17 Disorders of the Extensor Mechanism of the Knee

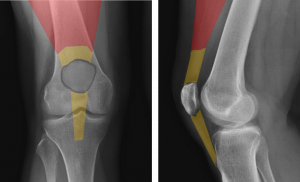

The extensor mechanism of the knee comprises the quadriceps muscle and tendon, the patella, and the patellar tendon (also known as the infra-patellar ligament). Disruption of any of these components impedes a person’s ability to actively extend the knee or resist passive flexion. Such injuries are therefore incompatible with normal walking and standing. Failure of the quadriceps or patellar tendon is often, but not always, preceded by painful tendinopathy.

Structure and Function

The quadriceps muscle, as its name implies, is composed of four muscles: the vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis and rectus femoris (see Figure 1). All but part of the rectus femoris originate on the femur itself. These muscles converge at a point approximately 5 cm proximal to the patella to form the quadriceps tendon. The quadriceps tendon has multiple layers, with the rectus femoris as the most superficial layer, the vastus medialis and lateralis as the middle layer, and the vastus intermedius as the deepest layer. The superficial layer is well vascularized; however, there is a hypovascular zone in the middle and deep layers approximately 1-2 cm proximal to the patella. This is the most common site of rupture.

The patellar tendon originates at the distal end of the anterior aspect of the patella and inserts on the anterior aspect of the tibia at the tibial tuberosity. The tendon most commonly tears at its origination on the patella.

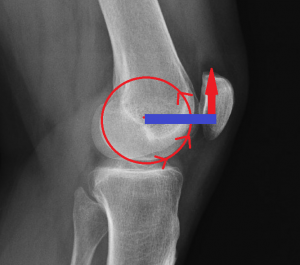

The function of the patella is to increase the distance between the extensor mechanism and the center of rotation of the knee as seen in the sagittal plane. This distance creates a so-called moment arm; the greater the distance, the greater the moment arm and, in turn, the greater the leverage (see Figure 2). Without a patella, the effective strength of knee extension is at least 30% decreased.

Patient Presentation

Tendinopathy

The chief complaint of quadriceps or patellar tendinopathy is pain, localizing to the damaged structure. Because these tendons are directly under the skin there is often little ambiguity if the pain is focal: patients can point and say, “it hurts right there”. Tendinopathy can coexist with patellofemoral disorders or bursitis, which sometimes leads to a more nonspecific presentation.

A thorough patient history and physical examination are critical components in diagnosing disorders of the extensor mechanism. Documenting patients’ athletic participation as well as whether pain increases with activity are important.

Patients with tendonitis commonly report an insidious onset of sharp anterior knee pain. Patients typically report an increase in pain with activity. Patients may also complain of pain when seated for long periods of time.

Both patellar tendonitis and infrapatellar bursitis are painful to the touch. Patellar tendonitis can be differentiated from infrapatellar bursitis in that the latter condition is painful with side to side pinching of the skin as well (Figure 3A and 3B).

Tendon Rupture

Patients with patellar tendon rupture may report direct trauma (fall) or injury while jumping with the knee bent and the foot planted. Patients will report feeling a tearing or popping sensation at the time of the event.

Quadriceps tendon rupture due to degenerative changes classically presents with a report of a popping or tearing sensation after falling backwards with the foot caught on the ground. Patients may report a history of anterior knee pain before tendon rupture, likely due to tendinopathy. Rupture in athletes typically occurs during eccentric quadriceps contractions, which occur when landing from a jump or changing running directions at high speeds.

Physical exam performed acutely after quadriceps or patellar tendon rupture will reveal swelling and tenderness proximal or distal to the patella, respectively. A palpable defect can often be palpated within the torn tendon.

When either tendon is completely torn patients are unable to extend the knee, perform a straight leg raise, and often cannot bear weight on the injured leg. (That is because in stance phase, the center of gravity of the body is behind the center of rotation of the knee joint and tends therefore to flex it. In ordinary circumstances, the knee does not buckle, and the patient is able to stand upright only because of the resistance to flexion provided by the extensor mechanism.)

When the tendons are partially torn (or if there is sufficient retinacular tissue still intact), patients might still be able to hold the knee in full extension.

Objective Evidence

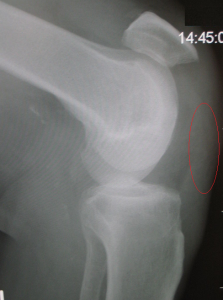

Plain radiographs should be obtained to rule out fractures if the mechanism suggests that one may be present. Radiography can also help identify a soft tissue injury, as a lateral view x-ray will confirm displacement of the patella. A distally displaced patella (patella baja) and a proximally displaced patella (patella alta (see Figure 4) are signs of quadriceps and patellar tendon rupture, respectively.

If there is any question whether a disruption is present, an MRI may be helpful. MRI cannot only differentiate between a partial and complete tear, it can localize the injury and provide information about the quality of the surrounding tissue (Figure 5). This latter information may be useful for surgical planning.

Epidemiology

While quadriceps and patellar tendonitis are common, both quadriceps tendon and patellar tendon ruptures are rare.

Quadriceps tendon rupture occurs predominately in males. Over 80% of tendon ruptures occur in adults over the age of 40 due to degenerative changes; however, younger athletes are also susceptible to tendon rupture due to direct trauma or excessive eccentric joint loading.

