10 Rhetoric & Rhetorical Analysis

In this chapter, we will practice:

- understanding what rhetoric and rhetorical analysis are

- researching and identifying texts’ rhetorical situations

- thinking about appeals and how speakers make them via text elements

- identifying persuasive claims and arguments texts make

- thinking about how texts affect specific audiences and situations

What is rhetoric?

In the world, rhetoric refers to the power of language, signs, and symbols to move/affect bodies. It refers to the ways people argue. It refers to the ways we are persuaded. We tend to use the word “rhetoric” in a negative way to refer to messages intended to manipulate or “trick” us. But actually all communication is rhetorical. All communication is composed to forward a message and evoke a response. Rhetoric is a thing we are doing all the time. In school, “rhetoric” refers to the study of the power of language, signs, and symbols to move/affect bodies. It refers to understanding how language, signs, and symbols are (consciously and unconsciously) used by speakers to communicate certain particular meanings and how audiences (consciously and unconsciously) respond. Rhetoric is how communication happens, how communication works. Rhetoric asks: What does this text DO? What does language DO?

Because writing and communication is embedded in community and context, we must also be rhetorical, as in responsive to specific audiences’ needs and expectations, considering of specific contexts, and composed towards specific purpose in relation to context and audience. In this unit, we will learn to think critically and think strategically about our own and others’ rhetoric. We will also learn how to write analytically about rhetoric.

Before we begin, however, we must remember one key factor of this unit and this course: you are already doing rhetoric all the time. You are already a savvy speaker. You are already a savvy audience member. Every time you determine whether an email is spam or an image AI-generated, you are doing rhetoric. Every time you write a resumé or a college-entrance essay or go to a job interview, you are doing rhetoric. Every time you argue with your siblings or convince your friends to see a movie, you are doing rhetoric. Our goal is to help you sharpen your skills, to deploy them consciously towards your own ends, to give you language to understand distinctions between communication and manipulation, and to realize the power you daily wield.

Discussion: Rhetoric & Culture

The study of rhetoric is often credited to Western philosophers like Gorgias, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle and many of the terms we use use in rhetoric today come from these ancient speakers. But rhetoric does not belong to one particular culture, but instead has a rich history featuring different styles and approaches to the art of persuasion across the globe. Rather than thinking that one persuasive method is “right” and another is “wrong,” we need to recognize that persuasion depends on context, which involves cultural, historical, technological, and situational factors that determine successful arguments. Furthermore, the persuasive tools available to us today are very different from those used even in recent history. Think of the ways that social media has expanded our understanding of and connection other people living around the globe. The possible means of persuasion have expanded throughout history, which means that writers need to determine which tools can possibly help them in an argument.

We can point to many examples of rhetoric around the world that may help us see beyond the classical Greco-Roman concepts. In Ancient Egypt, for example, silence was a powerful rhetorical tool. Silence was not only an indicator of good character (or ethos, as the Greeks would say), but also aligned the person who declined to speak too much with the order inherent in the universe itself. To be wisely quiet instead of foolishly gabby was to invite the presence of the goddess Ma’at, whose truth and order would work on one’s behalf (David Hutto’s work develops this in some detail).

Consider, also, a major moment in the organization of rhetoric in China: Chen Kui’s work Wen Ze (or The Rules of Writing) from 1170 CE. Kirkpatrick and Xu tell us a bit about Kui’s major contributions:

The rhetorical principles that The Rules of Writing promulgates include the importance of using clear and straightforward language, the primacy of meaning over form, and ways of arranging argument. These principles were, in large part, determined by the needs of the time… because The Rules of Writing was written at a time of great change in China. Two changes were of particular importance.

The first of China’s major changes was the advent of printing, which “made texts much more accessible and affordable than they had been before” (5). China’s second major societal change was the increasing number of people working for the government. As Kirkpatrick and Xu tell us, China’s hiring practices during this time shifted, which meant that people entered these civil service jobs through their own merit instead through inheritance or by privilege alone, which meant they needed to really have rhetorical skills to do the government’s work:

. . . The role of the civil service exams in ensuring only men of merit entered the civil service increased significantly… The Rules of Writing was written as a guide for men who wanted to enter a career in the civil service and who needed to pass the strict series of civil service exams in order to do so. (Kirkpatrick and Xu 5)

What we have received by way of the Greeks and Romans as rhetoric is just one version of a set of universal human activities related to thinking, talking, judging, writing, debating, and persuading each other. Every culture establishes expectations for communicating persuasively and appropriately. Traditions and cultural norms maintain expectations, but social change may disrupt these expectations or necessitate their evolution. For these reasons and more, the art of rhetoric is complex and fascinating to study.

