10 Disorders of the Glenoid Labrum

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous rim attached around the margin of the glenoid cavity that serves to deepen the cavity. (The glenoid fossa of the scapula is relatively shallow, contacting at most only a third of the head of the humerus). The labrum is triangular in shape with a broad base and is fixed to the glenoid tapering to a thin free edge. The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii blends with the labrum at the apex of the glenoid. Labral tears may result from acute injury, especially when the humeral head dislocates or subluxates, but also from traction via the biceps. Many labral tears are degenerative and are discovered incidentally on MRI.

Structure and Function

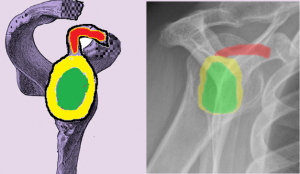

The major shoulder joint is the glenohumeral joint, at which the humeral head articulates with the glenoid cavity (fossa or socket). Because the humeral head is larger than the fossa – the socket covers only a quarter of the humeral head – it is not very stable. To augment stability, a circumferential rim of fibrocartilaginous tissue attaches to the glenoid fossa and thereby increases the contact between the two sides of the joint (Figure 1).

The labrum may be torn acutely, as in a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation. Anterior dislocations often cause an avulsion of the anterior labrum, called a Bankart lesion.

There are two main theories to explain sub-acute tearing of the labrum. The first theory suggests that if the humeral head starts to subluxate (as it might tend to do, for example, if the capsule were lax), the biceps tendon would contract to constrain the humerus. Such repetitive contraction stretches the superior glenoid labrum. A second theory proposes that repeated motion results in cyclical compression and microtrauma to the labrum directly.

When a labral tear is above the “equator” of the glenoid it is called a SLAP tear: Superior Labrum, Anterior to Posterior.

SLAP tears are common among athletes playing a sport with high force overhead arm motion (e.g. tennis players and baseball pitchers).

A posteriorly directed force with the arm in a flexed, internally rotated and adducted position, e.g. weightlifters’ bench press or football line blocking, can damage the posterior labrum

The proximal biceps tendon can also tear, independent of the labrum. The long head of the biceps is vulnerable to tearing, as it makes sharp turns as it courses out of the shoulder joint and down the arm. Tears are more common if there is stenosis of the bicipital groove or if there is a rotator cuff tear (perhaps placing additional demands on the biceps as a humeral head depressor).

Patient Presentation

Acute tears are associated with overt trauma, such as falling hard onto an outstretched arm.

The symptoms of sub-acute labral tears include non-specific deep shoulder pain, a sense of catching or locking (due to a flap of loose cartilage), and perceived instability (which may or may not be reproduced on exam). There may be non-specific symptoms such as decreased range of motion or loss of strength. Symptoms tend to be aggravated with reaching overhead or across one’s body.

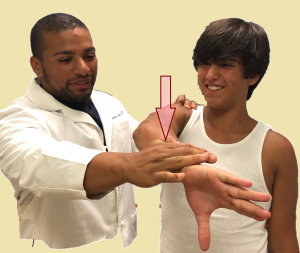

No single physical sign or test has been shown to have both great sensitivity and specificity for SLAP tears. In O’Brien’s active compression test, the patient stands upright with the affected arm flexed 90° and adducted 15° medial to the sagittal plane of the body. With the arm internally rotated, the examiner pushes the arm downward. The test is then repeated with the forearm in maximal supination. A positive test result is recorded when pain elicited by the first maneuver is decreased by the second maneuver (Figure 2).

Isolated degenerative disease of the proximal biceps tendon presents with symptoms similar to rotator cuff disorders, but with the pain sometimes located in the bicipital groove.

Speed test’s (Figure 3) is positive when there is pain in the proximal biceps produced with forward elevation of the shoulder with the elbow extended and forearm supinated. Yergason’s test (Figure 4) will produce pain in the biceps groove when a patient with biceps pathology attempts to actively supinate against the examiner’s resistance.

Objective Evidence

Because the labrum and proximal biceps are soft tissues, they are not seen on plain radiography. Accordingly, x-rays are often not informative when these structures are damaged.

MRI can be diagnostic for labral tears (Figure 5), but both sensitivity and specificity increases with the injection of contrast (creating a so-called MRI-arthrogram).

A conventional MRI might show an associated paralabral cyst (Figure 6), offering a hint that there is a labral tear (that is not seen explicitly).

Epidemiology

There are no firm data on the prevalence of labral disorders, because many people do not seek medical care. It is known that starting at about age of 35, the superior labrum is less firmly attached to the glenoid, leading to anterior-superior rim tears, and that at about age 60 internal age-related degenerative changes are more common.

Differential Diagnosis

The main competing diagnoses (which may be present concurrently) are rotator cuff tears or degeneration and shoulder instability.

Red Flags

There are no particular red flag diagnoses for the symptoms associated with labral disorders.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

Initial treatment options for a torn labrum generally include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and a period of rest. Physical therapy is then initiated to strengthen the rotator cuff muscles.

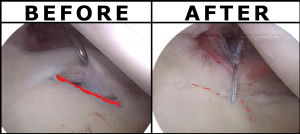

Surgical intervention depends on the type of labral lesion, but an arthroscopic repair is most commonly used (Figure 7). Frayed labral tears are treated with debridement.

Damage to the biceps anchor can be treated with arthroscopic fixation of the superior labrum, but patients 45 years of age or older are prone to stiffness if the tear is repaired. Accordingly, fixation is considered relatively contraindicated in these patients.

Proximal biceps tendinopathy is also first treated with NSAIDs and therapy. A steroid injection near, but not in, the tendon may be helpful. Should that not work, surgical release (tenotomy) or repair to the humerus (tenodesis) may be chosen. Tenotomy may cause an asymmetric bulging of the biceps in the affected arm. Tenodesis may be associated with pain in the bicipital groove. This complication may be prevented by attaching the tendon to the bone in a more inferior position, i.e. in the sub-pectoral region of the humerus.

Most patients with labral tears will return to their pre-injury level of shoulder function, with slightly worse results seen among overhead throwing athletes.

The most common overt complication for surgical treatment is an injury to nerves around the shoulder, but this is rare (less than 1% of cases) and usually resolves within 6 weeks.

Some patients, especially older ones, have lost motion, though this may be ameliorated with therapy once the tissue repair has healed.

Risk Factors and Prevention

The main risk factors for labral disorders are sports demanding repetitive overhead motion (baseball, tennis, swimming) and increasing age (due to degenerative changes in the tissue as well as risk of falls).

These risk factors are not really amenable to change, but strengthening of the rotator cuff muscles, adequate warm-up before activity, and adequate rest intervals between episodes of intense activity can all be defended as common sense.

Miscellany

About 1% of people have a congenital glenoid labrum variant where the anterosuperior labrum is absent. This variant is known as a “Buford complex”.

Key Terms

Labrum, SLAP lesion, Bankart lesion, rotator cuff, arthroscopy, torn biceps

Skills

Categorize MRI findings of a torn labrum. Perform physical exam to identify labral pathology.