5 Disorders of the Acromioclavicular Joint

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is the junction between the clavicle and acromion process of the scapula. Subluxations and dislocations of this joint are colloquially called “shoulder separations” (perhaps to preserve the terms shoulder subluxation and shoulder dislocation for the glenohumeral joint). Patients with AC joint separations commonly present with pain after an athletic injury or fall onto the shoulder. Injuries to the joint rarely require surgical correction. They are generally managed non-operatively with excellent outcomes. The AC joint is also subject to early degenerative change. Arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint is a common cause of focal pain, especially in athletes.

Structure and Function

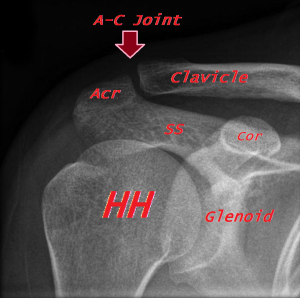

The acromioclavicular joint is the articulation between the distal clavicle and the acromion process of the scapula (Figure 1).

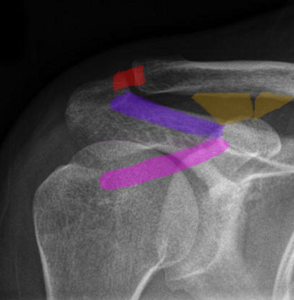

The joint is stabilized by the acromioclavicular ligament (also known as the “AC” ligament), which provides horizontal stability. The coracoclavicular ligament (also known as the “CC” ligament) provides vertical stability. The coracoclavicular ligament is actually a ligament complex composed of two parts: the more medial conoid ligament and the more lateral trapezoid ligament. The trapezoid is the more lateral, inserting about 3 cm from the end of the lateral (so-called “distal”) clavicle, and the conoid inserts about 1.5 cm medial to that (Figure 2).

The coracoacromial ligament (also known as the “C-A” ligament), which runs from the coracoid process to the acromion, forms an arch that helps constrain the humeral head.

Some additional dynamic stability is provided by the deltoid and trapezius muscles.

The AC joint is neither fixed nor rigid, allowing for small amounts of gliding movement, typically accommodating about 5 mm of translation in every plane.

The joint itself is a synovial joint that is encased by a capsule that projects an intra-articular disc into the joint space.

If a person were to fall directly on the point of the shoulder, the acromion is forced inferiorly while the clavicle maintains its position. If the forces are greater than the tolerance of the ligaments, the joint will separate.

Patient Presentation

Acute AC joint separations typically present after a fall on an adducted shoulder, often playing a contact sport such as football or hockey.

A patient will present with pain over the AC joint that limits shoulder range of motion, both passively and actively. Possible swelling or ecchymosis can occur over the AC joint with displacement of the arm and shoulder downward and forward causing the appearance of a prominent clavicle.

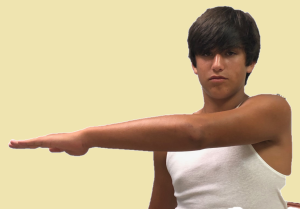

AC joint osteoarthritis presents with chronic discomfort localized to the joint. Patients may report difficulty using the arm or sleeping on the affected shoulder. At times there is a sense of clicking or snapping during use. On physical examination, there is tenderness to palpation of the AC joint (Figure 3), a prominence of the distal clavicle (due to osteophytes) can be seen, and there is focal AC pain with cross body adduction of the arm (Figure 4).

Often, AC joint osteoarthritis is seen in patient’s who lift weights, particularly those that axially load the shoulder (i.e., bench press). In some of these patients, the pain can be rather acute, the joint may be swollen, and radiographs may demonstrate osteolysis of the end of the clavicle (regional osteopenia). This condition has been termed osteolysis of the distal clavicle, or more commonly, “weight lifter’s shoulder.”

Objective Evidence

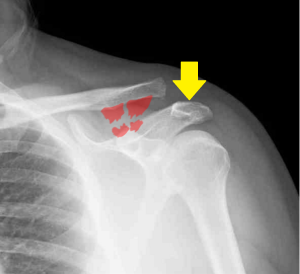

AC joint separations are diagnosed by clinical examination and x-ray (Figure 5).

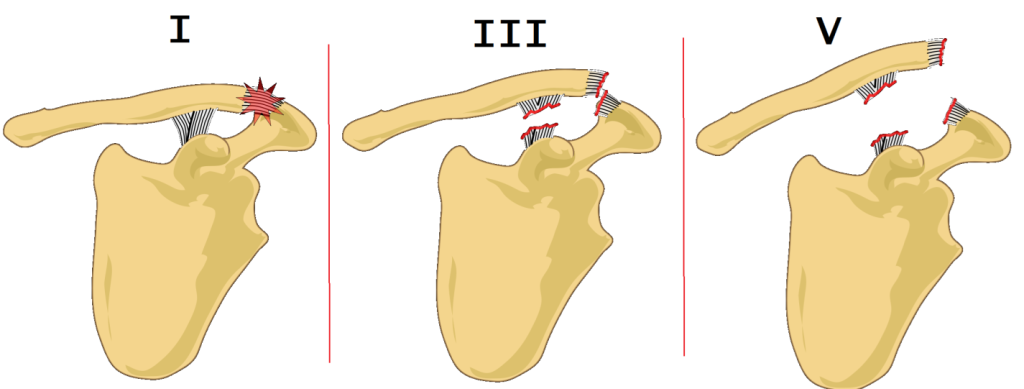

They are classified according to the amount and direction the physical separation seen between the acromion and the clavicle (Figure 6).