Discussion: Rhetoric & Politics

Politics is rhetorical and rhetoric is political, but too often people use the terms interchangeably. Politics is about getting things done with groups of people, or, as Saylor Academy puts it: “Politics describes the use of power and the distribution of resources.” Since any political activity requires persuasion to get groups of people to share power and resources, politics usually relies on rhetoric. But politics may set aside persuasive strategies to find other ways to effect change. For example, law and war can be coercive instead of persuasive, and may be a part of how political decisions are enforced as opposed to decided on by two or more consenting parties.

We often hear that a senator or president or mayor is using rhetoric, as when someone says, “That kind of rhetoric is dangerous!” Rhetoric is also often misunderstood as “just talk.” You’ve probably heard people’s positions dismissed as “mere rhetoric.” This way of talking about rhetoric dismisses the power of words to implement change—through talking, writing, and creating. Talk is powerful stuff. It’s so powerful that there are whole disciplines devoted to understanding it (communication studies, education and teaching, literary criticism, philosophy, and, yes, rhetoric as a discipline). The next time you hear the word rhetoric used by politicians, political analysts, or in media editorials, think about their intention. Are they dismissing another person’s viewpoint by implying that it’s just a bunch of hot air? Are they implying that another person’s stated position on an issue is somehow inherently dangerous? Or do they use the word “rhetoric” in a way that indicates they really understand the tactics of persuasion that may be at work?

And yet, classical rhetoric certainly has political roots. The Greco-Roman tradition categorizes speeches into three categories, which include forensic, deliberative, and epideictic. Forensic has to do with making a believable case for what happened—as is the case when someone tries to prove their innocence to a jury by offering evidence for an alibi. Epideictic texts or speeches are for ceremony or show—to praise or to blame in ways that aren’t necessarily legally consequential. But the last speech type—the deliberative speech—has always been about getting an audience to adhere to a position on what actions should be taken. Deliberative rhetoric is clearly tied to politics and the “deliberate” drafting of legislation as one way of working with diverse groups of people. Of course, other aspects of our communication may be connected to politics in subtle ways. If someone writes an epideictic letter to a newspaper editor praising the life of former Texas governor Ann Richards, might we have some reason to take that praise as a public endorsement of Richards’ politics, too? Or if a nonprofit research team makes a forensic case that community access to arts and cultural events improves educational outcomes, we might read it as implying that arts should enjoy increased public funding. Politics, like rhetoric, is widespread and touches on nearly all aspects of our lives.

The relationship between rhetoric and politics is debatable, is itself a matter of discourse. One could argue that, because rhetoric always reflects or impacts our values, it always influences our politics. Or one could argue that human relation exists beyond the political and so too, therefore, does rhetoric.

What do you think?

Clarifying rhetoric vs. persuasion vs. argumentation

These three words are often used interchangeably for understandable reasons. It is important, however, to understand their distinctions:

- “Persuasion” is the action or fact of persuading someone (or of being persuaded yourself) to do or believe something. It is to be convinced. Persuasion can be benign, like when dentists convince us to floss every day so that our gums and teeth stay healthy. Persuasion can be profitable, like when Apple designs opulent packaging with smooth dimensions and surfaces to convince us to only purchase their products. Persuasion can be malicious or harmful, like when cigarette companies knew their products were deadly and continued to sell/market them or when politicians convince us a group of humans is evil and their deaths justifiable.

- “Argumentation” is the act or process of presenting reasons to convince someone of a particular argument (i.e. a claim or opinion). It is to make an assertion and prove it. Argumentation is embedded in persuasion and vice versa. For example, the dentist who persuades me to floss my teeth has made the arguments that 1) healthy gums and teeth are good and important and 2) that flossing keeps them healthy and has probably shown me images of improperly flossed mouths to convince me.

