3 Organization & Style

In this chapter, we will practice:

- reorienting to organic and genred essay structures

- composing logical, fluid, and cohesive paragraphs

- recognizing and writing topic, transition, and concluding sentences

- pulling together different types of writing to create organic text structures that take the reader on a journey

- understanding what voice is made of

“Composition,” in writing, is made of three primary sets of decisions: 1) what content will be included in 2) what order and through 3) what phrasing or articulation. In other words, composition is made of organization and voice. In this chapter, we will begin to think about and begin to practice these skills.

Organizing Paragraphs

A paragraph is a unit of text—most likely several sentences in length but not always—that focuses on a particular idea or point. When we divide our writing into these units of text, we do so to break up the flow of information into manageable chunks, which in turn gives structure to how we present our ideas in writing. When you send multiple text messages back-to-back instead of sending one overly long text, you’re writing in paragraphs. When you compose a social media post and hit the spacebar to drop down a line, you’re writing in paragraphs. Whether we realize it or not, most of us write paragraphs every day, but few of us understand how these units of text came to be.

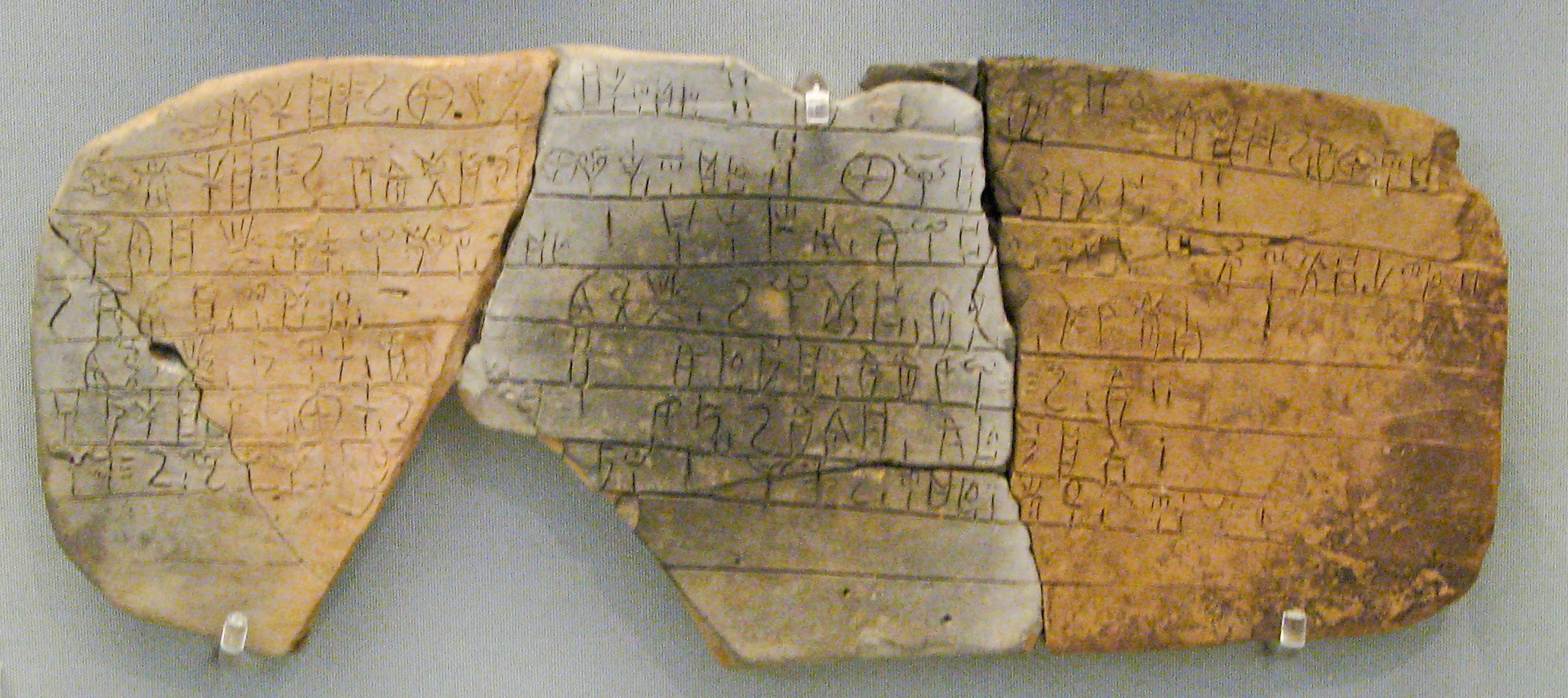

If you enjoy history, you might be interested to know that paragraphs have been around for longer than the invention of paper. Historian of rhetoric Richard Leo Enos posits that the earliest etchings or “scratch marks” around letters on Greek tablets denote early forms of the paragraph (46). In the infamous clay tablet that follows below, you can look closely to see where lines are drawn to break up the flow of ideas. Additionally, scholars now believe that the development of the paragraph derives from the ancient stage direction cue used at intermission, called the parabasis, or the moment at intermission when the chorus would come on stage to sing to the audience between acts (Enos 56). Although there aren’t any choir members hitting high notes between your paragraphs, your paragraphing (the action of breaking your writing up into paragraphs) will function similarly in providing the reader a moment to lay the ideas of the previous paragraph to rest before transitioning to new ideas in the next paragraph.

How do you know when “enough is enough”—when you have enough information in one paragraph and have to start a new one? A very rough guide is that you need more than one or two paragraphs per page of type. Paragraphing conventions online require even shorter paragraphs, with multiple short paragraphs on one screen.

It’s best to deal with paragraphs as part of the revision step in the writing process. Find places where the information shifts in focus, and put paragraph breaks in those places. You can do your best to paragraph as you draft but know you’ll address paragraphing more during the revision process.

Building Body Paragraphs

In essays and articles, body paragraphs are those that come in the middle of the text. In other words, if it’s not the introduction or the conclusion paragraph, then it’s a body paragraph. Body paragraphs typically begin with a key sentence (sometimes called a topic sentence) and are followed by one or more sentences that develop claims, paraphrase or directly quote from sources, and synthesize or provide analytical commentary on the evidence provided. At the end of the body paragraph, a concluding sentence wraps up the main point of the paragraph or segues on to the next paragraph.

