13

By Katherine Corbin, Nora Smith, and Gabriel Ward

Chapter Summary

Oil drilling in the ANWR would cause environmental damage, affecting the way of life of Native Alaskans by creating pollution and affecting migratory species, as well as upsetting major offsets of pollution. All this would occur with only a minor economic impact, as the amount of oil even in the area is unknown but estimated to be enough to power the economy for only 6 months. To prevent this, we aim to increase public awareness and partner with an advocacy group in order to create government change. The organizations we reached out to all prioritized uplifting the indigenous voice.

Introduction

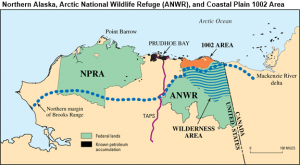

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is one of the last remaining untouched wildlife refuges, located in the northeastern region of Alaska and encompassing an area of 19 million acres. Known for its pristine environment, Indigenous people, and wildlife, this place carries a deep significance to the Gwich’in people who rely on the migratory patterns of the Porcupine caribou herd. Despite the hundreds of years spent living off the land, their home has come under attack in the past 50 years due to oil corporations, who believe there are somewhere between 600 million – 7 billion barrels of oil sitting beneath their sacred grounds. In addition to destroying the centuries-long way of life of the Gwich’in people, potential oil spills can wreak havoc on surrounding wildlife, migratory patterns of caribou herds will change, and local pollution will impact the surrounding ecosystem. Despite all the problems outlined here, many people still support drilling in the Arctic because media outlets backed by the oil industry fuel narratives that encourage drilling. Due to the lack of readily available information, our paper focuses on raising awareness about the negative effects of drilling in the Arctic, and what can be done to prevent it.

Background

The American public is asking for change. In a spring 2020 survey, 79% of US adults said that looking into renewable energy resources is a higher priority than drilling to address the nation’s energy concerns (Gramlich, 2020). It has become clear that the American public is not getting what they want, as corporations continue to lobby in favor of the fossil fuel industry. This entire movement started with the Reagan administration in 1986, as he was the first president to express interest in Arctic drilling (Standlea, 2006). However, when proposed legislation was brought to President Clinton about opening the ANWR on December 5, 1995 he decided to veto it saying that drilling would, “threat[en] a unique, pristine ecosystem in hopes of generating $1.3 billion in Federal revenues—a revenue estimate based on wishful thinking and outdated analysis. I want to protect this biologically rich wilderness permanently.” The White House completely reversed this standpoint during Trump’s presidency, who on March 28, 2017 decided to start leasing land in the ANWR to oil companies. Before this plan could come to fruition, President Biden placed a temporary ban on drilling in the Arctic during his first few days in office. This goes to show how uncertain the future of the ANWR remains, as Indigenous people are currently still seeking protection for their sacred lands. While the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 gave Indigenous peoples title a large land base, this act excluded regions that were known to hold the potential for oil development and, in exchange for the land given to them, all previous claims that would have granted Indigenous people far more land were terminated. In 2005, the Inuit of Alaska, Nunavut and Northwest Territories petitioned the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, arguing that the USA, as a main contributor to anthropogenic climate change, was violating their rights to the use of land for subsistence, health, life, and security (Zentner, 2019). The petition asks specifically for the commission to declare that the US, as the world’s largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions, is in violation of the 1948 American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man. The petition seeks to amend this violation by establishing limits on greenhouse gas emissions and cooperate with the community of nations, including the United States and Canada, to prevent anthropogenic climate change (Crowley & Fenge, 2005).

