5 Finding & Evaluating Sources

In this chapter, we will practice:

- understanding types of sources and the information/perspectives they offer

- finding sources and generating search terms

- evaluating sources and considering ways we can use them

- thinking about bias in search engines

- recognizing fake news

Many first-time-in-college students grew up with Google close at hand. Have a question? Ask the internet and thousands of algorithms and bots will be at your fingertips, prepared to provide potential answers.

Being able to discern between reliable and unreliable sources is a skill called information literacy, and developing this skill in your writing classes will serve you well as you advance in your coursework. College writing instructors expect you to provide high-quality research to support arguments you make in your writing because you have access to library catalogs and databases overflowing with peer-reviewed, vetted information. This chapter will also help you sift through popular sources, consider their credibility and bias, and decide whether or not they are useful to you.

College-level writing often begins with a research question you want to answer and a charge to find a variety of sources to help you adequately answer your question. Writing about sources helps us process their information, their relationships, and the knowledge they hold all-together.

Types of Sources

Primary Sources

Ready to gather sources for your research paper or report? Great! Depending on the genre you’re writing in or your audience’s expectations, you may need to look at both primary and secondary sources. But, what are primary and secondary sources?

Primary sources are those sources we rely on for firsthand information i.e. written by someone who saw or experienced an event. The information contained in primary sources is sometimes unedited, meaning it is in its original form and hasn’t been proofread or revised by another person yet. Any type of information that is original and uninterpreted is a primary source.

Some examples of primary sources might include:

- Artifacts (e.g. coins, plant specimens, fossils, furniture, tools, clothing, all from the time under study)

- Audio recordings (e.g. radio programs)

- Diaries and letters

- Social media posts

- YouTube Videos

- Comments sections

- Interviews

- Autobiographies

- Newspaper articles written at the time an event occurred

- Original Documents (i.e. birth certificate, will, marriage license, trial transcript)

- Patents

- Blogs

- Photographs

- Proceedings of Meetings, conferences and symposia

- Records of organizations, government agencies (e.g. annual report, treaty, constitution, government document)

- Speeches

- Survey Research (e.g., market surveys, public opinion polls)

- Works of art, architecture, literature, and music (e.g., paintings, sculptures, musical scores, buildings, novels, poems)

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources differ from primary sources in that they are not original or firsthand accounts; they come to us secondhand. Oftentimes, they describe a thing based on other sources. Secondary sources use primary sources and build on them through analysis, interpretation, commentary, and criticism. In fact, your research paper will ultimately be a secondary source. Examples of secondary sources might include:

- Biographical works

- Commentaries, criticisms

- Dictionaries

- Histories

- Scholarly journal articles (can be primary depending on the discipline )

- Magazine and newspaper articles (this distinction varies by discipline)

- Monographs, other than fiction and autobiography

- Textbooks

- Encyclopedias

You might also find this table comparing types of primary versus secondary sources helpful.

Subject |

Primary Source Example |

Secondary Source Example |

| Art and Architecture | Painting by Van Gogh | Article critiquing an art piece |

| Sciences | Einstein’s diary | Biography written about Einstein |

| Humanities | Letters written by Martin Luther King Jr. | Website about Martin Luther King’s life |

| Social Sciences | Personal field journal of anthropologist Clifford Geertz | Magazine article about Clifford Geertz’s work |

| Performing Arts | Casablanca—film from 1942 | Biography of Casablanca director, Michael Curtiz |

Scholarly, Popular, and Trade Sources

Another important part of gathering and evaluating sources for research projects is knowing the difference between popular, scholarly, and trade publications.

- Popular magazine articles are typically written by journalists to entertain or inform a general audience,

- Scholarly articles are written by researchers or experts in a particular field. They use specialized vocabulary, have extensive citations, and are often peer-reviewed.

- Trade publications may be written by experts in a certain industry, but they are not considered scholarly, as they share general news, trends, and opinions, rather than advanced research, and are not peer-reviewed.

