Tiffany Rousculp

I’ve been teaching composition for more than 25 years. Each semester, I ask students like you to provide “peer feedback” to each other on their drafts. And, each semester, I’m as disappointed as my students are in how it goes.

A few years ago, when I was introducing this part of the writing process, I said, “Today, we’re going to do a ‘fear peedback’ activity.” The room went silent. I stood still and whispered, “Did I really just say ‘fear peedback’?” Nervous laughter could be heard from all around the room.

This spoonerism was enough of a Freudian slip to show me that the way I was asking students like you to do feedback needed to change. I reached out to a compassionate teacher who was a semester away from retiring after three decades of teaching. She gave me wise advice, and it changed how I ask students to go about this important part of the writing process.

But first, let’s go through a few reasons why peer feedback often feels unsuccessful. You will probably find these to be very familiar.

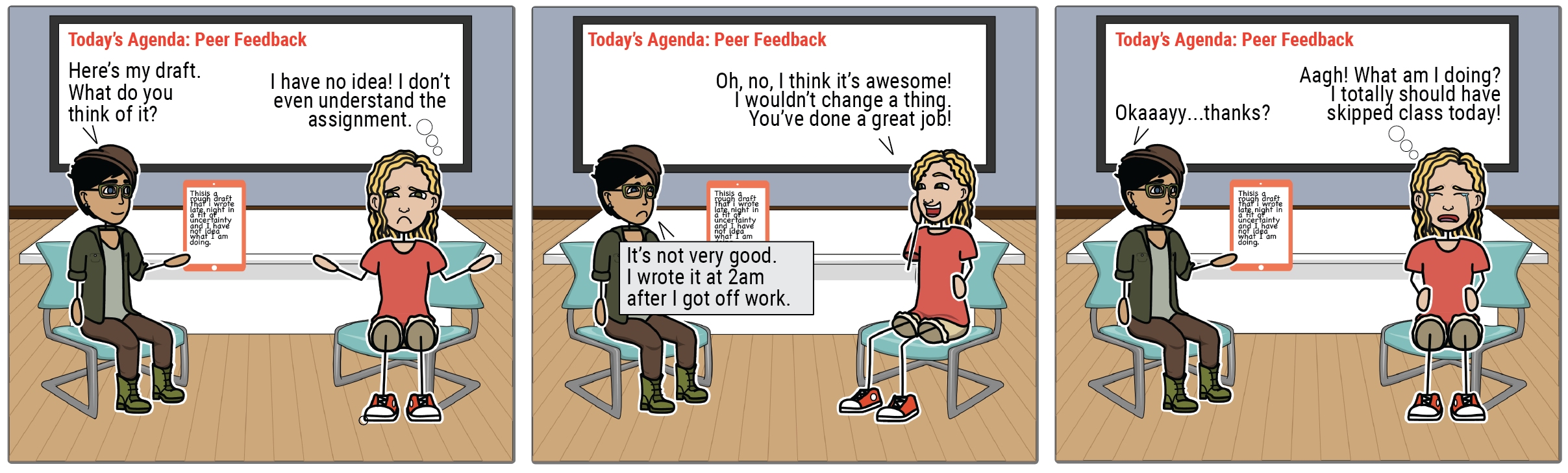

#1: Students often feel unprepared and insecure.

The nature of student-hood is that you are learning, stretching, and pushing your limits of understanding and abilities. When we are unsure about our own progress, we can feel like we are faking it when we give feedback to our peers. While a little bit of “faking it” is okay—and normal—when we don’t understand what we are doing, we can give fairly useless feedback to our peers. This makes them frustrated, and makes us wish we could disappear.