Helpful Resources

For more detailed instruction on building body paragraphs, we highly recommend Athena Kashyap and Erika Dyquisto’s Strategies for Developing paragraphs.

Key Sentences

In many essay and article genres, readers expect each paragraph to have a sentence or two that captures its main point. They’re often called “topic sentences,” though many writing instructors prefer to call them “key sentences.” Such sentences are sometimes explicit, openly announcing the topic of the new paragraph. And sometimes they are implicit, signaling their shift subtly. Either way, they signal to the reader the central idea of the paragraph.

Example of an explicit key sentence: “Now that we understand the prevalence of food deserts in major cities and their impact on vulnerable populations, let’s think about how communities can address the problem.”

Example an implicit key sentence: “First, there are small but powerful steps local organizations can take to improve food access without municipal or corporate cooperation” OR “We can also address the problem of food deserts by petitioning local governments to apply for national grants and take steps to attract certain kinds of businesses.”

Now, consider the following examples about epidemiological evidence, meaning evidence related to the study of diseases. Etiological studies refer to the study of the origin of a disease.

Version A: “Now we turn to the epidemiological evidence.”

Version B: “If the evidence emerging from etiological studies supports the hypothesis, the epidemiological evidence is also compelling.”

Both versions convey a topic; it’s pretty easy to predict that the paragraph will be about epidemiological evidence, but only the second version establishes an argumentative point and puts it in context. The paragraph doesn’t just describe the epidemiological evidence; it shows how epidemiology is telling the same story as etiology. Similarly, while Version A doesn’t relate to anything in particular, Version B immediately suggests that the prior paragraph addresses the biological pathway (i.e., etiology) of a disease and that the new paragraph will bolster the emerging hypothesis with a different kind of evidence (epidemiological). The topic or key sentences make it easy for the reader to keep track of how the essay moves from one paragraph and idea to the next.

Topic sentences have a topic and an angle, just like thesis sentences. But the angle of topic sentences usually is smaller in range than that of the thesis sentence. Very often the topic remains the same from thesis to topic sentence, while the angle shifts as the writer brings in various types of ideas and research to support the angle in the thesis.

Developing Ideas, Developing Discussion

Once you have identified the topic of your paragraph, you need to think through your ideas and flesh them out so that you’re reader can understanding what you are thinking, what you are feeling, and/or what position you are taking. Below are ways writers and speakers develop their ideas. Remember, writers choose strategies they believe will best reach their audience, including genred expectations. For example, you are unlikely to find personal testimony in an engineering journal. You are equally unlikely to find statistics in a Taylor Swift song. Both strategies are effective, both ways of speaking are powerful, but they speak differently to different audiences.

- Examples or testimony: clarify your meaning and help your reader connect to your ideas with specifics.

- Data: use facts and statistics to support your points.

- Analysis: break the topic down into its constituent parts and then analyze each part.

- Comparison and contrast: highlight your idea’s similarities to or differences from another concept.

- Cause and effect: discuss possible causes of the topic and any consequences or effects it may have.

- Definition: consider whether the topic needs a definition. Would a definition help make your point?

- Evaluation: judge the topic’s value or power by examining possible significance and implications.

- Classification: classify the topic into a group to expound on your definition and provide examples in the form of like items.

- Narration: tell a story about the topic

Creating Coherence & Cohesion

There are many strategies for making paragraphs that “make sense,” meaning a reader can follow their logic and understand their meaning whether the paragraph is doing exposition, description, or narrative. Organizing paragraphs in the following ways can help create coherence and cohesion.

- Enumeration: follow a numerical pattern of one, two, three . . .

- Chronology: use time to tell a story, or explain how a process unfolds.

- Space: start at the top of whatever you are describing and move to the bottom, or move from left to right, inside to outside, etc.

- General to specific/abstract to concrete: although this pattern can be reversed, usually the general statement comes first, followed by supporting details, explanations, and evidence.

- Order of importance: move from the most important point to the least important, or vice-versa.

Specific word choice can also assist paragraph logic and “flow.” Consider the following:

- Repeat key words to keep the reader focused on your main points. For example, if I am writing about food deserts, I am going to use that term repeatedly as well as associated language like “scarcity,” “access,” “residents,” “healthy,” “affordable,” “hunger,” “vulnerable,” and “at risk” to remind my reader what is at stake.

- Be consistent in number, point of view, and verb tense to keep your readers on track. For example, if you use the plural noun “students” in one sentence, you wouldn’t want to randomly switch to “student” in the next. Likewise, don’t randomly switch between past and present tense.

- Use parallel structure for ideas that are similar. For instance, to describe how writers procrastinate, you might say: “Writers inevitably find ways to put off writing. They answer their email. They pay their bills. They water their gardens. They do everything but write.” Using the same short subject-verb-object sentence structure in the three example sentences reinforces that the delaying tactics listed are similar.

Transitions

Transitions are words or phrases that indicate linkages in ideas. When writing, you need to lead your readers from one idea to the next, showing how those ideas are logically linked. Transition words and phrases help you keep your paragraphs and groups of paragraphs logically connected for a reader. Writers often check their transitions during the revising stage of the writing process. (Note that several of the key sentences in the previous section also include transitions.)

Here are some example transition words to help as you transition both within paragraphs and from one paragraph to the next.

|

Transition Word / Phrase: |

Shows: |

| and, also, again | More of the same type of information is coming; information expands on the same general idea. |

| but, or, however, in contrast | Different information is coming, information that may counteract what was just said. |

| as a result, consequently, therefore | Information that is coming is a logical outgrowth of the ideas just presented. |

| for example, to illustrate | The information coming will present a specific instance, or present a concrete example of an abstract idea. |

| particularly important, note that | The information coming emphasizes the importance of an idea. |

| in conclusion | The writing is ending. |

From sentence-to-sentence, paragraph-to-paragraph, the ideas should flow into each other smoothly and without interruptions or delays. If someone tells you that your paper sounds choppy or jumps around, you probably have a problem with transitions. Compare these two sentences:

- Proofreading is an important step in the writing process. Read your paper aloud to catch errors. Use spell check on your computer.