The physical appearance of print sources can help you identify the type of source as well. Popular magazines and trade publications are usually glossy with many photos. Scholarly journals are usually smaller and thicker with plain covers and images, In electronic sources you can check for bibliographies and author credentials or affiliations as potential indicators of scholarly sources.

| Scholarly | Popular | Trade | |

| Content | Research results/reports; reviews of research (review articles); book reviews | Current events; general interest articles | Articles about a certain business or industry |

| Purpose | To share research or scholarship with the academic community | To inform, entertain, or elicit an emotional response | To inform about business or industry news, trends, or products |

| Author | Scholars/researchers | Staff writers, journalists, freelancers | Staff writers, business/industry professionals |

| Audience(s) | Scholars, researchers, students | Communities within the general public | Business/industry professionals |

| Review | Editorial board made up of other scholars and researchers. Some articles are peer-reviewed | Staff editor | Staff editor |

| Citations | Bibliographies, references, endnotes, footnotes | May not have citations, or may be informal (ex. according to… or links) | Few, may or may not have any |

| Frequency | Quarterly or semi-annually | Weekly/monthly | Weekly/monthly |

| Ads | Minimal, usually only for scholarly products like books | Numerous ads for a variety of products | Ads are for products geared toward specific industry |

| Examples | Journal of Southern History; Developmental Psychology; American Literature; New England Journal of Medicine | Time; Vogue; Rolling Stone; New Yorker | Pharmacy Times; Oil and Gas Investor Magazine |

Finding Sources

In the Information Age, we have access to an overwhelming amount of information. Where should we even begin to look for answers to our questions? A quick internet search brings back more information than we can possibly read or understand in a lifetime. Because these results are usually ranked by relevance to our search terms, the first results are often the ones we spend the most time with. But these results are affected by our location, previous searches, and maybe even our social media activity. We probably never get a truly objective list of results, and realizing this is an important aspect of information evaluation. We will discuss some aspects of evaluating information in the next section, but for now it is useful to realize that all information is situated in relation to other information.on the internet

Popular search engines which contain scholarly sources include Science Direct, Microsoft Academic, WorldWideScience, ResearchGate, PubMed, JSTOR, Academic Search Premier, and OneSearch. These websites provide thousands of scholarly sources based on various subject areas.

A note about Google searching: a regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. You can use these sources to gather information, but it is important to identify clearly what kind of information they are offering, who is writing them and why, and what their claims are based on. You can also use Google Scholar to locate scholarly sources.

About Wikipedia: Wikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes useful references to scholarly articles at the bottom of the page. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in a more specific database.

at the library

Library databases and collections are powerful research tools. Use them to get scholarly information and sources on your topic. To effectively use library databases, start by understanding your research topic and identifying relevant keywords. Next, access your library’s database platform, often available through their website. Utilize the database’s search features, including “Advanced Search Options” to refine your results. If you get stuck, remember that librarians are the nicest and most helpful people in the world! You can call, email, or set up an appointment with them and they will guide you.

When using library databases, the following tips and links to UCLA’s Library website will help you:

- Choose the right database

- Select useful search words (scroll to the bottom of the page for two great videos)

- Use common advanced search techniques

- Have a plan when you have too many or too few search results

- Actually get the full-text of the articles you find

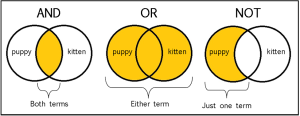

One common tool you can use when searching in databases is “Boolean logic,” which borrows from the work of 19th-century Irish mathematician George Boole. The idea is that terms can be connected with “Boolean operators” to control the kinds of results that come back to you from a set of organized information. The most common of these, and perhaps the most useful, are words you use every day: AND, OR, and NOT.

One common tool you can use when searching in databases is “Boolean logic,” which borrows from the work of 19th-century Irish mathematician George Boole. The idea is that terms can be connected with “Boolean operators” to control the kinds of results that come back to you from a set of organized information. The most common of these, and perhaps the most useful, are words you use every day: AND, OR, and NOT.

The “AND” operator works by requiring that two terms appear together. Searching “dogs AND cats” would return articles that contain the terms “dogs” and “cats.” If an article contained the term “dogs” but not “cats,” it would be excluded from the return.

The “OR” operator returns articles with either term. Searching “dogs OR cats” would return articles about dogs or cats even if the articles do not contain both terms.

The “NOT” operator excludes the second term. Searching “dogs NOT cats” will only return articles that mention dogs. Articles mentioning cats will be excluded.

