17 Syntax & Style

What is “syntax”?

Syntax refers to sentence structure, the ways linguistic elements like words and punctuation are arranged to create meaning. Sentence length is a matter of syntax, as are complexity and the arrangement of clauses. Choosing different kinds of syntax allows writers to create their voice, persona, and particular meaning.

What is “diction”?

“Diction” refers to word choice and how writers assemble meaning by putting together certain words based on their sounds, literal meaning, and cultural connotations.

What is sentence “style”?

“Style” is the way something is written, as opposed to the meaning of what is written. It refers to the way a writer constructs their sentences (syntax), chooses their words (diction), and uses their tone. “Style” is like an aesthetic; it carries the writer’s personality and influences their relationship to their readers. “Style” is often linked to particular genres. “Academic writing,” for example, is a genre that tends to require a particular style: formal, thoughtful, neutral, and authoritative. “Style” is not meaning but style influences meaning.

This list of elements of style include:

- sentence structure

- word choice or diction

- active or passive voice

- verb tense

- mood or tone

Sentence Structure

The Basics: Terms to Know, Sentence Elements, and Functions

Subject: Usually contains a noun or pronoun and is the topic of the sentence and does an action.

Predicate: This is the action that the subject does.

Independent clause: Contains a subject and predicate and can stand alone as a sentence. ( Ex. I run., He eats., They laugh.)

Dependent (subordinate) clause: Group of words that can’t stand alone as a complete sentence, but is dependent on, or subordinate to, the independent clause. (Ex. Although I run,).

Inverted sentence: When the writer inverts the subject-predicate order and places the action before the subject. (Ex. Never has she felt so beautiful.)

Direct vs. Indirect object: Ex. Sally bakes Joe a cake. The cake receives the action of being baked, which makes it the direct object; however, the cake is baked for Joe, so he is the indirect object.

Prepositional phrase: A word that indicates a relationship from one thing to another. Ex. around, up, under, in, and so on.

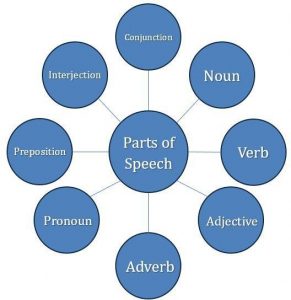

What are the different parts of speech and how do they function?

Parts of Speech:

Nouns – Persons, places, things, or ideas; function in a sentence as subject, direct object, indirect object, object complement, predicate nominative, object of a preposition, or appositive

Verbs – Actions or states of being; function in a sentence as either an action verb or a linking verb.

Pronouns – Words that take the place of nouns: function in a sentence as subject, direct object, indirect object, object compliment, predicate nominative, object of a preposition, or appositive

Adjectives – Describe nouns

Adverbs – Describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs

Prepositions – Words that signal prepositional phrases and show relationships between words and phrases; function in a sentence as either an adjective or an adverb

Conjunctions – Words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses; coordinating or subordinate.

Sentence constructions follow these basic patterns:

Subject/ verb: The dog ran.

Subject/ linking verb/ subject compliment: The dog is a German Shepard.

Subject /action verb/ direct object: The dog bit the mailman.

Subject/ action verb/ indirect object/ direct object: The dog brought me a stick.

Subject/ action verb/ direct object/ object compliment: The dog made the mailman angry.

The types of sentences:

Declarative: Makes a statement. The dog is sleeping in the corner.

Interrogative: Asks a question. Where is the dog?

Imperative: Gives a command. Come here, dog.

Exclamative: Expresses surprise. Look at that sweet dog!

*Use the four types of sentences to vary sentence length and style, as well as to:

- Avoid monotony.

- Provide rhythm.

- Create cohesion.

- Ensure clarity.

- Convey voice.

Further Reading:

Walden University’s website page “Grammar: Sentence Structure and Sentence Types” refers to and defines all of the important sentence parts: Sentence Parts Reference Guide

Ways to Vary a Sentence:

Avoid Repeating To-be Verbs:

-

- Writing is what I enjoy. 🡪 I enjoy writing.

- Smoking is bad for your health. 🡪 Smoking can cause bad health effects.

- Strengthens your statement, especially in an argument.