- Proofreading is an important step in the writing process. One technique is to read your paper aloud, which will help you catch errors you might overlook when reading silently. Another strategy is to use spell check on your computer.

The second example has better transitions between ideas and is easier to read. Transitions can make a huge difference in the readability of your writing. If you have to pick one aspect of your writing to focus on during the revision process, consider focusing on adding effective transitions to help your reader follow your thinking.

Concluding Statements

Ending a paragraph is comparable to politely leaving one conversation before you begin another. Most people try not to “ghost” their friends by exiting in the middle of a conversation. Instead, they use verbal and non-verbal cues to indicate that the conversation is coming to a close. Why? Because people love having a sense of closure at the end of social exchanges.

Writing, like talking at a party, is another type of social exchange. When you write a paragraph, you’re communicating ideas that help to build relationships and understanding between you and your reader. At the end of a paragraph, your reader expects you to give some closure to the discussion with a concluding sentence that ties the paragraph up in a neat and tidy bow. Perhaps your concluding sentence ties up several loose ends by bringing all the ideas together in one statement that unifies or demonstrates the connections among the ideas discussed. Or you might opt instead to comment on how the points are very relevant to your shared interests or could be points of further discussion. Finally, you might segue by moving the conversation in a new direction or toward a new idea.

Here’s an example of a segue sentence that transitions the reader out of the topic of one hypothetical paragraph (maybe focused on disputing the long-term viability of cults from a sociological perspective) and into the topic of the next paragraph (which might be a historian’s evidence-based perspective on cults):

“Although plenty of sociologists have debated the long-term viability of cults, some historians provide contradictory evidence to confirm the staying power of cults over time.”

Do you see how the example concluding sentence points back before pointing forward? This rhetorical move ties up the focus of the last paragraph while also working to keep the reader interested in what comes next.

Organizing Texts

Saying goodbye to the five paragraph essay

As a simplified template, the five-paragraph essay (5PE) taught in high school can make organizing content and ideas feel manageable to students, and can make grading feel easier for teachers than navigating dozens of differently-organized essays. By beginning with an introduction paragraph, three supporting paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph that summarizes the argument, the 5PE is predictable and provides every student with the same roadmap for putting their content together.

And yet in writing, as in life, oversimplified, quick-fix solutions rarely work. The reality is that the 5PE isn’t a realistic structure for communicating effectively with audiences you’ll write for in college classes or other world situations. Sometimes 5PE is a good idea; other times, not so much. Consider these five reasons for reconsidering whether or not to use a 5PE:

- 5PEs revolve around a thesis, but not all academic or professional writing assignments need a thesis statement. Some might require a less argumentative controlling idea, a tagline, or another form of argument that your teacher will discuss with you. In other words, not all compositions are purely thesis driven. Consult with your instructor to clarify what they expect in terms of central message development and how that will structure the piece you write.

- 5PEs flatten any argument. Any issue you write about will be complex, and any argument you make about an issue will necessitate exploring many dynamic viewpoints and facts. Oftentimes, three paragraphs isn’t enough to touch on every angle of an issue. You may need more paragraphs and more points than you can reasonably fit into five paragraphs.

- 5PEs limit creativity. Making meaning is hard to do when you’re limited in terms of how you can package it. Or as Associate Professor of English Quentin Vieregge asks, “What fun is it to write when you have no choices, when the shape of your words and thoughts are controlled by an impersonal model that everyone uses, but only in school” (211)? When you allow yourself to compose beyond the 5PE structure, you open yourself up to a world of creative possibilities.

- 5PEs lack flow. In the next section, we’ll touch on organically structured essays that aid the reader in moving through a text. Ideally, you want the relationships among your paragraphs to give a clear sense of connection, to flow well, and to build reader interest. These organizational aims are difficult to achieve when you’re constantly pointing back to a singular idea rather than letting ideas naturally build off of one another.

- 5PEs fail to transfer. When writing a lab report for a biology course, for example, a 5PE organizational scheme probably won’t suffice for the purpose of that assignment nor will a 5PE help you write a strong memo for a business class. Scientists don’t cram their study findings into five quick paragraphs nor do journalists whittle down every feature to five tidy parts. The point is that 5PEs don’t transfer easily into many real-world writing contexts, so limiting yourself to this organizational approach precludes you from practicing organizational development skills that will benefit you in future writing contexts.

At this point, you might be thinking to yourself, “Is it ever okay to use the five-paragraph essay?” The answer depends on a range of factors related to your rhetorical situation (audience, purpose, context), and, of course, you’ll want to consult with your instructor about their preferences, but rest assured that the 5PE isn’t an inherently flawed way of composing. It’s simply one way of composing that won’t transfer to every rhetorical context you’ll encounter.

Embracing organically structured and genred essays

Unlike the 5PE, an organically structured essay is one that doesn’t follow a predetermined or prescribed organizational pattern, but instead incorporates transitions among paragraphs that feel natural and build connections between paragraphs. At times, the paragraphs and transitions may meander or wind around differing or oppositional viewpoints, but a sense of connection among ideas always exists and the organization is developed to build reader interest.

What does it mean to establish a sense of connection among the ideas you’re writing about? One way to understand connection in writing is to imagine you’re watching a group photo session at a local park. Maybe the group is dressed up and ready to go to prom or maybe it’s a family photo session. In either scenario, the people being photographed can choose to arrange themselves in relation to other people in ways that feel natural or unnatural. We’ve all seen the cringe-worthy prom pose pics where two people are standing uncomfortably close or far apart, or most of us have witnessed the awkward family photos that, despite good intentions, are almost uncomfortable to look at because the physical positioning of some family members in relation to others feels rigid and forced. Good photographers know that the trick to making the subjects of a photo look relaxed and natural is to have the people on camera gather close, reach out to one another—maybe by placing a relaxed hand on another person’s shoulder—and chat amongst themselves to feel at ease. These small ways of socially connecting with other people are reflected in the overall composition of the photograph. In much the same way, an organically structured essay conscientiously builds natural connections among paragraphs so that the overall composition feels cohesive and genuine.

