17 The Writing Process

What is the writing process?

Think of the writing process as a journey. First, you have a destination in mind, except that yours is something like “Research Paper” or “Literacy Narrative” instead of “Lulu’s Restaurant near Gulf Shores, Alabama.” Where do you begin? You may have heard this ancient proverb, often attributed to Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu: “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” From your first step, you take another step and another one, hopefully in the general direction of your destination.

With a sense of exploration, therefore, this chapter takes you through a commonly used set of writing steps, from “Understanding the Assignment” to “Revising.” You can undertake these steps in order, repeat some or all of them, or mix them up. After all, it’s your writing process.

That said, some novice and experienced writers find it useful to move sequentially at first: understanding the assignment, prewriting, planning, getting feedback, and revising. When a reporter first gets an assignment, for example, they will likely ask for details: When is the assignment due? What’s my target word count? What kind of story is it? That’s part of understanding the assignment. In a meeting with other reporters, they may talk about the assignment and brainstorm; those are prewriting activities. They’ll also research their topic and plan ahead before writing the piece. After submitting their article to an editor, they respond to feedback and revise before publication. The basic steps of the writing process, in short, are:

- Prewriting

- Planning

- Drafting

- Reading aloud

- Receiving feedback

- Understanding Feedback

- Revising

- Editing and proofreading

All of these steps are part of the writing process. Science-fiction writer Octavia Butler says, “Keep writing. Keep writing. It’s the old idea that behavior that gets rewarded tends to get repeated. If you stop writing, then you’re kind of rewarding yourself with not writing. If you keep writing, after a while your brain maybe gets the idea.” In other words, persist in your process, from planning to revising.

Another key point to remember is that writing is a social process through which you collaborate with others, indirectly and directly. Even though we may have an image in our mind of that perfect, mythical, genius writer who is alone in their studio while composing a masterpiece, writing is social. In other words, we do not write in isolation. Have you ever asked a friend to read a text-message before sending it? Have you ever been on the other side of that equation, giving feedback on a piece of writing? Perhaps you’ve been lost while trying to find a restaurant a friend recommended; did you use a map app for help? That app was created by people, and they’re helping you find your way. Writing takes place in social contexts, whether you’re asking for feedback, calling on the expertise of sources, or considering the best ways to connect with your audience.

One of the most rewarding steps in the writing process, therefore, is working with others. Although this step can be a little scary, sharing our writing with others can be rewarding. To take the plunge, Powell suggests that writers try to “Think about the confluence of voices. Hear that confluence. Enter it. Engage in it. Participate in it fully.” In other words, think about writing as a shared journey. While you will explore some parts of that journey on your own, there are key points along the way for collaborating with others.

Each chapter in this OER offers suggestions for working through the writing process to submit each major assignment. The following sections suggest a few other options for collaborative and individual steps, all of which are aimed at helping you navigate your own writing process. You can repeat, rearrange, and reimagine these steps as you need to. We have also included a variety of activities you can use to develop your own writing process.

Step 1: Understanding the Assignment

Though any writing process is a flexible one, clearly understanding the assignment expectations ensures that you avoid any potential missteps. It’s crucial, in other words, that you make sure you have a good sense of what the assignment requires you to do. Read the assignment carefully. Print a copy to mark up or highlight key words. Ask questions about it. That way, you’ll save time and stay on task. Of course, once you have a complete draft (congratulations!), that’s a good moment to revisit the assignment. Did you skip a key task or omit a required element? Or maybe you’re stuck halfway through and need to review the assignment? In any case, here are a few questions to guide you through this stage:

- What’s required of me in this assignment? For example, when is it due? How long should it be? And what genre is it?

- What other genre expectations exist? A research project, for instance, calls on you to spend significant time exploring the topic through credible sources, whereas a personal narrative relies on your personal experiences to tell a story. For these reasons, pay attention to the expectations outlined in the assignment.

- Is there a checklist for required elements or important steps? Use that checklist as you go through your writing process or create one of your own with target dates for completion.

- Have more questions? Check with classmates or ask your instructor to clarify.

Think of the assignment like a roadmap. To arrive at your destination, what do you need to do? What do you need to prepare, who can help you, and what do you need to do to reach the destination on time?

Step 2: Prewriting

As the name suggests, prewriting comes first. Brainstorming, listing, asking questions, freewriting, and looping are common activities at this stage, though you can use them at any point in your process. That is, you can repeat or retrace these steps at any point in your writing process. The goal is to take these first steps for your writing journey, like doing warm-up stretches before karate or yoga class.

