19 Syntax & Style

It’s a complicated thing, putting ideas into words. For every feeling we have we want to tell someone, every experience we want to narrate, every notion we want to share, every bit of knowledge we want to explain, there are an infinite number of ways to compose sentences that do so. In this section, we establish some foundational terms for deconstructing and composing sentences and then review mechanics for each.

Often, beginning student writers’ primary concerns are about meeting page counts or source minimums to satisfy a particular assignment’s requirements. As students’ writing skills and confidences become stronger, however, they can start to focus less on filling pages and focus more on the craft of their writing, which can help enhance the thoughtfulness and clarity of their ideas.

There are two sets of meaning created when a student writes an essay:

- the writer’s main message

- the subtle but detailed style choices like syntax, style, and diction that help to enhance that main message.

What is “syntax”?

Syntax refers to sentence structure, the ways linguistic elements like words and punctuation are arranged to create meaning. Sentence length is a matter of syntax, as are complexity and the arrangement of clauses. Choosing different kinds of syntax allows writers to create their voice, persona, and particular meaning.

What is “diction”?

“Diction” refers to word choice and how writers assemble meaning by putting together certain words based on their sounds, literal meaning, and cultural connotations.

What is “style”?

“Style” is the way something is written, as opposed to the meaning of what is written. It refers to the way a writer constructs their sentences (syntax), chooses their words (diction), and uses their tone. “Style” is like an aesthetic; it carries the writer’s personality and influences their relationship to their readers. “Style” is often linked to particular genres. “Academic writing,” for example, is a genre that tends to require a particular style: formal, thoughtful, neutral, and authoritative. “Style” is not meaning but style influences meaning.

This list of elements of style include:

- sentence structure

- word choice or diction

- active or passive voice

- verb tense

- mood or tone

Syntax

Parts of a Sentence

Subject: Usually contains a noun or pronoun and is the topic of the sentence and does an action.

Predicate: This is the action that the subject does.

Direct vs. Indirect object: Ex. Sally bakes Joe a cake. The cake receives the action of being baked, which makes it the direct object; however, the cake is baked for Joe, so he is the indirect object.

Independent clause: Contains a subject and predicate and can stand alone as a sentence. ( Ex. I run., He eats., They laugh.)

Dependent (subordinate) clause: Group of words that can’t stand alone as a complete sentence, but is dependent on, or subordinate to, the independent clause. (Ex. Although I run,).

Prepositional phrase: a group of words that begins with a preposition (and ends with a noun, pronoun, or noun phrase (this noun, pronoun, or noun phrase is the object of the preposition). Prepositional phrases modify or describe nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs and are used to clarify relationships in sentences. Some of the most common prepositions that begin prepositional phrases are to, of, about, at, before, after, by, behind, during, for, from, in, over, under, and with.

Parts of Speech

Nouns: Persons, places, things, or ideas; function in a sentence as subject, direct object, indirect object, object complement, predicate nominative, object of a preposition, or appositive

Verbs: Actions or states of being; function in a sentence as either an action verb or a linking verb.

Pronouns: Words that take the place of nouns: function in a sentence as subject, direct object, indirect object, object compliment, predicate nominative, object of a preposition, or appositive

Adjectives: Describe nouns

Adverbs: Describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs

Prepositions: Words that signal prepositional phrases and show relationships between words and phrases; function in a sentence as either an adjective or an adverb

Conjunctions: Words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses; coordinating or subordinate.

What are the different parts of speech and how do they function?

Basic Sentence Patterns

Subject/ verb: The dog ran.

Subject/ linking verb/ subject compliment: The dog is a German Shepard.

Subject /action verb/ direct object: The dog bit the mailman.

Subject/ action verb/ indirect object/ direct object: The dog brought me a stick.

Subject/ action verb/ direct object/ object compliment: The dog made the mailman angry.

Types of Sentences

Declarative: Makes a statement. The dog is sleeping in the corner.

Interrogative: Asks a question. Where is the dog?

Imperative: Gives a command. Come here, dog.

Exclamative: Expresses surprise. Look at that sweet dog!

Use the four types of sentences to vary sentence length and style, as well as to:

- Avoid monotony.