For anyone dreading the loss of the 5PE, the authors of “Organically Structured Essays” offer sage advice: “A good starting place is to recharacterize writing as thinking. Experienced writers don’t figure out what they want to say and then write it. They write in order to figure out what they want to say.” Journaling or freewriting is one way to determine exactly what you want to say and how many points might naturally structure a piece if you weren’t limited by a 5PE.

So, how do we build a sense of connection among our paragraphs? We must think about the paragraphs like we would people in a picture. How will the paragraphs reach out to one another? First, we’ll define what exactly a paragraph is, and then we’ll get into some of the nuts-and-bolts techniques for using paragraphs as units of meaning that forge connections among ideas.

Text Introductions

Many writers share that they have trouble getting started writing an introduction. By the time they’ve reached the midway point of the essay, they might feel like they’re cruising toward a smooth conclusion paragraph; however, the time they spend staring at a blank page up until that midway point can feel paralyzing. To save yourself time, it’s important to clearly understand what most audiences expect to be in an introduction paragraph and to try one of these tried-and-true strategies for opening your piece.

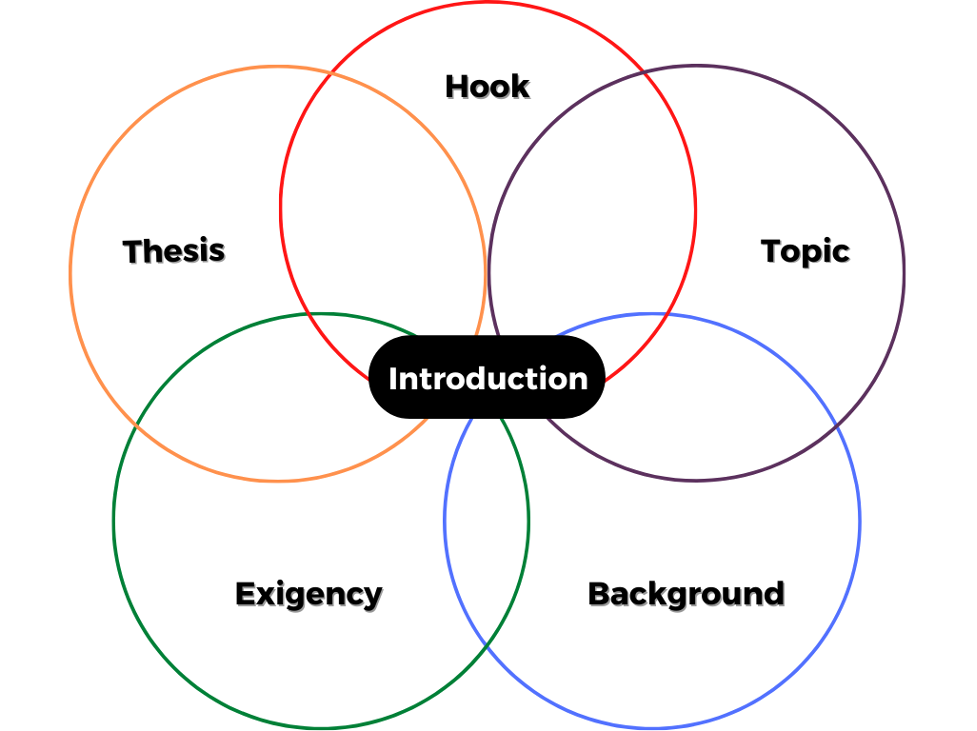

First, know that an introduction paragraph can take on many different forms. In some genres of writing, the introduction will be spread across a few short paragraphs, but in traditional academic writing it tends to be centralized into one primary paragraph at the beginning of the piece. In this first paragraph, the introduction typically begins with an attention-getting hook, a clear statement of the topic to be explored, a central message in the form of a thesis statement or tagline, any additional background information that is needed, and a sense of exigency or urgency that is invoked to make the topic appealing to the reader. Sometimes the elements needed in a solid introduction can overlap. As is the case in all writing scenarios, you should ask yourself “What does the paragraph need in order to fill in any gaps and make sense to the reader?” as opposed to “What elements of an introduction have I not included yet?” With much to consider, let’s start by covering what the elements entail.

A hook is typically the first sentence in your piece and the one that grabs the interest of the reader. Hooks come in many forms and serve various functions. To choose the right hook for your piece, you might ask yourself: “What do I want the reader to be enticed by at the start of this piece? What information would hook me if I were the reader?”

Some hooks are very direct in providing thought-provoking information while others opt for a more creative approach. For instance, it’s common for writers to begin a piece with a startling statistic or fact to entice the reader to keep reading. Occasionally, facts from history, case studies of particular people, or a relevant quotation pave the way for a smooth introduction into the topic at hand. On the flip side, creative hooks might set the scene for the reader through the development of a personal sketch, a fascinating dialogue between two people, a brief narration of a scene, a bold or shocking statement, or a thoughtful question. These are just a few strategies to consider when deciding how to hook your reader.

After you’ve hooked your reader, you will want to provide enough background information on the topic in order to help the reader understand the focus of the piece. For example, you might be writing a paper on a dangerous cult leader, and so the initial background information you provide can offer the reader specific context that is essential to understanding the focus of the piece. In journalism, a funny term for providing such context is the “nut graf” or “nut graph,” which is a sentence or two detailing the most important facts of the story. To write out these contextually rich sentences, consider using the 5 Ws + 1 H heuristic, which involves asking yourself what the who, what, where, when, why, and how of the piece is? In this cult leader context, you might ask yourself:

Who is the cult leader?

What cult did they lead?

Where did the cult form?

When did the cult form?

Why did the cult end?

And how did the cult function in society?

After answering those questions, I might respond with the following nut graf:

David Koresh led the Branch Davidians, a religious cult located outside of Waco, Texas, which ended when authorities from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms raided the cult’s facilities in 1993.

Notice how every question that was originally posed can be answered by the statement above. It’s relatively simple and straightforward, and yet lots of necessary information is packed into one sentence so that the introductory paragraph isn’t overly long.

You can read more about thesis statements in Chapter 4, and you might consider how thesis statements can augment a sense of exigency, or the feeling that you need to become involved in or take immediate action in response to an issue, event, or crisis. A first paragraph introducing a 1990s religious cult might not seem like a timely topic that people need to take action on. However, if you remind readers that history can repeat itself and religious or political zealots must always be kept in check, then you will build a sense of exigency that will motivate your reader to keep reading into the body paragraphs.

