Introduction to First Year Composition

Welcome to Reading and Writing in College, an open-source textbook designed to support the work of undergraduate writers enrolled in composition courses! Although many of the topics addressed in these digital pages are written with first- and second-year students in mind, the content remains relevant for writers at any stage of writerly development.

You can navigate through this book in any way you choose. Feel free to read straight through—from Chapter One to Chapter Twelve—or jump around. Much of the information provided doesn’t build on knowledge from previous chapters, although occasionally you’ll want to head back to the table of contents if you feel like you need additional reading or support in understanding a particular concept. For citation information on copyrighted content, please visit our Works Cited page; attribution for Creative Commons licensed material can be found at the bottom of each individual page.

Writing in College

Motivated by Inquiry

When we write with a question in mind—even if the question is not apparent to us yet—we engage in inquiry. According to The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, inquiry can be defined as:

1: a request for information

2: a systematic investigation often of a manner of public interest

3: examination into facts or principles: RESEARCH.

If we trace the roots of inquiry back to its Latin origin, we encounter the word inquirere, which simply means “to seek” (Merriam-Webster Online). Through the act of writing, we seek answers to burning social questions, such as “Why do people self-sabotage their most important relationships?” or “What do dreams tell us about the human mind?” We may also seek answers to practical questions we find ourselves asking in simple, everyday moments. For example, “What’s the most sought after skill employers look for when hiring recently graduated college students?” or “Why do my best ideas occur while I’m daydreaming in the shower?”

Understood as a Process

It’s not uncommon for college students to tell their writing instructors all about the red ink they’ve seen on the drafts of papers that were returned to them. Equally common is to hear from students that their high school English teachers simply didn’t have time to write many comments on student papers or return papers to students at all. When the paper was submitted, it was a finished product. No further revision necessary. This practice is problematic because it doesn’t teach student writers what professional writers do every day, which is to engage with writing as an ongoing process. Professional writers tend to produce many drafts and work across drafts, going back frequently to retool or overhaul whole sections of their drafts prior to submitting their work to editors for multiple copyediting and proofing passes before going to press. Even after publication, professional writers know their work on a piece is never finished. Sometimes retractions and corrections need to be issued after a piece has been published. Or as is often the case in book publishing, newer editions of a text are created based on suggested revisions or new insights. A writer’s work is never done because good writing requires the writer to adopt a recursive writing process.

College writing instructors also tend to value process over product, which means that your process as a writer doesn’t necessarily end after a particular draft is submitted for grading. On the contrary, you might think more expansively in terms of your process as a writer by reflecting on how you typically begin brainstorming, how you move through stages of drafting, receive feedback from peers or your instructor, revise according to that feedback, and then return for additional revisions as your thinking on the piece develops. In other words, just because you may be finished writing one draft does not mean that your work as a writer is complete. We are best served when we think about how our ideas transcend the page, moving across drafts and sometimes even across assignments to strengthen how we communicate with a broad audience of readers.

Situated in Context & Community

Moreover, college-level writing courses often offer a sense of being in community with other writers. American literary theorist Kenneth Burke is frequently cited for his description of academic writing as entering a kind of parlor or a room in which people are gathering and a lively conversation is underway. Burke writes,

You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress. (110-111)

Whether you realize it or not, when you write your ideas are always informed by the ideas of those who came before you. Your writing is part of a larger, ongoing community that has been in conversation with other interested community members for quite some time now, and this community should give you a sense of audience, purpose, and context. Similarly, peer review is a staple practice in college writing courses. Your instructor is very likely to ask you to trade drafts with another student writer to provide constructive feedback that will help to improve your writing and give you a sense of community that functions as an audience as well.