Combine Multiple Simple Sentences:

-

- We write. We edit. 🡪 We write, and we edit.

- He went to the store. He bought apples. 🡪 When he went to the store, he bought apples.

- Provides a smoother feel and shows relationships between ideas.

- Avoids a string of short, choppy sentences.

Use the FANBOYS acronym for remembering coordinating conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So

- Vary Location of Dependent Clauses and Phrases:

- When he went to the store, he bought apples.

- He bought apples when he went to the store.

- He bought apples when he went to the store, but she bought bananas.

Use subordinating conjunctions for creating dependent clauses: that, which, who, whom, whose, when, where, why, after, although, as, as if, because, since, so that, how, whenever, and so on.

Utilize Transition Words and Phrases:

-

- We write; however, we write and write again.

- Next, we will edit.

- Provides a smooth flow.

- Guides the reader through your thought process.

Conjunctive adverbs include: thus, therefore, thereby, consequently, however, additionally, furthermore, nonetheless, moreover, likewise, and so on.

Use Parallel Structure

Sentence elements that are alike in function should also be alike in construction, or parallel. Below are some examples of parallel elements. Notice the patterns in language:

-

- Ex: thinking, running, singing, seeing (Gerunds: Notice the “-ing” ending verbs)

- Ex: to see, to understand, to speak, to stir (Infinitives: The word “to” and then a verb)

- Ex: on the street, on the table, on the radio, on the mark (Prepositions: The words “on the” and a noun)

- Ex: who you are, what you are doing, why you are here (Clauses: The five Ws and how)

There are five rules on correct parallel usage:

- Coordinating conjunctions: With coordinating conjunctions or FANBOYS.

(FANBOYS: For, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so)

-

- Ex: She likes to look but not to listen.

- Ex: I do not enjoy running or dieting.

- Lists: In a list of three or more items.

-

- Ex: There wasn’t any opportunity to do my taxes, to request an extension, or to explain my situation.

- Ex: The company doesn’t care about who you are, how you got there, or why you have come.

- Comparisons: We often use such as, more, less, better, and worse and link them to words like as and than, but this not always the case.

-

- Ex: Driving to New York can take more time than flying there.

- Ex: How you live your life is just as important as how happy you are.

- Infinitives and being: Use parallel structure with elements joined by a linking verb or verb of being.

-

- Ex: Being Jim’s friend means being a fan of reggae music.

- Ex: To know her is to love her.

- Correlative conjunctions. Correlative conjunction must be used in pairs: Either/or, neither/nor, both/and, and not only/but also.

-

- Ex: We were told to either reduce the staff or find new customers.

- Ex: Angela was neither going to classes nor planning on graduating.

- Ex: I would like to buy both a new house and a new car.

Further Reading:

Here is an excellent guide to sentence style: Purdue Owl Sentence Style Guide

Eliminating wordiness in writing: Eliminating Sentence Wordiness

Attributions

“Haley the Noble Dog” image by Kathy Quesenbury

“Winnie with the Flying Ears” image by Monica Prochnow

Often, beginning student writers’ primary concerns are about meeting page counts or source minimums to satisfy a particular assignment’s requirements. As students’ writing skills and confidences become stronger, however, they can start to focus less on filling pages and focus more on the craft of their writing, which can help enhance the thoughtfulness and clarity of their ideas.

There are two sets of meaning created when a student writes an essay:

- the writer’s main message

- the subtle but detailed style choices like diction that help to enhance that main message.

One way to improve on the quality of writing is to consider modifying your diction, or word choice, in a piece of writing.

Diction: An author’s choice of words, phrases, or sentences. Diction can be formal or informal depending on the needs of the document and expectations of the audience. Diction, therefore, concerns itself with emotional and cultural values of words and their ability to affect meaning.

Consider the word laugh. We all know what it means to laugh, but instead of merely writing laugh in a sentence, a clever writer may consider using alternative words and take advantage of the effects they create. Ponder the words giggle, cackle, and chuckle, all of which also mean to laugh, but note how they create distinctly different meanings within the same sentence.