- “Rhetoric” is how persuasion and argument work. It is their mechanic. “Persuasion” and “argumentation” are nouns that refer to acts; “rhetoric” is a noun that refers to the act’s technique, its strategy, its methodology, its way of being/doing. Rhetoric is the thoughtwork the dentist did to assemble her argument to persuade me to floss and also the words, stories, images, tone of voice, and facial expression she deployed. All persuasion and all argument is rhetorical; it is a matter of intense scholarly debate whether all rhetoric is persuasive or argumentative.

What is rhetorical analysis?

“Rhetorical analysis” refers to methods we use to understand the power of language, signs, and symbols. Just like scientists deploy theories of relativity and evolution to understand the way the physical world physically moves, develops, and changes and why, scholars in the humanities deploy rhetorical theory to understand how the world is developed, changed, and moved via language, signs, and symbols. Rhetorical analysis helps to understand texts composed by others’ and also helps us compose our own texts.

Because communication and communicative texts have manifold components and move in manifold spaces, rhetorical analysis has many pieces. In the next two chapters, we will break down the foundational parts of rhetorical analysis. We have also made available in the Student Resources section, a chapter called “The Art of Rhetoric” which includes more strategies for thinking critically and strategically about your own and others’ persuasion and argumentation. Here is an outline of rhetorical analysis’ foundational components before we begin:

- Rhetorical Situation: context that shapes communication

- Rhetorical Appeals: strategies speakers deploy through specific text elements, messages, and claims to reach their audience

- Rhetorical Affects: how audiences respond and/or what a text does

The Rhetorical Situation

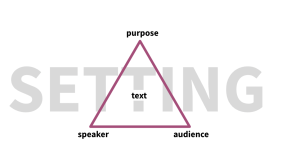

A key component of rhetorical analysis involves thinking carefully about the “rhetorical situation” of a text. We can understand the concept of a rhetorical situation if we examine it piece by piece, by looking carefully at the rhetorical concepts from which it is built. The philosopher Aristotle organized these concepts as speaker, audience, setting, purpose, and text. Answering the questions about these rhetorical concepts below will give you a good sense of your text’s rhetorical situation—the starting point for rhetorical analysis.

You can think of the rhetorical situation as the context or set of circumstances out of which a text arises. Any time anyone is trying to communicate, they are doing so within a particular context, one that influences and shapes the argument that is made. When we do a rhetorical analysis, we look carefully at how the rhetorical situation (context) shapes the rhetorical act (the text).

Identifying the rhetorical situation of a text requires critical thinking and research. We engage in this kind of thinking when we were are exposed to texts and also when we compose them. A marketing team, for example, conducts extensive research to identify and understand their target markets and target demographics. A research team applying for a grant is going to conduct research on the kinds of projects particular grant organizations fund, projects they have previously awarded, and criteria for their selections in order to choose the organizations to whom they submit and to compose their applications.

1. Speaker

The speaker of a text is the creator — the person who is communicating in order to try to effect a change in his or her audience. An author doesn’t have to be a single person or a person at all — an author could be an organization. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine the identity of the author and his or her background.

- What kind of experience or authority does the author have in the subject about which he or she is speaking?

- What values does the author have, either in general or with regard to this particular subject?

- How invested is the author in the topic of the text? In other words, what affects the author’s perspective on the topic?

- Example of author analysis for the rhetorical situation: (President Trump’s Inaugural Address) President Trump was a first-term president and someone who had not previously held political office. He did not yet have experience with running the country. He is, however, a wealthy businessman and had a great deal of experience in the business world. His political affiliation is with the Republican party – the conservative political party in America

Exercise: Researching Speaker Positionality

Positionality is a feminist concept that allows writers to identify, as Myfanwy Franks defines, “the way in which individual identity is positioned by others” (42). When we write, we need to determine the positionality of our audience and ourselves. Recognizing our positionality means acknowledging that our experiences can influence our perspective, expectations, and understanding in the situations we encounter. To help you recognize your own positionality in a rhetorical situation, consider asking yourself how the factors of gender, race, class, ethnicity, sexuality, nationality, ability, age, religion, political affiliation, veteran status, and other life experiences might influence a situation.