Brainstorming

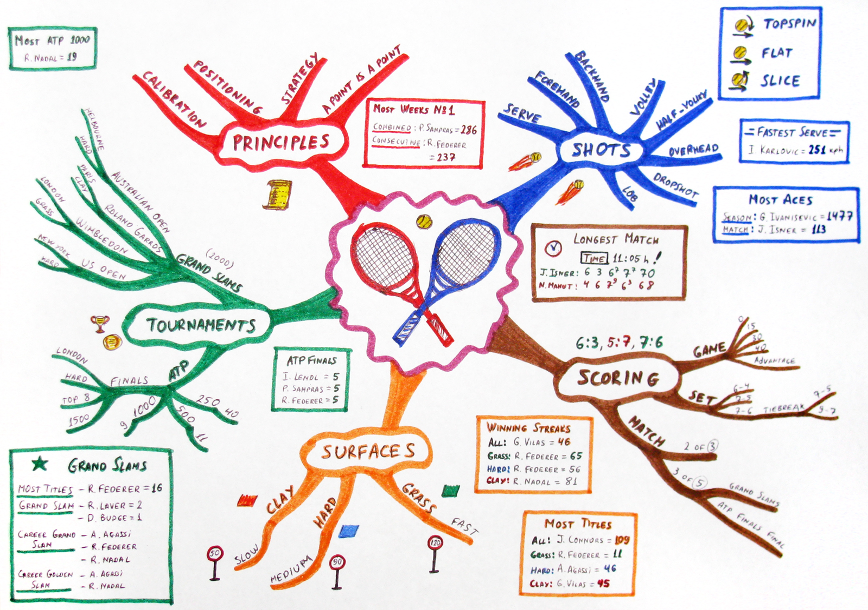

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines brainstorming as “the mulling over of ideas by one or more individuals in an attempt to devise or find a solution to a problem.” On your own or with a group, brainstorming means generating ideas informally and without the pressure of finding the “perfect” solution or direction. This activity takes a variety of forms for collecting the ideas you come up with: cluster maps, flow charts, Venn diagrams, and so forth. A few neat tools for these activities are MindMeister, Popplet, IdeaBoardz, SimpleMind (mobile app), and Ideament (mobile app), but there are plenty more to explore. Of course, there’s always your good ol’ paper and pen(cil) for jotting ideas on a whiteboard as they pop into your head or folks in your group share their ideas aloud.Whatever approach works for you, brainstorming is vital to the writing process because it helps get those gears turning and our thoughts organized.

Guess what else is neat about brainstorming? While it’s often pursued as a prewriting activity, you can brainstorm in the middle of your project or near the end, too, especially when we’re not sure where to go next or what to do. For instance, when we come across that ever so difficult and paralyzing feeling of writer’s block, guess what? Brainstorming can get us moving again. After all, writer-teacher Donald Murray says that writer’s block “is a natural and appropriate way to respond to a writing task or a new stage in the writing process” (1985, p. 44). In other words, it’s okay to get stuck. Take a deep breath and try brainstorming or another low-pressure activity, such as freewriting, clustering, or looping. In the same way the air typically feels fresher, clearer, and promising after a storm, after you brainstorm, your mind may feel refreshed, clear, and ready to get going and produce amazing ideas for writing again.

For a fun take on brainstorming, see this video, in which comedian and producer Bernie Mac talks about his creative process.

Listing

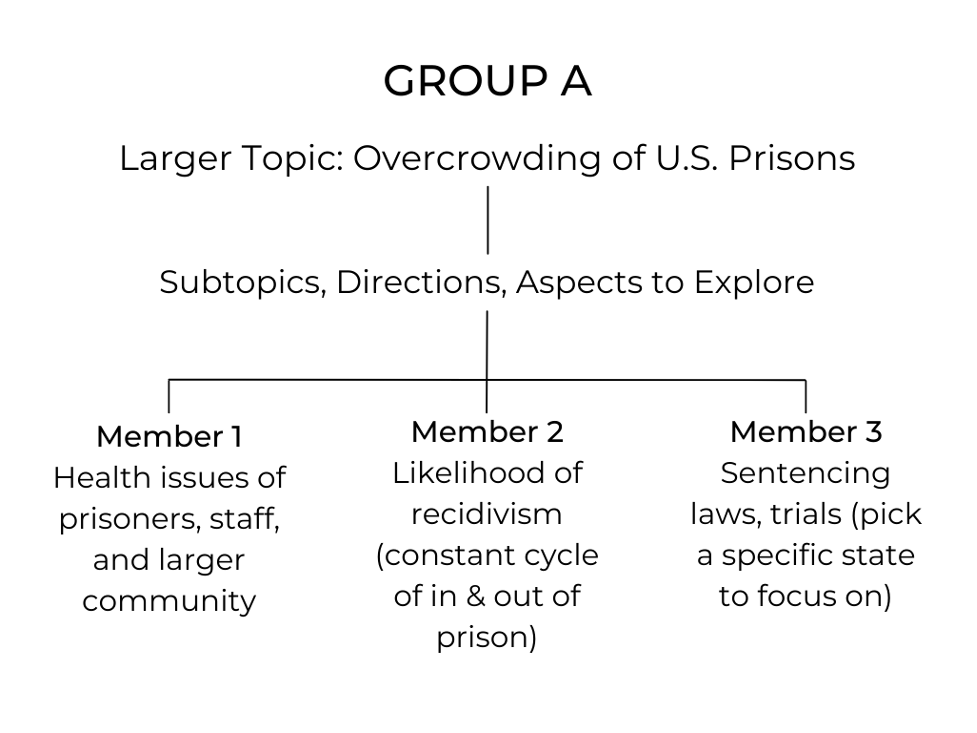

This activity is a kind of brainstorming in which you or your team list possible topics, examples, directions, and big ideas (little ones, too). Listing resembles outlining but is less formal and less structured than an outline might be. As with other activities in this section, the goal is to get your ideas flowing and to start writing.

