by using a barbecuer or deep fryer or smoker or oven? How did that affect the flavor? How did the meal taste? Was it delivered in a timely manner in a location that worked well? Did it supply the nourishment and satisfaction the host was trying to provide and that the audience, the eater, expected?

Likewise, a rhetorical analysis is not about whether the topic itself is right or wrong, but about how successfully the author of a piece delivered the topic. How well did the author use rhetorical devices ⇛ to elicit rhetorical appeals ⇛ to deliver a rhetorical argument? This process is explained more in another Pressbooks article written by yours truly titled “Unpacking the Process of Rhetoric.” A rhetorical analysis analyzes the rhetorical choices and success of another author’s work. Essentially, was the way the piece was written effectual in convincing the reader?

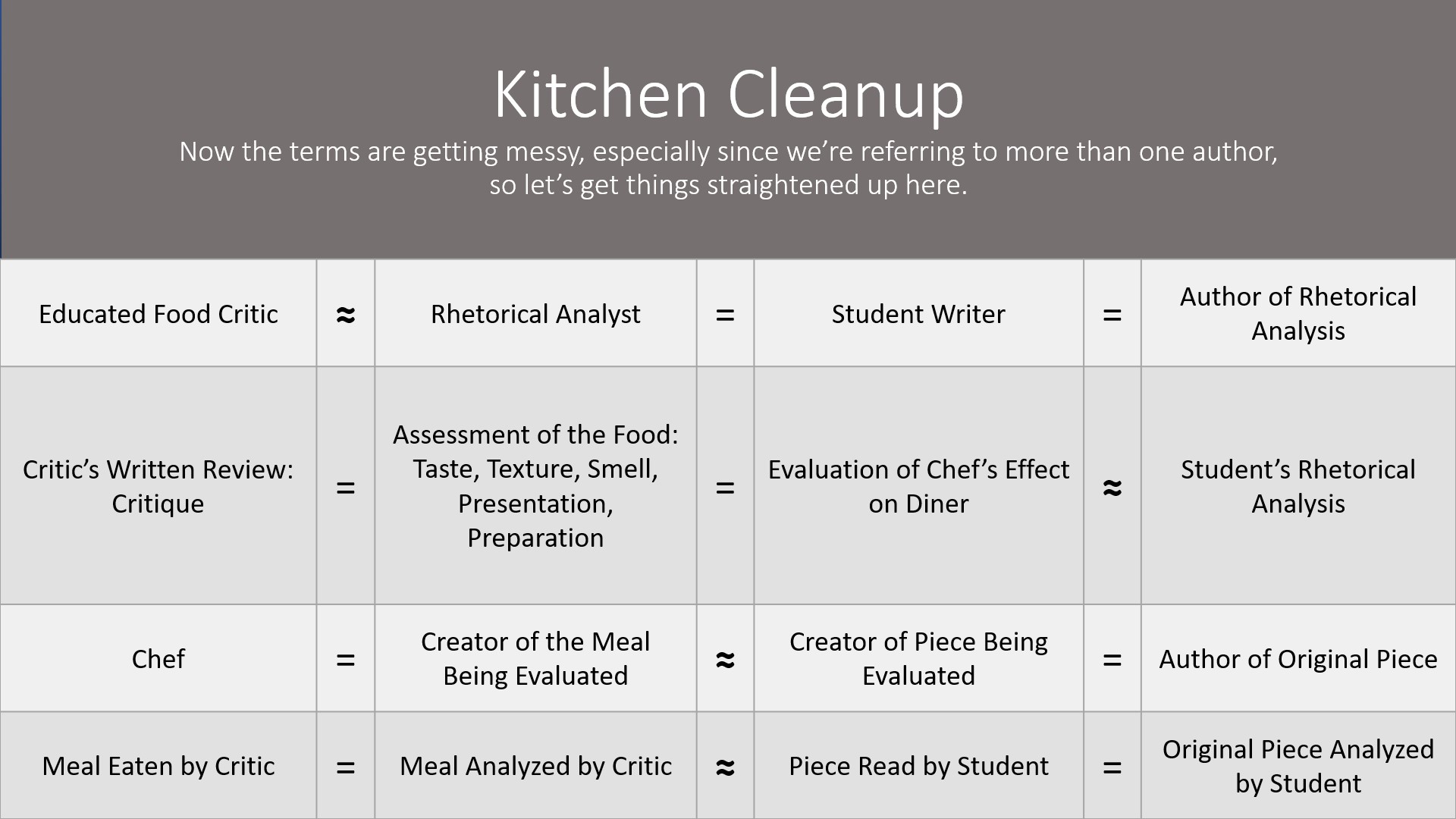

THE STUDENT WRITER AS FOOD CRITIC

Much like the casual food critic who comments on the yumminess of the food, an analysis can be given by anyone and is sometimes referred to as a review or an evaluation. A rhetorical analysis, however, is written by an evaluator of the rhetoric, in this case the student writer, who assesses the author’s effective use of rhetorical devices ⇛ to elicit rhetorical appeals ⇛ to deliver a rhetorical argument. (See what I did there? Repetition is a rhetorical device.)

An educated food critic can taste the oregano, identify whether something is pan fried or deep fried, notice the pairing and the presentation of the dish, and can comment on how those choices changed the outcome of the meal; a rhetorical analyst can identify the emotion evoked (pathos), the mastery displayed (ethos), the reasoning presented (logos), and the way in which the writing evokes those appeals and uses them to deliver the argument.

So, the rhetorical analyst or student writer will, essentially, give an argument about the way the author presented the (rhetorical) argument and (rhetorically) appealed to the audience.

A RECIPE FOR RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

The questions then arise of how does one evaluate the way an author persuaded the audience using rhetoric? What tools and ingredients ought to be considered?

A food critic who is educated in culinary craft carefully consumes a meal, taking note of why the food was made and for whom with an exploration of the ingredients and the methods used to create the meal while analyzing the smells, the flavor, the texture, and the presentation of the food and judging its overall triumph (or not) in the eater’s mouth.

