Just like you drive for the conditions, you also write for the conditions. Here are some ways to keep your audience along for the ride.

Stacie Draper Weatbrook

DRIVE FOR THE ROAD CONDITIONS; WRITE FOR THE READER CONDITIONS

You can’t drive the same way all the time. You start and stop when you’re in traffic, and you can go 80 mph or more on the open Interstates. When you’re driving in the mountains, you don’t take curves at 50 mph. Instead, you slow down to avoid careening off the cliffs. In the rain, you reduce your speed to avoid hydroplaning. When driving in the snow, you reduce your speed, you keep a big distance between your car and the other cars, and you don’t break quickly so your car doesn’t slide out of control.

I know a couple who had great conflicts in their marriage in one particular area: the husband’s driving. He drove fast. He followed the car in front of him much too closely. He didn’t plan ahead and merged at the last minute. The wife, anxious and nervous about driving anyway, found his aggressive driving style more than she could handle.

Finally one day, the wife told him, “You need to drive for the conditions, and right now the condition is me.” Instead of fuming, holding a grudge, or giving him the silent treatment, she was able to explain what she needed. Because he loves her and wants her comfort, he changed his way of driving.

This couple is my parents, and they will soon celebrate their 50-year anniversary.

Much like considering road conditions, writers consider the rhetorical situation: the writer, the purpose, and the reader. (Justin Jory and Jessie Szalay write more on that here.) In writing, as in driving, writers need to adjust for the conditions, the audience.

Think about what an English 1010 student says about how writing needs to consider the audience and their experience:

This student makes a great point about the writing threshold concept of Context/Contingency: awareness of your audience should determine how you write. Even when writing to an audience that’s knowledgeable about the topic, always err on the side of clarity. In other words, slow down so you make sure your audience is with you.

Here are some tips to write for the conditions.

START SLOWLY WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND THEN BUILD SPEED

When you drive, you start at 0 mph and build up speed. It’s the same with writing. Your writing is not about showing off how much you know by being cryptic and esoteric and leaving your audience to guess what you mean. Considering your rhetorical situation means recognizing your purpose and communicating it in a way your audience can follow. A simple introduction can do wonders to help the audience see the information and why it’s important. You’ve got to ease the reader into your essay. Your audience could have been watching reruns of The Office, buying dog food online, attending yoga class, or any number or random tasks before reading your paper. The point is, your reader, even if they are intensely familiar with your topic, or deeply interested in your progress as a writer, needs a starting place, so take a page out of The Sound of Music, and start at the very beginning.

Most of our public and private discourse comes as a reaction to an event or statement. In other words, writing takes place in the context of what others are saying about events, statements, and research. Graff and Birkenstein explain in their book They Say I Say that having a clear thesis is not enough; it is the writer’s responsibility to show the larger conversation (20). They explain:

When it comes to constructing an argument, we offer you the following advice: remember you are entering a conversation and therefore need to start with “what others are saying . . .” and then introduce your own ideas as a response. Specifically, we suggest that you summarize what “they say” as soon as you can in your text, and remind readers of it at strategic points as your text unfolds. (20–21)

As you write, think about the bigger picture and what “they” may be saying about your issue:

Give your audience enough background so they know what the issue is and why it’s important. At the same time, it’s essential to note that setting the context doesn’t mean overwhelming audiences with pages of explanations that leave the reader unsure of the paper’s purpose. When driving you don’t go 5 mph for the first ten minutes on the freeway just to warm up. Instead, you quickly build up speed so you can merge onto the freeway and get to your destination.

Here’s an example introduction from a paper about the causes of Celiac disease. Notice how it quickly gives context then asks a focusing question to set up the organization for the paper:

This introduction started with the idea that twenty-five years ago most people had no idea what gluten was, moved on to the idea that today you’re sure to have heard of it, and suggested maybe the audience knows someone with Celiac disease or has seen restaurant menus or offerings in the grocery store. Starting from the very basics (most people had no idea) and moving to the question What’s responsible for the increase in Celiac disease? ensures the audience can follow along.

