Lisa Packer and Daniel Baird

INTRODUCTION

Community-engaged learning? Civic engagement? Service-learning? What are “designated” classes? Let’s start with a brief explanation of these terms that will be important to know before reading any further. Civic engagement is fulfilling your role as a citizen in your community and society through active participation in “civic life,” defined as “the public life of a citizen concerned with the affairs of the community and nation” (Center). Community-engaged learning (also referred to as service-learning) falls under the umbrella of civic engagement. It is when a student participates in an academic course doing meaningful community service that reinforces the learning concepts in the individual course. (See the article, “Introduction to Community-Engaged Learning.”)

You may have noticed that several English 1010, 2010, and 2100 courses are “designated” as Community-Engaged Learning courses. Why is this so, and what makes them different from a regular English 1010, 2010, 2100 course? An English designated community-engaged learning course:

- Combines academic study with engagement in “real-life” situations while writing, communicating, using critical thinking, researching and problem solving.

- Allows you to be meaningfully engaged while contributing to a community issue in collaboration with a community partner organization. This process encourages more authentic connection between your intellectual pursuits and a larger framework of understanding and action.

According to Barbara Jacoby, a Senior Consultant for the Do Good Institute in the School of Public Policy, students who engage in service-learning are more likely to achieve desired learning outcomes and master course material than those who opt for a more traditional course model (Jacoby). A designated English community-engaged learning course challenges you to not only learn academic material but to explore the practical application of that material in a way that benefits you and your community. These courses marry civic and academic engagement to help you explore the power of writing, the myriad purposes writing can fulfill, and the diverse audiences writing can reach.

I think that service this semester has helped me with my writing because it has shown me how personal experiences really enrich writing about a subject. It is easy to speculate about how volunteering at a service organization will help the community or help me as a person, but by actually doing it and writing about it after, I can see how the personal voice and experience makes the writing more credible to the audience. If I am writing about anything in the future, I have learned this semester that I can raise my ethos by engaging in an activity related to my writing. This can make my writing about those experiences relevant and more genuine.

—Jordan V.

Community-engaged learning also means you will develop specific writing skills and a greater awareness of writing contexts as you work with and serve others; in short, you will learn more about the impacts of the written word while serving a larger community.