A rhetorical analyst carefully reads a piece, taking note of the purpose and audience with an exploration of the rhetorical devices used to create the piece while analyzing the rhetorical appeal to the audience and judging its overall success in the audience’s thoughts.

Rhetorical Staples

Staples in a kitchen are basic ingredients that cooks always have in stock because they store well and are used in a lot of recipes. Things like flour, sugar, rice, and beans can be the basis for many recipes, even if the eater is the chef or is only imagined. (What? Keep reading …)

Rhetorical staples are the elements in every piece of writing. All writing is done for a purpose and all writing has an audience, even if the audience is the writer or is only imagined. (Oh … we’re drawing parallels again.)

Purpose

Meals are prepared for different reasons. The purpose of the cooking changes the process and outcome of the cooking. Imagine the difference between the cooking done for a fancy dinner party versus the preparation done for a quick bite before getting back to work. One would likely include a menu and an extensive shopping list with long hours in the kitchen creating an elegant meal for the first, while the latter would likely include a rummage through the pantry or a trip through a drive-thru gathering just enough sustenance to get through the rest of the day.

Pieces are written for different reasons. Indicating the purpose of the piece and sharing that in the rhetorical analysis helps set up the thesis for the analysis. Imagine writing a term paper for an advanced course versus writing a note to a friend. The purpose of the piece changes the way the piece is written, which changes the criteria for the success of the piece. The rhetorical purpose of a piece is part of the rhetorical situation which a colleague of mine, Justin Jory, submits “refers to the circumstances that bring texts into existence.” Jory writes more on other elements to consider in the rhetorical situation in his aptly named piece “The Rhetorical Situation.”

ANALYSIS OF PURPOSE ― Julia Child’s Book Mastering the Art of French Cooking

Audience

Meals are prepared for different audiences (diners). Chefs make different choices of ingredients and preparation methods for different consumers. There are some people who love exotic foods and are interested in trying something different regularly. The challenge then, for a chef, is to wow the eater. Others, usually around five or six years old (and sometimes, boringly, into adulthood), are very limited in their willingness to consume new foods, having their own specific set of staples usually including macaroni and cheese and chicken nuggets.

