Anne Canavan

There’s an old joke about writing in English: “Tell ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em, tell ’em, then tell ’em what you told ’em.” While this may seem funny (or not, depending on your sense of humor), it is also a very accurate way of thinking about the way English-speaking readers want their texts to be organized. It is important to keep in mind that what works in English may not work in other languages. English is a writer-responsible language, so readers expect the writer to do all of the hard work of organizing ideas and presenting research [see the chapter “Writer-Responsible Language”].

We are taught from a young age that all writing needs an introduction and a conclusion (where we tell the reader what we are going to talk about and then remind the reader of the main points of the essay). Later on, we are taught the classic five-paragraph essay form, where we have a clear list thesis such as “Velociraptors make the best pets because they are intelligent, can find their own food, and are really good at guarding your house.” Then we develop one body paragraph about each of these main points. These types of essays are great for timed writing, such as tasks on the ACT or in-class essays, but they don’t give you room to add much complexity. For instance, what if you want to address the counter-arguments to your position, such as “velociraptors aren’t great pets because it is unwise to cuddle them”? The classic five-paragraph essay doesn’t give you much room to address those sorts of ideas, so we need to develop a more complex structure for our ideas.

WHAT DO I WANT TO SAY?

The first step to organizing your thoughts is to decide what information you already have, what information you need, what other people have already said about the topic, and what you want to say.

Thesis Statements

Most English writing begins with a thesis statement, even if you don’t actually put it in your paper. Because writers in English have to be so careful to help their readers follow the flow of the paper, English writing tends to be thesis-driven. This means that the main point of the entire writing can be stated in one or two clear, direct sentences, and these sentences often appear at the beginning of the writing. Once the writer knows his or her thesis statement, everything in the paper should go towards supporting that idea or argument. Even if a thesis statement does not appear in an essay, it should be easy for the reader to determine what the thesis of the essay is.

Word Webs

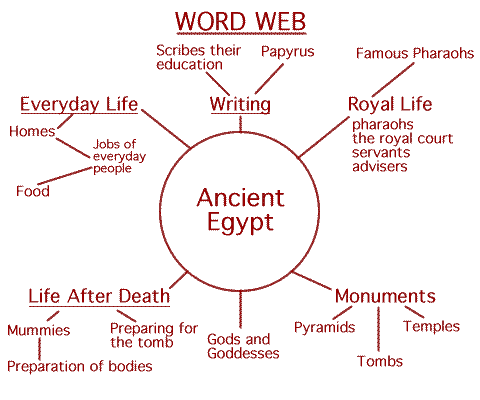

As you try to figure out what you want to say, one way of getting a look at your ideas is through creating a word web, as in this example from the Detroit Institute of Art:

Here, it is pretty straightforward to see the main ideas that the writer is going to address and if there are any areas that the writer might want to do more research on, such as, for instance, royal life. I recommend doing your first word web for a project in pencil, so you can move ideas around and make connections more easily.

Outlines

Another way to create a plan for writing is through making an outline for your topic where you can see the order of things you want to address. Below is a basic outline for a paper on how awesome velociraptors are:

And then you would continue the outline until all of your main points are accounted for. Again, I recommend doing your first draft in pencil, or with Word’s handy outline feature. One of the best things about outlines is that they can be done before you start writing to get a sense of your ideas, or after your paper is finished to make sure that your ideas flow together (called reverse outlining). Typically, reverse outlining involves gathering the main ideas from each your paragraphs and checking them to see if you have repetition or ideas that are out of place.

Paragraphs

Speaking of paragraphs, it is a good idea to make sure that your paragraphs are doing their jobs. While you may have been taught in grade school that a paragraph is always 3–5 sentences, this idea (like many others) gets more complicated as you get older.

The primary job of a paragraph is to develop ONE idea fully. Sometimes that may mean that your paragraphs are short, and other times it means they may be as much as a page in length. In general, if you read back over your paper and you see a paragraph that seems very short or very long, go back and double check that you only have one idea at play in that paragraph, and that it is being fully developed. Ideally, you should be able to summarize a paragraph in a few words or a single sentence. Some writers will even go back through their first drafts and label each paragraph with a brief summary to make sure the idea is clear. Having clear paragraphs is also the best way of building transitions from one idea to another.

Transitions

Since English is a writer-responsible language, English readers expect a lot of the work of idea connection to be done for them in a clear manner, usually by using transitions. Transitions range from very simple (however, next, therefore) to more complex sentence or paragraph transitions. No matter how simple or complex, a transition does one basic job—it shows a reader how two ideas are connected and leads them from one idea to another. One way to think about transitions is as bridges. Imagine that your two ideas are the opposite sides of a river, and you need to help your reader cross. The farther apart your ideas, the stronger your transition needs to be.

So let’s think of our raptor outline from before. We need to form a transition between the idea that raptors are great guard animals to the fact that they are intelligent.

The transition above works, but it is pretty boring and doesn’t give the reader much insight into why you connected these ideas together.

This slightly longer transition reminds the reader of the main idea they just read (guard animals) and gives them a head’s up as to where the paper is going next, as well as demonstrating the logical connection between the two ideas.