It’s worth noting that not all writers compose their introduction paragraphs first. In fact, some writing teachers insist that the best way to get started is to begin writing out your body paragraphs first, and once you know what the bulk of your paper will cover, you can write the introduction paragraph last. One of the biggest benefits of this approach is that you won’t spend too much time toiling over an introductory paragraph that you’ll want to change later because it doesn’t represent how fruitfully your ideas evolved through the process of writing. Although this approach doesn’t work for everyone beginning a new draft, this approach can be helpful later in the writing process, too. That is, if you begin your composing of a piece by writing the introduction paragraph first and your body paragraphs later, consider rereading and revising your introduction to ensure that it accurately reflects what follows in the subsequent paragraphs.

Discussion: Why Titles Matter

The title of a text is the first thing that calls to a reading audience. The title must divulge what your paper (or idea, argument) is about, but it also has to stand out from other, similar works on similar topics. And it is your first opportunity to draw in people to listen to, or read about, your thoughts, opinions and ideas.

The Nature of Writing by Conrad van Dyk has a video about creating an effective title.

Text Conclusions

Unlike the grand entrance the introduction makes, the conclusion paragraph often plays second fiddle, which means that it takes on more of a supporting role. Certainly, your conclusion can have just as big of a starring role in the overall production of your piece as the introduction does, but the rhetorical impact of this paragraph is largely up to you and dependent upon the expectations of your audience. Nevertheless, there are a few key moves that function like stage cues in how well they refocus the reader’s understanding of the overall performance of the piece by this ending point.

- Cue the Finish. Choosing the right introductory phrase to indicate that your piece is coming to a close. Some phrases that will help signal to your readers that the end is near include: “In conclusion…” “Overall…” “In light of…” “Furthermore…” “Finally” or “Lastly.” Many more exist, but you might try experimenting with one of those phrases so that the reader knows you’re wrapping up.

- Restate Your Argument. Harken back to your thesis statement or the controlling idea you led with in the introduction paragraph. You might reword or try to paraphrase what you originally wrote, or you can even try to add onto this initial argument with additional key details or claims that came up in your body paragraphs. The purpose of a sentence or two restating your argument isn’t to bore the reader or yourself with old information but to give a sense of cohesion and completeness to the overall piece.

- Call to Action. Much like the exigency established in the introduction, the conclusion paragraph should stress the importance of the topic or issue explored in the piece. Ideally, the emphasis placed on the seriousness of the issue motivates the reader to take action and provides actionable steps the reader can take in order to effect change. For instance, you might list a few easy steps that readers can take in order to reduce their carbon footprint on a daily basis or you might share information on how to sign a petition for policy reform. The more specific and attainable the action step is, the more likely the reader is to act.

- Focus on the Future. If a call to action doesn’t quite work with the topic you explored in your piece, you might create a final, future-oriented sentence. Some writers might gesture back to a startling statistic delivered earlier in the piece or others might end on a positive note of hope. In the latter scenario, it’s not uncommon for writers to ask their readers parting questions, such as, “Twenty years from now, will the children living at the Texas border know a better life than they do today?” or “Having read this piece, will you go to school tomorrow thinking about how you can be more supportive of your neurodiverse classmates?”

Remember, these strategies for closing can take many forms. You can end with a metaphor, a description, dialogue, a question, a declaration, a word.

Arranging body, introduction, and conclusions paragraphs

The genre you’re writing in will likely be the most important determining factor in deciding when to paragraph or where to place your paragraphs. For example, the organizing principles for an argumentative essay based on research and citation of multiple sources will require you to think about where you’ll place the paragraphs that make the strongest points, whereas an analysis essay may require a spatial or appeals-based organization that guides the reader through various elements within a written, oral, visual, or electronic artifact. In this section, we’ll discuss different theories guiding writers’ arrangement of paragraphs.

- Primacy vs. Recency. To elaborate on the organization of argumentative, research-based essays, some writers tend to think in terms of primacy versus recency. When a writer steps back to look at the many paragraphs they wrote, they might rearrange paragraphs to place their strongest points in strategic locations. When organizing with primacy in mind, a writer might place paragraphs featuring their strongest claims and evidence early on in the piece to persuade readers from the start. With primacy, the writer strategically chooses if they want their reader to encounter persuasive information immediately so that they read the rest of the essay in agreement with the author. When a writer arranges the paragraphs to build toward or end with their strongest paragraphs toward the end, then the writer is organizing with recency in mind. Arranging paragraphs to end with the most persuasive information can help to win over a skeptical audience needing more information to be built into the body of a text before deciding if they’ll agree with the author.

- Chronological. Of course, some texts lend well to chronological organizations. If you’re writing an essay that will contain many dates or pertinent historical events, then a chronological organization enables you to arrange paragraphs in accordance with a historical timeline. For analyses, a chronological order sometimes works to support the writer and reader in moving carefully, one-by-one through the placement of features of a text to be analyzed. For narrative essays, a chronological organization can feel like an easy go-to method for developing your organization. However, take special caution to avoid giving a simplified plot summary for narrative essays, and consider structuring a narrative essay out-of-order or in a non-linear fashion much like thriller movies do to keep the audience interested and piecing together what happens next.

- Spatial. A spatial organization can be incredibly helpful for arranging paragraphs in analysis papers, particularly those that are geared more toward visual rhetorical analysis. Spatial relates to the word space, and when conducting a spatial analysis, you might think about how the eye moves across the space of a text. For example, when we naturally analyze, our eyes tend to look for focal points, centering objects, or the directions lines create. When we start by analyzing what we see first, next, and so on, we take the reader with us as we visually break down numerous elements of a text. Imagine you’re looking at a painting of a fruit bowl in a museum, and there’s a gigantic pineapple sitting in the center of all the other fruits. As opposed to a chronological organization, which moves in a left-to-right linear order, a spatial organization might start in the center of a picture because the largest element is anchored there. After analyzing the color, texture, and stylistic features of the pineapple, you would move not to the element right next to it but to the next element in the painting that catches your eye. Maybe you notice a corner window shining light onto the bowl. That would be the next element to write a paragraph of analysis on in your spatial organization.