Protections for Indigenous people are not the only point of contention, from the 1970s-1990s the US underwent a change in how it views environmental policy. In the 1970s the US focused primarily on technical learning, which emphasizes legal solutions such as the Clean Air Act of 1970 (Fiorino, 2002). This preserves traditional standards of hierarchy and removes responsibility from other government branches. This focus started to change in the 1980s when attitudes during the Reagan administration shifted to conceptual learning, which means that the government would intervene less and look at environmental policies in more of a conceptual manner. This allowed for the separation of environmental goals from other political goals, creating debates and de-prioritization for the problems considered less important by those in charge. After the Reagan presidency, attitudes progressed from controlling pollution to preventing pollution. The 1990s also signaled an era in which a shared responsibility to protect the environment was developed that emphasizes connection and contact between “participants,” or those affected by what happens to the system and those that cause changes (Fiorino, 2002).

Looking at drilling in the ANWR from an economic perspective does bring about some fleeting benefits. These include a temporary decrease in the price of oil, less reliance on imports which makes oil less expensive, and temporary job opportunities. A particular area under contention is the 1002 area. This is a biologically important area, estimated to contain 4.24 billion (with a 95% certainty of existence) to 11.8 billion barrels of oil (with a 5% certainty of existence; Kotchen & Burger, 2007). However, these are rough estimates. This means that there is a chance the return on investment of drilling there could be very little when considering oil and expenses used for extraction. And even in a best-case scenario, the oil extracted would not provide the United States with energy for long (Kotchen & Burger, 2007). The rate of oil consumption in United States during 2019 was 20 million barrels per day, which comes out to 7.3 billion barrels per year (US Energy Information Administration, 2021). At this consumption rate, the barrels of oil gained from the lower estimate of oil supply would only provide enough for 212 days of power.

Even with the minor economic benefits, there are major environmental impacts with lasting effects. Opening the ANWR for drilling will increase emission outputs by between 0.7 and 5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. The high end is about 12% of Alaska’s annual emissions (Aton, 2019). This will contribute to further warming the Earth’s climate. In addition to this, migratory animals will be the most affected, as both the drilling and the infrastructure could disrupt their patterns of movement. The Porcupine caribou are the most prominent example, as there are people who rely on their migration being unchanged, but there are many species of migratory birds, including snow geese and bald eagles, that will be affected as well (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 2014). In addition to this, less is known about the impacts on other species but it can be determined that massive amounts of habitat loss will occur. Human disturbances will cause changes in migratory routes for species like caribou that reside in the area. These disturbances will also prevent species from reaching parts of their land and prevent them from accessing the available vegetation (Plante et al., 2018). Many animals, birds in particular, are significantly impacted by oil spills that are likely to occur if the ANWR opens for drilling. ANWR drilling will also promote air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby perpetuating our already self-destructive dependency on fossil fuels. Lastly, drilling ruins the natural scenic beauty of the area. Due to the impacts that drilling would have on the Arctic, actions must be taken to prevent drilling in the Arctic and to inform people of the situation.

Methodology

Our goal is to learn how the US has approached the topic of Arctic drilling through different policies, as well as spending some time looking at drilling through the lens of Native Alaskans. We are also aiming to partner with an advocacy organization to advocate for policy change in favor of the environment. In order to identify different advocacy groups, the group contacted different organizations to learn more about the issues and the missions of the organizations. The group looked into contacting the Audubon Society Alaska, NRDC (National Resources Defense Council), Native Movement, and Richard B. Slats from ARCUS (Arctic Research Consortium of the United States). The group had planned to interview representatives of these organizations and additional research was done to see what work these groups have accomplished and what they have planned.

In addition to contacting organizations, the group also conducted individual research on the effects of drilling in the ANWR. The method used for this research involved utilizing databases such as the WPI George C. Gordon Library, and each team member had specific kinds of effects of drilling in the ANWR to investigate. These effects included economic benefits and drawbacks, environmental impacts, impacts on Indigenous lands and people, and political perspectives on drilling.