COMMUNITY-ENGAGED LEARNING AND THE ENGLISH THRESHOLD CONCEPTS

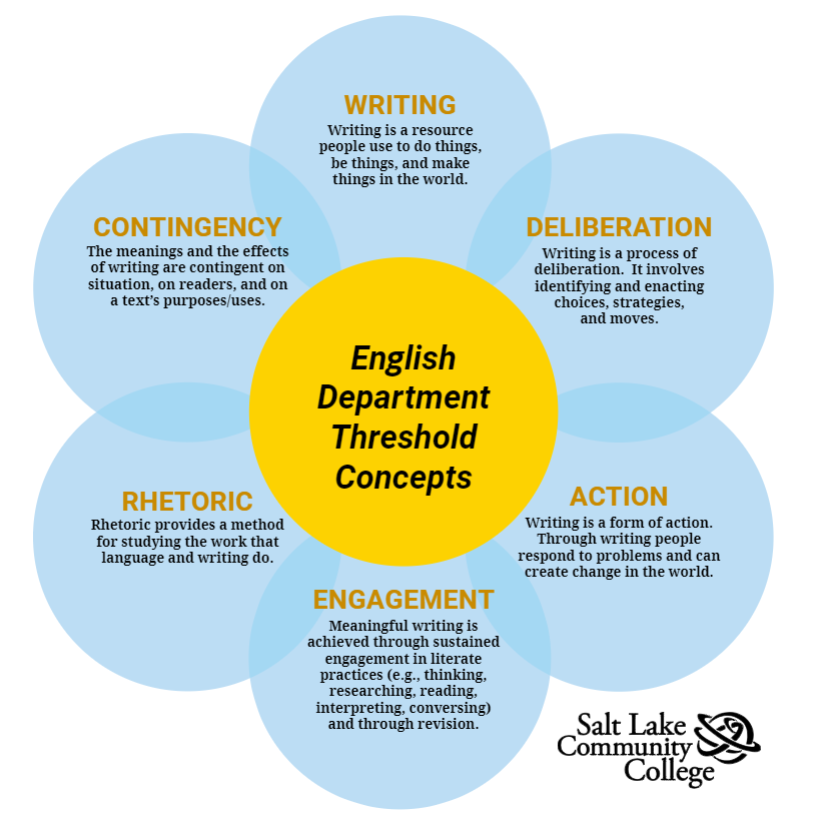

Below is a chart defining the six threshold concepts of writing, deliberation, action, contingency, action, rhetoric, and engagement. In this chart, “engagement” has to do with the process of writing. Most often we think of civically engaged writing as a form of action―a way to think about the community and enact social change within that community, whether the community is local, state, national, or global.

If you engage in a community-engaged learning English course, you will see the application of these concepts in real-world ways:

- How writing is a valuable resource with practical application

- How communities use rhetoric and how rhetorical analysis helps us to better understand our communities

- How writing becomes public action that directly impacts our communities

- How writing can be used strategically to create practical solutions to problems within our communities

- How the act of writing is to engage with one’s community

- How one’s community, and thus the writing within it, can look different depending on many factors

My engagement in service-learning this semester definitely influenced my writing. I learned that sometimes I need to look outside of the box and find a more creative way to approach topics. I also realized that sometimes I need to be more open-minded about topics or situations that I was sure of my knowledge on. It was an incredible experience for me, and one that certainly changed me for the better.

—Erika N.

WHAT ARE THE REQUIREMENTS FOR A COMPOSITION COMMUNITY-ENGAGED LEARNING COURSE?

So if you enroll in a designated community-engaged learning course, what will you have to do? How is it different from a regular English class?

In a community-engaged learning designated course, you will be required to commit a designated number of hours of service with a non-profit organization of your choice over the course of the semester. This may look differently depending on your instructor and their objectives for the course.

For example, by direction of your instructor, you may be asked to carefully select a community partner organization under the guidelines of that specific course. It will be important to keep in mind that your coursework during the semester will be informed by the work that you do for the organization as well as your personal reflections on this organization’s role in the community. The organization that you choose will come from the Thayne Center’s Community Partner database found on SLCC Campus Groups. This is the website SLCC uses to organize their database of community partners. It will also be the place where you log your service hours.

There were some feelings that I wanted to volunteer, do something better for other people, yet it needed self-push to make it happen due to too much concerns and fears of knocking the doors of unknown places. This class project actually eases these worries. It was really nice to have these organizations prepared and explained clearly to us. Also feeling like I’m not alone to make this new move, it was nice to have some shared feelings for this new start with a group.

—Emiko P.

CRITICIAL REFLECTION

Critical reflection is a crucial component of community-engaged learning/civic engagement. It is through engagement and critical reflection that you are able to see communities as learning contexts (Jacoby). You will also be asked to submit reflective writing throughout the semester about your experience with your community partner. Depending on your instructor and their objectives, the reflective prompts may look something like these:

- Describe your experience with your chosen organization(s) this semester. What did you learn? Did it fit or not with your expectations at the beginning of the course?

- How did your experience reveal or challenge your attitudes, values, and biases? Do you feel that your perspectives on your issue changed through working on the issue and writing about it?

- One of the core concepts of English 1010, 2010, 2100 is the following: “Writing is a form of action. Through writing people respond to problems and can create change in the world.” Relate the civic engagement experience this semester to your previous involvement in the community and society. How has the learning in this course shifted your understanding of community and society? How did your involvement in community-engaged learning and civic engagement this semester influence your writing?

- Now what? What changes can or will you make personally to address this issue in our community?

- Describe a few experiences and/or people you encountered during your service that/who left a strong impression on you. Why did they leave those impressions? What impressions do you hope you left on others? Why?

- How would you change established systems based on your community-engaged learning experiences? Explain.

This next section is an overview of how community-engaged learning works in the English composition courses. Feel free to skip to the course you are interested in learning about.