Examples:

- The old lady’s giggle echoed throughout the quiet house. (silly, fun-filled, childlike, perhaps a bit naughty)

- The old lady’s cackle echoed throughout the quiet house. (scary, witch-like, intending evil)

- The old lady’s chuckle echoed throughout the quiet house. (explosive, sudden, loud sound)

Think how a simple word variation can not only change the meaning of a sentence, but it can establish an overall mood to the work itself.

Example

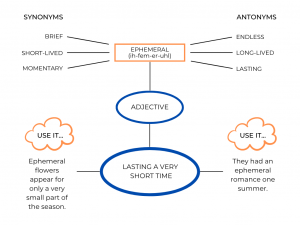

Here’s a graphic organizer to assist you in building your vocabulary:

This example illustrates the word “ephemeral” at the top, middle of the page, with a pronunciation key directly beneath the word. On the top, left of the page, under the heading Synonyms, are the words brief, short-lived, and momentary. On the top, right of the page, under the heading Antonyms, are the words endless, long-lived, and lasting. In the center of the page is the part of speech to which ephemeral belongs, adjective. Directly under adjective is a brief definition of ephemeral, lasting a very short time. On either side of the definition are examples of the word used in a sentence. On the bottom left is the sentence: Ephemeral flowers appear for only a very small part of the season. On the bottom right is the sentence: They had an ephemeral romance one summer.

Now here’s a blank one for you to fill in on your own: Blank Vocab Builder

Diction choices can include the use of:

- Slang. Recently coined words used informally. Ex: yeet, fleek,

- Colloquial expressions. Regional sayings like “y’all” and “you guys” that are informal.

- Jargon. Words or expressions that pertain to a particular profession or activity.

- Dialect. A nonstandard language style with its own vocabulary and grammar patterns, usually using words that reveal a person’s social class, economic level, or ethnicity.

- Concrete diction: Words that describe physical qualities or conditions.

Samuel Johnson, famous lexicographer, looking stern. - Abstract diction: Words that describe ideas, emotions, conditions, or concepts that cannot be touched.

- Denotation: The exact, dictionary definition of a word, free of secondary definitions or emotion. Ex: That car is jacked up. (Translation = Someone slid a jack under the car and hoisted it up.)

- Connotation: The social meaning of a word, containing suggestions, emotional overtones, or other associations. Ex: The car is jacked up. (Translation = That car is messed up!)

- Euphemism: A nice way of saying something too ugly to utter. Ex: dead = passed away

- Synecdoche: A part of something used to refer to the whole of it. Ex: Nice wheels! (Wheels are a part of a car, but really, you’re referring to the whole car.)

- Metonymy: When a word/phrase refers to something related but doesn’t have to deal with any part of anything. Ex: Jana has a nice ride! (Here, a “ride” really means a car.)

Stylistic Choices:

In writing documents that are creative, a student writer may also rely on additional tools to create a desired effect.

Figurative Language: the use of words that dress up the message. Sometimes the words show comparisons, similarities, relationships, or the treatment of an object as being human-like. Whatever the tactic the author uses, it is meant to make the reader connect to the characters/events through lively description in a deeper way than if the author just said something plainly.

- Ex: “A single second, as big as a zeppelin, floated by.” -“Greasy Lake” by TC Boyle

Explanation: The author simply could have said that time seemed to have stood still at that precise moment, but he didn’t. Instead, he used a simile to tell the same idea but to create a more intense effect. The result, of course, is much more powerful.

Below are common types of figurative language.

- Similes. Comparing two different things using “like” or “as”

- Metaphors. Comparing two different things not using “like” or “as”

- Hyperbole. A severe exaggeration. “It’s a thousand degrees outside!”

- Apostrophe. Directly addressing a person, thing, or abstraction, such as “O Western Wind,” or “Ah, Sorrow…” and is sometimes seen in religious texts or odes.

- Onomatopoeia. A word whose sounds duplicate the sounds they describe. Ex: hiss, buzz, bang, murmur, meow, growl.

- Oxymoron. A phrase with contradictory parts. Ex: jumbo shrimp, Biggie Smalls, a cold sweat, pretty ugly.

- Paradox. Concepts or ideas that are contradictory to one another, yet, when placed together hold significant value on several levels. Ex: Here’s some advice: Never take my advice!