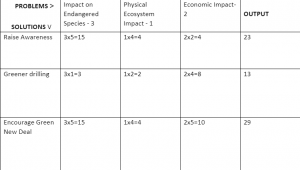

The group used a decision matrix in order to decide what the best possible solution to solve our problem was (Figure 2). This decision matrix helped us look at different problems that would be impacted by drilling and helped us look at how our different possible solutions would impact these problems. Our first solution was to raise awareness of Arctic climate shifts in order to inspire change. We thought that partnering with an advocacy group against Arctic drilling would help shift the views of the public and work towards making bigger changes. Our second possible solution was to investigate options for greener drilling. While this option may not be ideal, it is important to look at other possibilities if drilling in the Arctic cannot be prevented by law. Our third option was to encourage the Green New Deal. This option would help encourage policies that could protect the Arctic from drilling, as well as shift overall climate justice. In the decision matrix the problems were scaled from 1 to 3, with 1 being the lowest impact and 3 being the highest impact. The solutions were then compared to each problem in order to look at how that solution would impact the problem. This was done with number values as well with 5 having the most impact and 1 having the least impact.

Findings and Results

Through our research, we found that drilling in the ANWR has many far-reaching effects that impact the economy, wildlife, and Indigenous communities. From this, we have determined that drilling in the ANWR is not worth the estimated 600 million to 7 billion barrels of oil contained within the ANWR. This gives us a mean estimate of 3.5 billion barrels that can be extracted from the ANWR, which is predicted to power the US economy for roughly 6 months (Standlea, 2006). The effect that this temporary increase in oil production will have is modest, attributing to about a 1% decrease in oil prices.

The tradeoff for drilling in the ANWR far outweighs the short-lived benefits. Indigenous people, particularly the Gwich’in people, have relied on the Porcupine Caribou Herd for sacred hunting practices for hundreds of years. Drilling would disrupt the migration patterns of this herd as well as other wildlife species, putting an end to a critical piece of Gwich’in culture. The impact on wildlife includes more than changes in migration patterns; if the ANWR were opened for drilling, 69 of 157 bird species found in the area could be at particular risk, and the Bering seal population which is already predicted to be extinct by 2095 would see an even more rapid decrease in population size. It is predicted that drilling in the Arctic will increase emissions between 0.7 and 5 million metric tons of CO2 (Aton, 2019). This increase in local emissions will cause sea ice to melt even faster, contributing to the decline in the Bering seal population. This loss of this wildlife will cause a chain reaction of population decline in wildlife, as species such as sharks rely on the seal population for hunting. One of the most concerning side effects of drilling for oil are potential oil spills, which have a significant effect on birds as crude oil and tar that gets stuck in their feathers inhibits their ability to fly, effectively killing them. With these concerns in mind as well as the fact that we as a nation are beginning to move away from fossil fuels, drilling in the ANWR is hardly practical and will only provide a short-lived supply of oil.

Conclusion and Broader Impacts

The primary implication of our findings is how far-reaching the environmental negatives of oil drilling here would be in comparison to how small and short-term the economic positives would be. The local environmental impacts cannot be underestimated either: thousands of Native Alaskans depend on migratory animals like the Porcupine caribou and whales in order to keep food on the table and cultural traditions alive. But if that wasn’t enough, the environmental impacts go deeper still. Upsetting the land in this area disrupts a major carbon sink, releasing previously trapped CO2 into the atmosphere and removing an area where new emissions could have been absorbed (Miller, 2020). Snow and ice need to be removed for infrastructure to be built and trucks to drive, weakening the strength of the ice-albedo feedback loop, which would raise the temperature of the planet even further. Meanwhile, the cause of these long-term environmental effects is a short-term boost to the United States economy. To weigh 6 months of oil against decimation of an important piece of natural climate mitigation and find the oil more valuable is something we hope to turn people away from.

We hope this research shines some light on a highly contested issue that not many people know the specifics of. If we can help people understand the numbers behind the financial gains that are to be had as well as show the environmental losses, we feel that more people would be in favor of stronger government protection for this land. In a theoretical model showing the relationship between social media and an individual’s personal involvement with a movement, likelihood of protesting is directly correlated to how often an individual sees others active in the movement (Little, 2016). The more people are outspoken about protecting this land, the more likely it is that more people will join them. This kind of solution can also be applied to any environmental issue. While it is not as direct as implementing a technology or inventing something new, getting more people invested in saving the planet is never a bad thing, and change starts with individuals.