Analyzing our own positionality can help us identify our stance toward a topic or situation. An author’s stance could influence how information is presented, and for what audience. Authors make choices about how and what information they write, so we can look for an author’s stance in the language of their writing. Language is evidence of stance because the style and substance of writing showcases the writer’s perspective.

Select a source you’re planning to use in a piece you’re composing, and then do some background research on the author of that source to determine their positionality. For instance, you might search to find:

- The author’s current or past occupation

- An online CV or resume for the author

- Other publications by the author

- Public social media commentary

Reflect on what you’ve found by asking yourself: what do my findings tell me about the stance of the author on the topic I am researching. Is their stance obvious or do they take a more objective approach? Why might that be?

Read the source again to look for evidence of the author’s stance. Respond to the following questions in your research journal:

- What is this author’s stake in the topic

- How does this author establish credibility (ethos) on this topic?

- How does the author’s style of writing add to or align with their credibility?

- What kind of voice does the author use and how does it impact my perception of them, their words, and my relationship to them?

In any text, an author is attempting to engage an audience. Before we can analyze how effectively an author engages an audience, we must spend some time thinking about that audience. An audience is any person or group who is the intended recipient of the text and also the person/people the author is trying to influence. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine who the intended audience is by thinking about these things:

- Who is the author addressing?

- Sometimes this is the hardest question of all. We can get this information of “who is the author addressing” by looking at where an article is published or the venue through which communication took place. What audiences are likely to listen to Texas Public Radio? What audiences are likely to see a billboard in Waco along I-35? What audiences are likely to have a subscription to The San Antonio Express News? Who is most likely to be reading The Federalist blog page? Who hears a Presidential Address? Be sure to pay attention to the newspaper, magazine, website, or journal title where the text is published. Often, you can research that publication to get a good sense of who reads that publication. You can also better identify audience by researching a text’s historical, political, or cultural setting.

- What is the audience’s demographic information (age, gender, etc.)?

- What is/are the background, values, interests of the intended audience?

- How open is this intended audience to the author?

- What assumptions might the audience make about the author?

- In what context is the audience receiving the text?

As readers and writers, we need to ask these questions of any text so that we can understand the rhetorical situation. We need to determine the deep contextual meaning of a text to fully appreciate the argumentative, persuasive, and informative strategies present. Without knowing the context, we’ll fail to understand how an audience would respond to the text.

3. Setting

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and that includes the creation of any text. Essays, speeches, photos, political ads — any text — are written in a specific time and/or place by specific humans for specific humans, all of which affect the way the text communicates its message. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, we can identify the particular occasion or event that prompted the text’s creation at the particular time it was created.

-

- Was there a debate about the topic that the author of the text addresses? If so, what are (or were) the various perspectives within that debate?

- Did something specific occur that motivated the author to speak out?

- What was happening historically, socially, and culturally at the time the text was created?

Matters of time help us understand a text’s exigence–the motivation for its creation.

Example: Exigence and Audience in Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” Speech

Sojourner Truth first presented what has become known as her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at the Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851. This analysis is based on a transcript of her speech published a few weeks afterward by Marion Robinson in the Anti-Slavery Bugle. It is documented that Truth worked with Robinson on this transcript and approved its publication. These two different venues, the convention and the newspaper, tell us about Truth’s intended audiences and about her goals as a speaker. At the Woman’s Rights Convention, Truth was primarily addressing White women and men gathered “to consider the Rights, Duties, and Relations of Women” (Proceedings 2). This state conference included reports on education, labor, and common law, as well as letters from Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer. The Anti-Slavery Bugle was the newspaper of American minister and abolitionist Marius Robinson. It operated out of Salem, Ohio and circulated primarily in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and western Pennsylvania. Presented ten years before the outbreak of the Civil War, sixty years before women in the U.S. would gain the right to vote, Truth spoke at a moment of national tension, anxiety, hope, and anger.

Another important aspect of text setting is circulation–how a text moves across different spaces and how its meanings/affects/messages change as it moves. Social media has shown us how a text, written in a specific time and place, can take on new meaning as it circulates to different places at different times. Twitter posts that originally appeared on that platform can now be quoted in news articles, television programs, and even other social media sites, causing the text to take on new meaning as it circulates to new contexts. In the social media age of the internet, context shifts depending on how and where a text circulates.