- Provide rhythm.

- Create cohesion.

- Ensure clarity.

- Convey voice.

Helpful Resource

Walden University’s website page “Grammar: Sentence Structure and Sentence Types” refers to and defines all of the important sentence parts: Sentence Parts Reference Guide

Ways to Vary Sentences

1. Avoid repeating “to-be” verbs to strengthen your statement, especially in an argument.

-

- Writing is what I enjoy > I enjoy writing.

- Smoking is bad for your health > Smoking causes damage to your health > Smoking destroys parts of your body

2. Combine multiple simple sentences to create a smoother feel and show relationships between ideas. OR break up sentences into smaller ones if you want to jolt your reader. Use the FANBOYS acronym for remembering coordinating conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So

-

- We write. We edit. vs. We write and we edit.

- He went to the store. He bought apples. vs. He went to the store to buy apples

3. Vary the location of dependent clauses and phrases. Use subordinating conjunctions for creating dependent clauses: that, which, who, whom, whose, when, where, why, after, although, as, as if, because, since, so that, how, whenever, and so on.

-

- When he went to the store, he bought apples.

- He bought apples when he went to the store.

- He bought apples when he went to the store, but she bought bananas.

4. Utilize transition words and phrases to guide your reader through your thought process and create flow. You can also use conjunctive adverbs like: thus, therefore, thereby, consequently, however, additionally, furthermore, nonetheless, moreover, likewise, and so on.

-

- I went to the grocery store and considered buying kiwis, but then I remembered my roommate doesn’t like kiwis and bought apples instead.

- I went to the grocery store and considered purchasing kiwis. However, upon reaching the produce section, I remembered my roommate does not care for kiwis, and therefore purchased apples instead.

5. Use parallel structure. Sentence elements that are alike in function should also be alike in construction, or parallel. Below are some examples of parallel elements. Notice the patterns in language:

-

- thinking, running, singing, seeing (Gerunds: Notice the “-ing” ending verbs)

- to see, to understand, to speak, to stir (Infinitives: The word “to” and then a verb)

- on the street, on the table, on the radio, on the mark (Prepositions: The words “on the” and a noun)

- who you are, what you are doing, why you are here (Clauses: The five Ws and how)

There are five rules on correct parallel usage:

-

- Coordinating conjunctions: With coordinating conjunctions or FANBOYS.

-

-

-

- Ex: She likes to look but not to listen.

- Ex: I do not enjoy running or dieting.

-

-

-

- Lists: In a list of three or more items.

-

-

-

- Ex: There wasn’t any opportunity to do my taxes, to request an extension, or to explain my situation.

- Ex: The company doesn’t care about who you are, how you got there, or why you have come.

-

-

-

- Comparisons: We often use such as, more, less, better, and worse and link them to words like as and than, but this not always the case.

-

-

-

- Ex: Driving to New York can take more time than flying there.

- Ex: How you live your life is just as important as how happy you are.

-

-

-

- Infinitives and being: Use parallel structure with elements joined by a linking verb or verb of being.

-

-

-

- Ex: Being Jim’s friend means being a fan of reggae music.

- Ex: To know her is to love her.

-

-

-

- Correlative conjunctions. Correlative conjunction must be used in pairs: Either/or, neither/nor, both/and, and not only/but also.

-

-

-

- Ex: We were told to either reduce the staff or find new customers.

- Ex: Angela was neither going to classes nor planning on graduating.

- Ex: I would like to buy both a new house and a new car.

-

-

Helpful Resources

Here is an excellent guide to sentence style: Purdue Owl Sentence Style Guide

Eliminating wordiness in writing: Eliminating Sentence Wordiness

Diction

Another way to improve on the quality of writing is to consider modifying your diction, or word choice, in a piece of writing. Diction refers to an author’s choice of words, phrases, or sentences. Diction can be formal or informal depending on the needs of the document and expectations of the audience. Diction, therefore, concerns itself with emotional and cultural values of words and their ability to affect meaning.