AVOID LENGTHY DETOURS: WEAVE MORE INFORMATION INTO YOUR SENTENCES

Once you’ve used an introduction to orient your reader to the background and importance of your topic, you want to keep them safely with you as you travel together through your paper. You need to make sure the audience has the information they need to follow you. At the same time, keep your purpose clear and narrow. Otherwise, you’ll feel overwhelmed because you know that your audience needs more information, and you’ll feel tempted to give lengthy explanations which risk going off course of your main point.

Our example paper’s purpose is to identify possible causes for the increase in Celiac disease. It can be tempting to give a detailed explanation of the condition, several paragraphs about the symptoms, and even a commentary of how it’s hard to find gluten-free menu options. By this point, the paper might be four pages long and the reader still wouldn’t be sure what the writer’s purpose is.

Because our example paper focuses on only the theorized causes and not the background, definition, or symptoms of the disease, these necessary bits of information can be woven into the sentences using commas, adjectives, and prepositional phrases that add information while still keeping the focus on the causes of Celiac.

Parenthetical Commas

Parenthetical commas, commas that define the term, help writers succinctly add information the reader may need to better understand the subject. See what I did there in the last sentence? I used commas to insert the phrase commas that define the term. Giving definitions and explanations set apart by commas is a simple way to help the reader understand what you’re saying without getting off track. (You can find more discussion about parenthetical commas here.)

Adjectives

Adjectives add description to nouns and are another way to gracefully give more information. Using descriptive words to explain the subject gives readers more context and helps them follow you. In the revised example below, the descriptor herbicide is added to glyphosate to help the reader understand a concept that is probably not common knowledge but can be quickly explained in the sentence.

Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases are used in sentences to modify or give more information about a noun. These phrases start with prepositions (words like of, to, with, around, for, and besides). As you write, consider places in your essay where the reader can use more information to make your writing more clear. (Notice how the underlined phrases in the last sentence could be omitted, but add more clarity to the idea.)

Compare the First Draft and Revised Draft below*, and notice how commas can be used to rename a subject and give more information to the reader and how adding more descriptive words through adjectives and prepositional phrases enhances the meaning.

*Speaking of CONTEXT/CONTINGENCY: This example comes from a Viewpoint Synthesis Paper. In many English 1010 classes here at Salt Lake Community College, students are asked to write a Viewpoint Synthesis paper, an assignment instructing students to research a question and discover multiple viewpoints on the issue. The paper is an exploratory paper—that is, it isn’t making an argument, but rather sharing possible answers to the question. Because of the type of paper, there isn’t an actual thesis statement (thesis statements take a clear position to be argued), but many instructors ask students to compose a “synTHESIS statement,” to appear in the beginning of the essay which summarizes possible answers to the questions posed. The following two draft examples are synTHESIS statements.

First Draft

Not bad, the above paragraph articulately sums up four views on the increase in Celiac disease. But remember, writers consider the context and experience of their audience, who may not have been researching wheat-growing practices for the last four weeks. Simple additions to the sentences can add clarification for the audience while still succinctly identifying causes. Notice the underlined phrases that have been added to the original paragraph:

Revised Draft

In the second example, an adjective phrase giving the definition of wheat breeding, the agricultural practice of crossing different strains of wheat, is added. More information is also given through the prepositional phrase of adding vital wheat gluten and fast acting yeast to recipes, which gives more information about baking processes that could contribute to cause Celiac disease. The addition of the word herbicide, which acts as an adjective, and the explanation the primary ingredient in Roundup weedkiller, set apart by commas, makes a huge difference in how the reader will understand the writing. All of these revisions to the original text allow the reader to more clearly follow the writer’s organization and ideas.

Placing Nouns After the Word This

Placing nouns after the word this is another helpful way to add more clarity for the reader. Many times writers use this, because the thought makes perfect sense in their own mind. We’re all guilty of this oversight (see what I did there?). Because audiences can’t read our minds, err on the side of clarity. Adding a noun after this gives a chance to repeat and redefine concepts.

