9

By Keelan Boyle, Katherine Corbin, and Daniel Shea

Introduction to Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is an island territory of the US in the Caribbean with a vast history and culture. With a population of 3.2 million, Puerto Rico has gone through dramatic changes in the hundreds of years that Westerners have been aware of it (CIA, 2018). Over the years, the prevalent economic driver has shifted from agriculture and a slave-based labor system to today’s growing industrial sector (Fain et al., 2018). With this shift, as well as the increasing effects of climate change and hurricanes, the climate has become an increasing worry for the citizens of the magnificent island. Solutions have since been found to try to combat these problems.

The History and Culture of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico has been inhabited for over 4000 years (since 2000 BCE) by people who first settled in the vast mangrove ecosystems (Rob, 2016). Around two thousand years later the Saladoid people came to Puerto Rico from modern day Venezuela and brought more advanced agriculture and pottery techniques to the island and replaced the existing Ortoiroid culture (Rob, 2016). As this civilization continued to thrive it expanded across the Caribbean. This new Saladoid society had a focus on politics and art. After Christopher Columbus made his journey to the Americas, the Spanish started to take control of the island (1508 CE) (Pierce, 2010). In 1523 the first sugar cane processing plant was established, starting one of the main industries of the island along with coffee, which was introduced to Puerto Rico during the 18th century. After the Spanish-American War (1898) the USA incorporated Puerto Rico as a territory (Pierce, 2010). On August 12, 1898, President William McKinley and French Ambassador Jules Cambon signed an armistice in Washington DC, stripping Spain of its control over Puerto Rico, as well as Cuba and the Philippines, and giving control of these countries to the United States (Rivera, 2020). Puerto Rico was officially ceded to the United States on September 29th, 1898 (Rivera, 2020). The reason the United States decided to take control of Puerto Rico was to implement a strong sugar market here (Little, 2017). Ironically, this industrialization has led to decreasing agricultural suitability.

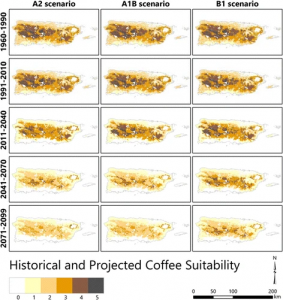

Another major industry in Puerto Rico that had a significant presence on the island was coffee production. Climate change has created disadvantages to agricultural sales around the world, one of these being coffee production (Fain et al., 2018). Coffee production was at its peak in the late 19th century, but when the United States took the country over in 1898 as a result of the Spanish-American war, it was easily able to industrialize Puerto Rico. This made agriculture scarcer (Fain et al., 2018) and led to current harvesting reaching record lows. The reduction of rainfall around Puerto Rico due to climate change has also negatively impacted its remaining agricultural farms. Projections show that Puerto Rico could hold only 24 square kilometers of suitable land for agriculture by 2071, which takes up less than 0.3% of the island (Fain et al., 2018). As one can see in figure 1 under even the best conditions, coffee suitability is projected to exponentially decrease in the next 20 years despite the availability of land.

Puerto Rico was not always known for its industrial cities and unsuitable agriculture. In 1815, the country developed a strong agricultural economy, where the main investments included cattle, sugar cane, tobacco, and coffee (Rivera, 2020). However, by 1867, which was the onset of the industrial revolution, agriculture was limited by lack of roads, low quality tools, and natural disasters, such as hurricanes and droughts. This brought about a sharp increase of poverty-stricken citizens since agriculture was the main source of Puerto Rico’s income (Rivera, 2020).

Despite poor agriculture and decreasing coffee suitability, Puerto Rican residents are resilient when it comes to climate change. The Greater Antilles region has been subject to historic periods of high precipitation and low sea levels. Puerto Rican residents have responded to change in precipitation in various ways; one example being the people of Angostura, who reside in northern Puerto Rico, who relied heavily on their location. Because of this, they implemented technology to adapt to this change (Rivera-Collazo et al., 2015). Residents of the Maruca group in southern Puerto Rico, however, were not as reliant on their location, so they would evacuate until more ideal conditions came about (Rivera-Collazo et al., 2015). Both locations are directly on the coast. The locations of these groups and the resources they had show how Puerto Rico has adapted due to climate change. All in all, Puerto Rico is a land with rich history and various cultures spanning back 1,000 years before the arrival of the Spanish (Britannica, 1999). These various cultures have led to Puerto Ricans responding to seasonal climate change in numerous ways, depending on their values and priorities.