Consider the word “laugh.” We all know what it means to laugh, but instead of merely writing laugh in a sentence, a clever writer may consider using alternative words and take advantage of the effects they create. Ponder the words giggle, cackle, and chuckle, all of which also mean to laugh, but note how they create distinctly different meanings within the same sentence.

Examples:

- The old lady’s giggle echoed throughout the quiet house. (silly, fun-filled, childlike, perhaps a bit naughty)

- The old lady’s cackle echoed throughout the quiet house. (scary, witch-like, intending evil)

- The old lady’s chuckle echoed throughout the quiet house. (explosive, sudden, loud sound)

These sentences show how a simple word variation can not only change the meaning of a sentence, but it can establish an overall mood to the work itself.

Diction choices can include the use of:

- Slang. Recently coined words used informally. Ex: yeet, fleek,

- Colloquial expressions. Regional sayings like “y’all” and “you guys” that are informal.

- Jargon. Words or expressions that pertain to a particular profession or activity.

- Dialect. A language style with its own vocabulary and grammar patterns, usually using words that reveal a person’s social class, economic level, or ethnicity.

- Concrete diction: Words that describe physical qualities or conditions.

Samuel Johnson, famous lexicographer, looking stern. - Abstract diction: Words that describe ideas, emotions, conditions, or concepts that cannot be touched.

- Denotation: The exact, dictionary definition of a word, free of secondary definitions or emotion. Ex: That car is jacked up. (Translation = Someone slid a jack under the car and hoisted it up.)

- Connotation: The social meaning of a word, containing suggestions, emotional overtones, or other associations. Ex: The car is jacked up. (Translation = That car is messed up!)

- Euphemism: A nice way of saying something too ugly to utter. Ex: dead = passed away

- Synecdoche: A part of something used to refer to the whole of it. Ex: Nice wheels! (Wheels are a part of a car, but really, you’re referring to the whole car.)

- Metonymy: When a word/phrase refers to something related but doesn’t have to deal with any part of anything. Ex: Jana has a nice ride! (Here, a “ride” really means a car.)

Practice: Vocab/Diction Builder

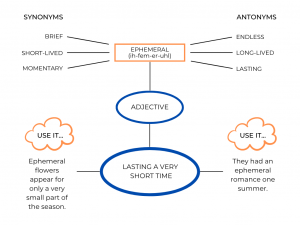

Below is a mindmap, or graphic organizer, you can use to help you brainstorm vocabulary and alternative turns of phrase. This example illustrates the word “ephemeral” at the top, middle of the page, with a pronunciation key directly beneath the word. On the top, left of the page, under the heading Synonyms, are the words brief, short-lived, and momentary. On the top, right of the page, under the heading Antonyms, are the words endless, long-lived, and lasting. In the center of the page is the part of speech to which ephemeral belongs, adjective. Directly under adjective is a brief definition of ephemeral, lasting a very short time. On either side of the definition are examples of the word used in a sentence. On the bottom left is the sentence: Ephemeral flowers appear for only a very small part of the season. On the bottom right is the sentence: They had an ephemeral romance one summer. Now here’s a blank one for you to fill in on your own: Blank Vocab Builder

Now, an important question comes up re. diction: Should I use a thesaurus? The answer varies:

Answer 1: Absolutely! Use a thesaurus when you are feeling like your word choice is becoming repetitive or when you know what you want to say but can’t quite remember the right word

Answer 2: Not always. You don’t want to use a thesaurus when you want to “sound smarter” or when you aren’t sure what synonyms’ connotations are or when you are trying to fill up space on your page and say the same thing in a slightly different way. Your writing should reflect you, your way of speaking, your language, your voice, your knowledge, your ideas. Use words and phrases you understand (in creative ways if necessary!), dig into the details of your ideas, and you will show your reader how smart you are.

Style

Style is difficult to pin down and define. It’s a speaker’s aesthetic, their unique and indelible way of speaking. Their personality preserved and communicated in a text. Think about writers you like to read, musicians you like to listen to, or people you like to hear speak. Do you recognize their voice or sound without being told who is speaking? Can’t you distinguish between writers without being told who is who? Style is made of many things: voice, tone, perspective, diction, syntax, cadence, etc. Below are elements that constitute writers’ different styles.

