Stacie Draper Weatbrook

I received this text from my neighbor:

I was baffled. I hadn’t heard from my neighbor since the day before, when we were coordinating carpool. I had no idea what this random text meant. To speak in rhetorical terms, I had no context. There were no other messages she’d sent that were contingent to this new, cryptic text. Before I could respond with a question mark, she quickly texted again:

My neighbor, whose grandmother lived with her, meant to text the home health nurse. It was important for the nurse to know the status of grandma’s digestive tract, but my neighbor mistakenly clicked on my name in her contacts instead of the nurse.

Have you ever received a confusing text?

These mishaps occur frequently when we text, and they are often humorous because, as readers, we expect what we read to make sense. When you write something, you’re basically making a contract with the reader. You’re saying,

If you read this, I promise to make sense.

It’s an unspoken contract, but readers and writers rely on it. It’s like when you get in the car with a friend. You expect they will drive safely and go where you both agreed to go.

The road metaphor is a good one when considering how to make sense to your audience. Two ideas about how to make sense to your reader as they take a trip through your paper are to use a thesis as your roadmap and to use “quotation sandwiches” to integrate sources.

YOUR THESIS IS YOUR ROADMAP

Don’t Leave Your Readers Stranded in Scipio: Map Out Your Essay with a Thesis

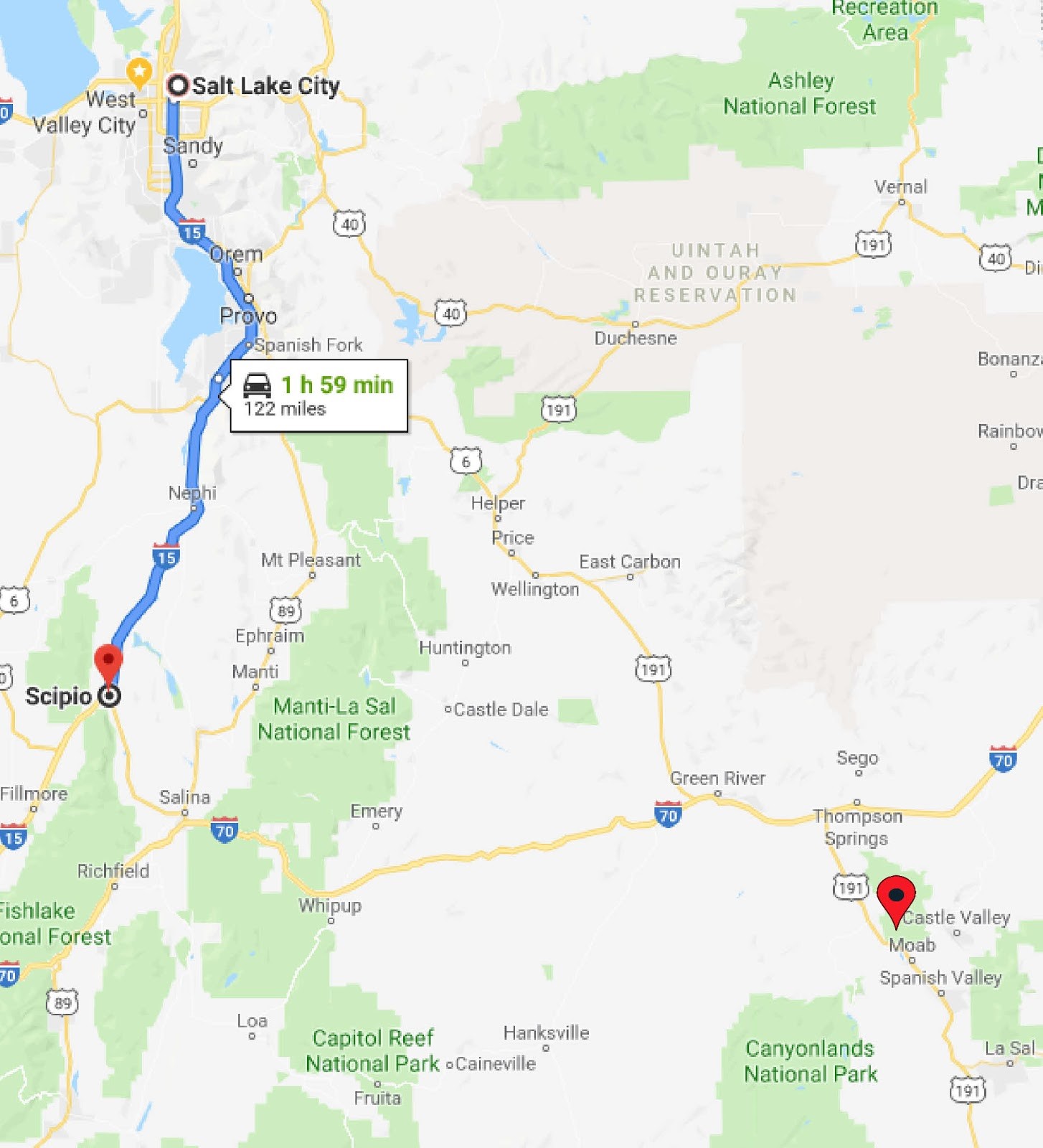

In the days before Google Maps, when you went on a road trip, you needed to know the route. Say you’re going to Moab from Salt Lake. You’d need to know to travel through Provo, then Spanish Fork, and—this is important—take the Highway 6 exit from I-15 at Spanish Fork. Highway 6 will lead to Helper and Price, where it merges with Highway 191 and leads to Green River and then on to Moab. You’d get the general idea in your head and mentally check off each town as you passed.

On one road trip, my friends and I missed the exit for Hwy 6 that led to Price. We found ourselves 70 miles down I-15 in Scipio and, after stopping at one of the only two gas stations for instructions, realized we’d added 74 miles and an hour to our drive.

It was an adventure.