To think about how texts circulate in culture is to consider how they get written, how they get shared, and how the meanings they carry move with them as they travel from context to context. These days such texts often include images, sound, and video, as well as words (for example, multimodal texts), and as the internet grows and expands, the circulation of texts, genres, and meaning all speed up, changing our writing and rhetorical practices in the process.

There are many ways to think about how texts circulate, from the posts we share online, to the memos we exchange at work, to the larger world of the public internet where texts and information circulate globally. Traditional print newspapers and magazines have long tracked their circulation and subscribers. However, in the digital spaces of the global internet, our experience of how writing and rhetoric move has radically changed, not only in how we write and communicate with friends and family, but also in the ways ideas flow through cultures and give shape to professional and public discourse about problems that matter.

Example: Meme Genre & Circulation

To illustrate how textual circulation works, let’s look at a quick example of a genre that exemplifies how texts circulate in modern writing environments: memes.

Nowadays, memes come in many forms and genres, but one of the most common kinds is what is known as the “advice animal image macro,”as seen in Image 1. Most of us are familiar with this kind of meme. Advice animal image macros like “success kid” are common memes that use the same image but add a different phrase at the top and bottom of the image. In the case of “success kid,” the top phrase states a problem (“Get sick on Friday”), and the bottom phrase states a serendipitous outcome (“Three day weekend”).

Like all memes, “success kid” has a history of development and circulation. The original image was taken in 2007 by Lindey Griner of her 11-month-old son Sammy and posted to Flickr to share with family (Image 2). The “I hate sandcastles” image was the first image meme to be circulated that used the little boy’s image (Image 3). Others soon picked up on the 2007 image and began altering it for their own rhetorical purposes. By 2008, the image was used by dozens of other people to convey either a sense of frustration, as in “I hate sandcastles,” or a feeling of unexpected success, giving birth to the now well-known “success kid” meme (Images 4 and 5).

Today, thousands of image macros have been spun from this original image, and “success kid” memes continue to circulate online as other meme creators draw on the shared meaning of the meme in new contexts. Thus, when considering textual circulation, we are looking at how texts get composed, how they reference and borrow meaning from each other, where they go, and the meanings they carry as they circulate.

4. Purpose

The purpose of a text connects the author with the setting and the audience. Looking at a text’s purpose means looking at the author’s motivations for creating it. The author has decided to start a conversation or join one that is already underway. Why has he or she decided to join in? In any text, the author may be trying to inform, to convince, to define, to announce, or to activate. Can you tell which one of those general purposes your author has?

-

- What is the author hoping to achieve with this text?

- Why did the author decide to join the “conversation” about the topic?

- What does the author want from their audience? What does the author want the audience to do once the text is communicated?

It can be difficult to surmise author intent. Sometimes the speaker will tell you what they are doing with phrases like “In this piece, I intend to…” or “It’s important that we understand…and, therefore, this article will…” Other times, the speaker is much more subtle and you will need to rely on textual (tone, content, information, organization, address, etc.) and contextual (genre, medium, publication venue, setting, etc.) clues.

Additional Resources: Author Intent & Purpose

Here are resources for thinking about purpose and intent that might help you:

Example of Purpose Analysis & Claim for Sojourner Truth’s Speech

In the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech and others, Truth sought to align the interests of abolitionists and suffragettes. She, therefore, makes herself legible to her audience of both abolitionists and suffragettes through gendered syllogisms and Biblical allusions, and creates common ground between her audiences through strategic parallelism and diction that highlights similarities in their positions and interests.

5. Text

“Text” refers to any form of communication, primarily written or oral, that forms a coherent unit, often as an object of study. A book can be a text and a speech can be a text. Social media posts, commercials, photographs, YouTube videos, clothing, food packaging, websites, and emails are all also texts.

Texts are made of elements or components. Elements range from the content the speaker chooses to include to specific words or sounds they deploy to overall tone and syntactical style they create to the arrangement of information and paragraphs to the formatting of a page. In the next chapter, we will talk more about identifying specific elements and components and thinking about how they work. We will also talk about rhetorical devices, specific kinds of text components recognized as useful to communication, persuasion, and argumentation.

