2 Burners and Stingers

A burner or stinger is characterized by brief, unilateral arm pain, paresthesias or weakness after an injury or a specific inciting event. A burner or stinger is caused by a transient brachial plexus injury (so-called neuropraxia) due to traction, compression, or direct trauma to the brachial plexus. It is often associated with collision sports injuries, such as football, that causes bending of the neck and/or displacement of the arm. Treatment is usually not necessary, and players can return to play when and if there is complete resolution of symptoms.

Structure and Function

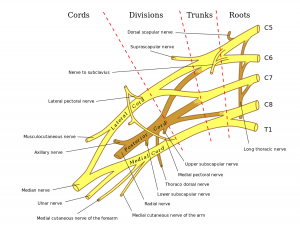

The brachial plexus comprises of nerve roots from C5-T1 (Figure 1). There are five regions to the brachial plexus from proximal to distal: Roots, Trunks, Divisions, Cords, Branches.

Roots – The nerve roots are composed of the ventral and dorsal components, each carrying motor and sensory information, respectively. The two combine to form the cervical nerve roots and exit the spine. The 5 cervical roots combine to form 3 trunks.

Trunks – The superior (C5, C6), middle (C7), and inferior (C8, T1) trunks emerge between the anatomical triangle formed by the anterior scalene muscle, middle scalene muscle, and the first rib. After traversing a short distance, each trunk divides into anterior and posterior divisions.

Divisions – There are six divisions (3 anterior, 3 posterior) that combine into 3 cords, which now have different coverage from the C5-T1 roots compared to the 3 trunks.

Cords – The posterior cord (C5-C8) is formed from the 3 posterior divisions. Prior to the final branches, the posterior cord gives off the upper subscapular nerve (C5, C6; innervates subscapularis), the lower subscapular nerve (C5, C6; innervates subscapularis and teres major), and the thoracodorsal nerve (C6-C8; innervates latissimus dorsi).

The lateral cord (C5-C7) is formed from the anterior divisions of the superior and middle trunks. Prior to its final branching, it gives off the lateral pectoral nerve (C5-C7; innervates pectoralis major).

The medial cord (C8, T1) is formed from the anterior division of the inferior trunk. Prior to its final branching, it gives off the medial pectoral nerve (C8, T1; innervates pectoralis minor and major), the medial brachial cutaneous nerve (T1), and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (C8, T1). Each cord gives off two terminal branches.

Branches – There are five terminal branches (two branches form the median nerve).

- The axillary nerve (C5, C6) derives from the posterior cord and travels to the glenohumeral joint. It mainly innervates the deltoid as well as sensation to the lateral shoulder.

- The radial nerve (C5-T1) derives from the posterior cord and runs medially along the arm with the long head of the triceps until it crosses laterally across the humerus via the spiral groove. The nerve supplies the elbow and forearm extensors and supinators. The nerve also provides sensation to the distal-lateral arm, the posterior forearm, and the posterior aspect of the radial side of the hand (thumb to middle finger).

- The median nerve (C5-C7) derives from the medial and the lateral cord. The cords join anterior to the axillary artery and then travels with the artery along the arm. The nerve innervates most wrist flexors and pronators as well as the two lumbricals on the radial side of the hand. The nerve provides sensation to the anterior aspect of the radial side of the hand.

- The musculocutaneous nerve (C5-C7) derives from the medial cord and pierces through the coracobrachialis muscle to become the most superficial branch. The nerve innervates the biceps, coracobrachialis, and brachialis. The nerve provides sensation to the lateral forearm.

- The ulnar nerve (C8, T1) derives from the medial cord and runs along the medial aspect of the arm, through the cubital tunnel at the elbow and through Guyon’s canal at the wrist. The nerve innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris, the adductor pollicis, and the intrinsic hand muscles (except the two radial lumbricals innervated by the median nerve). The nerve provides sensation to the whole ulnar aspect of the hand.

Most cases of stingers affect the C5/C6 nerve roots or the upper trunk of the plexus.

The most common cause of injury is due to traction on the brachial plexus rather than direct trauma. This can occur in ipsilateral shoulder depression and neck deviation towards the contralateral side, often seen in tackling, which causes stretching of the brachial plexus on the ipsilateral side.

Patient Presentation

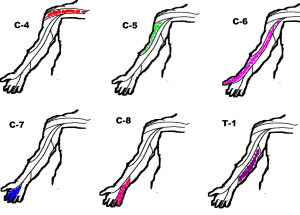

Most athletes present after particularly high-impact collisions, with immediate onset of unilateral, radiating, and severe burning pain down the arm. This may be accompanied by paresthesia in the related sensory dermatome (the area of skin sensation supplied by a given spinal nerve) and motor weakness. Players may be supporting the affected arm using the other arm to relieve tension. Neck pain is usually not present.

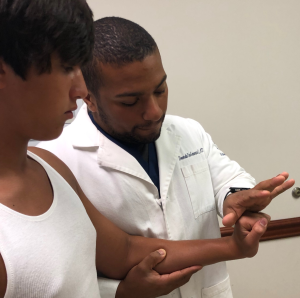

On physical exam, transient sensory disturbances (numbness, tingling, burning, or radiating pain) in the affected arm are common (Figure 2). There may be transient, unilateral weakness in the affected arm with normal biceps reflexes (Figure 3 – Figure 7). (Transient hyporeflexia may be present in a minority of patients).

The key finding is that these symptoms, if present, should be transient. The vast majority of cases resolve within a few minutes to days.

