Tiffany Buckingham Barney

You’ve likely done peer review before in high school, in college classes you’ve already taken, or even at work, but as you start doing peer reviews in a college writing class, it might be time to reframe your approach. While you have probably offered feedback on the subject of a paper and maybe even the punctuation and spelling, it is less likely that you’ve been instructed on how to prioritize your feedback.

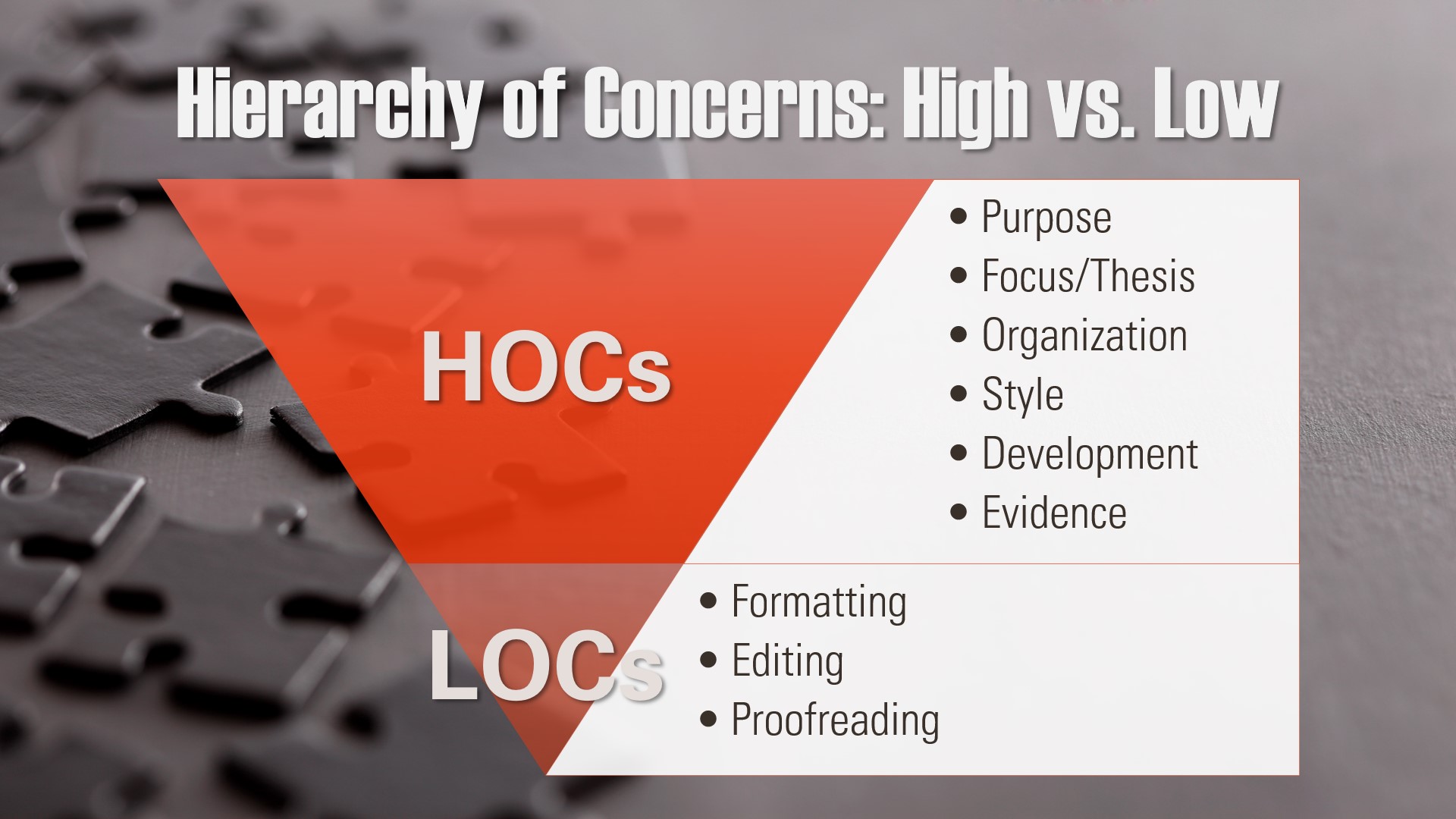

Considering the fact that most college writing centers are comprised of student (peer) tutors, writing center study is a good place to start. For a number of years in writing center studies, there has been much conversation about higher order concerns (HOCs)―concepts that carry the most weight in a paper―and lower order concerns (LOCs)―concepts that generally carry the least weight in a paper―in order to direct tutors to focus on what matters most first. This can also help you, the writer, as you draft, review, and revise your work, to focus on what matters most first.