Medium and genre are important feature of texts that influence or shape their other elements and their audiences. Medium refers to the media source or interface through which we communicate or receive a message or messages. Examples of media (the plural of medium) include newspapers, paintings, radio shows, podcasts, billboards, social-media apps, Zoom, or your course learning management system. In a sense, media are the materials that lie between the communicator and the communication. Different medium and genre forms are made of different text elements. For example, a newspaper article is going to be made primarily of words, their arrangement, their format, and the inclusion of charts, graphs, or photographs. A podcast is going to be made of words and also voices, intonations, sound effects, and music. A speech is going to made of words, voices, intonations, hand gestures, facial expressions,

To better understand a creator’s choice of medium, you might ask the following questions:

-

- In what medium is the text being made: image? written essay? speech? song? protest sign? meme? sculpture?

- What is gained by having a text composed in a particular format/medium?

- What limitations does that format/medium have?

- What opportunities for expression does that format/medium have (that perhaps other formats do not have?)

Again, research is often necessary to get to the answers to these questions and understand a text’s rhetorical situation.

Exercise: The Rhetorical Situation

Let’s begin exploring the rhetorical situation with a situation close to home. Take a few minutes to think or free write in order to remember a reasonably serious conversation you’ve had recently with a family member or friend. The subject of the conversation doesn’t matter much. You might choose a time you had an argument, either about an important matter, something that always crops up as an issue in your relationship. It’s also fine to focus on mundane, everyday issues, perhaps a dispute about whose turn it was to wash the dishes or to choose the restaurant. You don’t have to choose an argument. What about the time you shared really good news with family or friends? Think of conversations about favorite books, films, or after an exciting basketball game. Whatever you choose, make sure the conversation was with someone you know well about a common interest. Now share your reflections with classmates and others by working through these questions

- What was the topic of the conversation?

- What was the purpose of the conversation?

- Who was your primary audience?

- What was the purpose of the conversation?

- What was my audience’s opinion toward the topic?

- What kinds of background information did you need to provide to your audience?

- What kinds and how specific were the details in your conversation?

- What was your tone, style of delivery? What words did you use?

Taking into account your audience’s needs, opinions, and attitudes before writing allows you to create a document that is more understandable. With this information now in mind, what could have been changed in the conversation you recounted here to make the purpose of that discussion clearer or your point more understood by the person with whom you were communicating?

Rhetorical appeals

If the rhetorical situation refers to what texts are part of and text elements refers to what texts are made of, then rhetorical appeals are what the text is composed to do and how the author intends the text to work. Rhetorical appeals are the qualities of an argument that make it persuasive or the qualities of communication that, in some way, move audiences.

Aristotle came up with three ways rhetorical appeals work. He taught that a speaker’s ability to persuade an audience is based on how well the speaker appeals to that audience in three different areas: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Ethos: appeal to credibility and character

Ethos is the appeal focused on the writer. It refers to the character of the writer, including her credibility and trustworthiness. Credibility refers to speaker’s knowledge and expertise in the subject at hand. Character is who a person is based on their history, experiences, choices, personality, and values. Appealing to ethos changes depending on the rhetorical situation, the audience addressed, and the genre the author is writing in. For example, for lab reports and academic publication, the reader must be convinced that the author is an expert, is knowledgeable in their field, is a trustworthy researcher, and that their work merits attention. Alternatively, for a politician, constituents must be convinced their representative has intentions that align with their, that they can trust them with to understand and act on behalf of their needs and desires, and is capable of leadership and negotiation amongst other politicians.

On the one hand, when an author makes an ethical appeal, they are attempting to tap into the values or ideologies that the audience holds. Examples include patriotism, tradition, justice, equality, dignity for all humankind, self-preservation, or other specific social, religious or philosophical values (Christian values, socialism, capitalism, feminism, etc.). These values can sometimes feel very close to emotions and therefore also work as pathos. Speakers use values to identify themselves as ethical or trustworthy and also use values to tap into their audiences’ passionate beliefs.

Ethos is present in text’s in texts in two ways. First, through the author’s certification, reputation, or experience—in other words, who they are known to be in the world. For example, readers are more likely to trust health advice from a medical doctor than a carpenter and should listen to a carpenter about their house frame before they listen to medical doctor. In court, juries are more likely to trust testimony from an eyewitness than someone who heard about a crime from a friend. This kind of ethos is communicated through information the writer offers about themselves in their text or byline or can be found through research. Famous speakers have an ethos they’ve built through an accumulation of texts, interviews, appearances, etc. that they rely on for credibility and authority. Second, through the author’s creation or representation of themselves in the text. Speakers create ethos through their text component choices like voice, point of view, diction, grammar, style, information, description, etc.