- Parts- based. In Chapter 4 or 5, more information on the persuasive appeals of ethos, logos, and pathos is provided, and these appeals might be useful to you in organizing an analysis focused on rhetorical appeals. You might consider choosing one of these appeals to develop an argument about how that particular appeal can be used to understand the rhetorical purpose of a text. On the other hand, some students favor speaking to each of the appeals by giving a paragraph or more to each one. If you go this route, be sure to actively contemplate if you want to touch on each of the three appeals in order to form a 5PE or if your instructor would like to see you write beyond a 5PE.

Cultivating Style

We use the term “style” to refer to the unique and distinctive choices that authors make, imbuing their work with a sense of personality and individuality. “Style” refers to the way a writer constructs their sentences (syntax), chooses their words (diction), and uses their voice. “Style” is like an aesthetic; it carries the writer’s personality or brand. Some writers have a writing style that’s very ornate—long, complex, and beautiful sentences, packed with metaphors and imagery. Others have a more straightforward style—sparse prose, simple sentences, etc.

“Style” is often linked to particular genres. “Academic writing,” for example, is a genre that tends to require a writing style that is formal, detailed, authoritative, and neutral. Newspaper articles tend to be written in a style that is direct, succinct, and accessible so that people can get the information they need quickly.

Elements of style include:

- Syntax aka. sentence structure: the ways linguistic elements are arranged to create meaning. Sentence length is a matter of syntax, as are complexity and the arrangement of clauses. Choosing different kinds of syntax allows writers to create their voice, persona, and particular meaning.

- Diction: word choice and how writers assemble meaning by putting together certain words based on their sounds, literal meaning, and cultural connotations.

- Voice: the way the author uses diction and syntax to project or embody a particular personality or identity. Voice encompasses easy-to-define elements like passive/active voice and POV and also embodies less tangible qualities like “ethical” or “empathetic” or “powerful” or “scared.”

- Imagery: technique for the writer to appeal to the reader’s five senses as a means to convey the essence of an event. It means to recreate a thing, bring it to life, in the reader’s imagination.

- Figurative language: type of communication that does not rely on a word’s direct definition, but uses different words to convey meaning.For example, when you say you have “butterflies in your stomach,” you are speaking figuratively to embody fluttering, panicked nerves. There are many types of figurative language. We will discuss a few in this section.

Syntax

There are four types of sentences:

- Declarative: Makes a statement. The dog is sleeping in the corner.

- Interrogative: Asks a question. Where is the dog?

- Imperative: Gives a command. Come here, dog.

- Exclamative: Expresses surprise. Look at that sweet dog!

And there are a few basic sentence patterns:

- Subject/ verb: The dog ran.

- Subject/ linking verb/ subject compliment: The dog is a German Shepard.

- Subject /action verb/ direct object: The dog bit the mailman.

- Subject/ action verb/ indirect object/ direct object: The dog brought me a stick.

- Subject/ action verb/ direct object/ object compliment: The dog made the mailman angry.

Writing qualities like rhythm, variety, clarity, and voice come from creating, playing with, and pushing together different types of sentences and sentence patterns. Here are some suggestions for varying and playing with sentence structures or creating different tones.

- Combine multiple simple sentences to create a smoother feel and show relationships between ideas. OR break up sentences into smaller ones if you want to jolt your reader. Use the FANBOYS acronym for remembering coordinating conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So

-

- We write. We edit. vs. We write and we edit.

- He went to the store. He bought apples. vs. He went to the store to buy apples

-

- Vary the location of dependent clauses and phrases. Use subordinating conjunctions for creating dependent clauses: that, which, who, whom, whose, when, where, why, after, although, as, as if, because, since, so that, how, whenever, and so on.

-

- When he went to the store, he bought apples.

- He bought apples when he went to the store.

- He bought apples when he went to the store, but she bought bananas.

-

- Utilize transition words and phrases to guide your reader through your thought process and create flow. You can also use conjunctive adverbs like: thus, therefore, thereby, consequently, however, additionally, furthermore, nonetheless, moreover, likewise, and so on.

-

- I went to the grocery store and considered buying kiwis, but then I remembered my roommate doesn’t like kiwis and bought apples instead.

- I went to the grocery store and considered purchasing kiwis. However, upon reaching the produce section, I remembered my roommate does not care for kiwis, and therefore purchased apples instead.

-

- Avoid repeating “to-be” verbs to make your voice more direct and/or more authoritative.

-

- Writing is what I enjoy > I enjoy writing.

- Smoking is bad for your health > Smoking causes damage to your health > Smoking destroys parts of your body

-

- Use parallel structure. Sentence elements that are alike in function should also be alike in construction, or parallel. Below are some examples of parallel elements. Notice the patterns in language:

-

- thinking, running, singing, seeing (Gerunds: Notice the “-ing” ending verbs)

- to see, to understand, to speak, to stir (Infinitives: The word “to” and then a verb)

- on the street, on the table, on the radio, on the mark (Prepositions: The words “on the” and a noun)

- who you are, what you are doing, why you are here (Clauses: The five Ws and how)

-

Vocabulary

Parts of a Sentence

- Subject: Usually contains a noun or pronoun and is the topic of the sentence and does an action.

- Predicate: This is the action that the subject does.

- Direct vs. Indirect object: Ex. Sally bakes Joe a cake. The cake receives the action of being baked, which makes it the direct object; however, the cake is baked for Joe, so he is the indirect object.

- Independent clause: Contains a subject and predicate and can stand alone as a sentence. ( Ex. I run., He eats., They laugh.)

- Dependent (subordinate) clause: Group of words that can’t stand alone as a complete sentence, but is dependent on, or subordinate to, the independent clause. (Ex. Although I run,).

- Prepositional phrase: a group of words that begins with a preposition (and ends with a noun, pronoun, or noun phrase (this noun, pronoun, or noun phrase is the object of the preposition). Prepositional phrases modify or describe nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs and are used to clarify relationships in sentences. Some of the most common prepositions that begin prepositional phrases are to, of, about, at, before, after, by, behind, during, for, from, in, over, under, and with.