The Student Writing and Reading Center at Salt Lake Community College (SLCC) uses this framework for assisting students. When you sit down with a writing tutor, they’ll ask for the assignment prompt right away. This is because SLCC’s tutors know they could spend an hour with a student focusing on punctuation and spelling issues only to have the student fail the assignment because it was supposed to be on an entirely different topic. SLCC’s writing center tutors know to focus on the higher order concerns (HOCs) first, like following the assignment prompt, and the lower order concerns (LOCs) last, like punctuation and spelling.

You, as a writer (drafter and reviser) of your own piece and the reviewer of others’ pieces, may save significant time and effort by paying attention to this same order of concerns. Recognizing the writing prompt as the most important element and the grammar and punctuation as the least important can help you focus your efforts.

Purdue’s Online Writing Lab (Purdue OWL) is a well-known online writing center that’s become a go-to online source for everything pertaining to the tutoring of writing. They list the following as “some” HOCs: thesis and focus, audience and purpose, organization, and development. Also, they list the following as “some” LOCs: sentence structure, punctuation, word choice, and spelling. Notice their use of the word “some” in order to stipulate these are not “all” of the concerns of writing and also to leave room for minor variation among genres. (For example: technical writing places formatting as a higher order concern since the formatting is used for quick-glance understanding, which is a genre identifier.)