- Kenning. A newly created compound sentence or phrase to refer to a person, object, place, action or idea. Ex: Battle-sweat = blood, Sky-candle = sun, Whale-road = ocean

- Metonymy. The name of one thing for that of another of which it is associated. A crown (royal object) rests on his crown (part of a person’s head).

- Synecdoche. A part of something to refer to the whole. Ex: Get your butt in here! (Really, all of you.)

- Litotes. A discreet way of saying something unpleasant without directly using negativity. Ex: Not the brightest bulb (not very smart)

- Understatement: An ironic understatement meant to downplay a situation and make it seem less than what it really is. Ex: “He’s not the sharpest tool in the shed.” (Translation: He isn’t smart.)

It is important to know when to use plain, formal language and when it is appropriate to use a relaxed, playful, or descriptive language. Consider the purpose of your message and the expectations of your audience. If you are writing an expository essay or a resume, for example, then it would be better to use a plain style, but if you are writing a descriptive essay or a poem, then using figurative language would be more appropriate. The key to creating a written document with an appropriate style relies on two things: deciding which words you choose and the effect you wish to create with those words.

Students will sometimes confuse diction, which is about word choice, with syntax, which is word order.

The Thesaurus: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Good — Student writers are, by all means, encouraged to use a thesaurus. It is a helpful tool to use when you are:

- feeling repetitive in your word choices and need to find an alternative word

- when you know what you want to say but cannot quite figure out the right term to use

The Bad — A thesaurus is not, however, an appropriate tool to use:

- Spice up an essay to make you sound sophisticated; this is the wrong way to go about it. Focus, instead, on digging deep into the details your ideas and adding complexity to your ideas. The language should reflect the sophistication of the ideas, not override them.

The Ugly – Students will sometimes select words that they are unfamiliar with, and as a result, the wrong word can make the writing unclear and the overall message diluted.

As noted by Stephen King in the introductory quote, it is better to use clear, simple language that conveys a thoughtful but complex chain of ideas rather than an essay overwhelmed with fancy language that has only a few or overly simple concepts. The message is your priority, but the words you choose are the tools that help to deliver that message.

Consider, then, what you are trying to convey. If you are expressing urgency about an issue, then what kind of words related to urgency would you pick to convey that message? Sadness? Happiness? Anger?

The Wrong Way with the Wrong Word:

The most common writing mistake, according to Stanford University, that a student writer makes is choosing the wrong word. These mistakes can sometimes stem from simple misspelling issues (like confusing “from” and “form”) to larger problems like selecting the wrong word altogether (allusion vs. illusion). The wrong word choice can create confusion and cost a student writer some valuable points on his or her grade.

Use this link to Stanford University Grammar Resources so that you can review the list of commonly confused words to ensure you are choosing the right ones in your own writing.

What is Active vs Passive Voice?

A sentence written in active voice has a subject that performs the action of the verb. For example: The dog bit the mailman. The dog performs the action of biting.

A sentence in passive voice has almost a backwards arrangement. The subject and direct object of the example sentence are flipped: The mailman was bitten by the dog. Here, the subject mailman is not performing the action of the verb. He is not doing the biting.

Active voice is usually preferred to passive voice as active voice conveys meaning more clearly and more concisely. In the examples, “the dog / bit / the mailman” takes fewer words than “the mailman / was bitten / by / the dog.” Passive voice sentences usually contain “be” verbs and a prepositional phrase. Moreover, the brain has to slow down just a little bit to rearrange word order and decipher the meaning. However, passive voice can be preferred in specific situations, such as in scientific reports, an instance when the topic is most important and needs to fall in the subject position in a sentence: i.e., The gamma rays were dialed up to maximum force.

Further Reading

GCGLearnFree.org has posted an easy-to-follow Active vs. Passive video on YouTube: Active vs Passive Voice in Your Writing

Grammarly’s website details active and passive voice and suggests ways to switch passive to active: Writing in Active Voice

If you would rather listen to an explanation of active and passive voice, Mignon Fogarty, a. k. a. Grammar Girl, hosts a podcast that explains grammar topics in depth. Click here for her podcast on active voice.

Here’s a follow-up to Grammar Girl’s podcast on active voice.

Click here for Grammar Girl’s podcast on passive voice, which furthers a clearer understanding of active voice as well.