Do a CTRL+F (or CMD+F on a Mac) search for the word this in your paper. Anytime this appears without a noun, it’s an opportunity to offer more clarification.

Compare:

Adding a noun to this gives a chance to explain more to the reader. Further revision by adding an explanation of Celiac disease in parenthetical commas gives the chance to add even more information the reader may or may not know without having to devote sentences and sentences of explanation. Integrating such information into a sentence makes the explanation sound natural, and helps the reader fit the information together without the writer sounding condescending.

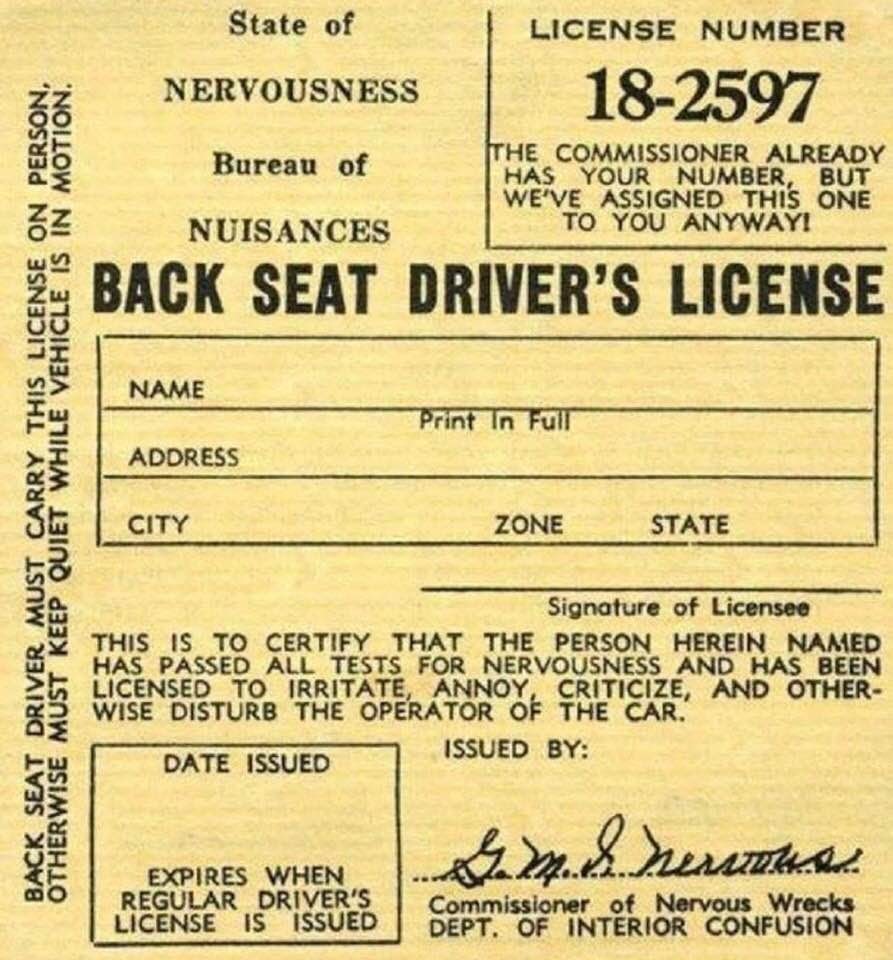

DRIVE SMOOTHLY: USE TRANSITIONS TO LEAD READERS THROUGH THE PAPER

Part of understanding the writing threshold concept of CONTEXT or CONTINGENCY means thinking about how a potential audience will read your writing. Let’s continue our driving metaphor: through an inexplicable chain of events, you are responsible for driving a group of people riding in the back of a flatbed truck, possibly rented from Home Depot. Let me stress that we do not know how you got to this point where this truck was the only available means of transportation, but to further complicate this bewildering metaphorical situation, you are driving on a windy, bumpy dirt road. Luckily, there is a handle attached to the truck that the riders can grab, and avoid plummeting off the truck bed.