Recommendations

Our research has led us to three different solutions, each with different pros, cons, and steps to implementation. Solution one is to raise public awareness of the issues that would arise from drilling, putting pressure on corporations and the government to not drill and prevent drilling respectively. Solution two is implementing the Green New Deal or, more generally, introduce more government regulation on drilling to make it safer and less destructive. Finally, if drilling is not fully preventable, solution three is to require companies to implement greener drilling technology in order to lessen the impact of any drilling that occurs in the Arctic.

When reviewing our solutions, we looked at the impacts these solutions would have. The group looked at how these solutions would impact endangered species, the physical ecosystem, and the economy. Oil drilling would have an impact on the calving grounds of caribou and the roosting sites of migratory birds, damaging populations and creating food scarcity for Indigenous tribes. Additionally, it is estimated that opening the ANWR to drilling would cause Alaska’s total emissions to rise by 12% (Harsem et al., 2011). Finally, this is all supported by the fact that there is an unknown amount of oil contained in the ANWR, meaning that a known amount of devastation would occur for an unknown amount of oil.

These solutions are the best possible solutions because they encompass both the best possible solution (drilling is no longer allowed in the area) and the most realistic solution (drilling continues with greener technology). As with any environmental problem, there are no “right answers” here. What would be best for local Indigenous tribes and animals would be to ban drilling there completely, but the Alaskan economy is heavily reliant on oil. Stricter government regulation would keep drilling safer and potentially completely discourage it, but there is very little chance of that happening while oil companies continue to spend millions lobbying politicians. Greener drilling technology seems like a happy medium: corporations still get their oil money, but not without having to consider the environment and the local peoples first.

Native Alaskan populations benefit from a ban on drilling as they will get to keep their land and sacred hunting practices. Wildlife in the ANWR will also benefit from a ban on drilling because oil spills, habitat loss, and increased local warming from emissions in the area will lead to a decline in wildlife populations, alter migration patterns, and already endangered species may go extinct. The only drawback to not drilling in the ANWR is that the potential oil in the area can’t be used to boost the US economy, although the effect drilling would have would be short lived.

Implementation

The solution we chose to try to implement is to raise awareness. In order to do this, we will reach out to an advocacy group that aligns with our goals of prioritizing Indigenous Alaskans and focusing on the environment. This will be done after we research multiple different advocacy groups, their goals, and their prior work. Once we have found a group, we will get in contact with them, as well as seek out individuals within the organization that can provide advice and recommendations on how to best further the group’s accomplishments. The group will continue researching and contacting new groups until we receive a response from an organization that we would like to partner with. A successful collaboration would allow us to become more educated in the proper way to go about our next step: advocating for change.

In order to advocate for change, we plan to conduct further research on the organizations of our choice to learn more about changes they have made to local and global communities and their successes on a local and federal government level. We also plan to conduct an interview with a representative of the organization to find out more details about their plans. This will help us formulate our own action plan to spread awareness as well as educate us on potential challenges we may face. The reason we feel partnering with an organization is so important for this step is because of our position in the world. We are three white students, raised in the continental United States. We can do research and read first-hand accounts, but we will not be able to adequately advocate for what is truly needed by the people in Alaska unless we seek out what they have to say. Every voice matters, but a misinformed voice may do more harm than good.

We will then ask what we can do to help raise awareness and assist with their activities once we have partnered with the organization. With the resources and guidance provided by the organization, we hope to start educating others in the same way the organization educated us: by providing us with a better understanding of the issues and a better knowledge of what we can do to solve it. If COVID permits it, we also hope to be involved in potential marches and protests supported by our organization.