Here’s a list about the Overcrowding of U.S. Prisons, done in a structured variation called a tree diagram or organization chart.

Freewriting and Freetalking

This activity is one of the most unstructured, because it entails writing without worrying about pesky grammar, perfect outlines, or great ideas for the direction of your paper. Freewriting is usually completed in short bursts and is most helpful after brainstorming or listing. For example, look at your brainstorming notes or lists. Then, for 5 minutes, 10 minutes, or 15 minutes, just write whatever comes to mind without judging, editing, or self-censoring what you’re writing.

You may also find it useful to try freetalking, which is free-association style talking, which happens when you think out loud, recording your thoughts in a brief audio recording or while talking with a classmate who takes notes on what you say. Whatever approach works for you, freewriting and freetalking don’t require solid directions or perfectly composed sentences; you’re just thinking through things. Do, however, pause periodically. Read what you’ve written so far,listen to what you recorded, or ask your listener to repeat back to you what they’ve heard you say. Pick out one good or intriguing sentence or idea; write it down and try the next activity.

Looping

What do you do when you get stuck in traffic? Look for alternative routes. When there are none (or the next exit is a mile away or more), perhaps you turn on some loud happy music for a calming brain-break. Like searching for alternative routes or switching to a low-stress activity, a useful technique in your writing repertoire could be looping, a focused or structured approach to freewriting. For example, here’s a useful exercise, adapted from The St. Martin’s Guide to Writing:

- On a piece of paper, in a new Google Doc, or wherever you prefer writing, jot down your topic or idea. Take a moment to read what you wrote.

- Set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes (your choice), and then write without stopping.

- When the timer goes off, stop!

- Read what you’ve written so far. Highlight or underline the best sentence, idea, or other point.

- On a new page, rewrite your topic/idea. Add one of the sentences or key points you marked in step 4.

- Set a timer and write nonstop again for 5 to 10 minutes.

- Repeat until you have a better sense of the direction you want to take next.

Asking questions

Another prewriting activity is asking questions. By creating questions and trying to answer them, you gain a strong sense of direction by engaging in inquiry which can be especially helpful because writing can be daunting. The questions to ask can vary from writing project to writing project, of course. Questions like these can help you prioritize directions and content.

For a research paper, you might ask:

- What do I know about my topic?

- What do I want/need to know about my topic?

- What does my audience want or need to know?

For a narrative essay, you might ask:

- What idea or event has been meaningful to me?

- What story might I want to tell about that meaningful idea or event?

- What story might I want to tell other people?

- What stories do I like to hear and why do they resonate with me?

- How can I tell a story my readers will be able to connect to?

Step 3: Planning/Outlining/Reverse Outlining

Do you like to plan your trip or just explore? Many writers like to plan their work before getting started. Like a roadmap, however, a writing plan doesn’t have to be an outline. Planning can take on the form of clustering, mind mapping, or flowcharting.

The two-part goal of these planning activities is 1) to get your ideas out of your head and into print, and 2) to launch you into the beginnings of a good plan, organization, sequence, or other kind of order. Whether you cluster or outline, all of these approaches work like a roadmap or list of places you’re going to visit with your audience so that they will, hopefully, arrive at the destination you have in mind.

For example, when you load an address into a map app, the program lays out a sequence of turns, distances, alternative routes, roadblocks, coffee shops, gas stations, and so forth. All of these places are, potentially, notable places on your way from point A to point Z. The map app also includes a “Start” button or “Begin Navigation” command. When you use voice navigation, the app gives vocal directions such as “In 400 feet, turn right on Main Street. Your destination will be on the left.”

That’s what plans do: They lay out the directions, distances, meaningful landmarks, and the end point. For writing, read on for a few common ways to plan your trip.

Clustering and Mind Maps

Some writers like to draw or sketch out their ideas. In clustering, for example, you write a key idea in the middle of a page; circle it; then fill the page with related ideas and words; circle each idea or word individually; and draw lines connecting new ideas to the original idea.

A similar visual approach is a mind map, which you can do by hand or complete with a digital application such as Mindly and Ayoa. Like clustering, flowcharting, and tree diagrams, mind maps help you discover connections between the ideas you have for your work. The following image depicts a mind/cluster map at work to help a writer organize and structure their report on tennis.