ENGLISH 1010 COMMUNITY-ENGAGED LEARNING

At a Glance

English 1010 community-engaged learning will motivate you to consider (and study) when, where, and how writing helps and hinders our engagement with others: other communities, other people, other practices, other ideas, and other values. In her book, Service Learning Essentials, Barbara Jacoby suggests that we think of service learning ― the combination of academic study with engagement in real-life situations ― as a text in and of itself. English 1010 encourages you to consider how “texts” come in many different forms, and how service to a community organization can serve as valuable field research into issues of local, national, and global concern. Ultimately, English 1010 community-engaged learning courses encourage you to discover how real-world experiences are the backbone of relevant writing (Jacoby).

In More Detail

As an introduction to both writing and service-based community engagement, the initial writing projects in the 1010 SL courses ask you to consider how writing enables someone to engage with their community, creating dialogues about past writing experiences with other students and instructors through structured online discussions and in-class activities. At the same time, there are open lines of dialogue with the community-partner organization where you will complete your service project, enabling you to learn about the issues faced and community needs addressed by the community partner.

Here are some of the ways you may do civic engagement in 1010:

- Analyze how writing is action and how to apply this concept in our own communities

- Open lines of dialogue with community partners to learn about the issues faced and community needs

- Develop writing projects that address a community-partner issue

- Log direct-service hours with a chosen community partner

- Engage in structured online forums and in-class activities and discussions

- Respond to reflective prompts to guide student conversations with each other and instructors

- Attend in-class lectures given by community partners, who guide on-site interaction and give individual feedback on student service projects and written documents

Examples of Past Student Projects

- Working with United Way to mentor and tutor elementary or middle school students in math or reading

- Aiding and helping those experiencing homelessness, such as through The Catholic Community Center opportunities, which include working with the St. Vincent de Paul meal program and the Weigand day shelter, helping sort donations, prepare meals, clean, or help with the laundry

- Helping recently resettled refugees and migrants with the International Rescue Committee, which opportunities include working at the Goat Kidding Farm, Spice Kitchen, and mentoring

- Volunteering at Clever Octopus, a creative re-use center, by sorting supplies, creating kits for educators, stocking the store, and organizing the warehouse

- Greeting students and stocking shelves at the Bruin Food Pantry for those students and staff experiencing food insecurity

ENGLISH 2010 COMMUNITY-ENGAGED LEARNING

At a Glance

Like its precursor, English 1010, English 2010 is based on the premise that writing matters. In this class, you will use writing not only to engage in daily personal activities, but also as a method of engaging with our respective communities on a larger level. English 2010 community-engaged learning courses take the English 1010 idea of writing as action and explore just how far we can bring our writing into our communities to create meaningful change ― in other words, we ask ourselves how writing is an inherent component of community and civic engagement, and we use our writing projects to question, study, and explore the idea of writing as a form of action in the world.

Just as English 1010 challenged you to view real-world texts using the lens of rhetorical analysis, in English 2010 you will learn how to synthesize real-world experiences and academic study.

In More Detail

Building on the model of writing as community engagement established in 1010, you, along with other students continuing on with community-engaged learning, will continue to expand community dialogues initiated in previous courses.

Here are some of the ways you may do civic engagement in 2010:

- Log direct-service hours with a chosen community partner

- Engage in in-depth research on social justice issues happening in the local community

- Participate in structured online forums

- Attend in-class activities and discussions

- Respond to reflective prompts to guide conversation with other students and instructors

- Attend in-class lectures given by community partners, who guide on-site interaction and give individual feedback on student service projects and written documents

As you, along with other 2010 students, move on to gather and shape materials to produce informational texts, practical proposals on community-partner issues, and multimodal commentaries, you broaden lines of community dialogue to include classmates, instructors, community partners, and community members.

Examples of Past Student Projects

Direct Service:

- Working with a local garden, harvesting the food that other students helped plant in the spring, helping with post-market surveys and analysis, interviewing and creating photo essays about the gardeners and working at their farmer’s market

- Preparing and serving a meal for Youth Resource Center clients with the help of the SLCC Food pantry and SLCC Community Garden; working collaboratively to create a resource guide of food pantries in the city, recipes for healthy meals made from food-pantry ingredients (and some recipes without the use of a kitchen), and other helpful information

- Attending a SLCC Alternative Break to make a constructive difference in the community through accessible, affordable, immersive service experiences regarding issues such as immigration, homelessness, food access and sustainability, animal rights, and more

Research:

- Find an issue/problem that needs improvement to help raise awareness, teach people how to do something, or market a solution to the issue/problem chosen for the semester. Choose to write a report detailing the problem, write a proposal explaining the problem and possible solution(s), or design a resource guide (pamphlet or website) to address the issue.

