11 Rhetorical Appeals, Components & Devices

In this chapter, students will practice:

- thinking about how texts appeal to and affect specific audiences

- identifying specific multimodal text elements and how they make appeals

- recognizing rhetorical devices speakers leverage through text components

- thinking about how components, appeals, and devices are layered and work together to evoke response

Rhetorical appeals

If the rhetorical situation refers to what texts are part of and text elements refers to what texts are made of, then rhetorical appeals are what the text is composed to do and how the author intends the text to work. Rhetorical appeals are the qualities of an argument that make it persuasive or the qualities of communication that, in some way, move audiences.

Aristotle came up with three ways rhetorical appeals work. He taught that a speaker’s ability to persuade an audience is based on how well the speaker appeals to that audience in three different areas: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Ethos: appeal to credibility and character

Ethos is the appeal focused on the writer. It refers to the character of the writer, including her credibility and trustworthiness. Credibility refers to speaker’s knowledge and expertise in the subject at hand. Character is who a person is based on their history, experiences, choices, personality, and values. Appealing to ethos changes depending on the rhetorical situation, the audience addressed, and the genre the author is writing in. For example, for lab reports and academic publication, the reader must be convinced that the author is an expert, is knowledgeable in their field, is a trustworthy researcher, and that their work merits attention. Alternatively, for a politician, constituents must be convinced their representative has intentions that align with their, that they can trust them with to understand and act on behalf of their needs and desires, and is capable of leadership and negotiation amongst other politicians.

On the one hand, when an author makes an ethical appeal, they are attempting to tap into the values or ideologies that the audience holds. Examples include patriotism, tradition, justice, equality, dignity for all humankind, self-preservation, or other specific social, religious or philosophical values (Christian values, socialism, capitalism, feminism, etc.). These values can sometimes feel very close to emotions and therefore also work as pathos. Speakers use values to identify themselves as ethical or trustworthy and also use values to tap into their audiences’ passionate beliefs.

Ethos is present in text’s in texts in two ways. First, through the author’s certification, reputation, or experience—in other words, who they are known to be in the world. For example, readers are more likely to trust health advice from a medical doctor than a carpenter and should listen to a carpenter about their house frame before they listen to medical doctor. In court, juries are more likely to trust testimony from an eyewitness than someone who heard about a crime from a friend. This kind of ethos is communicated through information the writer offers about themselves in their text or byline or can be found through research. Famous speakers have an ethos they’ve built through an accumulation of texts, interviews, appearances, etc. that they rely on for credibility and authority. Second, through the author’s creation or representation of themselves in the text. Speakers create ethos through their text component choices like voice, point of view, diction, grammar, style, information, description, etc.

Pathos: appeal to emotion

Pathos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the reader. Pathos refers to the emotions that are stirred in the reader while reading the manuscript. The author should seek to trigger specific emotional reactions in their writing. An author using pathos appeals wants the audience to feel something: anger, pride, joy, rage, happiness, superiority, inferiority, fear, worry, embarrassed, annoyance, anger, etc. For example, many of us have seen the ASPCA commercials that use photographs of injured puppies, or sad-looking kittens, and slow, depressing music to emotionally persuade their audience to donate money. This is a classic example of the use of pathos in argument.

Pathos-based rhetorical strategies are any strategies that get the audience to “open up” to the topic, the argument, or to the author through an emotional connection. Emotions can make us vulnerable and an author can use this vulnerability to get the audience to believe that their argument is a compelling one.

Pathos appeals might include:

- Expressive descriptions of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel or experience those events

- Vivid imagery of people, places or events that help the reader to feel like they are seeing those events

- Sharing personal stories that make the reader feel a connection to, or empathy for, the person being described

- Using emotion-laden vocabulary as a way to put the reader into that specific emotional mindset (what is the author trying to make the audience feel? and how are they doing that?)