Writing, likewise, is done for different audiences, thus driving the author to change the content of the writing in order to engage the reader. Imagine writing a letter to the Queen of England versus writing a note to your friend in class. In these cases, it’s not only appropriate to change the register (the variety of language specific to a situation) in which the message is written, but to change the mode as well. After all, texting the Queen of England is probably not that usual for us common-folk. The audience of a piece can be either real or imagined. English classes often use imagined audiences to give writing a specific flavor. Again, my colleague Justin Jory has a cleverly named piece in this Pressbook titled “Audience,” which addresses this idea of actual and imagined audiences.

ANALYSIS OF AUDIENCE ― Andrew Rea’s YouTube Hits Basics with Babish and Binging with Babish

The Meat of the Analysis

The meat (or Beyond Meat for those veggie lovers) is the center entrée and therefore the main focus of the critic’s analysis. After a food critic has taken into consideration the purpose and audience of the meal, major consideration must be given to the individual dishes and the way they were prepared and, of course, the smells, flavors, and feelings incited by the food.

The next most significant part of a rhetorical analysis addresses the rhetorical work the author did, including the rhetorical devices chosen and how those evoke (or don’t evoke) the rhetorical appeals of pathos, ethos, and logos to persuade the audience.

Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices are where it can get nicely messy, thus giving the author of the rhetorical analysis a lot of freedom and choice. Picking out a few of the many rhetorical devices (or strategies or techniques) the author used and acknowledging them (by name or not) gives the evidence needed to further the argument of whether the author appealed to the audience and made the point.

The food critic is aware of the chef’s use of many different ingredients, tools, and methods to create the different comestibles. The critic is familiar with the way in which the chef prepared the dishes, but there is no exhaustive list of these means because there are so many of them. Of course, Wikipedia is attempting such a task with the beginnings of a list of food preparation utensils. (Check it out; have they added an avocado slicer or tofu press yet?)

In a similar fashion, authors use many different rhetorical devices for achieving their goals―so many that a list of all rhetorical devices is difficult to find or create as well. Of course, Wikipedia is additionally attempting to gather all rhetorical devices in one place (see also the Wikipedia entry for stylistic devices), so there’s a start, but there are so many, many different ways to use language to make a point that it’s difficult―even impossible―to identify every way a human could put together language. Because of this, sometimes rhetorical devices are simply described by rhetorical analysts, rather than specifically named.

ANALYSIS OF RHETORICAL DEVICES ― Seinfeld Episode “The Soup Nazi”

Rhetorical Appeals

Discussing the rhetorical devices is coalescent with discussing the rhetorical appeals the author evokes in the audience. How does the author persuade the audience? How does the author appeal to the different parts of the audience’s self?

Along with all the different concepts a food critic considers when writing the piece, the most important is how the food is received by the eater. Smell, flavor, texture, and presentation are intrinsic to the critique. These are crucial to every critique of every type of food regardless of the purpose, audience, ingredients, methods, or tools used. Did the food appeal to each of these important food senses in the consumer? Did the eater enjoy the meal?

Similarly, rhetorical appeals are crucial to every rhetorical analysis. Pathos, ethos, logos, and kairos are intrinsic to the analysis. Did the writing appeal to each of these important modes for persuading the reader? These appeals are crucial to every analysis of rhetorical argument regardless of the purpose, audience, and rhetorical devices used. There is a lot of rhetoric out there about the different appeals, but for a very simple and straightforward explanation of the rhetorical appeals, go to “Ethos, Pathos & Logos: Aristotle’s Modes of Persuasion.” (See what I did there? I used rhetoric to describe rhetoric.)