Injuries to the patellar tendon are more common in patients under 40 years old. This condition occurs more in jumping athletes, particularly basketball and volleyball players; however, soccer players commonly experience this injury due to the repetitive forces placed on the extensor mechanism. While bilateral rupture for both is possible, patients typically present with unilateral injury, commonly in the dominant leg. Quadriceps ruptures can be seen more commonly in patients with chronic renal disease, patients with diabetes mellitus, or in patients taking steroids for the management of other medical conditions.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for focal anterior knee pain includes not only tendinopathy but patellofemoral pain syndrome (with or without patellofemoral arthrosis) and bursitis. Of course, these can coexist. A detailed physical examination with imaging can usually differentiate between these diagnoses.

The differential diagnosis for an inability to extend broadly divides into failure of the extensor mechanism or mechanical blockage within the knee joint. These usually can be defined easily by assessing passive motion. A displaced meniscus tear, for example, will impede both active and passive motion, whereas a torn quadriceps will have only limitations on active motion. Incomplete tears, however, may be sufficiently painful that it is difficult to assess passive motion in all instances.

Once it is determined that the extensor mechanism is disrupted, the differential narrows to injuries of the quadriceps tendon, the patella itself and the patellar tendon. Bony injuries in the absence of a direct blow can be assumed absent, though at times patients fall after they tear their tendon making the history a little less clear. X-rays are therefore helpful. Films obtained with the knee in flexion can also indirectly document a soft tissue injury as the patella will be in an abnormal position. Noting the patient’s age (again, age over 40 is likely to implicate the quadriceps, and age under 40, the patellar tendon) in addition to performing a physical examination may pinpoint the problem more exactly.

Red Flags

In general, tendon injuries do not herald other problems, though the presence of one tendon injury may foreshadow another, and of course tendinopathy itself may suggest an impending rupture.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

Tendinopathy

Because tendinopathy is often an overuse injury, a good first line treatment is relative underuse. Dialing back on activity may allow the body to heal the tendon lesion.

Complete immobilization is not recommended, as this may produce stiffness and atrophy. Physical therapy is intuitively appealing, but there remains no consensus on the best exercises nor the duration of treatment. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may also be prescribed; however, these should be reserved for the first 7-14 days after injury as long-term NSAID use has not been proven to be beneficial and may negatively affect tendon healing.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections have been touted as a promising therapy but as of 2019 have to be labeled as unproven. Steroid injections are not recommended, as they may increase the risk for tendon rupture.

Ice friction massage and isometric flexion stretching may be helpful for patellar tendonitis. (If the knee joint is passively flexed while the patient isometrically contracts the quadriceps, any stretching will be within the patellar tendon itself.)

At times, patellar tendinopathy does not resolve clinically and surgical debridement is indicated.

Non-operative treatment is successful in most patients with tendonitis; however, a small fraction of patients do not respond to non-operative treatment and require surgical debridement. This procedure is successful in more than 75% of cases.

Rupture

For patients with complete rupture of either the quad tendon or patellar tendon, operative repair is indicated to restore normal knee function. That is because even if the tissue were to heal otherwise, the soft tissue will be elongated, and an extensor lag (an inability to fully extend) may result. Also, at the time of operation poor quality tissue can be excised.

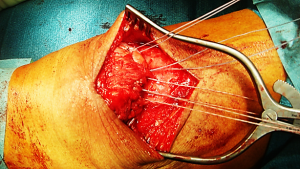

In general, surgical repair (Figure 6) uses a midline incision over the knee, and the torn tendon is identified, debrided and secured to bone. (This may use suture anchors or sutures passed through holes drilled within the patella.) Post-operatively, the patient can weight bear with the leg immobilized in extension. Early range of motion exercises are performed, and after 6 weeks the brace is removed and physical therapy is begun. Therapy to strengthen the knee and improve range of motion is continued usually for 3-4 months post-operatively. Full recovery is typically 4-6 months after surgical treatment.

Non-operative management might be reasonable for partial tears of either tendon. Initially patients may be immobilized with the leg in extension for three to six weeks, with weekly follow-up. Immobilization is gradually discontinued when the patient is able to comfortably perform a supine straight leg raise. Physical therapist-guided rehabilitation is instituted to further recovery. Patients should be counseled on the risk of re-injury.

The outcomes following surgical repair for quadriceps and patellar tendon ruptures are good, though often imperfect. Some patients report persistent pain, decreased range of motion and weakness. Nevertheless, by any fair measure, these patients are still markedly better than they would have been without the treatment. (Indeed, the net benefit from surgical treatment of a complete extensor mechanism disruption is among the highest of any orthopedic procedure.)

Delayed operative treatment often leads to worse outcomes.

Risk Factors and Prevention

Risk factors for patellar tendon injury include a high body mass index (BMI), a large abdominal circumference, limb-length discrepancy, and flatfoot arch. Weak quadriceps muscles and low flexibility of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles are other factors that may contribute to patellar tendon injury. Additionally, sports involving a lot of jumping, particularly basketball and volleyball, have an increased incidence of patellar tendon injury compared to non-jumping sports.

There are numerous risk factors for degenerative quadriceps tendon rupture including increased age, increased BMI, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndromes, hyperparathyroidism, polyneuropathy, anabolic steroid abuse, chronic or acute corticosteroid use, and fluoroquinolone use.

Miscellany

The patella is a sesamoid bone within the distal tendinous expansion of the extensor mechanism, however it is convenient to think of the quadriceps inserting onto the patella and then the patella itself connecting to the tibia. On this basis, some may consider the patellar tendon to actually be a ligament – soft tissue connecting bone to bone – giving rise to the alternative name for this structure: the infrapatellar ligament.

Key Terms

Extensor mechanism, quadriceps muscle, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, quadriceps tendon, patella and patellar tendon

Skills

Recognize the cause of extensor mechanism disruption on plain radiographs. Differentiate between active and passive loss of extension on physical examination, and localize disorders of the extensor mechanism.