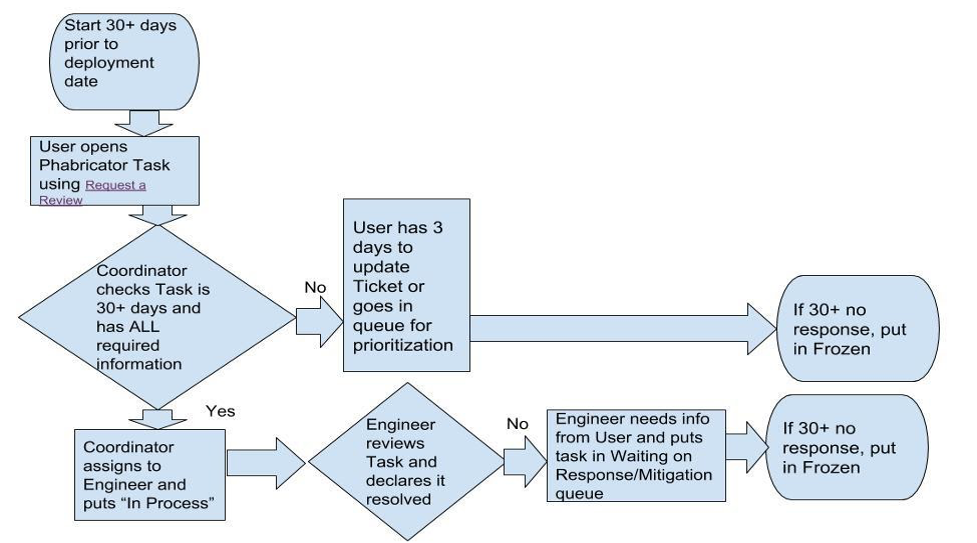

Flowcharts

This type of planning typically starts with a big idea or title or a simple “Start here!” From there, most flowcharts move through key topics or points as if you’re playing a board game. The last point on the chart shows the destination or conclusion. The example shown below displays the writer’s process for developing company policy. Notice how the writer moves through different stages and actions before coming to the final decision and action. Flowcharts can help you find direction and see how things fit together.

Outlining

More formal than the planning activities listed so far, outlines break your project into parts, levels, or sections: A, B, C, D, E or 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (or whatever ordering system you prefer, from bullet-point lists to stars). You can write out full sentences for each part or use short descriptions. A basic outline for this section, for example, was follows:

- Beginning

- Introduce planning

- Provide context

- Define terms

- Middle

- Clustering & mind mapping

- Flowcharting

- Outlining

- Conclusion

- Restate key points

- Provide closing guidance

From the basic 1-2-3 or beginning-middle-conclusion approach, start filling in the details. What do you need to do in the beginning? Typically, introduce your topic and, if possible, state your key point or argument (often called the thesis statement). In the middle, it’s common to provide several examples or other forms of evidence that support your point. In the ending, you need to sum up those points, tie everything together, or come to the resolution of the story. By the way, some writers use full sentences in their outlines; others break the plan into bullet points. It’s up to you!

As we’ve explored here, there are so many ways to plan your writing project, from clustering to outlining. Each approach prepares you for the work ahead, helping you plot your course, manage your time, gather information, and start writing your first drafts. Another key point is that at any planning stage (and any point in your writing process, really), writers often return to the brainstorming step or sidetrack to do more research or revise their outline. Remember, too, that the writing process is recursive; it’s okay to mix-and-match your way through the work. Therefore, feel free to return to any of these planning steps as needed. Also, if you sense that your plan isn’t working, try reverse outlining. Once you’ve launched forward with your work, keep moving.

Reverse Outlining

This process is what it sounds like: outlining in reverse. That is, after writing (not before), you will outline the structure of your draft. For initial or prewriting outlines, you create them early in the writing process to organize ideas and set up your structure. Outlines are plans. With reverse outlining, you take a written draft and break it down into sections or parts, identifying main parts and key moves. Your goal is to find out if the structure functions in the way you intended it to function. Did you stick to the original plan or outline? Did you digress or take some new directions?

Reverse outlining can help you visualize what you did and then decide if more changes need to be made.

When reverse outlining, there isn’t a right or a wrong way to go about it, but you might consider two different approaches that follow below. In the embedded video, you’ll see how a writer can extract information from their paper to create an outline that closely mirrors the standard outline format.

Step 4: Drafting

Once you have done your thoughtwork and planning, it is time to start drafting (unless you’re an excessive pre-writer who already started drafting). Here is the most important thing we can say about drafting: JUST DO IT. Get your ideas on the page in a reasonably legible order. Get some words and sentences out there. You can revise later. You can make it “good” later.

Take a deep breath. Focus. Maybe turn on some energetic ambient music. And write.

Step 5: Revising

Even the most experienced, successful writers may cringe a little at this stage in the process. But there are good reasons to enjoy it, or at least, embrace it. First and foremost is that the revision stage means you’ve written something; now it just needs polishing. To get started, think of it as re-vision—literally, seeing your piece again from a different angle. That is, in revision, you reimagine your work and its potential. Consider the following questions, which can help guide and focus your revision, especially if you get stuck and aren’t sure how to move forward.

- What new information can you discover as you revise?

- How can you add new information to what you’ve already written?

- What challenges did you encounter, and how might you respond to those challenges in writing to strengthen the piece?

- What linguistic, rhetorical, design, or other devices can you experiment with to impress and engage your reader?

Before you can ask these questions, however, you need to have written your first draft; you need something substantive to work with. As Jodi Picoult, a successful American novelist, says, “You can’t edit a blank page” (Kramer). Another writer, Anne Lamott, reminds us that early drafts aren’t perfect. These points are both spot-on. You need a working draft for revision, even if that draft is far from perfect.