- Using any information that will evoke an emotional response from the audience. This could involve making the audience feel empathy or disgust for the person/group/event being discussed, or perhaps connection to or rejection of the person/group/event being discussed.

Logos: appeal to logic

Logos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the argument or reason(s) being presented by the author. It is an appeal to rationality, referring to the clarity and logical integrity of the argument. Logos is, therefore, primarily rooted in the reasoning that holds different elements of the manuscript’s argument together. Do the findings logically connect to support the conclusion being drawn? Does the evidence support the author’s claim? Does the speaker’s argument make sense?

When an author relies on logos, it means that they are using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. Objective evidence is anything that can be proven with statistics or other facts via more than one source. Oftentimes that evidence has been validated by more than one authority in the field of study.

Remember, that what counts as “evidence” and “logic” is different across different communities and across topics. A group of scientists is going to consider peer-reviewed experiment-based findings adequate evidence; they are probably not going to consider a memoir adequate evidence. Humanities scholars are going to consider archival documents and primary accounts adequate evidence. YouTube videos or social media posts might work as evidence for some claims but not others. Religious texts, similarly, are going to resonate with particular audiences and particular arguments and not others. This is one reason modern discourse is so complicated: what seems completely reasonable to one group of people is nonsensical to another and the media makes little effort to account for worldviews.

Logical appeals rest on rational modes of thinking, such as:

- Comparison: a comparison between one thing (with regard to your topic) and another, similar thing to help support your claim. It is important that the comparison is fair and valid – the things being compared must share significant traits of similarity.

- Cause/effect thinking: you argue that X has caused Y, or that X is likely to cause Y to help support your claim. Be careful with the latter – it can be difficult to predict that something “will” happen in the future.

- Deductive reasoning: starting with a broad, general claim/example and using it to support a more specific point or claim (picture an hourglass where the sands gather in the middle)

- Inductive reasoning: using several specific examples or cases to make a broad generalization (consider the old question of “if your friend jumped off of a bridge, would you” to make the sweeping claim that all young people are easily persuaded to follow the crowd)

- Analogical reasoning: moves from one particular claim/example to another, seemingly sequential (sometimes this line of reasoning is used to make a guilt by association claim)

- Exemplification: use of many examples or a variety of evidence to support a single point

- Elaboration: moving beyond just including a fact, but explaining the significance or relevance of that fact

- Coherent thought: maintaining a well-organized line of reasoning; not repeating ideas or jumping around

Finally, it is important to remember that ethos, logos, and pathos are not distinct, independent categories. They influence each other, they work together, and text components often make more than one kind of appeal. For example, if someone is arguing for better funding for child care services in Texas and they offer a story about being a single parent in Dallas, their narrative appeals to ethos by establishing their credibility and character through their personal experience, appeals to the audience’s emotions by describing their child and their hardship, and appeals to logic by offering eyewitness evidence that the current system is failing.

Rhetorical affects

“Affect” refers to how audience(s) respond, unconsciously and consciously, to a text. It can be helpful to consider affect as responses to particular appeals:

- Ethos: What does the audience now think about the speaker’s credibility and character? Do they trust the speaker? Do they like them? Do they identify with them?

- Pathos: What did the audience feel while experiencing the text and what do they feel after exposure to it? Were their senses triggered? Were they reminded of particular experiences they have had?

- Logos: Does the audience understand why the author thinks the way they think? Do they think they were given sufficient, quality evidence? Do they get the primary claim? Do they feel like the piece is logical?

Remember, different audiences are going to respond differently to the same texts depending on their values, beliefs, experiences, education, perspectives, investments, needs, and desires. You can do research to predict or even prove how audience’s respond to particular kinds of texts. We now, for better and for worse, have access to affect and response through: comments sections, TikTok videos, online reviews, posts or tweets, editorials. You can also interview people in your class or your community to discover their response. Finally, don’t forget that YOU are a member of the audience. How the text affected you tells you something about it.