The explanations in your sentences are as essential to helping your audience follow your thoughts as providing a handle for the riders to hold on to. But, in the case of the flatbed truck, you’re also going to need to take the bumps and turns cautiously if you want to keep your reader with you. In short, you need to use guiding words and transitions to make sure your reader doesn’t fall off the truck.

Your job as a writer is to lead your reader through your paper. Your paper should have larger organizational markers to keep your reader with you: the introduction, the thesis, and the point sentences that start new sections in the paper and first sentences of other paragraphs in each section of the paper. In addition to the larger organizational markers, you can employ transitional phrases, clear use of old and new information, repetition, and starting paragraphs with the information and not the source as techniques to ensure the “ride” through your paper will be a smooth one.

Transitional Words and Phrases

Transitional words and phrases act as directions to the reader like, “Hold on! Here comes a bump!” or “Watch out for this next turn!” With adequate warning, the reader can hold on and anticipate a change in the road.

In writing, we need to give our readers a chance to “hold on” when a turn or a bump is coming. Use transitional words and phrases to help the reader understand when a new or opposing point will be introduced:

• One view of the issue is _____. Others reject the first view saying _____. Still others say it’s not _____ or _____, but _____.

• Some say it is _____. By contrast, X group says it is _____. A middle ground between the two views is _____.

• At first people saw the issue as _____. As time progressed, the predominant view changed to _____. Now, people see _____.

• Another reason for _____ is _____.

Remember your audience is intelligent but can’t read your mind and needs to be told how it all fits. Your thesis statement will give your audience the “big picture.” Likewise, in a Viewpoint Synthesis paper, your thesis sentence (or really your synTHESIS statement) informs readers about what they can expect to read in your paper. Here’s a variation on the synTHESIS statement we used earlier:

The reader can reasonably expect to first read in the paper about wheat breeding as a cause of Celiac disease and then a discussion of how changes in the bread-baking process are causing more cases of Celiac. Finally, the audience expects to hear about glyphosate.

“Old” and “New” Information

“Old” and “new” information is a concept that says writers should show readers where they’ve been and where they’re going. People are accustomed to building on things they know to help them understand things they aren’t familiar with. In writing, take care to give context to the main idea and orient your reader as to where they are in the paper. When finishing one point and moving on to the next, tell your audience you’re moving from one point in the thesis (or synTHESIS) statement to the next point. You can say things like this:

The words while some and the repetition of the term wheat breeding would remind the reader of the point that had just been made. The words other researchers and the introduction of the claim that there hasn’t been a change in the wheat is a signal to readers that the paper is moving on to the next point forecasted earlier in the paper.

Keeping the reader informed of the movement from old information to new information helps the reader follow exactly where they need to be in your paper. While the concept of “old” and “new” information works in signaling to the reader that one section of the paper is done being discussed and you are ready to move on to the next point, it also works as you move your reader from sentence to sentence.

An example of purposefully using “old” and “new” information is found in the following two paragraphs.

Old Information = Wheat Breeding → New Information = Vital Wheat Gluten

Notice how the concept of researchers is “new” information introduced in the first sentence. In the second sentence, the ideas of researchers is “old” information as the audience learns “new” information: a specific researcher, Kasarda, finds no increase in gluten content but posits that vital wheat gluten might be to blame.

Old Information = Vital Wheat Gluten → New Information = Fast-Acting Yeast

**Stephen Jones was quoted as a source in Philpott’s article. Jones is referenced in the sentences as the authority, but his information came from Philpott’s article, which needs to be cited so the reader can refer to the source (see Works Cited below).