Parts of Speech

- Nouns: Persons, places, things, or ideas; function in a sentence as subject, direct object, indirect object, object complement, predicate nominative, object of a preposition, or appositive

- Verbs: Actions or states of being; function in a sentence as either an action verb or a linking verb.

- Pronouns: Words that take the place of nouns: function in a sentence as subject, direct object, indirect object, object compliment, predicate nominative, object of a preposition, or appositive

- Adjectives: Describe nouns

- Adverbs: Describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs

- Prepositions: Words that signal prepositional phrases and show relationships between words and phrases; function in a sentence as either an adjective or an adverb

- Conjunctions: Words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses; coordinating or subordinate.

Diction

Another way to improve on the quality of writing is to consider modifying your diction, or word choice, in a piece of writing. Diction refers to an author’s choice of words, phrases, or sentences. Diction can be formal or informal depending on the needs of the document and expectations of the audience. Diction, therefore, concerns itself with emotional and cultural values of words and their ability to affect meaning.

Consider the word “laugh.” We all know what it means to laugh, but instead of merely writing laugh in a sentence, a clever writer may consider using alternative words and take advantage of the effects they create. Ponder the words giggle, cackle, and chuckle, all of which also mean to laugh, but note how they create distinctly different meanings within the same sentence.

Examples:

- The old lady’s giggle echoed throughout the quiet house. (silly, fun-filled, childlike, perhaps a bit naughty)

- The old lady’s cackle echoed throughout the quiet house. (scary, witch-like, intending evil)

- The old lady’s chuckle echoed throughout the quiet house. (explosive, sudden, loud sound)

These sentences show how a simple word variation can not only change the meaning of a sentence, but it can establish an overall mood to the work itself.

Diction choices can include the use of:

- Slang. Recently coined words used informally. Ex: yeet, fleek,

- Colloquial expressions. Regional sayings like “y’all” and “you guys” that are informal.

- Jargon. Words or expressions that pertain to a particular profession or activity.

- Dialect. A language style with its own vocabulary and grammar patterns, usually using words that reveal a person’s social class, economic level, or ethnicity.

- Concrete diction: Words that describe physical qualities or conditions.

- Abstract diction: Words that describe ideas, emotions, conditions, or concepts that cannot be touched.

- Denotation: The exact, dictionary definition of a word, free of secondary definitions or emotion. Ex: That car is jacked up. Someone slid a jack under the car and hoisted it up.)

- Connotation: The social meaning of a word, containing suggestions, emotional overtones, or other associations. Ex: The car is jacked up. (Translation = That car is messed up!)

- Euphemism: A nice way of saying something too ugly to utter. Ex: dead = passed away

- Synecdoche: A part of something used to refer to the whole of it. Ex: Nice wheels! (Wheels are a part of a car, but really, you’re referring to the whole car.)

- Metonymy: When a word/phrase refers to something related but doesn’t have to deal with any part of anything. Ex: Jana has a nice ride! (Here, a “ride” really means a car.)

Figurative Language

Figurative language is a type of communication that does not rely on a word’s direct definition, but uses different words to convey meaning.For example, when you say you have “butterflies in your stomach,” you are speaking figuratively to embody fluttering, panicked nerves. Common in comparisons and exaggerations, figurative language is usually used to add creative flourish to written or spoken language or explain a complicated idea. Whatever the tactic the author uses, it is meant to make the reader connect to the characters/events through lively description in a deeper way than if the author just said something plainly.

- Ex: “A single second, as big as a zeppelin, floated by.” -“Greasy Lake” by TC Boyle

Explanation: The author simply could have said that time seemed to have stood still at that precise moment, but he didn’t. Instead, he used a simile to tell the same idea but to create a more intense effect. The result, of course, is much more powerful.

Below are common types of figurative language.

- Similes. Comparing two different things using “like” or “as”

- Metaphors. Comparing two different things not using “like” or “as”

- Hyperbole. A severe exaggeration. “It’s a thousand degrees outside!”

- Apostrophe. Directly addressing a person, thing, or abstraction, such as “O Western Wind,” or “Ah, Sorrow…” and is sometimes seen in religious texts or odes.

- Onomatopoeia. A word whose sounds duplicate the sounds they describe. Ex: hiss, buzz, bang, murmur, meow, growl.

- Oxymoron. A phrase with contradictory parts. Ex: jumbo shrimp, Biggie Smalls, a cold sweat, pretty ugly.

- Paradox. Concepts or ideas that are contradictory to one another, yet, when placed together hold significant value on several levels. Ex: Here’s some advice: Never take my advice!

- Kenning. A newly created compound sentence or phrase to refer to a person, object, place, action or idea. Ex: Battle-sweat = blood, Sky-candle = sun, Whale-road = ocean

- Metonymy. The name of one thing for that of another of which it is associated. A crown (royal object) rests on his crown (part of a person’s head).

- Synecdoche. A part of something to refer to the whole. Ex: Get your butt in here! (Really, all of you.)

- Litotes. A discreet way of saying something unpleasant without directly using negativity. Ex: Not the brightest bulb (not very smart)

- Understatement: An ironic understatement meant to downplay a situation and make it seem less than what it really is. Ex: “He’s not the sharpest tool in the shed.”

Imagery

In terms of writing, imagery is more than creating a pretty picture for the reader. Imagery pertains to a technique for the writer to appeal to the reader’s five senses as a means to convey the essence of an event. It means to recreate a thing, bring it to life, in the reader’s imagination. The five senses include sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste. The writer does not need to employ all five senses, only those senses that most effectively convey, transport the reader into that event. Imagery engages the reader with specific sensory details. Imagery creates atmosphere/mood, causing the reader to feel a certain emotion. For example, a scary scene includes details that cause a reader to be frightened:

Ex. “The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the habiliments of the grave. The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have had difficulty in detecting the cheat. And yet all this might have been endured, if not approved, by the mad revellers around. But the mummer had gone so far as to assume the type of the Red Death. His vesture was dabbled in blood — and his broad brow, with all the features of the face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.” – “Masque of the Red Death,” Edgar Allan Poe

Imagery can be used throughout an entire essay, such as a description essay that focuses on a particular event. Writers should first decide what atmosphere/mood they want to create for their readers and then focus solely on the sensory details that convey that particular atmosphere/mood. For example, if a writer wanted to share the experience of a favorite holiday meal, then s/he would focus on the smells and tastes of all the food and the memories that those smells and tastes conjure. The hectic grocery shopping for all the ingredients would be omitted since that would not express the nostalgia of the meal.