Practice: Rhetorical Précis

A rhetorical précis (pronounced pray-see) differs from a summary in that it is a less neutral, more analytical condensation of both the content and method of the original text. If you think of a summary as primarily a brief representation of what a text says, then you might think of the rhetorical précis as a brief representation of what a text both says and does. Although less common than a summary, a rhetorical précis is a particularly useful way to sum up your understanding of how a text works rhetorically.

The rhetorical précis assignment helps you to summarize a ten to twenty-five page article into five succinct, concise sentences which will allow you to remember the important points of the article. Writing a precis, a shorter version of an article annotation, for everything you read in all of your college classes will also help you keep track of valuable information, organize articles and other sources for your research papers, and help you build your own set of resources for your classes and future career. Writing précis can be an excellent study skill, particularly for essay exams that allow you to bring your own notes, or just to help you weed out the less important information and hone in on the things you really need to learn.

THE STRUCTURE OF A RHETORICAL PRÉCIS:

Sentence One: Name of author, genre, and title of work, date in parentheses; a rhetorically active verb; and a THAT clause containing the major assertion or thesis in the text.

Sentence Two: An explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis.

Sentence Three: A statement of the author’s apparent purpose, followed by an “in order to” phrase.

Sentence Four: A description of the intended audience and/or the relationship the author establishes with the audience.

Sentence Five: An analysis of the significance or importance of this work.

Time to Practice:

Read this essay: “Writing as Reckoning”

Read the essay once and try to find the thesis statement, author’s purpose, audience, and why the author feels this work is important or significant to the field of study. Practice writing out a precis.

Examining text components

In the previous chapter, we talked about how texts are made of manifold components and how different media forms influence the kinds of components speakers (can) use. “Components” refers to all the pieces of which a text is made—everything from individual letter shapes to punctuation to sentence structure to imagery and diction to paragraph breaks and chapter organization to colors and photographs to sound and lighting depending on the media form. In this chapter, we’re going to begin to break down and out these components that, individually and collectively, make meaning, make messages, make appeals, and engender affects. Remember, a text is made of thousands of choices the speaker had and the decisions and selections they, consciously or unconsciously, made. Remember, too, that medium and genre are always at play, delimiting the choices speakers can make if they want to be legible and recognizable to particular communities and audiences.

We can feel overwhelmed when we start thinking about all the things of which a text is made and all the things from which we can make a text. You can break down text components in the following ways in order to see and think about your work and the work of others more clearly:

- Content: What claims, information, and evidence did the speaker choose to include to reach their audience? What information or evidence did they choose NOT to include? This is the topic of the next chapter.

- Style and form: What kinds of words, media, colors, tone, images, description, syntax, grammar, and formats did the writer choose to engender particular appeals and affects? What rhetorical devices did the speaker choose to leverage? What decisions have they made regarding genre?

- Arrangement: How has the speaker put their content together to align with their purpose? In what order is it presented to their reader and why? What content have they made more important or less important via placement, proximity, font size, etc.?

Text components across media forms

Text components look different across different media forms. You are still thinking about content, arrangement, and style, but you have to be able to see these pieces across diverse texts. The following chart is intended to help you start seeing components across media.

Speech |

Written |

Image |

Film |

| Examples: presentations, public addresses, radio shows, podcasts, conversations, interviews, | Examples: articles, books, tweets/posts, blogs, comments sections, journals, textbooks, reports, editorials, newspapers | Examples: photographs, illustrations, paintings, cartoons, charts, graphs, Instagram, data visualization, sculpture, | Examples: commercials, movies, news broadcasts, TV shows, TikTok, YouTube, |