Multimodal

Translingual

By considering some of the major differences between high school and college-level writing in this chapter, we have allowed ourselves to percolate on the purpose of writing practice that differs from one educational institution to another. We’ve also thought about how the audience for writing changes across these different educational contexts. In high school, the purpose of learning to write is often determined by the school district’s emphasis on achievement in standardized testing scenarios or rigid, state-mandated curricula that leaves little room for organic, creative exploration of writing as a process or of research as a way of coming to find new and unexpected answers. To those ends, the immediate audience is the teacher or the entities that determine what good writing looks like, which in turn creates a context for writing that can be firm and defined, like a limited menu.

College writing, on the other hand, resists such definition. In college, your purpose is to practice writing in a way that invites you to ponder and to push back on the standardized expectations of what writing should look like because there is more than one way to write well. At the same time, you have a professional audience of readers—your classmates, your instructor, and a broader audience of potential readers with whom you might share your writing—who yearn to read a piece composed with feeling, one that is stylish, well-formatted, easy to read but also backed by credible research. These expectations shift based on the context within which we write, of course, so that when major political, social, or global events come to bear on our lives, we find ways to address the new conditions in which we live and work. Writing in college is very much about waking up to the world around you and writing in a way that responds to that world. Much like the restaurant metaphor at the start of this chapter, when writing for a college audience, you should enter and leave a piece feeling like you’ve partaken in a memorable, satisfying experience. You should look around and notice all the care that goes into such a sensory, well-presented experience. Enjoy the sights and sounds that your words can produce. You have arrived. Grab a fork and dive in.

Application: Your Writing Inventory (table)

At the beginning of the semester, it can be helpful to you to take inventory of your past writing experiences and to reflect on how these experiences inform who you are as a writer today. To that end, write a letter to your teacher that answers the following reflection questions:

- How many years of English did you take in high school and/or what types of English classes did you most enjoy? Why did you enjoy these most?

- Which English classes did you enjoy the least? Why did you enjoy these the least?

- What were the 1-2 most important lessons you learned about writing through your high school coursework?

- What genres or types of writing assignments do you remember being assigned? Or what writing-related activities did you complete in or out of class?

- How do you write in your day-to-day life? What genres or types of writing do you engage in most often (i.e., class-assigned writing projects, texting, social media, email)? What genres or types of text do you read most often? Why?

- Lastly, what genres or types of writing will be most useful to you as a student in college and (eventually) a professional in your future career?

Introduction to Multimodality

A multimodal composition will:

- Use two or more of the five primary communication modes (aural, gestural, linguistic, spatial, and visual).

- Understand how media differ from the communication modes.

First, what is multimodality? Multimodality refers to the five primary modes or ways by which we communicate: aural, gestural, linguistic, spatial, and visual. Think of it this way: If you were composing a message on a social-media platform like Twitter or Instagram, instead of “relying only on alphabetic letters, [you would] include voice messages, images, photographs, music, emoticons, web links, and other . . . multimodal elements to make [your] points” (Ball and Loewe 311). The reference to “alphabetic letters” refers to linguistic communication modes, while the other options draw primarily on visual and aural modes. The key point here is that you would very likely use several communication modes in your post, not just because you can on those platforms but because the combination suits your audience, purpose, and context (i.e., the rhetorical situation).

All communication is multimodal. In this textbook, for example, we communicate with you via words on a page or screen; our modes are linguistic and visual. On the other hand, you may be listening to these words, which we would describe as an aural-linguistic mode. Most communication also includes spatial modes that communicate meaning: On the page or screen, for example, letters are grouped together as words, with space between them; paragraphs are separated in ways that enhance communication, too, along with section headers and titles. In face-to-face interactions or on Zoom, we would speak these words aloud but also add gestures that communicate additional information or cues; such an interaction combines aural, linguistic, and gestural modes.