The second paragraph’s first sentence refers to the “old” information the audience knows from the previous paragraph: vital wheat gluten might be a cause. Then, the sentence introduces “new” information that the vital wheat gluten may not be the only modern baking practice to blame. The next sentence builds on the idea that there are other causes and introduces fast-acting yeasts. From here, the “old” information, fast-acting yeasts, is supported by “new” information, Stephen Jones, a source. Jones becomes the “old” information as “new” information becomes Jones has shown sourdough bread … that rises for 12 hours may be more digestible.

These two paragraphs above show how “new” information becomes “old” information to make way for additional “new” information. Each sentence builds upon the next like a highway seamlessly trails behind your car as it moves forward to its destination.

[For more information on sentence fluency or the “known–new contract,” see Nikki Mantyla’s article here.]

Repetition

Repetition shows the audience how the ideas fit not only the big picture (thesis) but also the sections and individual paragraphs in the paper. The idea of how “old” information becomes “new” information wouldn’t work if it weren’t for repeated words. Repetition of key terms such as research, gluten content, and wheat create a continuity of ideas for the audience.

In transition sentences it is especially important to repeat the words or use synonyms for the words found in your thesis. Doing so creates a sense of order about your paper and reminds the reader of their destination.

Starting Paragraphs with the Information, Not the Source

Starting paragraphs with the information, not the source, helps the reader see how each paragraph fits into the overall organization. Often it’s tempting to start a paragraph with the source. After all, you’ve put a lot of time into researching, and you’re familiar with your sources. But talking about the source first without giving the reader context can be confusing for the reader. Remember, while you’ve spent hours and weeks researching your issue and sources, your reader has not. Each sentence and especially the first sentence of each paragraph should lead the reader through the paper.

Compare:

In both examples, the reader had just read about how other causes should be studied. Because readers are accustomed to having new information added to the previous information, the readers naturally wonder what those other causes are. In the first example, the other causes aren’t directly addressed. Instead, the reader is introduced to Tom Philpott, a writer for Mother Jones; a lengthy article title; and Stephen Jones, the wheat breeder. While it’s important to identify sources, doing so at the first of the paragraph throws the audience off its groove. Your Works Cited page will help readers easily identify your source’s article title and publication information; an in-text or parenthetical reference to your source’s last name is sufficient.

The second excerpt, however, continues the thought of other causes of Celiac disease and then introduces sources to better explain those other causes.

CONCLUSION

You might be driving a nervous passenger. Maybe you’re driving a flatbed truck on a bumpy dirt road. Whatever the conditions, make sure your reader stays with you through your paper’s journey. Start slow, gracefully weave more information into your sentences, and use transitions to give your reader the context they need to arrive safely at the destination.

Works Cited

Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. 2012: New York: Norton, 2012.

Jory, Justin and Jessie Szalay. “Why We Might Tell You ‘It Depends’: Insights on the Uncertainties of Writing.” Open English at SLCC Pressbooks. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/why-we-might-tell-you-it-depends-insights-on-the-uncertainties-of-writing/.

Kasarda, Donald D. “Can an Increase in Celiac Disease Be Attributed to an Increase in the Gluten Content of Wheat as a Consequence of Wheat Breeding.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, vol. 61, no. 6, 2013, pp. 1155–1159. EBSCOhost, dx.doi.org.libprox1.slcc.edu:2048/10.1021/jf305122s.

Philpott, Tom. “The Real Problem With Bread (It’s Probably Not Gluten).” Mother Jones, 18 Feb. 2015. www.motherjones.com/environment/2015/02/bread-gluten-rising-yeast-health-problem/.

van Broeck, Hetty C., et al. “Presence of Celiac Disease Epitopes in Modern and Old Hexaploid Wheat Varieties: Wheat Breeding May Have Contributed to Increased Prevalence of Celiac Disease.” Theoretical & Applied Genetics, vol. 121, no. 8, Nov. 2010, pp. 1527–1539. EBSCOhost, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00122-010-1408-4.

Womack, Mark. “Parenthetical Commas.” drmarkwomack.com/a-writing-handbook/punctuation/commas/parenthetical-commas/.