| Components: Words, statements, sounds, voice intonations, diction, descriptions, questions, repetition, rhythm, colloquialisms, slang, sensory language, tone, jargon, syllable stress, syllable articulation, accent, language, loudness, softness, sound effects, white noise, background noise, music, vocal tics or fillers, pauses, silences, hand gestures, body movements, laughter, snorts, throat clearing, etc. | Components: letters, punctuation, grammar, diction, language, perspective, tone, word choice, rhythm, sensory language, paragraph breaks, headers, footers, margins, columns, typeface, fonts, letter spacing, line spacing, negative space, order, visual hierarchy, headline, title, byline, subtitles, lists, narrative, exposition, facts, data, statistics, claims, testimony, dialogue, introductions, conclusions, document length, letter size, word count, etc. | Components: color, contrast, hue, brightness, saturation, line thickness, shapes, frame, representation, subjects, angle, perspective, objects, vanishing point, horizon, blur, transparency, resolution, quality, caption, title, labels, size, composition, negative space, visual hierarchy, layout, foreground, background, focus, shadows, light, etc. | Components: panning, zoom, frame, angle, perspective, color, contrast, hue, brightness, saturation, shapes, frame, representation, subjects, objects, vanishing point, horizon, blur, transparency, resolution, quality, caption, title, size, composition, negative space, visual hierarchy, layout, foreground, background, focus, shadows, light, sound effects, white noise, background noise, music, silence, gestures, movement, etc. |

Remember, most media today is, in fact, mixed media. For example, print newspaper articles are primarily written but they also often contain image elements like photographs or charts. News websites, meanwhile, contain multiple layers of writing, images, sounds, and videos. How do these shifts in media and format impact the viewer? Do you think media form changes the way audiences read the news? The ways they respond to it? The way they interpret it? How do you think demographics like age impact which form audiences choose? How do demographics like class shift who has access to print or digital subscriptions and who, therefore, has access to certain types of news?

Considering the multimodality of media

The modality of communication refers to the basic sensory means by which communication happens. All of the above media components reach audiences differently and influence them differently. Thinking about multimodality helps us think about how different text components are designed to appeal and how they actually affect.

- The verbal modality refers to words spoken or sung or typed or handwritten on a piece of paper or screen.

- The visual modality refers to live images, still images, or images moving on a screen

- The auditory modality refers to spoken words, sung words, sounds, music tracks, laugh tracks, and noise

- The haptic modality refers to touch and what we can feel with our hands and skin like keyboards, screens, paper, packaging, clothing, etc.

If you think about it, ALL forms of communication involve multiple modalities. Jodie Nicotra points out in Becoming Rhetorical that:

“A speech, for instance, includes the verbal modality (spoken words), the auditory modality (the pitch and tone of a speaker’s voice), and visual modalities (the speaker’s appearance, gestures, facial expressions, and perhaps slides). Video games use haptic, auditory, and visual modalities. Even reading the printed page encompasses verbal (words), visual (typefaces, formatting, punctuation, etc.), auditory (page turns), and haptic (the feel of paper, of book binding) modalities.”

Understanding these layers helps us understand speakers,’ and our own, appeal and affects.

Discussion: Visual Rhetoric

What is visual rhetoric? To briefly answer this question, let’s first unpack these two terms. Rhetoric, as we defined earlier in this unit, is the art of persuasion; we use it every day to communicate in ways aimed at convincing other people to go along with our ideas (or at least to consider them). By “visual,” we mean “the cultural practices of seeing and looking, as well as the artifacts produced in diverse communicative forms and mediums” (Olsen et al, p. 3). In other words, “visual” refers not just to what we see (“artifacts” such as cartoons, memes, movies, photographs, posters, fonts, symbols, icons, and colors), but how we see (for example, we may or may not associate red-white-and-blue with the U.S. flag and patriotism, depending on our cultural background and beliefs). By visual rhetoric, then, we mean the many ways imagery is used to communicate, create meaning, and compel us to think, feel, know, and act.

Let’s carry this thought a little further. In the study of visual rhetoric, we acknowledge that “images have power” (Sheffield), and we ask, “How do images act rhetorically upon viewers?” (Helmers and Hill 1). We explore the influence that visuals have on us and our audiences, and we recognize that visuals produce rhetorical effects; they use ethos, logos, and pathos appeals to influence an audience.