ANALYSIS OF RHETORICAL APPEALS ― Character Sookie St. James from Gilmore Girls

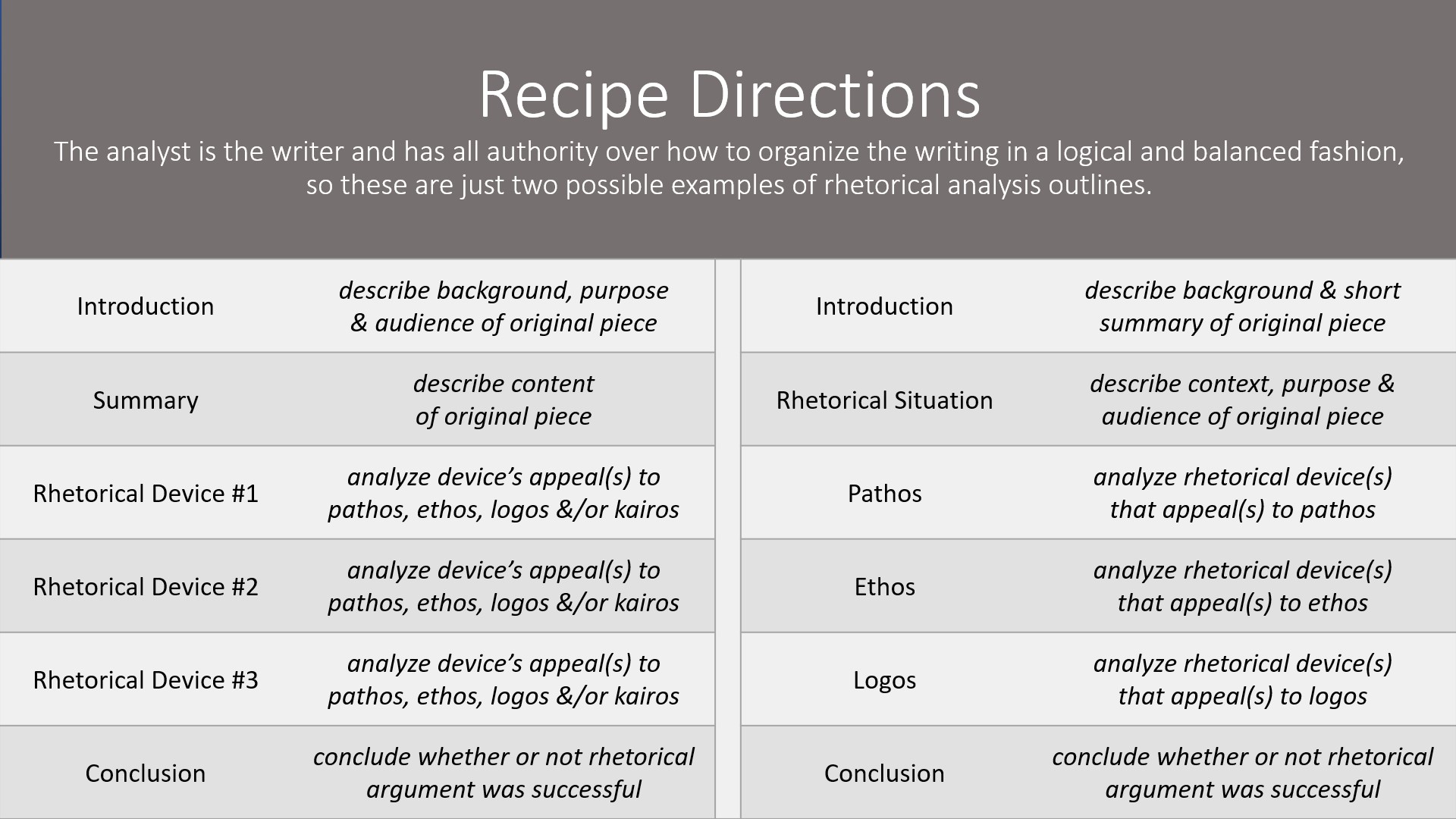

RECIPE DIRECTIONS: THE ORDER OF ANALYSIS

Now, the order of arguments within the analysis does matter, somewhat. A critique of food will usually start by introducing the restaurant, the chef, and the meal. Often information is given about the ambiance of the location and professionalism of the servers. Next is the critique. This part is organized as well, usually going from one dish to another describing the smells, flavors, textures, and presentation of each and analyzing the ingredients and means of preparation along the way.