When thinking about style, it is important to consider genre and your goal in relation to the community invested in a particular genre. If you are trying to speak to a group of scientists and want to be seen as one of them, you probably wouldn’t include metaphor or personification. You probably would use “I” but in a neutral, observational capacity rather than a feeling one—unless, of course, your goal is to shake things up and admit bias or convey through emotion and narrative the exigency of a particular project.

Figurative Language

Figurative language is a type of communication that does not rely on a word’s direct definition, but uses different words to convey meaning.For example, when you say you have “butterflies in your stomach,” you are speaking figuratively to embody fluttering, panicked nerves. Common in comparisons and exaggerations, figurative language is usually used to add creative flourish to written or spoken language or explain a complicated idea. Whatever the tactic the author uses, it is meant to make the reader connect to the characters/events through lively description in a deeper way than if the author just said something plainly.

- Ex: “A single second, as big as a zeppelin, floated by.” -“Greasy Lake” by TC Boyle

Explanation: The author simply could have said that time seemed to have stood still at that precise moment, but he didn’t. Instead, he used a simile to tell the same idea but to create a more intense effect. The result, of course, is much more powerful.

Below are common types of figurative language.

- Similes. Comparing two different things using “like” or “as”

- Metaphors. Comparing two different things not using “like” or “as”

- Hyperbole. A severe exaggeration. “It’s a thousand degrees outside!”

- Apostrophe. Directly addressing a person, thing, or abstraction, such as “O Western Wind,” or “Ah, Sorrow…” and is sometimes seen in religious texts or odes.

- Onomatopoeia. A word whose sounds duplicate the sounds they describe. Ex: hiss, buzz, bang, murmur, meow, growl.

- Oxymoron. A phrase with contradictory parts. Ex: jumbo shrimp, Biggie Smalls, a cold sweat, pretty ugly.

- Paradox. Concepts or ideas that are contradictory to one another, yet, when placed together hold significant value on several levels. Ex: Here’s some advice: Never take my advice!

- Kenning. A newly created compound sentence or phrase to refer to a person, object, place, action or idea. Ex: Battle-sweat = blood, Sky-candle = sun, Whale-road = ocean

- Metonymy. The name of one thing for that of another of which it is associated. A crown (royal object) rests on his crown (part of a person’s head).

- Synecdoche. A part of something to refer to the whole. Ex: Get your butt in here! (Really, all of you.)

- Litotes. A discreet way of saying something unpleasant without directly using negativity. Ex: Not the brightest bulb (not very smart)

- Understatement: An ironic understatement meant to downplay a situation and make it seem less than what it really is. Ex: “He’s not the sharpest tool in the shed.”

Imagery

In terms of writing, imagery is more than creating a pretty picture for the reader. Imagery pertains to a technique for the writer to appeal to the reader’s five senses as a means to convey the essence of an event. It means to recreate a thing, bring it to life, in the reader’s imagination. The five senses include sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste. The writer does not need to employ all five senses, only those senses that most effectively convey, transport the reader into that event. Imagery engages the reader with specific sensory details. Imagery creates atmosphere/mood, causing the reader to feel a certain emotion. For example, a scary scene includes details that cause a reader to be frightened.

Example: Imagery

“The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the habiliments of the grave. The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have had difficulty in detecting the cheat. And yet all this might have been endured, if not approved, by the mad revellers around. But the mummer had gone so far as to assume the type of the Red Death. His vesture was dabbled in blood — and his broad brow, with all the features of the face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.” – “Masque of the Red Death,” Edgar Allan Poe

Imagery can be used throughout an entire essay, such as a description essay that focuses on a particular event. Writers should first decide what atmosphere/mood they want to create for their readers and then focus solely on the sensory details that convey that particular atmosphere/mood. For example, if a writer wanted to share the experience of a favorite holiday meal, then s/he would focus on the smells and tastes of all the food and the memories that those smells and tastes conjure. The hectic grocery shopping for all the ingredients would be omitted since that would not express the nostalgia of the meal.

Imagery can also be used per individual paragraph as a means to illustrate a point. For example, in an essay arguing for a ban on smoking, one paragraph could detail the damage to lungs caused by smoking.