Your audience, often your instructor and peers, aren’t likely to be as adventurous. In fact, if you tell them you’re going one place and then go somewhere else, they may feel hijacked, or at the very least annoyed. Academic writing is usually not a whimsical road trip. It’s more like your audience needs a ride to their job interview and they need to get there on time. Your thesis is your roadmap.

When composing your thesis, think:

What do I want my audience to know or think when they are done reading my paper?

Answer this question, and you’re on your way to a good thesis. Your thesis will probably change many times as you are composing and drafting, but in your final draft, the destination should be clear. Don’t forget the map and the destination in the course of writing your paper!

Your thesis outlines the essay. Consider this thesis for a rhetorical analysis paper, a paper that talks about the writing style of a document rather than the subject of that document:

A few things to notice in this thesis: First, it’s longer than a sentence. Having a thesis statement that’s actually a paragraph may feel weird, but it’s perfectly acceptable. Second, it uses “guiding words” to show what the paper talks about and in which order. Just as map will show you to drive through Provo, Spanish Fork, Helper, Price, and Green River to get to Moab, if your audience is told they will be passing through Ethos, Pathos, and Logos, you’d better deliver and in that order.

Your thesis will help you set up a map or outline of the paper. The points in your thesis will be the sections of your outline.

DESTINATION (Thesis):You and your passengers have all agreed to go to Moab, and they trust you as the driver to take them there. (You should arrive in Moab without delays or detours.) |

THESIS (Destination):Anne Lamott is effective in helping her readers know they don’t have to write perfect drafts. (By the end of the essay, readers should see that Anne Lamott is effective.) |

MAPPED ROUTE (Outline):

|

OUTLINE (Mapped Route):

|

Don’t confuse major points for paragraphs. According to the outline above, the rhetorical analysis essay will have three major points: ethos, pathos, and logos. To properly cover the subject, you’ll want to have a few paragraphs for each of the points.

Think of each point in your outline as a town on the map. You’ll give your readers a topic sentence, or point sentence, about each of the “towns” listed in the thesis. On your way to Moab you might say to your passenger as you approach Helper,

We’re coming up on Helper. It used to be where the railroad would add an extra engine to help the coal trains make it up the mountain.