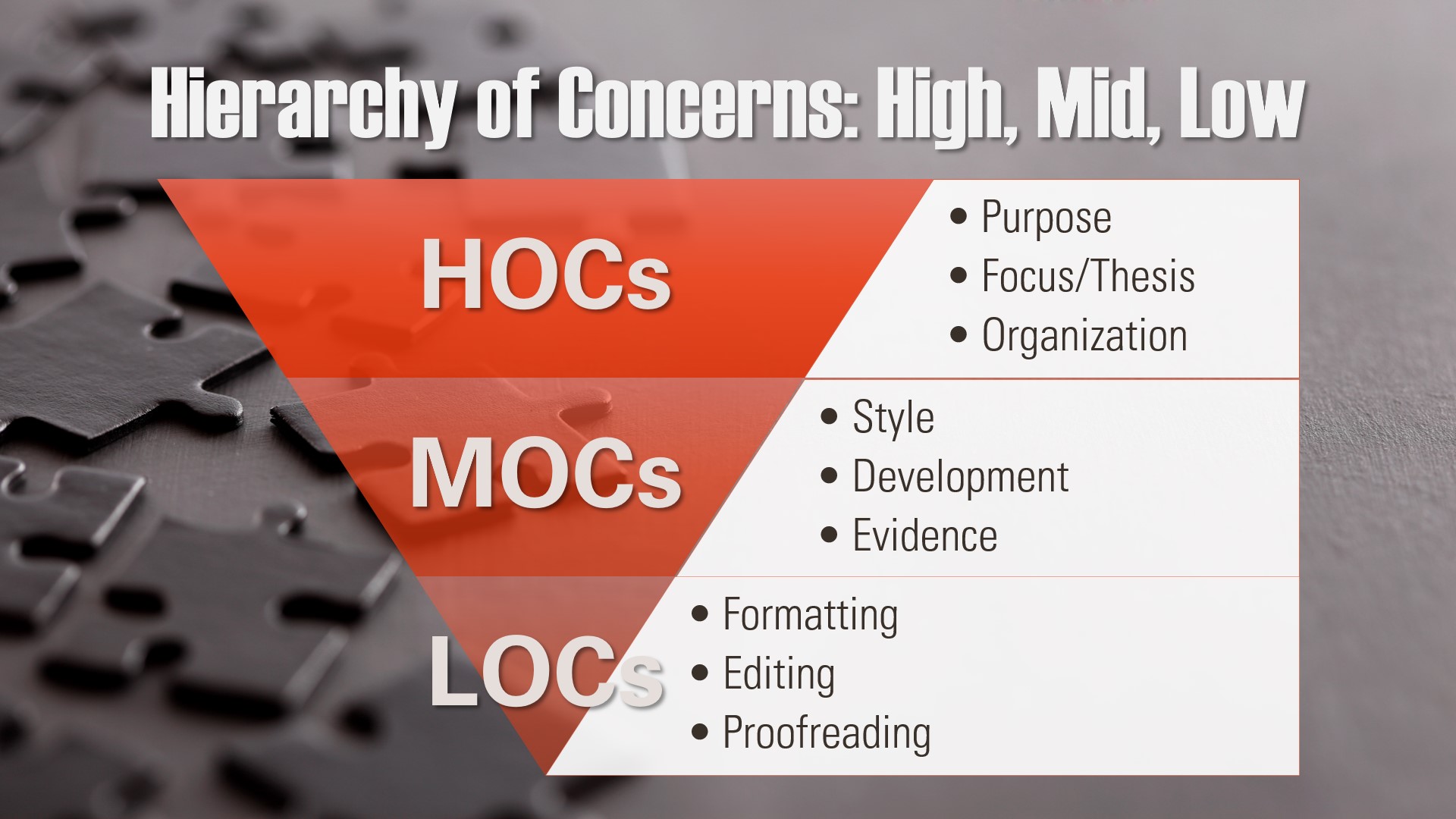

To convey these ideas, HOCs and LOCs are often drawn as an inverted pyramid. This type of illustration indicates three things about the items at the top of the list: they should come first, they are bigger concepts, and they are the most important. The opposite is true for the items at the bottom of the list.

Shifting Concerns

In the 1984 introduction to HOCs and LOCs, “Training Tutors for Writing Conferences,” authors Thomas Reigstad and Donald McAndrew divided concepts into only the two categories, and the point was to emphasize that LOCs like grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc. were just that: lower order concerns. Everything else fell into the HOCs category.

Later, in a 2001 book, Tutor Writing: A Practical Guide for Conferences, Reigstad and McAndrew make the further distinction of HOCs being rhetorical concerns and LOCs being rule-based concerns. Rhetorical concerns are elements that come from or are related to the rhetorical situation like audience, purpose, writer, exigence, subject, and genre. Rule-based concerns are just that: based on rules like spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

It is important to note, however, that rule-based concerns, LOCs that is, can become HOCs when they impede the audience’s ability to understand the text. Consider the following rare situations coming from the LOC category and moving to the HOC category.

- Spelling ― Words can be spelled so poorly that they cannot be recognized even within the context of the sentence.

- Punctuation ― Punctuation can be so ineffective that it can create ambiguous meaning or even put a full-stop to comprehension.

- Grammar ― Grammar can be so underdeveloped that a paper becomes unreadable.

Also, a number of instructors are highly aware of LOCs and may have a difficult time reading a paper with spelling and punctuation issues. There are even some instructors who use LOCs as a sort of passageway to grading, requiring papers to be formatted correctly in order to accept them. Sometimes this is done as a weed-out measure, but more often it stems from a distraction issue. It can become difficult for some instructors who are hypersensitive to grammar and spelling to read a paper and understand its message when all they notice is the formatting and spelling issues. This is why it’s important to be aware of how your instructor views these concerns.

Still, while LOCs may hold power in some classrooms, they aren’t the element that differentiates between a good paper and an excellent paper, since both can have perfect formatting and editing. Also, you’ll certainly want to have given HOCs the weighty attention they deserve once you get your instructor reading your paper.

Although Purdue OWL and many others still follow Reigstad and McAndrew’s model of the two categories, HOCs and LOCs, Duke University’s Writing Studio has published a handout, “Revision Strategies: HOCs and LOCs,” that includes a third category of middle order concerns (MOCs).

MOCs are rhetorical elements that can take a paper from mediocre to incredible and have the power to intensify delivery of a message; they have the capability of being profound. The style of delivery, development of ideas, and application of evidence can all be done haphazardly or profoundly or anywhere in between. This sliding scale of quality is what qualifies elements to be in the middle order of concerns (MOCs) category. In a well-written paper, these are the elements the author gives the most time and attention to once the HOCs are addressed.