Major Industries and Economic Health

The major industries in Puerto Rico have been greatly impacted by climate change. Since Puerto Rico has poor agriculture, the industrial sector plays a more significant role in the economy. Tourism, one of Puerto Rico’s major industries, also significantly impacts the economy. Very low job opportunities in Puerto Rico has caused a rise in outmigration to the mainland of the United States, with the unemployment rate of Puerto Rico hitting 16% in 2011 (CIA, 2018). This number eventually declined to 11.5% in December 2017 (CIA, 2018). The minimum wage laws that are present in the US apply to Puerto Rico which has halted job expansion and the income per capita to about two-thirds of the mainland of the US (CIA 2018). The economy in Puerto Rico has also been greatly impacted by the effects of climate change. Persistent and strong hurricanes have greatly damaged electricity in Puerto Rico impacting manufacturing and the economy. Even though Puerto Rico is a US territory, it rarely receives aid from the mainland after these natural disasters. This has also negatively hurt Puerto Rico and its economy.

Land Use, Resources, and Ecology

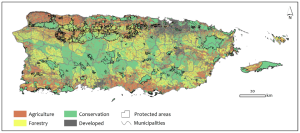

Tourists come to Puerto Rico from all over for a tropical paradise with sandy beaches, a tropical climate, and the multitudes of forests that cover the Cordillera Central, the main mountain range on the island with an elevation of 3000 feet [see the middle map of figure 2] (Britannica, 1998). Coming down from the mountains are a multitude of different rivers that supply animals and people with water. The La Plata River and the Río Grande de Loíza are two of the island’s longest and most important rivers (Britannica, 1998). Both provide unique services to the island; the La Plata River provides hydroelectricity and the Río Grande de Loíza provides water for a vast number of agricultural needs (Britannica, 1998). Both rivers also support forests that cover approximately 63% of the 8,959 square kilometers of Puerto Rico (CIA, 2018). As explained earlier, the amount of land used for agriculture has been significantly reduced over the last few decades. This has allowed the forest to take back much of the island with the help of humans from the 1950s to now (Brandeis et al., 2009). With humans introducing new species and changing the environment, the variety of species of trees is at an all-time high and no local trees have gone extinct. Within the forests and other environments there are over 9,000 different species of animals in Puerto Rico. This includes many endangered species whose homes are being destroyed due to habitat loss. One of the more notable endangered species is the Puerto Rican Parrot (see Figure 4), whose habitat for these parrots is in forests with suitable notches for nesting and fruit for food. There are fewer than 200 of these birds left on the island and only 30 left in the wild (Endangered Species Coalition).

With the introduction of more and more humans to the island, the forests have gone though many different changes. This includes the near-total annihilation of old growth forests and the carving up of land for agriculture; at one point up to 68% of the island was cleared for agriculture, even though agricultural land only occupies 13.4% of the island currently. The other major use of land is for industry (CIA, 2018). As the modernization of Puerto Rico and its economy continues, the amount of land used for industry will also increase from the current 14.8% (CIA, 2018). This will cut into the forests and tax the natural resources on or near the island. A driver for this is the vast amounts of oil and natural gas that are off the island’s coast. With the shift towards renewable energy sources, however, these resources may not be used for a long time. If Puerto Rico were to pursue renewable energy, the main sources would most likely be solar, wind and hydroelectric.

Effects of Climate Change and Environmental Issues

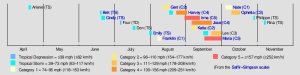

Puerto Rico has experienced its fair share of environmental and social problems due to climate change. There are significant social issues present in Puerto Rico including class divide and an uncertain political status (Comas-Diaz et al., 1998). On top of this, Puerto Rico has experienced the impacts of increasing natural disasters due to climate change as seen in Figure 5. In September of 2017, Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico causing electrical power outages that impact 90% of the territory. There was significant damage to infrastructure and housing with the contamination of drinking water (see Figure 6; CIA, 2018). Often when Puerto Rico experiences natural disasters like Hurricane Maria, the US will not help repair the damage. Despite and because these significant environmental issues that are present in Puerto Rico, efforts have been made in the territory to look at the use of solar energy for small rural water systems. The high cost of electricity in Puerto Rico has greatly impacted the treatment and distribution of clean drinking water. In 2019, the EPA conducted a research project in which they looked at the efficacy and the possible use of solar-powered water delivery systems in Puerto Rico (Patterson et al., 2019). The rural water system that was present was damaged by Hurricane Maria, but solar panels were not damaged (Patterson et al., 2019). Solar energy could be beneficial in Puerto Rico and could help with the damage caused by Hurricane Maria and other natural disasters. Other measures have also been taken in Puerto Rico to protect the environment and to act against climate change. In 2007, the “Puerto Rico Declaration on Climate Change” was signed in order to evaluate the impacts of climate change and assess possible adaptation and alternatives to global changes in Puerto Rico (PRCCC, 2013). Groups like the “Puerto Rico Climate Change Council” have made great change regarding environment issues and slowing down climate change in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico has experienced the impacts of climate change and has also made actions to lessen its affects.

Conclusion

As a small, poor island territory Puerto Rico and its many people and communities are particularly vulnerable to various natural disasters and changes in the environment. Industrialization of the economy has caused environmental issues have started to hurt the vast amount of biodiversity and different population centers. But with this, there are organizations that are looking to combat the effects of climate change on Puerto Rico.