Imagery can also be used per individual paragraph as a means to illustrate a point. For example, in an essay arguing for a ban on smoking, one paragraph could detail the damage to lungs caused by smoking.

Practice: Imagery

A brainstorming technique for imagery involves drawing a picture by focusing on one sense at a time. So, find a blank sheet of paper and various colored pencils. You can do this activity in one of two ways; by (1) attuning to what is around you in the space you are in to practice sensing, or by (2) imagining a setting you love or miss or wish to tell someone about.

First is sight. Slow down to mentally picture every object, shape, color, person, and so on in the scene. Draw, as best you can, representations of each of those visual details. (Only you will see this drawing; no need to stress over perfection.)

Next, take a different sense, such as sounds, and record those sounds on paper with various colors, symbols, or onomatopoeia. (Again, do the best you can to represent what you heard. Your goal is to remind yourself of the sounds, not create a work of art.)

Next, take a different sense and record that particular sense on paper with various colors and symbols.

The objective is to slow down and focus on each sense individually rather than trying to remember the scene all at once. By slowing down and envisioning each sense on paper, you can determine which senses most accurately create the atmosphere/mood for the essay and then apply only those senses in the essay

Using Mentor Papers to Understand How Different Authors Compose

Making decisions about how to organize your paragraphs, what content to include in your body versus conclusion, and what words to use in what order with what sentence structure can be overwhelming. In these moments, it can be helpful to look at the work of others to understand the decisions they have made as inspiration and direction for your own decision-making. Composition studies scholar Ann Berthoff once compared the great balancing act that is writing to learning how to ski:

Let me speak from my experience as a profoundly unathletic person . . . [My ski instructor’s instruction was to do thus and do so with my knees, to hold my arms this way and not that way, etc.] All that happened was that I continually pitched forward and fell in the snow. But suddenly across the meadows, I saw a figure going like the wind—a young man in shorts and a tee shirt, obviously a serious skier! And as I watched I suddenly saw the whole shape of the act of skiing; I saw the Gestalt; I got the rhythm, the allatonceness of the action. I did what I saw and I shot across the snow! What I needed was not a model which could show me how the various gestures and stances and operations fitted together, but an image of how cross-country skiing looks, and kinesthetically, how it feels. The image of the skier gave me the whole process; it represented the allatonceness of cross-country skiing. (89)

Berthoff is suggesting that sometimes we need to stop and study how others are writing before launching confidently into our own process of organizing a piece. This does not mean to copy someone else’s work or to use their work as a template. It means looking closely at a piece that you think is successful to understand how it works in order to inform how your piece will work. Look for opportunities to study models, to talk to other students in your class about how they’re organizing their papers, or even to ask your instructor questions about their writing process sometimes. Instructors are often happy to pull back the curtain on organizational techniques that work for them, but you may not know until you ask.

Practice: Autobiographical Essay Mentor Paper

To better understand how other writers organically structure their paragraphs, try creating a table that will help you see how the parts (paragraphs as units of text) establish a whole (a system formed through units).

To start, locate a model piece of writing or a mentor text you want to emulate. If you are working in a specific genre, you might want to choose a well-known text within it. If you are thinking about a class assignment, you can look at former student examples. Then, create a three-column table that features one row for every paragraph in the mentor text plus one extra row for creating column labels at the top of the table.

For your autobiographical essay assignment, we recommend reading one of these pieces professional autobiographical narrative essays and then using this activity to carefully unpack it to think about organization and style.

#Julian4Spiderman by Julian Randall

“The Eternal Springs of Balmorhea State Park” by Katie Guttierez”

“Sometimes You Have to Get Lost” by Hal Niedzviecki

In the first column of the first row, write “Paragraph Number.” You can then number each row, and correspondingly, you can number each paragraph in your mentor text to match with the numbered rows.

In the second column, write the question: “What does the paragraph say?” In each numbered row for this column, you’ll provide a short sentence or a few relevant details that give you a sense of the paragraph’s most important points.

In the third column, write the question: “What does the paragraph do?” In each numbered row for this column, you’ll provide your reflection on the purpose of the paragraph. You might describe the overall rhetorical effect of this paragraph in comparison to other paragraphs or describe how the points in the paragraph support the thesis statement. Whatever you choose, try not to repeat what the paragraph is saying but focus on interpreting why the paragraph is making the points that it is.

An excerpt from a completed synthesis table for another paper can be seen below:

|

Paragraph Number |

What does the paragraph say? |

What does the paragraph do? |

|

1 |

Gives a few statistics about cult activity and argues it can be dangerous and at-risk populations should be monitored | This paragraph introduces the concept of cults through startling statistics before giving a thesis statement. |

|

2 |

Describes the history and details of a specific cult | This paragraph provides more needed background information to provide the reader with context. |

|

3 |

Offers specific statistics about young people drawn into cults and groups of people who are more susceptible to cult recruitment strategies | This paragraph ties back to the thesis statement and provides more facts to make the argument more persuasive. |

Once you’ve written out what each paragraph is saying and doing, you might look back at the synthesis table more holistically to understand how the writer carefully built out their argument.

After looking at other writers’ work, you can create a synthesis table for essays you are writing or have written, after which you might ask yourself:

-

- Do I need to rearrange any of my paragraphs to improve the flow of information in my piece?

- Do I need to add any paragraphs or information to paragraphs that will help each paragraph connect back to my thesis or central message?

- Is there anything more I need to say (or further points or facts to be added) or anything more that I need to do (adding or rearranging paragraphs) to increase the overall flow of this piece

Attributions

“Key Sentences,” Lumen Learning, CC BY: Attribution, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/englishcomp1/chapter/topic-sentences/.

“Organically Structured Essays,” Lumen Learning English Composition I. CC BY-NC-SA, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/englishcomp1/chapter/organically-structured-essays/.

“Paragraphing and Transitioning,” Excelsior OWL, CC BY: Attribution, http://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/paragraphing/paragraphing-and-transitioning/.