Visual rhetoric scholars Helmers and Hill, for example, mention a wide variety of examples: cave art, Egyptian hieroglyphics, stained-glass windows in churches, World War II posters, editorial cartoons, motion pictures, charts, graphs, and so much more. They point out the power or influence of some of these visuals, like Thomas E. Franklin’s 2001 photo, Firefighters at Ground Zero, taken the day after the World Trade Center collapsed. The photo shows firefighters raising a fallen flag on the rubble-strewn site. Helmers and Hill point out how such visuals communicate to us culturally and intertextually; that is, Franklin’s photo reminded some viewers of a now-iconic photograph and sculpture of the U.S. Marines raising the flag on Iwo Jima during World War II; even if some viewers did not “get” the reference, the centrality of the flag in the photo and the firefighters’ upward gaze communicated what the photographer called “the strength of the American people” (7). That emotional effect, Helmers and Hill explain, was reinforced by widespread distribution of the photo by news media as well as its cultural context (i.e., how many viewers connected it to the war-time, Iwo Jima photo).

Of course, visual rhetorics draw our attention to more than emotional responses and cultural contexts. In “Breaking Down an Image,” for example, Jenna Pack Sheffield outlines how such elements as fonts, arrangement, colors, and more relate to purpose, audience, and context—the rhetorical situation, in other words. To illustrate, Sheffield displays an advertisement for a men’s watch:

She points out such key visual elements as the arrangement, color, fonts, and scale of images and text in relation to one another. The ad displays a close-up view of the watch in the bottom-right corner, the brand label in the upper-right corner, and, in the background, the blurred image of a man running. Look closely, and you can see the faint outline of a watch on his wrist. Each detail creates meaning and in some way creates an overall impression while also supporting the ultimate purpose (to sell a watch). For example, Sheffield says of the font choice in the company logo:

A “silly or playful font” might be more suitable for a kid’s watch, but such a choice would not support the overall purpose of the ad, its likely adult audience, or the ethos (character) of the company (or at least, the character it is trying to convey by choosing a strong, bolded, ALL-CAPS font); nor would it support the intended pathos (the “strong, serious, font type,” which Sheffield points out, playfully).

Why pay attention to details in visual artifacts? Sheffield explains that by noticing each element and understanding its possible individual and combined effects on the target audience, we can “break down” a visual. That is, we can analyze it. In the next chapter, we will discuss analysis, which aims to describe the content of an artifact, identify its key parts, and evaluate it. If we were analyzing the Pro Trek ad for a writing assignment, for example, we would work our way through these steps. We would also ultimately ask critical or evaluative questions such as: What details draw our attention first, and why do we think that is so? Sheffield mentions that in Western cultures, we read left to right, top to bottom; therefore, the order or arrangement of elements makes a significant difference to how we interpret an image.

Other questions we might ask include:

- Does the chosen font communicate something important to the overall purpose?

- What overall effect or effects do the colors create?

- Is it significant that the man’s image is blurred while both the logo and the watch itself are in focus?

- Overall, is the ad effective, and what evidence supports our assessment?

These questions are just a few critical or analytical explorations we might consider. For a full analysis of the ad, we would also likely consider what we know about the company, its products, and its customers. What is the company ethos or character?

By breaking down or analyzing the advertisement in such ways, we move toward synthesis. That is, we start making connections between the visual details, showing how they relate to each other and how they make the advertiser’s case (or not).

Analyzing Multimodal Compositions

- First, identify the rhetorical situation (speaker, audience, purpose, setting, text of the piece as well as its medium, genre, and circulation). Remember, there may be more than one intended audience especially in digital spaces where speakers have to address their followers or consumers and also businesses who might want to post ads on their website.