Use point (or topic sentences) to signal your discussion of each point in the thesis. The passenger knows to mentally check off one of the points on the map. Topic sentences are signals in the body of the paper to the reader that you are keeping your promise to discuss what’s in the thesis or to help lead the reader logically through your thoughts.

Point one:

Then you’d give several specific examples from the text and explain (analyze) why they are examples of credibility or ethos. One way to organize your paper is to give each specific example its own paragraph.

Point two:

Again, in this section of the analysis, you’d give several specific examples from the text and explain why they are effective examples of pathos or emotion.

Point three:

Here, as you discuss the last portion of the thesis, you’ll also give several specific examples and quotes from the text and explain why they are appeals to logic or logos.

Notice that each of these sentences mirrors and explains the ideas in the thesis statement.

PACK SNACKS: USE THE “QUOTATION SANDWICH”

So far, we’ve talked about having an outline and using topic (point) sentences along your journey. There’s a lot to fit in between points A and B and B and C. You’ll want to integrate sources to back up the points you make in your thesis (which are now the topic sentences). Think of it as packing a sandwich for your readers to munch on during the ride.

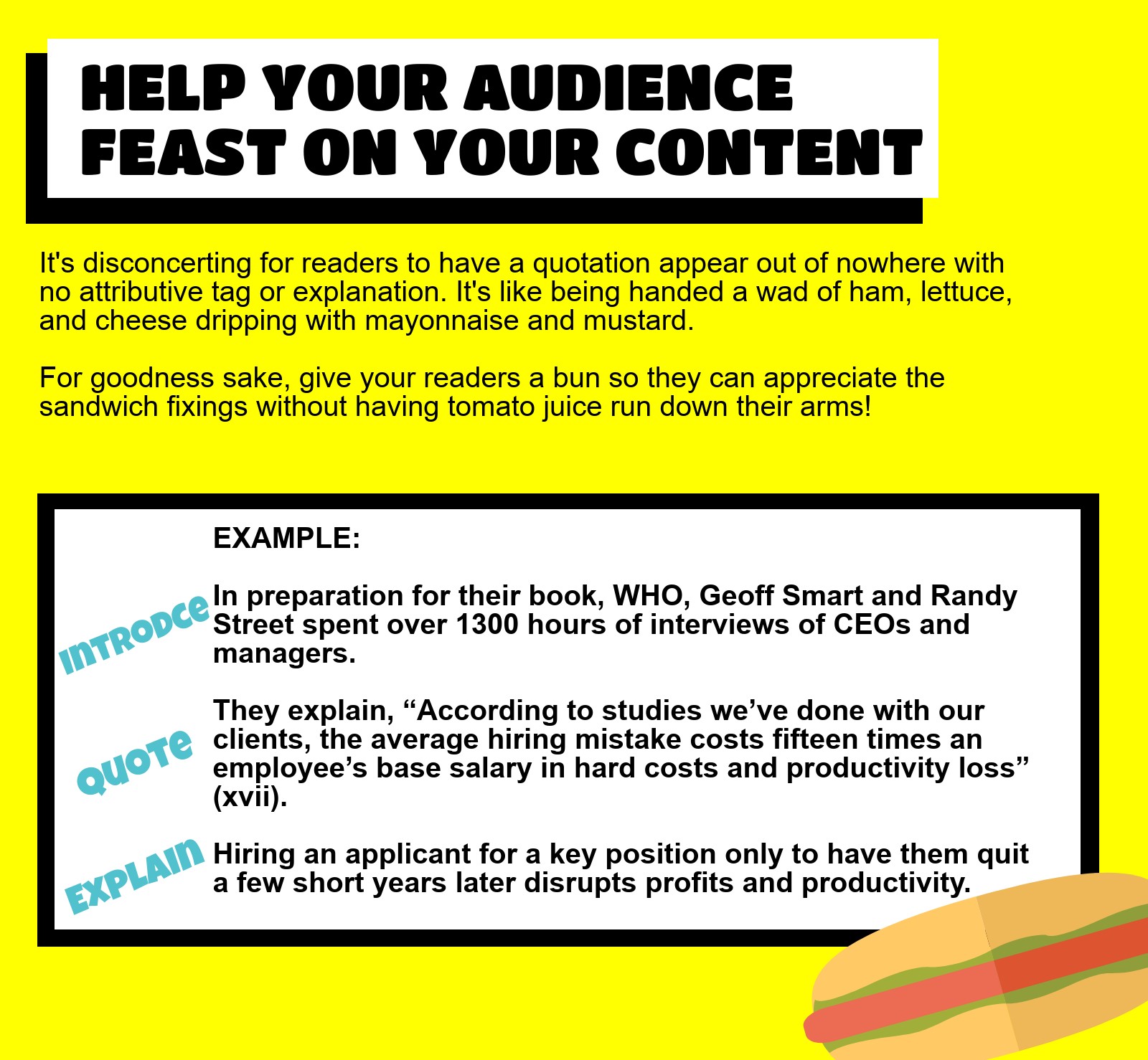

A sandwich, as you are well aware, has bread surrounding meat, cheese, veggies, or PB&J. The bread makes it easy to eat. It’s the same when adding sources to your paper: you want the information you give to be easily digestible for the reader. You want it to make sense. Gerald Garff and Kathy Blinkenstein give a solution for integrating sources. In their book, They Say I Say, Garff and Blinkenstein tell readers to use “the quotation sandwich” (46). Sandwiching quotes between an introduction—which includes an attributive tag naming the author(s)—and an explanation helps the reader see how the quote you included supports your overall thesis and the immediate point you’re trying to make.

Readers find it disconcerting to have a quotation appear out of nowhere with no introduction or attributive tag and no explanation. It’s like being handed a wad of ham, pickle, tomato, lettuce, and cheese dripping with mayonnaise and mustard. It’s going to run uncomfortably down your riders’ arm and most likely make a mess on your car’s upholstery. The solution for eating sandwich fixings is bread (or lettuce or flatbread, if you’re going for a wrap; you get the idea.) In writing, sandwich your sources in between an introduction and an explanation.