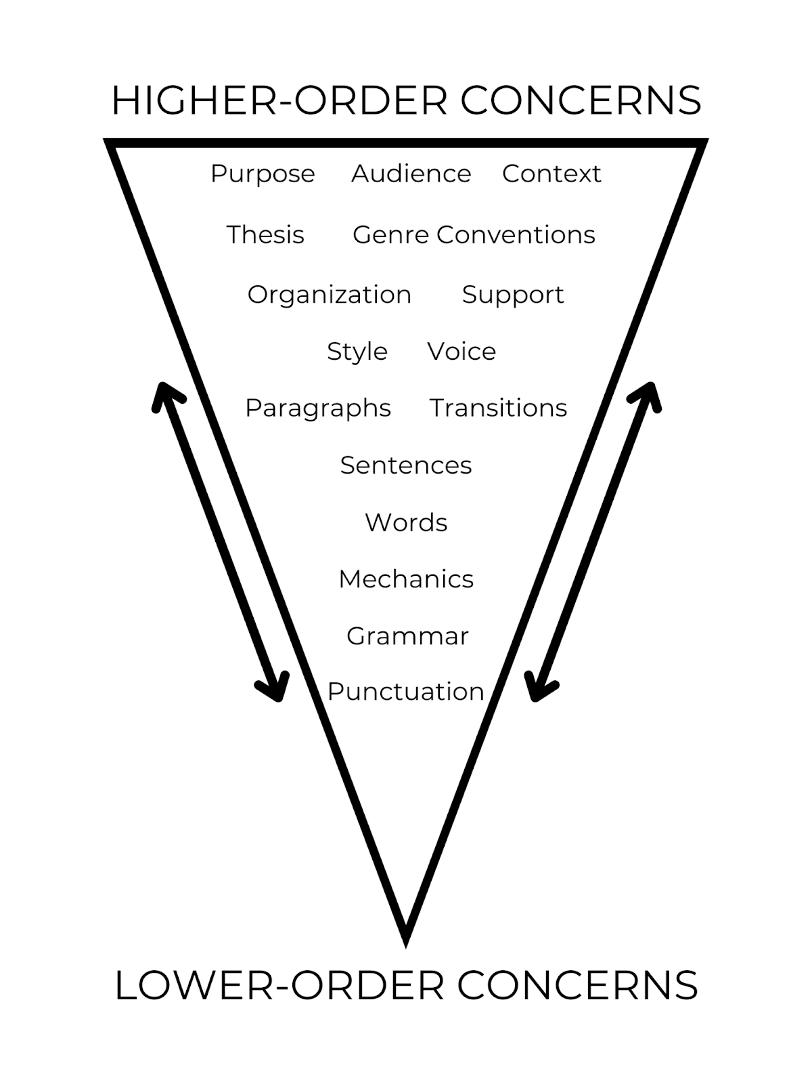

Furthermore, revision is more than just editing or proofreading; revision requires critical thinking, feedback, and a careful examination of our work. Note that we said examination. Revision is not a quick scan of your work for errors like comma problems, misspelled words, or other low-order concerns (LOCs). That’s editing and proofreading. Revision means looking at your work as a whole, taking notes of all its parts, their overall effectiveness, and other HOCs.

Revision, in other words, means examining such concerns as organization, argument/thesis, purpose, audience, and supporting evidence. It is difficult, if not impossible, to revise without considering these components, which we call higher-order concerns (HOCs) because these components have a bigger impact on the overall effectiveness of any composition. Lower-order concerns or LOCs, on the other hand, affect the overall appearance, polish, and clarity of the composition.

In this chart, the most significant HOCs are purpose, audience, and context; as outlined in the chapter on rhetoric, these three form the rhetorical situation. It’s critical to make sure these elements (purpose, audience, and context) are clear and effective. Of nearly equal importance are the thesis or argument and genre conventions.

To consider these concepts in action, imagine you’ve written a visual analysis, and you’re trying to decide which HOCs to prioritize. In the visual-analysis genre, a reader would expect to read 1) a description of the artifact you’re analyzing; 2) a clear identification of its key components; 3) a detailed description of how those key components work together to accomplish the overall purpose and message of the visual; and 4) an evaluation of whether those components work well or not and why or why not. Therefore, when you start revising, step back and think about a) your purpose, which is to breakdown the components to properly evaluate the visual; b) the artifact’s intended audience as well as the audience you’re relaying your analysis to; and c) the artifact’s context and the setting for your analysis. These are all HOCs. If your HOCs are all aligned with the purpose of your piece of writing, then you may be close to finished with revising. If not, then you may need to revise further.

Revision, therefore, is an important stage in the writing process. It takes time and persistence. If revising feels like an extra step that you don’t have time for, take a cue from the best writers. Professional writers, for example, understand that developing good revision habits will strengthen their communication skills in the long term and for each individual project. Therefore, they budget their time to allow for revising. With practice, revising gets easier. Furthermore, remember that writing is a recursive process; you can revisit earlier steps in your process before, during, and after revising. In the end, however, revision helps us develop effective writing habits. Revision also helps us understand ourselves as writers and communicators by providing an opportunity to reflect on our purpose in writing how well we achieve our purpose. Therefore, plan to make revision a central part of your writing process every time you write.

Reading Aloud

In Beijing in 2005, a young woman became known for standing next to a main road during rush hour, opening a book, and reading out loud. She told a journalist writing for The New York Times that reading out loud helped her concentrate while practicing her spoken English. At the time of the report, she had been reading aloud at the busy intersection for at least five years.