By using the Boolean operators and quotation marks, you can really control your searches more carefully so that you end up with more of what you may need for your projects. Look at this example, which uses puppies and kittens to illustrate Boolean operators.

In the AND diagram, your search would return results only if they included both puppy and kitten. The OR diagram shows that either term individually, or both together would satisfy the search—this strategy would result in articles with the term puppy, kitten, and articles including both terms. NOT, in this example, excludes kitten. In the NOT diagram, results are only returned if they contain the term puppy, excluding results for kitten even if puppy is present in that same article.

Quotation marks are also very useful in searches. Most databases and web search engines recognize quotation marks to mean that the terms within them must appear all together. For example, the phrase “pumpkin spice coffee,” when placed in quotation marks, tells the search engine to treat the three words as one phrase. Only results containing the exact phrase as it appears in the quotation marks should be returned. An article that mentions pumpkin spice cakes (but not “pumpkin spice coffee”) would be excluded from this search.Type your textbox content here.

Practice: Finding Primary vs. Secondary Sources

Now that you know how to distinguish between primary and secondary sources, it’s time to locate one of each type of source related to your research topic.

Open up a Google Doc or a Microsoft Word document, and complete the following steps:

- Provide a link to each source type. If your source does not have a link, you can take a picture of it and insert the picture into your file or provide a thorough description of the source.

- Write a sentence or two for each source indicating what makes it either a primary or a secondary source.

- Count how many primary versus secondary sources you have, tallying those at the top of the page.

- Ask yourself, “Do I need more primary or secondary sources? What will my audience expect me to have?”

Based on how you answer these questions, you’ll have a better sense of whether or not the sources you’ve collected are supporting your research plan or goals. Talk with your instructor if you’re unsure how to proceed after evaluating the sources you have.

Evaluating Sources

Once you have found sources that seem relevant to your research question, it’s time to evaluate them. Evaluation is a process for determining the value or quality of what you have found. There are many different aspects involved in evaluating information, including whether the information is factually accurate, is certified by a person of authority, is recent or current, and whether it is relevant to your project.

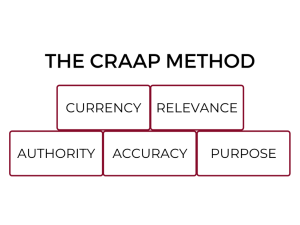

Let’s look at one approach to help us work through questions of evaluation, the CRAAP Method, which was developed by Librarian Sarah Blakeslee of the Meriam Library (University of California, Chico) in 2004. As a catchy acronym to help us evaluate information, the CRAAP Method stands for currency, relevancy, authority, accuracy, and purpose. Consider these definitions and questions when evaluating your sources:

Currency: the timeliness of the information.

-

- When was the information published or posted?

- What events or circumstances does it respond to or reflect?

- Has understanding of the topic or event shifted since it was published? Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does your topic require more current information, or will older sources work?

- Are the links functional?

- What other sources does it respond to or reflect?

Relevance: the importance of the information for your needs.

-

- Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for your needs)?

- Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining this is one you will use?

- Would you be comfortable citing this source in your research paper?

Authority: the source of the information.

-

- Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations? What are their investments?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source? Does the domain type tell us anything about the authority of the source (e.g. .com .edu .gov .org .net)?

Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness and correctness of the content.

-

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or referenced?

- Are there other sources or existing information or do you have personal knowledge that supports the authors claims?

- Is the language exaggerated or derogatory?

- Does the author present others’ perspectives to offer nuance?

- Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors?

Purpose: The reason the information exists.

-

- What do you think is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade? Remember, a text can have multiple purposes.

- Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Does the point of view appear to be objective and impartial in that it offers multiple perspectives and information from a wide variety of sources?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases in the text? Remember, these do not make the source “bad” or “inaccurate” or “unusable,” but we must be aware of these positions so that we can better understand the source’s information and perspectives and apply it to our own knowledge/work accordingly

Remember that the CRAAP Method is just one tool for helping you think through information evaluation. The ultimate determination about whether an article, book, or web source is appropriate to your project is your audience, which might include your teacher, classmates, or a public audience of readers. You should always be asking yourself: what does this source teach me? how can I use it? will my audience be persuaded by the sources I have included?