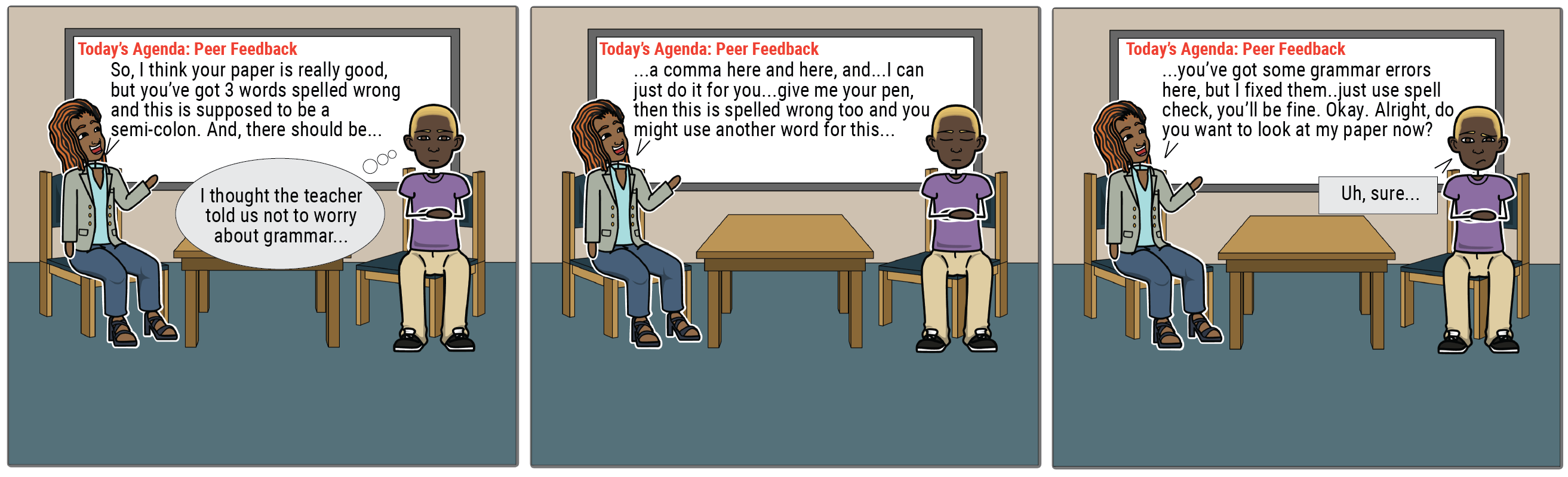

#2: Even students who are confident are unsure in giving feedback.

Sometimes we might feel confident in our own writing and even understand the assignment, but it’s still hard to give meaningful feedback to others. What often happens in this situation is too much talking, not enough listening, and too much giving “correction”-based feedback, which is not very useful at the drafting stage of writing.

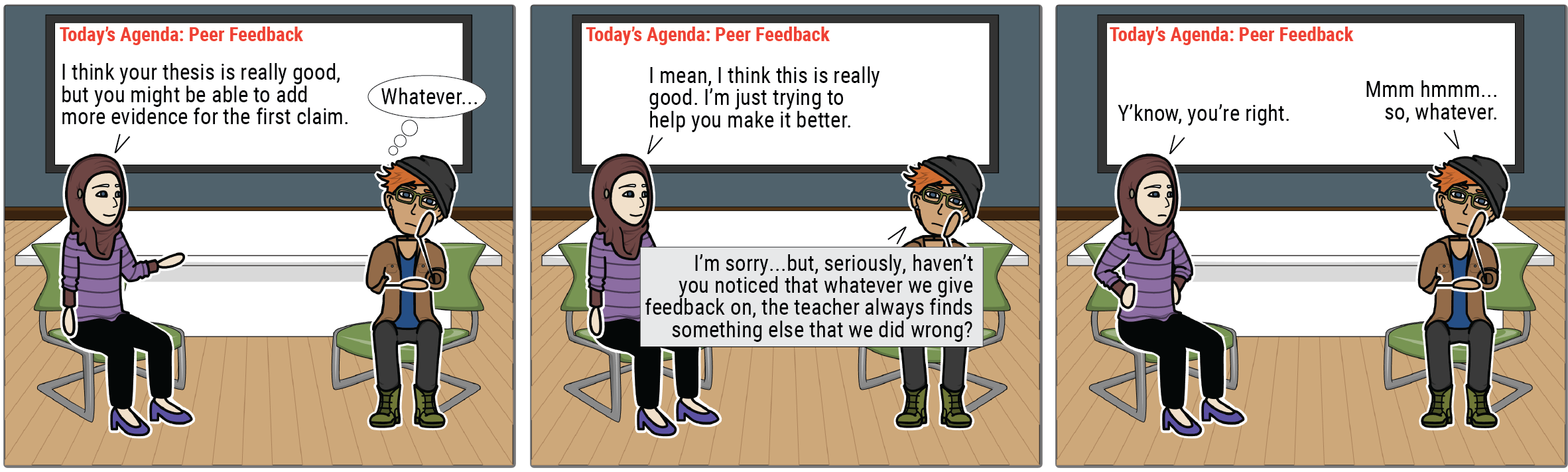

#3: Students are smart enough to know how the system works.

Even if we feel like we can give meaningful feedback on an assignment, all of us are smart enough to know that what the teacher thinks of our writing is what really matters (in terms of your grade). Since everyone will interpret a piece of writing somewhat differently, a peer might give you advice that your teacher disagrees with. Then, not only are you are confused by the different responses, you are also irritated by the peer feedback process.