Here’s what a quotation sandwich might look like:

Here’s a play-by-play recap of how the quotation sandwich works:

Topic sentence (following the order given in the thesis):

Analysis and ideas about the essay from the writer of the rhetorical analysis:

The introduction―the bread on the top of the sandwich:

The quote―the fixings between the bread:

*I’ve shortened the quote. The ellipses (…) show readers I omitted some parts of the original essay.

**This quote came from a printed book, so this number is the page where I found the quote. If you are writing from a source that doesn’t have page numbers, you will not include page numbers. It then becomes even more essential to include the attributive tag to let your readers know where the quote or information came from.

The explanation―the bread on the bottom of the sandwich:

The quotation sandwich isn’t just for direct quotes. It is not only helpful but also avoids plagiarism to use this same pattern when discussing any information you get from sources:

***The ideas in the sentence are Lamott’s. Even though I didn’t directly quote her, I need to use an attributive tag to properly credit her as my source, and, since there is a page number available, I use it. When we are clear about attributing quotes and ideas, we also make it clear to our readers that the sentences without an attributive tag are our own brilliant analysis of the text and subject.

CONCLUSION

Remember, you are the tour guide of your paper. It’s your job as a writer to help your audience know where you’re going, which points you’ll pass through, and why they are significant.

Giving your audience a map, or a thesis, is giving them the big picture of what you want them to see. Continue to remind your audience often of that big picture. Just as important as keeping the big picture in mind is letting your audience know when you reach each of the said points by using topic sentences.

When we think of writing as driving our reader efficiently to a destination, we’re able to see the importance of a mapped-out route. Along the way, we provide our reader with snacks (quotation sandwiches, anyone?) they can easily digest. After all, no one loves being lost in Scipio and no one loves cleaning a greasy mixture of pickle juice and mayonnaise from their car seat.

Works Cited

Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. New York: Norton, 2012. Print.

Lamott, Anne. “Shitty First Drafts.” Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. New York: Random House, 1994. Print.

Smart, Geoff and Randy Street. Who: The A Method for Hiring. New York: Ballentine, 2008. Print.