Of course, you don’t have to stand beside a busy intersection to get the benefits of reading aloud. Like reverse outlining, this revision strategy helps you step back from your work, to hear it in a new way, and to become your own audience. Reading aloud works just as well if you ask someone else to read your work aloud. Teacher-writer Donald Murray suggests, “Read a draft aloud to hear the voice—when it is most effective and when it is not. Have someone read the draft to you so you can hear its voice.” We often have a better sense of grammar, mechanics, and style in the spoken word than for words on a page or screen.

If asking someone else to read your work back to you feels a little intimidating, you might try using a screen reader or asking a trusted classmate, co-worker, friend, teacher, or family member to read your paper to you while you take notes on what you’d like to revise later. After another person has read your work to you, ask them to summarize it for you. This step helps you know if you’re getting your point across. Ask them if they think you need to tweak some aspect of the work, such as fixing a mechanical problem, choosing a better word, or dropping a section that detours from the main point. In other words, have a conversation with your reader and, from there, improve what you’ve written. For more on this step, revisit some of the suggestions in the peer-review section.

Ready to read aloud? Find a comfy place, gather your writing, and read a sentence, paragraph, or one page out loud. What do you notice?

Peer Review

Earlier in this chapter, we noted that writing is an inherently social process. You may feel alone while writing, but in fact, you “are carried on the backs of all the writers who came before [you]” (Goldberg 79). You draw on the ideas others have put out there, in other words. You might borrow a phrase here, summarize an idea there, put it all back together in a way unique to you, but you are part of something bigger than yourself. In newsrooms, social clubs, nonprofit organizations, Fortune 500 companies, it’s also standard practice to talk with or request feedback from someone else about your project so that you receive the most helpful suggestions for moving forward with the project.

For a writing class, that’s what peer-review is: sharing your composition with a fellow writer or group of fellow writers, receiving constructive feedback, and using that feedback to revise your work. Peer review, of course, is a bit more structured than talking about your project informally (though that step is very useful). For example, here’s the CARES approach to peer review, originally developed by The Online Writing Lab at Excelsior College:

CARES Peer Review

C: Congratulate. What does the writer do well? List one or more aspects.

A: Ask questions, especially about any parts that were confusing or about places where you need clarification about the thesis or main point. Follow those questions with specific suggestions (3 or fewer).

R: Request more information, details, context, etc. What else would you like to know about the topic that can enhance the essay and that supports the thesis? Would additional information be useful?

E: Evaluate the composition. That is, consider what specific detail(s) do or do not work or can be moved within the essay?

S: Summarize. Overall, what new information have you learned or how are you thinking differently after this reading?

The sharing process will help you continue writing or get you back on track. Also, keep in mind that it’s common to worry that peer review is not as beneficial as feedback from a mentor or teacher, and that many of us are shy about sharing our work. However, a major part of the writing process is thinking. Our peers can help us advance and enhance our inquiry processes.

When asking for feedback, for example, provide your readers with questions to answer about your writing. The more you can assist them in focusing on specific components of your writing that shape its reception, message, and success, the more targeted, constructive, and productive your feedback will be. Being specific about what kind of feedback you want can also help you and your peers overcome feelings of uncertainty about how to review someone else’s writing. To guide reviewers, here’s one set of questions, adapted from Emilie Zickel’s “Peer Review and Responding to Others’ Drafts.”

- What is the writer’s main point? State it or summarize it.

- What evidence (information, data, or examples) does the writer provide to support this main point?

- Is the writer consistently working toward achieving the assignment’s purpose? Why or why not?

- Describe the tone of the draft? Friendly? Authoritative? Lecturing? Humorous or sarcastic? Consider the intended audience of the draft: is this tone appropriate, persuasive, or otherwise effective?

As you can see, there are several approaches to peer review. All of them lead to skills you can take with you beyond the classroom because they require effective collaboration. Peer review, furthermore, provides new insight with regard to your work. Effective collaboration is so important, in fact, that you’ll find yourself using it in many future contexts as a writer, a working professional, and even as a community member.

Understanding Feedback

With intentional collaborations like peer review, tutoring sessions, and instructor feedback, you receive direct and immediate feedback. But once you’ve participated in one or more of these activities, what do you do next? How do you use feedback to move forward with your project?

First, you’ll want to keep in mind the intention of feedback and prioritize the feedback you’ve been given. Remember that feedback is intended to improve your work. Therefore, in the spirit of collaboration, accept feedback with an open mind, and give feedback in a way that helps other writers grow. Second, consider any higher-order concerns (HOCs) identified by your instructor, tutor, or peer reviewer; HOCs are the most complex, substantive, in-depth aspects of your work, such as organization, argument or thesis statement, purpose, audience, and supporting evidence; lower-order concerns (LOCs) are important but not as critical as HOCs in conveying a message or deeper meaning to a reader. LOCs often include mechanics, spelling, grammar, and punctuation; we’ll come back to HOCs and LOCs more fully in the next section. Third, think about how you can address these concerns. For example, here are a few ways to respond to feedback:

- Review the feedback carefully.

- If you don’t understand a point, ask your reviewer to clarify.

- Divide the feedback or comments into HOCs and LOCs.

- Prioritize which HOCs and LOCs will guide your revision process. Which are most important? (Hint: it’s usually the HOCs!)