- Type I injuries are sprains or partial tears of the AC joint capsule without instability and have no visible deformity.

- Type II injuries include complete tears of the AC ligaments without involvement of the coracoclavicular ligaments. These injuries are characterized by slight displacement of the acromion from the clavicle.

- Type III injuries represent tears of both the AC and coracoclavicular ligaments and are associated with complete displacement of the joint.

- Type V injuries are basically Type III injuries with more marked displacement.

- (The rare Type IV injuries involve posterior displacement of the distal clavicle and Type VI injuries include inferior displacement of the distal clavicle underneath the coracoid process.)

It may be more useful to think of this classification as containing three broad categories: “nondisplaced”; “partially displaced”; and “displaced”.

Radiographic assessment of the AC joint is best performed with bilateral anteroposterior (AP) views. This allows for side to side comparison of coracoidclavicle distance.

Axillary views can determine the amount of motion occurring in the sagittal plane, but these x-rays are also useful to make sure there is no glenohumeral joint disruption. In general, it is worth remembering that three views of the shoulder (AP, lateral and axillary) should always be obtained.

An AP x-ray with a 15-degree tilt cephalad (a so-called Zanca view) allows for a better visualization of the AC joint by removing the scapula from view.

AP radiographs while the patient is holding weight in each hand (“stress radiographs”) can demonstrate an injury that is otherwise not apparent (especially separating a Type II injury from Type III injury), however this has the potential of causing further damage to an injured joint. Moreover, many physicians would offer the same treatment – non-operative management – independent of whether stress causes further displacement. This illustrates a key point: even a simple radiograph is a diagnostic test, and a diagnostic test should be obtained if and only if it will alter management.

In osteolysis of the distal clavicle, there may be widening of the AC joint due to complete loss of bone at the tip of the clavicle. The bone that remains may be tapered and osteopenic (faded, on x-ray) or have erosions and cysts. All of these findings reflect incomplete loss of bone.

Osteoarthritis can also be diagnosed with radiographs demonstrating joint space narrowing or growth of bone spurs.

Epidemiology

AC joint injuries represent about 10% of shoulder injuries in the general population, with nearly 50% of these injuries occurring in athletes. Nearly 90% of these injuries are low-grade and usually resolve within a week or two.

Osteoarthritis of the AC joint affects 5% of the adult population. Symptomatic arthritis of this joint is commonly seen in weightlifters.

Differential Diagnosis

A fracture of the distal clavicle can present similarly to AC joint separation, leaving the ligaments attached distally to the fracture site. Distal clavicle fractures can be ruled out with diagnostic x-rays although the two can occur simultaneously after major trauma.

It must be recalled that the physis (growth plate) of the distal clavicle is the last bone to fuse, and therefore up until age 25, a shoulder separation may actually be a growth plate fracture.

The very rare fracture of the base of the coracoid also presents with a superiorly displaced distal clavicle, but distance between the coracoid and the clavicle remains normal, about 10 mm, in most cases.

Red Flags

Although a majority of AC joint separation injuries are benign, the joint is not far from very important structures, including the subclavian vessels, brachial plexus and the lungs. High energy mechanisms of injury, especially with displacement, demand thorough scrutiny of physical examination and imaging studies to ensure that a pulmonary or neurovascular injury is not missed.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

If the AC joint is not dislocated, non-operative treatment is recommended. Both Type I and II injuries can be managed with the use of a sling; the duration of course may be longer for an injury of greater severity.

Operative management is recommended for marked superior displacement, or any displacement posteriorly or inferiorly – that is Types IV, V and VI.

Operative management may be selected for some patients with complete but not exaggerated superior displacement, namely a Type III injury.

Surgery typically involves joint reduction, ligament repair or replacement with a graft, and reconstruction of the fascia that overlies the trapezius and deltoid muscles. Currently, sutures or combined suture and button constructs are utilized to hold the clavicle in place after acute injuries to allow for primary healing, or in chronic cases until a tendon graft has had ample time to heal. Historically, screws were used for this purpose; however, they have fallen out of favor due to hardware complications and worse outcomes (Figure 7).

Post-operatively, patients typically use a sling for immobilization for six weeks. Active range of motion is initiated eight weeks after surgery, and resistance rehabilitation is started at the 12th week.

Treatment of osteoarthritis of the AC joint involves activity limitation and medication. Some may find temporary relief with injections of glucocorticoids into the joint space, however this relief is usually short-lived. In addition, it may be difficult to get a needle around the osteophytes (bone spurs).

A particularly symptomatic patient with arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint can be treated with resection, that is simply cutting out a small sliver of the distal clavicle and allowing a fibrocartilage scar to replace it.

The most common complication of AC joint separation is residual pain or limitations of mobility. This can affect 30% to 50% of patients.

Treatment of arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint with resection can provide good relief, as long as care is taken to not remove too much medial clavicle (which, by involving the ligaments, might produce instability).

Risk Factors and Prevention

The single biggest risk factor for separation is in participation of contact sports (football, hockey, rugby).

Likewise, the risk factor for osteoarthritis of the AC joint is participation in activities that load the joint.

Neither of these categories of risk factors are particularly amenable to modification, though protective padding around the shoulders for football and ice hockey players (or for any sports that involves routine tackling and falling) has intuitive appeal.

Miscellany

Although the clavicle appears to be elevated in the case of an AC joint separation, what is seen, in fact, is acromial depression (due to the weight of the arm).

Key Terms

Acromioclavicular joint, coracoclavicular joint, synovial joint, Rockwood classification

Skills

Interpret classic history and physical exam findings to confirm diagnosis. Apply the classification of AC injury to formulate a treatment plan.