References

Bhardwaj, A, Misra, V., Mishra, A., Wootten, A., Boyles, R., Bowden, J. H., & Terando, A. J. (2018). Downscaling future climate change projections over Puerto Rico using a non-hydrostatic atmospheric model. Climatic Change, 147, 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2130-x

Brandeis, T. J., Helmer, E. H., Marcano-Vega, H., & Lugo, A. E. (2009, August 11). Climate shapes the novel plant communities that form after deforestation in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Forest Ecology and Management, 258(7), 1704-1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.07.030

CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). (2018, February 1). The World Factbook: Puerto Rico. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rq.html.

Comas-Diaz, L., Lykes, M. B., & Alarcón, R. D. (1998). Ethnic conflict and the psychology of liberation in Guatemala, Peru, and Puerto Rico. American Psychologist, 53(7), 778-792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.53.7.778

Britannica, Matthews, T. G., Wagenheim, K., & Wagenheim, O. J. (Eds), (1999). History of Puerto Rico. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Puerto-Rico/History

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. (1998, July 20). Cordillera Central. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Cordillera-Central-mountains-Puerto-Rico.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2019, December 26). La Plata River. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/La-Plata-River.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2010, November 1). Loíza River. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Loiza-River.

Fain, F., Quiñones, M., Álvarez-Berríos, N. L., Paréz-Ramos, I. K., & Gould, W. A. (2018). Climate change and coffee: Assessing vulnerability by modeling future climate suitability in the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico. Climatic Change, 146, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1949-5

Flores, L. P. (2010). The History of Puerto Rico. Greenwod Press.

Little, B. (2017, September 22). Puerto Rico’s complicated history with the United States. History. https://www.history.com/news/puerto-ricos-complicated-history-with-the-united-states

Miller, G., & Lugo, A.E. (2008). Guide to the ecological systems of Puerto Rico. General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35. Rio Piedras, PR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry. 437 p. https://data.fs.usda.gov/research/pubs/iitf/iitf_gtr_35.pdf

Mongabay.com. (n.d.). Puerto Rico Forest Information and Data. Tropical Rainforests: Deforestation rates tables and charts. https://rainforests.mongabay.com/deforestation/2000/Puerto_Rico.htm

Patterson, C., G. Ramirez, C. Maldonado, H. Minnigh, R. Sinha, & C. Lopez-Maisonave. Benefits of solar energy for small rural water systems in Puerto Rico. AWWA ACE, Denver, CO, June 09 – 12, 2019. https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_file_download.cfm?p_download_id=538523&Lab=NRMRL

Puerto Rico Climate Change Council (PRCCC). 2013. Puerto Rico’s State of the Climate 2010-2013: Assessing Puerto Rico’s Social-Ecological Vulnerabilities in a Changing Climate. Puerto Rico Coastal Zone Management Program, Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, NOAA Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management. San Juan, PR. http://pr-ccc.org/download/PR%20State%20of%20the%20Climate-FINAL_ENE2015.pdf

Rivera-Collazo, I., Winter, A., & Scholz, D. (2015). Human adaptation strategies to abrupt climate change in Puerto Rico ca. 3.5 ka. The Holocene, 25(4), 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683614565951

Rivera, Magaly. (2020). Puerto Rico’s History. Welcome to Puerto Rico! Retrieved November 28, 2020, from https://welcome.topuertorico.org/history.shtml

Rob, A. (2016, September 2). Saladoid: Indigenous Caribbeans. Black History Month 2020. https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/pre-colonial-history/4235/.

Worldometer. (2020). Puerto Rico Population (LIVE). Worldometer. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/puerto-rico-population/.

Winter, M. (2020, June 9). Iguaca – the endangered Puerto Rican parrot. NFWF. https://www.nfwf.org/media-center/featured-stories/iguaca-endangered-puerto-rican-parrot.

Figures

Dutton, N. (2017). Hurricane Damage Assessment [Photograph]. Air Force Magazine, US Air Force. https://www.flickr.com/photos/133046603@N02/23538371048/in/photostream/

Fain, F. (2018). Climate change and coffee: assessing vulnerability by modeling future climate suitability in the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico. Climatic Change, 146(1), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1949-5

Flores, L. P. (2010). The History of Puerto Rico. Greenwod Press.

Gould, W.A., Wadsworth, F.H., Quiñones M., Fain S.J., & Álvarez-Berríos N.L. (2017). Land use, conservation, forestry, and agriculture in Puerto Rico. Forests, 8(7):242. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8070242

Timeline of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season [Timeline]. (2017). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_2017_Atlantic_hurricane_season

Torres, P. (2006). Puerto Rican Parrot / Cotorra Puertorriqueña [Photograph]. USFWS. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usfwssoutheast/5840541824