- Start with the most important concern, and from there, work your way through the feedback—from HOCs to LOCs.

- Double-check the assignment sheet, rubric, or other guidelines you’ve received. These instructional documents can help you prioritize what you need to do. Can you match feedback or comments to points on the rubric or assignment sheet?

- Look for positive feedback. What did you do well?

- Thinking ahead to your next composition—whether that takes place in a writing classroom, on the job, or in another situation—consider what feedback will be most helpful to you becoming a better writer in the long term?

As a final step, ask for help as you work through the feedback process. If the feedback comes from your instructor, for example, you might find it helpful to do your best to work through the steps above, then schedule a session with your institution’s writing center. Or invite peer reviewers to a writing group in which you work together to understand feedback and come up with ways to successfully implement that feedback

Feedback is useful at any stage. Got an outline but haven’t written much? Seek feedback. Have a title and introduction but not much else? Feedback from a friend could be your solution. One last thought: Give your reviewers time, too; it’s unrealistic to expect detailed feedback moments before a project is due.

Reflections & Cover Letters

Your instructor will likely ask you to reflect on your writing and writing processes for your major assignments. This is part of the writing process as it helps us understand what we learned, what we felt, what we might do differently next time, and what we are proud of ourselves for. Most simply, reflection is the process of seeing something from a new perspective, like stepping back and looking in a mirror. Reflections on writing, in particular, are metacognitive processes in which you look back in order to look forward, as if the mirror were a time machine and you were a time traveler. Metacognition is, most simply, thinking about thinking. Written reflections, therefore, present an opportunity for writing about writing. Writers’ reflections can be styled as essays, posted as videos or podcasts, submitted to discussion boards, or included in the body of a cover letter that introduces or contextualizes your project.

Think of it this way: Someone picking up a basketball for the first time might make a 3-point shot without thinking about it or having any technique whatsoever; but someone aiming to play for the WNBA or NBA is going to analyze their form, study successful players, practice a lot, and look at video of themselves shooting baskets in order to reflect on their technique. In short, they’re going to go “meta” or metacognitive as they improve to make more than a single lucky shot.

Cover letters (also referred to as reflection letters) are often written as short essays or letters to the reader to contextualize the writer’s work and their process (that is, they approached or understand their most recent writing process in relation to previous and possibly future ones; they also show what steps were taken to produce the project).

For writing reflections or cover letters, your instructor might ask you to answer questions, such as:

- When you started this project, what did you do? Describe how or why you picked this topic, approach, or argument.

- What challenged you along the way? How did you respond to or overcome these challenges?

- On the other hand, what about your writing process felt easy for you and why?

- What rhetorical choices did you make and why? Perhaps you chose an informal style; why? What examples or elements from the artifact, narrative, or research did you choose to include and what did you leave out? Who was your audience? What did you assume they knew or did not know?

- What strategies worked best in your writing process and/or in the final version of the project? Consider how your drafts, notes, outlines, or other steps fit together as a whole.

- What would you do differently for future projects and why?

Such questions can be helpful at almost any stage of your writing process. Reflections, in short, help you become a better writer. For example, when many writers feel stuck at any point in the process, they ask themselves questions, such as: “What am I missing? Did I get my main point across? Are there any phrases, sentences, paragraphs, or sections that work well? Are there any parts that need further development?” Some of these reflective questions point toward revision (another stage in the writing process). When the project is finished or nearly complete, however, a new set of questions may be useful, especially in helping you do better next time, such as: “What part of my writing process was most effective or least effective, and why do I think that was so? What aspect of my writing process might be useful to other composing situations?”

Okay, that’s a lot to think about (but reflection is about thinking). Here are a few ideas for synthesizing your answers into a shareable form:

- Style your reflection as a letter. That is, begin with a salutation to an anonymous reader (To whom it may concern . . . Dear instructor . . . Dear committee members . . . or Dear me). Many writers feel most comfortable with this approach, which is one reason why instructors often blend reflection with cover letters.

- Introduce and contextualize your work. In other words, try to answer as many of the above questions as you can.

- Analyze your composition processes. That is, critically reflect on the steps and strategies you used in planning, drafting, composing, and revising. As you engaged in this process, for example, how did you incorporate feedback? If so, how? If not, why not?

- Reflect on your overall development as a writer. Can you describe any moments of insight or breakthroughs that occurred for you this semester as you composed this text and later ones?

- Articulate your learning. That is, be specific. Spell it out. What exactly did you learn in this class that you can use in future courses, in your career, in other writing situations, and in your day-to-day life?

- Discuss the challenges you faced during the writing process. How did you address those challenges, and how you might apply these skills and knowledge in the future? Project forward. For your next writing project, how can you use what you’ve learned? Can you transfer this knowledge to other composing situations, in or out of the classroom?