- Then identify the modalities present in the piece, thinking about the rhetorical appeals and affects of each. How do the various multimodal components contribute to this effect? Jodie Nicotra, in Becoming Rhetorical, guides us to ask:

- Does it use spoken or written language? Where and why is language used? What tone do the words create? What rhetorical devices do you notice?

- Does it use still or static images? How are these images arranged?

- Does it use moving images? What sequence do these images follow and why? How are they edited?

- Does it use sound? What kinds: interviews, narration, music without words, music with words, other kinds of sounds? How would you characterize these sounds? How are they layered and edited?

- How do users physically interact with the text? Do they turn pages, do they listen while walking or driving, do they click links, touch a screen use controllers?

- Finally, consider the multimodal composition as a whole: How do the pieces work together to create an overall effect? What do they DO?

It might help you to create a chart or matrix where you can pull out and name the text’s different components and think about what they do individually and together. Below is a model of this method:

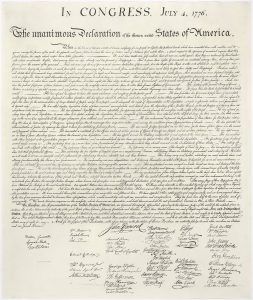

The text:

The chart:

| Text component | What do you notice about it? | How do you think it affects or appeals to the audience? | What do you think it accomplishes for the speaker/purpose? | Is there another component it is working closely with? |

| Heading | “In CONGRESS, July 4, 1776, The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America. “ | following formal genre of decrees and documents of law | signals importance, references and assumes authority of the genre and those who are allowed to use it | |

| Signatures | 56 different names and different handwriting, all men, | |||

| Parchment paper | The Declaration of Independence was written on parchment because it was considered a more durable and formal writing surface than paper at the time. made from treated animal skin, was known for its longevity and ability to withstand handling, making it suitable for important documents

|

parchment was associated with official and prestigious documents, lending an air of authority to the Declaration | working with heading and other genre/medium elements expected of official documents of the time | |

| “We the people” | Acting subject of first sentence and declaration writ large | Stark contrast to singular authority of the king of England. | establish collective will as foundation for representative democracy. Establish a different and new kind of authority predicated on Western Enlightenment philosophy | |

| Different “fonts” | document is handwritten but the script changes. “CONGRESS” is in all caps. the numbers in the date are slanted, the title is written in a fancier, larger, bolder, print script with longer serifs while the body of the document is written in thin cursive |

Practice: Recipe Blogs

Recipe blogs are a persuasive multimodal genre. As a class, gather three to five examples and analyze each using the steps listed above.

Then generate a list of criteria that you might use to evaluate the form of communication. What components makes a recipe blog a recipe blog? Which components do you think are most important for reaching/persuading different audiences?

Recognizing rhetorical devices

A rhetorical device is typically defined as a technique or word construction that a speaker or writer uses to win an audience to their side, either while trying to persuade them to do something or trying to win an argument. Many of the terms we use to refer to rhetorical devices are in Greek because they were articulated by classical philosophers like Aristotle. There are dozens of rhetorical devices, which you can find on a handout here. Below are five common rhetorical devices, so you can start thinking about how they work.

- anaphora: Repetition of a word or expression at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect.

- Ex. we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground

- antiphrasis: The usually ironic or humorous use of words in senses opposite to the generally accepted meanings.

- Ex. this giant of 3 feet 4 inches

- epistrophe: Repetition of a word or expression at the end of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect.

- Ex. of the people, by the people, for the people

- hyperbole: Extravagant exaggeration.

- Ex. mile-high ice-cream cones

- litotes: the affirmation of something by negating the opposite.

- Ex. It’s not rocket science

Please note that some of these devices are also known as literary devices. That means they are primarily instruments of narrative. Since rhetoric deploys narrative, you can find literary devices in arguments and across other forms of communication. You can also check out this video on “Common Rhetorical Devices.”