We will see success with this solution if we partner with an advocacy group and assist them in achieving their goals. Through this we hope to convince others to join or support the advocacy group we choose to work with. The ideal goal would be to see policy changes as a result of our actions, which would include a range of things like a ban on drilling, to increased regulations that would make drilling a greener process. Even if we do not achieve this ultimate success, our success includes increased awareness through education, which we achieved simply by giving our presentation at the end of the term. While the three of us do not have much sway in governmental change, we hope that our efforts combined with an advocacy group contribute to changes in attitudes towards drilling in the ANWR. For every person we can make more aware, the less likely they will be to support drilling in the ANWR, and this could lead to real government change.

See Appendix 1 for the infographic of this project used during Project Presentation Day.

Bibliography

Aton, A. (2019, September 16). Drilling could cause extinctions in Alaskan refuge, government plan says. E&E News. Retrieved February 16, 2021, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/drilling-could-cause-extinctions-in-alaskan-refuge-government-plan-says/#:~:text=The%20agency%20estimates%20that%20drilling,12%25%20of%20Alaska’s%20annual%20emissions.&text=Temperatures%20around%20ANWR%20have%20risen%206.5%20degrees%20Fahrenheit%20since%201949.

Crowley, P., & Fenge, T. (2005, December 7). Inuit petition Inter-American Commission on human rights to oppose climate change caused by The United States of America. Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/press-releases/inuit-petition-inter-american-commission-on-human-rights-to-oppose-climate-change-caused-by-the-united-states-of-america/Fiorino, D. J. (2002). Environmental policy as learning: A new view of an old landscape. Public Administration Review, 61(3), 322-334. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00033

Gramlich, J. (2020, August 27). U.S. views on oil and gas production as Alaska refuge drilling advances. FactTank: News in the Numbers by Pew Research Center. Retrieved February 04, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/17/fast-facts-about-u-s-views-on-oil-and-gas-production-as-white-house-moves-to-open-alaska-refuge-to-drilling/

Harsem, Ø, Eide, A. & Heem, K. (2011). Factors influencing future oil and gas prospects in the Arctic. Energy Policy, 39(12), 8037-8045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.09.058

Henderson, J., & Loe, J. (2014). The prospects and challenges for Arctic oil development. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. OIES PAPER: WPM 54. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/WPM-56.pdf

Kotchen, M. J., & Burger, N. E. (2007). Should we drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge? An economic perspective. Energy Policy, 35(9), 4720-4729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.04.007

Little, A. T. (2016). Communication technology and protest. The Journal of

Politics, 78(1), 152-166. https://doi.org/10.1086/683187

Miller, A. (2020, November 21). Oil versus climate change: The economics of drilling in the Arctic. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/21/oil-versus-climate-change-the-economics-of-drilling-in-the-arctic.html

Pelley, J. (2001). Will drilling for oil disrupt the Arctic Wildlife Refuge? Environmental Science & Technology, 35(11), 240A-247A. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0123756

Plante, S., Dussault, C., Richard, J. H., & Côté, S. D. (2018). Human disturbance effects and cumulative habitat loss in endangered migratory caribou. Biological Conservation, 224, 129-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.05.022

Standlea, D. M. (2006). Oil, Globalization, and the War for the Arctic Refuge. State University of New York Press.

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (2014, September 12). Bird list [Fact sheet]. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/arctic/birdlist.html.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2021, January 12). Short term energy outlook – U.S. liquid fuels. U.S. Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/report/us_oil.php.

Zentner, E., Kecinski, M., Letourneau, A., & Davidson, D. (2019). Ignoring Indigenous peoples— Climate change, oil development, and Indigenous rights clash in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Climatic Change, 155, 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02489-4

Glossary

National Petroleum Reserve Alaska (NPRA) – Area of land in Alaska that is owned by the federal government of the United States and is managed by the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management.

A national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska

Ice is more reflective than other surfaces so as ice cover decreases globally, the Earth’s surface becomes less reflective. This causes the surface to warm as more solar radiation is absorbed by the surface