Before we finish this section, consider cover letters again. We’ve noted that writer reflections can be styled in a variety of ways, including as a letter. This approach often makes reflections easier to do because you’re working through the questions above and explaining them to someone else. (Remember Yancey’s comment about how useful this exercise is.) Here’s an excerpt from such a letter:

Dear [Instructor],

… I chose my discourse community essay because of what this [life story] meant to me. I was eager to brainstorm ideas of how I could best represent my feelings and my story. …After sorting through nearly 10 years’ worth of medals, score sheets, programs, leotards, and pictures, I could start showing my story. My goal was to not spend any money and use all my resources from home, which I achieved. I took a box and cut the sides to display the inside where I put all my artifacts. … Oddly, my trouble came with condensing my career into one trifold. … I needed to narrow down my selection [then] struggled with trying to fill the space left [on the poster] but then I had a thought … The emptiness reflects [that] all I knew growing up was to focus on my training and school. …

— excerpt from “Growing Up a Future Olympian: The Remix”

Originally published in the 2020-2021 FYC eReader

In this example, it’s clear how the writer pondered reflective questions, such as describing how she got started with the project and how she addressed challenges. In written reflections, says teacher-scholar Kathleen B. Yancey, “we learn to understand ourselves through explaining ourselves to others.” That’s metacognition in action, and it can help you become a better writer at any stage of your process.

Repeating & Learning

Remember: You can backtrack, sidetrack, and get back on track at any point during the writing process. It’s also okay to skip ahead; many writers jump to working on their conclusions, then return to the introduction later. An option, therefore, is to return to, or skip ahead to, any other step in the writing process when needed. Once you’ve completed a first draft, for example, ask yourself a few questions. Would a fresh round of brainstorming help? Is it a good time to talk about your work with a colleague or read passages aloud? Perhaps you need more information from other sources or need to read a model essay in the genre. Of course, you may need a break from writing (which we all do at times). Maybe you need feedback on what you’ve done (or thought about) so far. Just remember to come back and do what Butler said: “Keep writing.” And guess what? All the activities we’ve discussed so far are writing.

Remember: You can backtrack, sidetrack, and get back on track at any point during the writing process. It’s also okay to skip ahead; many writers jump to working on their conclusions, then return to the introduction later. An option, therefore, is to return to, or skip ahead to, any other step in the writing process when needed. Once you’ve completed a first draft, for example, ask yourself a few questions. Would a fresh round of brainstorming help? Is it a good time to talk about your work with a colleague or read passages aloud? Perhaps you need more information from other sources or need to read a model essay in the genre. Of course, you may need a break from writing (which we all do at times). Maybe you need feedback on what you’ve done (or thought about) so far. Just remember to come back and do what Butler said: “Keep writing.” And guess what? All the activities we’ve discussed so far are writing.

There’s one other possible step here, of course: If you’re truly stuck, the project just isn’t going the way you want it to, or it feels as if you’ve hit a dead end, even the most experienced writers will scrap what they’ve written to start over. Have you ever started a road trip and decided you didn’t want to go to, say, Main Street after all? Dead ends happen in writing, too. We highly recommend, however, that you talk with your instructor if you hit such a road block.

As we conclude this chapter, remember that writing is a recursive process. It’s a set of steps or stages that you can work through, repeat, and adjust as you go, in other words. Also, Goldberg urges us to “trust the process.” That is, try the steps outlined in each section of this chapter. At first, you may find it helpful to try the steps in order, from understanding the assignment to revising, but later when you’re more comfortable with these steps, repeat some or all of the steps as needed or skip around. As we said at the beginning of this chapter, discover what works for you.

And give the process time to work by giving yourself time to do the work. You are not going to produce your best work by waiting until the last minute to write a 1,000-word essay or produce a 5-minute video. Even reporters, who are trained to write fast and efficiently, build time into their routines. They recognize that, even when they find “the flow,” writing takes real time. The more challenging the project, the more time the writing process will take. The more you have going on in life, school, or work, the more time you may need.

Exercise: Prewriting & Reflecting on Process

The following is a reflective exercise that blends freewriting, listing, and reflecting. Grab your writing tools (pen and paper, laptop, or smart tablet) and get ready to write. Your answers can be as long as you like. There’s no limit on how much you can freewrite in one sitting, but you will want to:

- In your own words, describe how writing is a process. There’s no need to worry about grammar and neat organization; just write whatever comes to mind.

- Next, list as many stages of that process as you can. Again, write without worrying about creating a perfect list. Any list will work.

- Finally, think about your writing process. Which of the writing process steps explained in this chapter do you use all the time? Are there any that you have never used or rarely use? Why?

- Thinking ahead, what strategies will you use for your next writing assignment? What would be new or exciting to try? What strategies don’t appeal to you and why?

Attributions

“Processes Flowchart,” CPortero (WMF), CC-SA 4.0, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Processes_Flowchart.jpg.

“Tennis mind map,” http://mindmapping.bg, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tennis-mindmap.png.

“Reverse outlining,” M. Babin et al., The Word on College Reading and Writing, , CC-BY-NC 4.0 International, https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/chapter/reverse-outlining/.

“Reverse Outlines” from UNC Chapel Hill Writing Center.

“Discussion: CARES Peer Review,” LibreTexts, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0, 6 Dec. 2020, https://human.libretexts.org/@go/page/58356.

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First Year Writing, Gagich, Melanie, and Emilie Zickel., CC-BY 4.0.

West, Deanna. “Growing Up A Future Olympian: The Remix,” 2020-2021 FYC eReader, Texas Woman’s University, eds. Justin Cook and Margaret Williams, 2021, pp. 111-114, CC-BY.