Examining Bias

Cognitive Bias

Sometimes when we pick and choose information, our own biases and lived experiences lead us to seek certain sources over others. This is called confirmation bias, which occurs when you only seek out evidence that confirms what you already believe or interpret evidence in a way that confirms your existing beliefs.

Let’s apply these ideas to the common practice of searching the internet for information. By recognizing cognitive biases, you can find the most accurate and reliable information:

First, use Google to search results for “women 78 cents on the dollar.”

Then, use Google to search results for “women 80 cents on the dollar.”

Searching for something you already believe to be true can lead you to finding results that support that belief (confirmation bias). For example, if you search “women 78 cents on the dollar,” you get results that say women make $0.78 on the dollar compared to men. If you search “women 80 cents on the dollar,” you get results that say women make $0.80 on the dollar compared to men.

On the other hand, searching for the more neutral term “wage gap” is more likely to provide balanced results. How else can you avoid confirmation bias in your search terms? Consider one more example:

First, search results for “are we eating too much protein.”

Next, search results for “protein nutrition.”

Notice the difference between the search terms “are we eating too much protein” and “protein nutrition.” The first gives results that indicate eating too much protein is bad. Authors that have this viewpoint are more likely to use the words “too much protein” than people who do not. The search “protein nutrition” gives results that are more neutral. Only using terms that frame a topic a certain way will produce biased results. It is similar to asking a leading question (Did you have a great day?) vs. a neutral question (How was your day?). Can you think of a topic where framing bias might be hiding in your search terms? How can you make them more neutral?

Availability Bias

When searching, you may be tempted to click on the first result you see, which can lead you to the anchoring bias and cause you to frame all other search results within the context of the first. To avoid this, think about what types of information you want to find and what makes an authoritative source before you search. If you don’t see the types of sources you were expecting, reformulate your search.

Consider how search engines choose which results to put first. Is it based on accuracy, relevance or popularity? If it is based on popularity, how does that influence the accuracy or relevance of the source?

When reading an informative source, it may not feel natural to question the information being presented. Since what you are reading is the most available information to your mind at the moment, it is likely to dominate your thinking. Try to outline the author’s argument and then question each point of the argument. Actively search for information that opposes the information presented so you can get a balanced view of the topic. How else might the availability heuristic affect how you seek and read information?

Consensus Bias

When reading information that opposes your personal viewpoint, you may be more likely to dismiss the author’s arguments. Since false consensus bias leads us to believe that others think the same way we do, it can be hard to accept that others have different beliefs that are also valid.

To avoid the false consensus bias, approach the information like a scientist with a hypothesis. Acknowledge your hypothesis and be willing to accept that the hypothesis may be wrong. In science, a wrong hypothesis is celebrated as learning something new. Let it be the same with exploring information. Why might you want to avoid the false consensus bias?

Information evaluation is not a simple process with a universal right or wrong answer. Your instructor may require you to use only academic, peer-reviewed sources for a term paper, but such sources may be less appropriate for a different audience. If you are giving a presentation to a local non-profit group about resources for helping refugees in your community, academic sources may be less relevant than language learning blogs or social media posts about food banks and other outreach programs. If you are trying to convince colleagues at a business whether to invest in a new company, financial data, trade magazine articles, and market reports may be more relevant than an article from an academic journal of economics.

Even in college writing courses, you may find you need to make the case for the sources you use, depending on the situation. In general, it may be helpful to start thinking of information evaluation and the application of information as a conversation with your audience. That may mean getting into the habit of talking to your professors and librarians about the information you find and about whether it is of good quality and appropriate for your assignments.

Ultimately your evaluation of information will depend on many factors that you can’t predict. The CRAAP method and the information on examining biases are tools to help you move through your research plan. Once you understand the principles, you can apply them to any rhetorical situation you encounter or any writing assignment you have to complete

Fake News

The term fake news has gained popularity in the last five years. According to Google Trends, Google searches for fake news dramatically increased during the presidential campaign of 2016. Fake news is simply news that is untrue, often shared with the intent to mislead or influence audiences.