Pathos: appeal to emotion

Pathos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the reader. Pathos refers to the emotions that are stirred in the reader while reading the manuscript. The author should seek to trigger specific emotional reactions in their writing. An author using pathos appeals wants the audience to feel something: anger, pride, joy, rage, happiness, superiority, inferiority, fear, worry, embarrassed, annoyance, anger, etc. For example, many of us have seen the ASPCA commercials that use photographs of injured puppies, or sad-looking kittens, and slow, depressing music to emotionally persuade their audience to donate money. This is a classic example of the use of pathos in argument.

Pathos-based rhetorical strategies are any strategies that get the audience to “open up” to the topic, the argument, or to the author through an emotional connection. Emotions can make us vulnerable and an author can use this vulnerability to get the audience to believe that their argument is a compelling one.

Pathos appeals might include:

- Expressive descriptions of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel or experience those events

- Vivid imagery of people, places or events that help the reader to feel like they are seeing those events

- Sharing personal stories that make the reader feel a connection to, or empathy for, the person being described

- Using emotion-laden vocabulary as a way to put the reader into that specific emotional mindset (what is the author trying to make the audience feel? and how are they doing that?)

- Using any information that will evoke an emotional response from the audience. This could involve making the audience feel empathy or disgust for the person/group/event being discussed, or perhaps connection to or rejection of the person/group/event being discussed.

Logos: appeal to logic

Logos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the argument or reason(s) being presented by the author. It is an appeal to rationality, referring to the clarity and logical integrity of the argument. Logos is, therefore, primarily rooted in the reasoning that holds different elements of the manuscript’s argument together. Do the findings logically connect to support the conclusion being drawn? Does the evidence support the author’s claim? Does the speaker’s argument make sense?

When an author relies on logos, it means that they are using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. Objective evidence is anything that can be proven with statistics or other facts via more than one source. Oftentimes that evidence has been validated by more than one authority in the field of study.

Remember, that what counts as “evidence” and “logic” is different across different communities and across topics. A group of scientists is going to consider peer-reviewed experiment-based findings adequate evidence; they are probably not going to consider a memoir adequate evidence. Humanities scholars are going to consider archival documents and primary accounts adequate evidence. YouTube videos or social media posts might work as evidence for some claims but not others. Religious texts, similarly, are going to resonate with particular audiences and particular arguments and not others. This is one reason modern discourse is so complicated: what seems completely reasonable to one group of people is nonsensical to another and the media makes little effort to account for worldviews.

Logical appeals rest on rational modes of thinking, such as:

- Comparison: a comparison between one thing (with regard to your topic) and another, similar thing to help support your claim. It is important that the comparison is fair and valid – the things being compared must share significant traits of similarity.

- Cause/effect thinking: you argue that X has caused Y, or that X is likely to cause Y to help support your claim. Be careful with the latter – it can be difficult to predict that something “will” happen in the future.

- Deductive reasoning: starting with a broad, general claim/example and using it to support a more specific point or claim (picture an hourglass where the sands gather in the middle)

- Inductive reasoning: using several specific examples or cases to make a broad generalization (consider the old question of “if your friend jumped off of a bridge, would you” to make the sweeping claim that all young people are easily persuaded to follow the crowd)

- Analogical reasoning: moves from one particular claim/example to another, seemingly sequential (sometimes this line of reasoning is used to make a guilt by association claim)

- Exemplification: use of many examples or a variety of evidence to support a single point

- Elaboration: moving beyond just including a fact, but explaining the significance or relevance of that fact

- Coherent thought: maintaining a well-organized line of reasoning; not repeating ideas or jumping around

Finally, it is important to remember that ethos, logos, and pathos are not distinct, independent categories. They influence each other, they work together, and text components often make more than one kind of appeal. For example, if someone is arguing for better funding for child care services in Texas and they offer a story about being a single parent in Dallas, their narrative appeals to ethos by establishing their credibility and character through their personal experience, appeals to the audience’s emotions by describing their child and their hardship, and appeals to logic by offering eyewitness evidence that the current system is failing.