Middle order concerns (MOCs) have traditionally been classified as HOCs in these graphic images, but here and in the following explanations, they are divided into their own category.

Higher Order Concerns (HOCs)

In a tutoring session, one of the first things a tutor will ask the student writer is “What is the assignment?” There’s good reason for this. If your instructor has asked you to write a rhetorical analysis of an article they’ve chosen but you wrote about last summer’s trip to the Chocolate Hills of Bohol Island in the Philippines, you may have some beautiful prose and impressive grammar in that writing, but you won’t get a decent grade―or possibly any grade at all―no matter how well it’s written.

The purpose for writing the paper falls into the HOC category. Higher order concerns are things that make or break a paper. They categorize the paper in the right genre with an appropriate audience and correct purpose, identify the focus of the piece with a thesis, and formulate an organization that presents the paper clearly.

Higher Order Concerns (HOCs)

Purpose ― This comes from the assignment prompt, which should detail what to write about and how to write it, including reference to genre and audience. (NOTE: It is assumed that assignment prompts are asking for a student’s own original work as well.)

Focus/Thesis ― A thesis tells your reader what your paper will focus on. Your paper should then follow through with that focus.

Organization ― Oftentimes, the organization for the paper is given in the instructions. Other times, organization can be gleaned from viewing other pieces within the genre. Sometimes organization is specific to the topic you have chosen. All the time, organization affects the comprehension of your paper.

When drafting your paper, HOCs should be your primary focus. Although the drafting process can look different for many writers and even for many of the different papers you’ll write, once the HOCs are in place is when you, as a writer, have a draft that is formulated well enough to review.

When reviewing others’ papers, these are the elements to look for first. Just like a writing tutor asks for the assignment prompt, you, as a peer reviewer, look for the response to the assignment prompt in your peers’ writing. If these elements are not found in the paper, the remainder of your review will be spent discussing the assignment prompt and assignment requirements.

When revising your own paper, if these HOC elements are not present, you may be able to use some of what you already have, but you might also consider rewriting at this point.

When your paper is being graded, these are the most important elements and will have the most weight. If a paper is the wrong topic or genre, or has no apparent focus or organization, you may receive a very low score, be asked to rewrite your paper, or even receive a zero with no option to rewrite. These elements are that important.

Middle Order Concerns (MOCs)

If you still insisted on writing your paper about your trip to the Chocolate Hills of Bohol Island, any of your middle order concerns (MOCs) work would be for naught because the HOCs weren’t addressed first. If your assignment had been to write about last summer’s vacation, your MOCs would then get moved onto that sliding scale for grading because your HOCs are already met.

The following are middle order concerns because they are the elements which can be on that sliding scale and take a paper from simply fulfilling the requirements and getting good credit to making an outstanding argument for full and even additional credit.

Middle Order Concerns (MOCs)

Style ― Using tone/voice in an appropriate manner can give you credibility as an author and keep your audience’s attention. Choosing words carefully can help clearly convey ideas.

Development ― Adequately developing ideas includes using logic and reasoning. It also shows a coherent flow of ideas and that those ideas are argued through in their entirety.

Evidence ― Using credible sources appropriately and effectively gives you evidence for your claims and shows you are willing to give credit where credit is earned. Citing those sources also shows that you can follow instructions for citation.

When drafting your paper, be sure to allow your ideas to develop fully and those style elements to flourish even if your draft ends up too long at first. You can edit for length later, but may want to hold on to some of those original ideas because they may be what moves your paper towards something outstanding.

When reviewing others’ papers, look at these elements only if the paper has successfully fulfilled the higher order concerns. If they have, look for things that can help the student improve the items within this category.

When revising your own paper, look at these elements after the higher order concerns are addressed. See how you can take your paper from one that only fulfills the requirements to one that executes a compelling argument with appropriate tone/voice and convincing evidence.

When your paper is being graded, these are the elements that distinguish one paper from another. These elements show your competence as a writer in ways that can bump up your score from a B to an A, etc.

Lower Order Concerns (LOCs)

Imagine finishing your elegantly written paper about last summer’s trip to the Chocolate Hills of Bohol Island and then spending hours correcting grammar, fixing spelling errors, and checking punctuation in order to get all the lower order concerns (LOCs) perfect only to receive a very low grade if any grade at all because what you didn’t write was a rhetorical analysis of the teacher’s chosen article. Although you had a great independent study session about grammar, spelling, and punctuation, you still have another paper to write. Oftentimes students spend too much attention on LOCs early on, making them extra attached to drafts they won’t end up using.