All cases of stingers can be classified into 3 grades. Grade 1 stingers are due to neuropraxia (intact axon but demyelinated). There may be temporary loss of sensation and/or motor function up to days. Grade 2 stingers are due to axonotmesis (axon damage). This produces more significant motor and/or sensory deficits which may last up to several weeks. Last, Grade 3 stingers are due to neurotmesis (severed nerves). This may produce enduring symptoms that may never fully resolve.

Objective Evidence

In most cases of first-time stingers, imaging is not necessary. Initial imaging, if obtained, usually consists of anterior-posterior, lateral, and oblique views of the cervical spine and shoulder area. No abnormal findings are found in most cases of simple stingers. If there are concerns for further pathology due to Red Flag findings mentioned below, and if initial imaging is normal, cervical MRI should be obtained to evaluate the spinal cord, nerve roots, vertebral discs, ligamentous injury, or vertebral fractures.

There are no specific laboratory findings associated with stingers or other cervical spine diseases.

Epidemiology

Stingers are most commonly seen in football players, but can also be seen in hockey, lacrosse, and rugby players. This is because the mechanism of injury is usually forced rapid lateral neck flexion, which can occur during tackling and can cause traction or compression injuries to the brachial plexus. It is estimated that over 50% of football players have reported at least one stinger during their career. The true prevalence of this condition is not known, mainly due to its transient nature and the tendency of players to not report or underreport their symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for stingers is relatively narrow but should be considered in any cases when red flags (as discussed below) are present.

- Cervical radiculopathy: Consider if symptoms persist beyond 24 hours. MRI can help assess for radiculopathy. Presentation may be similar to burners and stingers, other than the timeframe of symptoms.

- Shoulder dislocation or acromioclavicular joint injury: Injury to the bony structures of the shoulder should be considered, especially after traumatic sports injuries affecting one arm. X-rays, CT, or MRI can help assess for injuries to the bones or surrounding soft tissue.

- Thoracic outlet syndrome: This syndrome is thought to be caused by compression of the brachial plexus or subclavian vessels as they pass through narrow passageways leading from the base of the neck and torso out to the arm (the “thoracic outlet”). This compression can cause neck and arm pain and paresthesias in the fingers and hand. At times, the affected hand is pale and cool. Thoracic outlet syndrome seems to be provoked by rotation of the head and neck.

- Cervical spine stenosis or fracture: In severe cases of collision, the actual spinal canal may be damaged. If this is the case, players may present with bilateral symptoms or have symptoms in their lower extremities, which never occurs with stingers. The cervical spine should be immobilized until further evaluation by CT or MRI.

Red Flags

If any of the following signs are present in a patient presenting for stingers, further workup should be considered to rule out the above differential diagnoses.

- Bilateral symptoms: Stingers affect only one arm at a time. Bilateral symptoms should raise concern for spinal canal stenosis or cervical fractures.

- Lower extremity symptoms: Stingers affect only the brachial plexus. Lower extremity symptoms should raise concern for spinal cord injuries.

- Muscle atrophy: Stingers, due to their transient nature, rarely causes atrophy. If significant atrophy is present, consider recurrent stingers or other pathologies.

- Symptoms lasting more than 24 hours: While stingers can last longer than 24 hours, the majority of cases last under 24 hours. Further imaging should be pursued if symptoms last for over 24 hours to rule out more dangerous pathologies, covered above.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

The most important step in treating suspected stingers is to remove the player from play for initial evaluation. A quick but thorough exam of all four extremities as well as the neck should be conducted to assess for findings and red flags discussed in this chapter. A player may return to play upon complete resolution of symptoms and once he/she demonstrates normal strength and range of motion of the affected arm. Recurring or persistent symptoms should be evaluated as discussed earlier. If symptoms last for more than a few minutes, cervical x-rays should be strongly considered to evaluate for fractures or dislocations.

For persistent symptoms, after appropriate work up showing no other pathology, rest and gentle stretching of the affected arm is advised. Physical therapy may be recommended if symptoms persist beyond a few days. Specific stretching and posturing maneuvers can be recommended by the therapist. NSAIDs may be used to alleviate pain during the first few days.

Surgery is almost never considered for stingers. In rare cases of Grade 3 stingers, due to complete transection of axons, surgery may be attempted to repair the damaged axons, but outcomes are poor.

Considering that stingers rarely lead to permanent disability, the general prognosis of first-time stingers is excellent. An estimated 85% players are able to return to play within the same game or practice. A history of a prior stinger can increase the incidence of recurrent stingers, but there is no clear evidence of recurrent stingers causing permanent nerve injury.

Risk Factors and Prevention

The most significant risk factor for the development of stingers is playing contact sports that involve tackling. The majority of such players encounter at least one episode of stingers during their career. The presence of cervical canal stenosis has been associated with increased risk of stingers in athletes.

Prevention efforts should focus on proper tackling techniques and protective equipment. A more upright tackling position may protect the neck from excessive extension, while increased padding and/or cervical collar may help absorb some of the impact.

Miscellany

The five sections of the brachial plexus, in order from proximal to distal (roots, trunks, divisions, cords, branches), can be memorized by the following mnemonic (Randy Travis Drinks Cold Beer).

The three terminal branches that form the famous M of the brachial plexus, in order from lateral to medial (musculocutaneous, median, ulnar), can be recalled by thinking MuMU (µ, M in Greek).

Key Terms

Cervical spine, brachial plexus, stingers/burners, sensory dermatome

Skills

Draw a “wiring diagram” of the brachial plexus from memory. (It’s always on the test!) Perform a comprehensive physical exam to evaluate neurologic signs and symptoms. Counsel players on safe sports techniques and appropriate equipment to reduce future recurrences.