Rhetorical affects

“Affect” refers to how audience(s) respond, unconsciously and consciously, to a text. It can be helpful to consider affect as responses to particular appeals:

- Ethos: What does the audience now think about the speaker’s credibility and character? Do they trust the speaker? Do they like them? Do they identify with them?

- Pathos: What did the audience feel while experiencing the text and what do they feel after exposure to it? Were their senses triggered? Were they reminded of particular experiences they have had?

- Logos: Does the audience understand why the author thinks the way they think? Do they think they were given sufficient, quality evidence? Do they get the primary claim? Do they feel like the piece is logical?

Remember, different audiences are going to respond differently to the same texts depending on their values, beliefs, experiences, education, perspectives, investments, needs, and desires. You can do research to predict or even prove how audience’s respond to particular kinds of texts. We now, for better and for worse, have access to affect and response through: comments sections, TikTok videos, online reviews, posts or tweets, editorials. You can also interview people in your class or your community to discover their response. Finally, don’t forget that YOU are a member of the audience. How the text affected you tells you something about it.

Exercise: Rhetorical Précis

A rhetorical précis (pronounced pray-see) differs from a summary in that it is a less neutral, more analytical condensation of both the content and method of the original text. If you think of a summary as primarily a brief representation of what a text says, then you might think of the rhetorical précis as a brief representation of what a text both says and does. Although less common than a summary, a rhetorical précis is a particularly useful way to sum up your understanding of how a text works rhetorically.

The rhetorical précis assignment helps you to summarize a ten to twenty-five page article into five succinct, concise sentences which will allow you to remember the important points of the article. Writing a precis, a shorter version of an article annotation, for everything you read in all of your college classes will also help you keep track of valuable information, organize articles and other sources for your research papers, and help you build your own set of resources for your classes and future career. Writing précis can be an excellent study skill, particularly for essay exams that allow you to bring your own notes, or just to help you weed out the less important information and hone in on the things you really need to learn.

THE STRUCTURE OF A RHETORICAL PRÉCIS:

Sentence One: Name of author, genre, and title of work, date in parentheses; a rhetorically active verb; and a THAT clause containing the major assertion or thesis in the text.

Sentence Two: An explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis.

Sentence Three: A statement of the author’s apparent purpose, followed by an “in order to” phrase.

Sentence Four: A description of the intended audience and/or the relationship the author establishes with the audience.

Sentence Five: An analysis of the significance or importance of this work.

Time to Practice:

Read this essay: “Writing as Reckoning”

Read the essay once and try to find the thesis statement, author’s purpose, audience, and why the author feels this work is important or significant to the field of study. Practice writing out a precis.

Additional Resources

Want to learn more? We recommend checking out a few more articles if you’d like to learn more about rhetoric:

- Opinion Article on Confirmation bias

- A Short and Highly Idiosyncratic History of Rhetoric

- What Do Students Need to Know About Rhetoric?

- Five Features of Better Arguments

- Political History of the Birth of Rhetoric

Attributions

“Virtual Communication” (COMM543 – 21ST CENTURY COMMUNICATION), Steve Covello, CC BY-NC 2.0.

“Breaking Down an Image,” Jenna Pack Sheffield, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, https://writingcommons.org/authors/jenna-pack-sheffield/.

“Types of Rhetorical Modes,” Lumen Learning, CC BY-SA, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-writing/chapter/types-of-rhetorical-modes/

“What is the Rhetorical Situation?,” Robin Jeffrey and Emilie Zickel, CC BY 4.0, https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/rhetorical-situation-the-context/.

“Types of Rhetorical Modes,” Lumen Learning, CC BY-SA, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-writing/chapter/types-of-rhetorical-modes/

“What is the Rhetorical Situation?,” Robin Jeffrey and Emilie Zickel, CC BY 4.0, https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/rhetorical-situation-the-context/.

Melanie Gagich; Emilie Zickel; and Terri Pantuso. “Rhetorical Appeals: Ethos, Logos & Pathos Defined. ” Texas A&M University Libraries. Informed Arguments: A Guide to Writing and Research.” https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/informedarguments/chapter/rhetorical-appeals-logos-pathos-and-ethos-defined/