Multimodality an important skill for your genre toolbox. By choosing the mode(s) best suited to your rhetorical situation, you improve your chances of communicating persuasively and effectively. Being able to choose and mix modes makes you a more skillful communicator. In the advertisement genre, for example, you may be familiar with television ads calling on you, the viewer, to help save abandoned or abused animals. What kind of music typically accompanies the visual and alphabetic elements of such an ad? Sad music. Would these ads work if the music was happy and upbeat? Remember that we have expectations about genres; we expect the music and images in such an ad to evoke sad emotions. In these ads, sound/music, images, and words work together to communicate a message.

Modes and media are different but related concepts. A medium is a singular material or interface through which we communicate a message or messages. Examples of media (the plural of medium) include newspapers, paintings, social-media apps, Zoom, or even your course learning management system. In a sense, media are the materials that lie between the communicator and the communication. A mode, on the other hand, refers to the channels or resources through which media are sent. For example, have you ever seen words or images etched in chalk on a sidewalk? The sidewalk and the chalk are the media; the words and images used communicate the creator’s message through the visual and linguistic modes. In the case of this textbook, the medium is the computer screen; the mode is visual and linguistic (and possibly aural, if you’re using a screen reader or reading aloud).

What’s it like to consider the modes of your composition? Elsewhere in this chapter, we discuss genres that, when considered as written compositions, employ at least two modes (visual and linguistic). Other multimodal possibilities for getting your points across include infographics, photographs, charts and diagrams, slideshows, presentations, podcasts, animation, videos, and so much more. You can use these multimodal genres to supplement your written, “alphacentric” essays, or expand them into new compositions on their own.

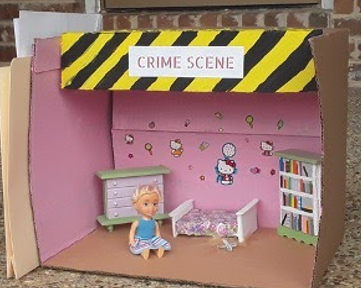

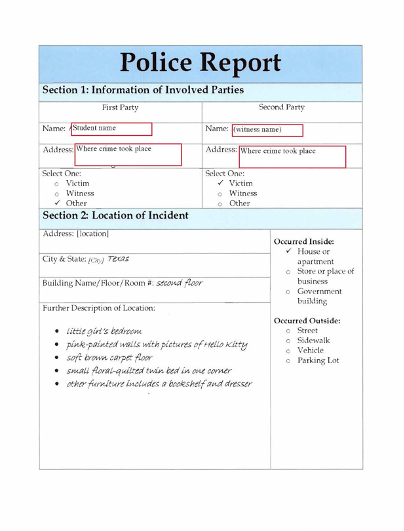

For example, in “The Scissors Incident,” a crafted project featured in the 2020-2021 FYC eReader, the student multimodality transformed a narrative written earlier in the semester. For a remix project later in the course, she pondered ways to present her project in more than two modes. One aspect of the resulting project was a diorama she made of a “crime scene.” What three modes can you identify in a photograph of her project?

When the student presented this project, she used the premise that her “audience” of classmates were investigators attending a “crime” update. First, she provided her audience with a police report documenting the crime, then she talked to them as if she were the chief investigator. Her presentation was aural, linguistic, visual, spatial, and gestural. The diorama is visual, linguistic, and spatial in its use of modes, and so were the handouts. The entire project exemplifies multimodal composing as a practice, a skill you use every time you communicate.

Let’s review. First, modes are the primary ways we communicate—aural, visual, linguistic, spatial, and gestural. Second, all communication is multimodal; that is, all communication combines at least two modes in order to deliver or create meaning. Third, by understanding the modes best suited to your audience, purpose, and situation, you can communicate persuasively and effectively. These factors are why multimodal composing is such a valuable skill to employ across genres.

In the next section, we’ll discuss the typical writing genres you might encounter in a first-year writing classroom or in your college writing experience. While these genres are not the only genres you might encounter, they do capture the range of writing styles that you might need. In each section, we’ll provide a description of the genre, audience expectations, genre significance, and examples.

What are some examples of this genre?