Practice: Imagery

A brainstorming technique for imagery involves drawing a picture by focusing on one sense at a time. So, find a blank sheet of paper and various colored pencils. You can do this activity in one of two ways; by (1) attuning to what is around you in the space you are in to practice sensing, or by (2) imagining a setting you love or miss or wish to tell someone about.

First is sight. Slow down to mentally picture every object, shape, color, person, and so on in the scene. Draw, as best you can, representations of each of those visual details. (Only you will see this drawing; no need to stress over perfection.)

Next, take a different sense, such as sounds, and record those sounds on paper with various colors, symbols, or onomatopoeia. (Again, do the best you can to represent what you heard. Your goal is to remind yourself of the sounds, not create a work of art.)

Next, take a different sense and record that particular sense on paper with various colors and symbols.

The objective is to slow down and focus on each sense individually rather than trying to remember the scene all at once. By slowing down and envisioning each sense on paper, you can determine which senses most accurately create the atmosphere/mood for the essay and then apply only those senses in the essay.

Helpful Resources

Oregon State University’s discussion of imagery details a passage from Kate Chopin’s “Story of an Hour” and explains the effect. Bonus: OSU provides a video and also posts the discussion in Spanish.

Active vs Passive Voice

A sentence written in active voice has a subject that performs the action of the verb. For example: The dog bit the mailman. The dog performs the action of biting.

A sentence in passive voice has almost a backwards arrangement. The subject and direct object of the example sentence are flipped: The mailman was bitten by the dog. Here, the subject mailman is not performing the action of the verb. He is not doing the biting. Passive voice sentences usually contain “be” verbs and a prepositional phrase. Moreover, the brain has to slow down just a little bit to rearrange word order and decipher the meaning. However, passive voice can be preferred in specific situations, such as in scientific reports, an instance when the topic is most important and needs to fall in the subject position in a sentence: i.e., The gamma rays were dialed up to maximum force.

Active voice is much more direct. In the examples, “the dog / bit / the mailman” takes fewer words than “the mailman / was bitten / by / the dog.” If you want to speak authoritatively, clearly, and concisely, active voice is usually better. It is also easier for readers to follow precisely because it is direct. When you are trying to convey complex ideas, it is sometimes better to use active voice so that your sentence structure is simpler

Neither kind of sentence is “right” or “wrong”; they simply DO different things and one is often better suited to your purpose.

Helpful Resources

GCGLearnFree.org has posted an easy-to-follow Active vs. Passive video on YouTube: Active vs Passive Voice in Your Writing

Grammarly’s website details active and passive voice and suggests ways to switch passive to active: Writing in Active Voice

If you would rather listen to an explanation of active and passive voice, Mignon Fogarty, a. k. a. Grammar Girl, hosts a podcast that explains grammar topics in depth. Click here for her podcast on active voice.

Here’s a follow-up to Grammar Girl’s podcast on active voice.

Click here for Grammar Girl’s podcast on passive voice, which furthers a clearer understanding of active voice as well.

Point of View

“Point of view” refers to the perspective from which a speaker sees/speaks. It is a stylistic element because it affects the writers’ voice, their relationship to what they are writing, and their relationship with their reader.

- First-person point of view focuses on the writer. Examples include letters, emails, personal journals, expressions which center around the author. In these instances, pronouns such as the singular I, me, my, as well as the plural we, us, our indicate that the provided information ties directly to the person writing the text.

- Second-person point of view focuses on the audience. Examples include instructions or recommendations, expressions that center around the reader. In these instances, pronouns such as you and your direct the reader to take some type of action, such as: You should first open the jar of peanut butter. Another variant is the understood you, in which the “you” is never stated: First, open the jar of peanut butter.

- Third-person point of view focuses on the subject or other people. Examples include academic essays and articles. In these instances, pronouns such as he, she, they, it, his, her, their, its indicate a person or object that is being discussed.

POV is often related to genre. For example, traditionally, most researched articles are written in third person while autobiography is, of course, written in first person. Some scholarly disciplines, however, are beginning to embrace first-person because it acknowledges the truth that there is an invested human doing the research.