ENGL 2100 TECHNICAL WRITING COMMUNITY-ENGAGED LEARNING

At a Glance

Similar to English 2010 community-engaged learning courses, in English 2100 community-engaged learning courses you will learn how to synthesize real-world experiences and academic study by engaging with our respective communities on a larger level.

English 2100 teaches writing for your career whether you will be a scientist, an engineer, a nurse, or a computer programmer. Your class will combine your assignments with service in your community to enrich your learning about writing in your chosen career field.

In More Detail

In English 2100 you must complete two projects: the Writing Project and the Design Project. Each project has several options that you can choose from and one of those options is the civic engagement option. When deciding what service opportunity to pursue you should consider what social issues you care about or would like to learn more about and whether to choose online or in person service.

Here are some of the ways you may engage in civic engagement in 2100:

- Community Partners, or CP, (nonprofits) have a need and create a project for students to do on their behalf. This may include editing websites, creating videos, designing a brochure or other information materials, translating a document, etc. This is called indirect service because you are directly helping the CP, which in turn, then indirectly benefits those people or the cause that the nonprofit serves.

- You can volunteer with the community partner (CP) and directly serve the target population or cause that the CP espouses. For example, you may choose to tutor either math or reading to a K–12 class through United Way of Salt Lake or volunteer at the Maliheh Free Clinic to help provide free healthcare.

- Alternative fall or spring break also presents several opportunities from local to various out-of-state options for direct service.

Examples of Past Student Projects

Writing Project:

- Participating in weekend service helping with Youth Resource Center serving youth experiencing homelessness. Service included organizing the donation rooms and pantries to building shelves or cleaning and serving lunch to the youth. Students produced a proposal and a community-engaged learning journal.

- Writing grants for United Way of Salt Lake, Safe Harbor, and Teens Act, etc. to help these nonprofit organizations with continued funding.

- Directly serving many of these organizations by volunteering time such as with The Children’s Center or the Village Project and writing about their service or doing research. (A student wrote about the impact that math tutoring has had on Kearns high school students and submitted the report to United Way of Salt Lake City.)

- Assisting the Family Support Center over multiple semesters to update their policy and procedures manual.

- Translating documents from English to Spanish or other languages for organizations such as the Esperanza Elementary School, YMCA, and The Family Support Center.

Design Project:

- On behalf of Catholic Community Services, creating videos through interviewing and highlighting stories of those who are homeless and their struggle to erase the stigma of homelessness

- Creating a new website for Teens Act

- Creating flyers and other materials for organizations such as The Thayne Center, Bruin Pantry, Canyon Home Care and Hospice, The Inn Between, and the Boys and Girls Club

- Creating kitchen instructions for the St. Vincent de Paul Dining Hall of Catholic Community Services

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, as stated earlier in the English Threshold concepts, “Writing is a form of action. Through writing people respond to problems and can create change in the world.” By taking a designated community-engaged learning English 1010, 2010, or 2100 course, you can make this concept a reality. As stated in the Civic Engagement Learning Outcome Statement:

Students develop civic literacy and the capacity to be community-engaged learners who act in mutually beneficial ways with community partners. This includes producing learning artifacts indicating understanding of the political, historical, economic or sociological aspects of social change and continuity; thinking critically about—and weighing the evidence surrounding—issues important to local, national, or global communities; participating in a broad range of community-engagement and/or service-learning courses for community building and an enhanced academic experience.

Further Reading:

- The Department of English, Linguistics, and Writing Studies newsletter, Reflections, contains stories by students who have been involved in civic engagement including community-engaged learning classes.

- “Introduction to Community-Engaged Learning”

- “Writing For Community Change”

Works Cited

Center for Civic Education and funded by the U.S. Department of Education and The Pew Charitable Trusts. “What Are Civic Life, Politics, and Government?” Civiced.org, Center For Civic Education, 1994, www.civiced.org/standards?page=912erica.

Jacoby, Barbara, and Jeffrey Howard. Service-Learning Essentials: Questions, Answers and Lessons Learned. Jossey-Bass, 2015.