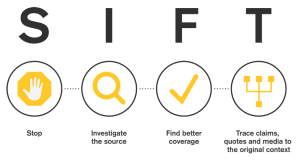

The spread of misleading information (or misinformation) is not a new phenomenon. The first recorded instance of misinformation occurred in Rome from 44 to 31 BC when Marc Anthony’s opponent for the role of emperor, Octavian, started a smear campaign with etched coins that ultimately led to the Battle of Actium (Posetti). Today, misinformation has saturated the information landscape and continues to impact our elections, our society, and our everyday lives. The spread of misinformation is serious, but it can be checked. Tre are four steps you can take to identify fake news using SIFT, which stands for stop, investigate the source, find better coverage, and trace claims, quotations, and media to the original context.

Stop.

When you click a link to a webpage or read a post on social media page, stop and ask yourself whether you know the website or source and what the reputation of the source might be across multiple audiences. If the URL is unfamiliar, take a moment to research the background or readership of the source. If you haven’t heard of the source prior to clicking on it, don’t share it until you have more information.

Investigate the source.

Know what you are reading before you read it. How? Research the source! Professional fact checkers quickly and efficiently do this through lateral research, or independently verifying the source. Rather than reading the “About Us” section of a website and relying on whatever potentially misleading information may be presented there, a professional fact checker opens a new tab in their browser and searches for information about the source from other websites. For example, if you come across an article on the American College of Pediatricians webpage, it may be tempting to trust its claims. However, if you dig deeper by doing a search on the organization, you’ll find that the American College of Pediatricians is actually classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The organization you actually want to trust bears a similar name, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and holds a reputation as a respected and long-established professional organization for pediatricians. Use your research skills to avoid falling into misinformation traps like this one.

Find better coverage.

Just because information exists on a website does not mean it’s reliable. Even news sources have bias and sometimes outright false information. Take a moment to view the Media Bias Chart by Ad Fontes Media to determine the political leanings of some well-known news sources. Ideally, you should find information that is meant to inform you with accurate facts and evidence rather than persuade you through biased accounts or interpretations. Be wary of articles that make an emotional appeal to the audience or use inflammatory language.

Trace claims, quotes and media to the original context.

Context is everything. Much of the information you encounter has been edited and tailored with specific audiences in mind. Are you getting the whole story? It is hard to know without tracing shared information back to its original source. Advances in technology have made misleading videos, including deepfakes, increasingly difficult to spot. Visit this article from The Washington Post to see just how convincing video manipulation can be.

Helpful Resources: SIFT

For more information on the SIFT method, take about 10 minutes and watch the following videos from SIFT method creator, Mike Caulfield:

Online Verification Skills — Video 1: Introductory Video – YouTube

Online Verification Skills — Video 2: Investigate the Source – YouTube

Online Verification Skills — Video 3: Find the Original Source – YouTube

Attributions

“SIFT (The Four Moves),” Mike Caulfield, Hapgood, CC-BY.

“Journalism, Fake News, & Disinformation,” Posetti, J. et. al., UNESCO, CC BY-SA, https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/journalism_fake_news_disinformation_print_friendly_0.pdf.

Adapted from “Palni Information Literacy Modules: Module 5: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources,” LibGuides, CC-BY, https://libguides.palni.edu/instruction_resources/ILModule5.

Adapted from “Thinking about Primary Sources,” CC-BY, https://libguides.palni.edu/instruction_resources/ILModule5.

“Journalism, Fake News, & Disinformation,“ Posetti, J. et. al., UNESCO, CC BY-SA, https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/journalism_fake_news_disinformation_print_friendly_0.pdf.

Adapted from “Research: A Step-by-Step Guide: Primary/Secondary Sources,” LibGuides, CC-BY-SA, https://libguides.centralia.edu/c.php?g=383652&p=2600069.

Boolean terms image from “Information Literacy in Action.” OER Commons. https://sites.google.com/a/onalaskaschools.com/tech/boolean-search-tools

Image courtesy of School District of Onalaska.

“Evaluating Information – Applying the CRAAP Test,” Merriam Library at California State University, CC-BY, https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf.

“Examining Our Biases,” adapted from “Information Literacy in Action: Cognitive Biases,” OER Commons, CC-BY, https://www.oercommons.org/courses/information-literacy-in-action-cognitive-biases.

“Examining our Biases” examples, Michael A. Caulfield, Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, CC-BY, https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/454.