These rule-based concerns don’t change any of the rhetorical features of your writing. This distinction allows us to categorize the following as lower order concerns.

Lower Order Concerns (LOCs)

Formatting ― MLA is a very common formatting style used in English classes. APA is often used as well. There are times when your instructor or department will give you a specific formatting style to use. You can do this first or last, but spend any extra effort on it very last, after all sentences and paragraphs are where they are going to stay.

Editing ― Some students prefer to edit as they go, but be careful not to let that interrupt your flow of ideas. Editing includes changes to spelling, punctuation, grammar, and word usage.

Proofreading ― The very last step, regardless of how good you are at editing, is to proofread the document. Frequently when revising or editing, particularly when changing word choice, words can get jumbled and punctuation can get lost. Proofreading catches the errors created when fixing errors.

When drafting your paper, your instructor may grade lightly or harshly or anywhere in between on these elements; however, your focus on them, whether intense or not, should happen toward the end of your writing process in case you end up changing quite a few sentences or paragraphs along the way.

When reviewing others’ papers, unless the LOCs impede understanding, these are certainly the last elements to consider. Although you may have encountered prescriptive grammarians who over-emphasized the importance of LOCs, these elements should be kept in their place in a review―at the end.

When revising your own paper, you may be a writer who prefers to format upfront and correct grammar and spelling as you go. If you are, be sure to double check at the end. If you’re not, revise your ideas first and handle the lower order concerns last.

When your paper is being graded, whether your instructor/grader puts a lot of emphasis on these elements in their grading or not, they may notice mistakes with these elements that can sour how your paper is read, so although these are the last elements to put energy towards, they still matter.

Using Order of Concerns to Think

All of these elements, put in their proper place, can help you, as a student, have focus in drafting, purpose in reviewing, guidance in revising, and goals in being graded. Viewing each for what it is―a rhetorical choice or a rule to follow―can further help you focus on formative development in your writing by spending more of your efforts developing your ideas. Also, knowing how the assignment points are allocated is important. Major points are lost in failing to address higher order concerns; many points can be lost or gained in how you handle middle order concerns; and, depending on your instructor, various points are lost on errors with lower order concerns, but good writing is not easily concealed by lower order concerns.

Prioritizing the hierarchy of concerns―by addressing the higher order concerns first, middle order concerns second, and lower order concerns last―will help you become a formative writer and thinker, developing your cognitive learning and metacognition. This is yet another reason why we write.

References

Cross, S. and L. Catchings. (November 2018). “Consultation Length and Higher Order Concerns: A RAD Study (1)” found in WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship.

Duke University. (October 2021). Writing Studio Handout: Revision Strategies HOCs and LOCs. https://twp.duke.edu/sites/twp.duke.edu/files/file-attachments/shortened-hoc-v-loc-handout-1.original.pdf

Huett, A. and Dr. R. T. Koch Jr. (May 2011). “Overview of Higher Order Concerns.” UNA Center for Writing Excellence. https://www.una.edu/writingcenter/docs/Writing-Resources/Overview%20of%20Higher%20Order%20Concerns.pdf

Purdue OWL. (Accessed October 2021). “Higher, Lower Order Concerns // Purdue Writing Lab.” https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/mechanics/hocs_and_locs.html.

Reigstad, T. J. and D. A. McAndrew. (1984). Introduction to HOCs and LOCs, “Training Tutors for Writing Conferences,” https://eds-a-ebscohost-com.libprox1.slcc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=4915d6fd-3ee3-47d1-bfe6-9bb51d76a811%40sdc-v-sessmgr03

Reigstad, T. J. and D. A. McAndrew. (2001). Tutoring Writing: A Practical Guide for Conferences. Accessed via Institutional ProQuest October 2021.

Rickly, R. “Reflection and Responsibility in (Cyber) Tutor Training: Seeing Ourselves Clearly on and off the Screen.” In Wiring The Writing Center, edited by Eric H. Hobson, 44–61. University Press of Colorado, 1998. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt46nzf8.7.