CONSIDER THE CONTEXT

In contexts other than school, we might feel more comfortable giving writing feedback to someone. For example, at work, if you are experienced with a type of writing and someone asks you how to do it, you will likely have the confidence to provide meaningful feedback to them. Maybe you show them how to fill out a form or finish paperwork on a job. You give them advice and show them what they should do. They listen and learn and are appreciative of your help.

On the other hand, if you don’t know how to do what your colleague is asking, you’ll tell them that you don’t know or that you don’t feel like you can help them. Perhaps you will offer to figure it out together, especially if you also need to know how to do it.

In school, you’re most often in the latter situation because you are in “learning mode.” But, you’re not allowed to say that you don’t know how to do it because peer feedback means that you are supposed to help your peers improve their drafts, right? But, if you don’t know how to help them, then, well, let’s just say it can get very frustrating.

It’s within this context that we can provide each other with useful collaborative support on our writing. Like I learned from my colleague, the point is to change what may end up feeling like “fear peedback” into a positive experience for everyone involved.

COLLABORATIVE RESPONSE PROCESS

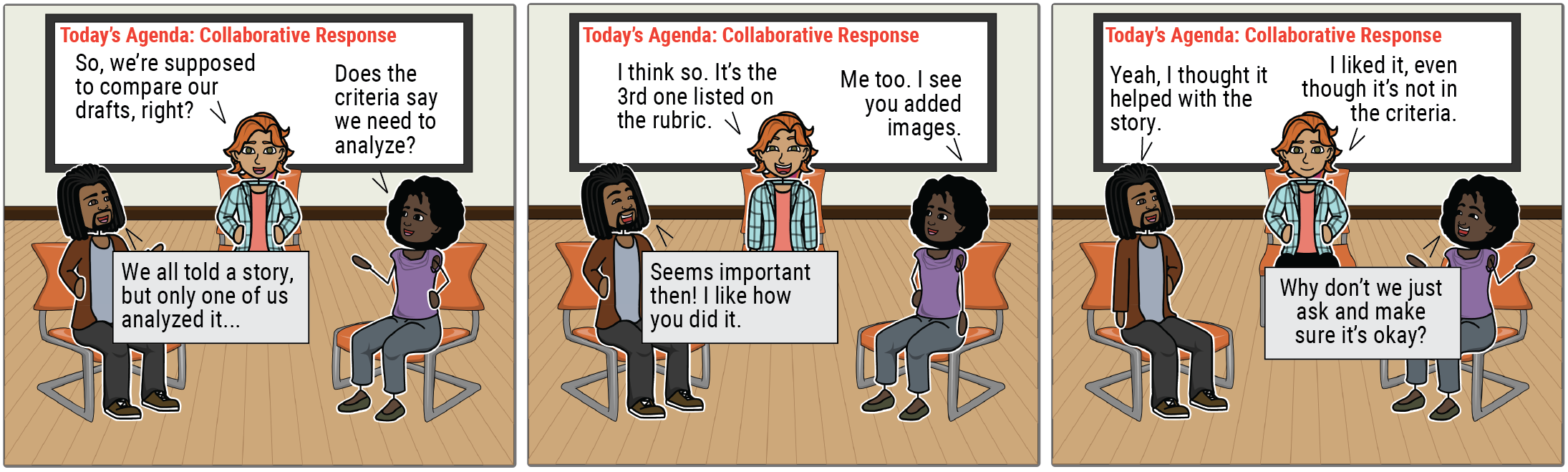

Instead of “peer feedback,” I call this process “collaborative response.” This may seem insignificant: just a two-word change. But, the key is in the word collaborative. No longer are you a student passing judgement on another student’s writing. You are working together, as a team, to understand an assignment’s expectations and support each other’s success.

In collaborative response, you will read each other’s drafts, but you won’t give each other advice on what they should do or how they could make it better. Instead you will

- go over the evaluative criteria with each other

- read each other’s drafts

- note how they are similar or different from each other

- analyze how the similarities and differences address the evaluative criteria for the assignment

In other words, in collaborative response, you compare your drafts to each other, not in terms of “how good” they are, but in how they approached the assignment’s criteria.

There is no correction, no “you should do this,” no “yours is so much better,” etc. The point of collaborative response is to share what you’ve done, get ideas from each other, and work together to understand how to meet the assignment’s expectations and criteria.

AND, WHAT IF WE DON’T KNOW WHAT WE ARE DOING?

The best part of collaborative response is that you are working together in a supportive manner, not in competition or judgement. So, if you don’t know something, you just ask the teacher! If you find that you have taken different approaches to the assignment, and you’re unsure what to do, explain the differences and listen to what the teacher has to say. It’s a conversation, not an evaluation.

Images created with StoryBoardThat.com