A rhetorical analysis has a general pattern as well. It usually starts with some context and rhetorical-situation background, and this is followed by a very short summary of the piece being analyzed. None of the meaty portion needs to be done in any particular order; it’s just important to be sure the analysis has some good balance with the size, ordering, and emphasis of each. Rhetorical devices, for example, are better addressed as main points with discussion of appeals within or scattered throughout a set of rhetorical appeals as main points, not mod podged back and forth.

As with most English pieces, a conclusion is customary. Conclusions of a rhetorical analysis are likely to wrap up the argument and reify the answers to the main question of whether the author did the job well of persuading the audience or not.

BON APPÉTIT

A food critic will put all of these pieces together to give the reader of the critique a sense of how the creation and presentation of the food appealed to the eater’s senses and whether the meal was successful or not. Likewise, the rhetorical analyst will identify the purpose and audience of a piece and analyze how the author used rhetorical devices to give rhetorical appeal to that audience and whether the author was successful with the piece to make the rhetorical argument or not.

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS CHALLENGE ― “Barf-o-Rama” Story from Stand By Me

Just as the food critic’s review is one step away from the actual meal, a rhetorical analysis is one step away from the initial piece the student read. Students read an article or listen to a speech and write their own piece (their rhetorical analysis) about what tools (rhetorical devices) the author used in the original piece to convey ideas and therefore, generate the modes (pathos, ethos, logos, and kairos) and how using those modes affects the reader’s understanding or ideas of the topic. Essentially, the rhetorical analysis argues whether or not the original author was effective in conveying the point and persuading the audience and the way it was done, much like a food critique argues whether or not the meal was satisfying and nutritious and the way it was done.

The food critic creates a writing about an eating and the rhetorical analyst creates a writing about a reading.

Works Cited

Babish Culinary Universe. Binging with Babish. YouTube, uploaded by Andrew Rea, 9 May 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=pw2A03Z91FI.

Bacharach, Samuel. “Julia Child’s Recipe for Entrepreneurial Success.” Inc.Com, 5 Jan. 2021,www.inc.com/samuel-bacharach/julia-child-lessons-for-entrepreneurs.html#

Barney, Tiffany. “Unpacking the Process of Rhetoric.” Open English @ SLCC. Pressbooks, 2016. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/the-rhetorical-situation/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021

Bird, Brad, Brad Lewis, Patton Oswalt, et al. Ratatouille. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Home Entertainment, 2007.

Jory, Justin. “Audience.” Open English @ SLCC. Pressbooks, 2016. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/the-rhetorical-situation/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2021

Jory, Justin. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Open English @ SLCC. Pressbooks, 2016. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/the-rhetorical-situation/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2021

Leighfield, Luke. “Advertising 101: What Are Ethos, Pathos & Logos? (2020).” Boords, 8 Sept. 2020, boords.com/ethos-pathos-logos. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020

“List of Food Preparation Utensils.” Wikipedia, 2 Feb. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_food_preparation_utensils.

Rapp, Christof. “Aristotle’s Rhetoric.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2010/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/.

“Rhetorical Device.” Wikipedia, 16 Apr. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhetorical_device. Accessed 30 Apr. 2021.

“Stylistic Device.” Wikipedia, 24 Apr. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stylistic_device. Accessed 7 May 2021.

The House Shop. “11 Obscure Kitchen Utensils That Are Actually Pretty Useful.” The House Shop Blog, 26 Oct. 2020, www.thehouseshop.com/property-blog/11-obscure-kitchen-utensils-that-are-actually-useful. Accessed 7 May. 2021

“The Soup Nazi.” Seinfeld, created by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld, performance by Jerry Seinfeld, Michael Richards, Jason Alexander, and Julia Louis-Dreyfus, season 7, episode 6, Castle Rock Entertainment, 1995.