20 Meniscus Tears

The medial and lateral meniscus (plural: menisci) are crescent-shaped pieces of fibrocartilage that lie atop the tibia to cushion its contact with the femur and help stabilize the knee. Because these functions subject the menisci to high forces, the menisci are subject to tearing. Both acute traumatic events and simple degeneration can be responsible for tearing. Many patients with degenerative tears of the meniscus have no symptoms, though some have focal joint line pain or a sense of catching. The menisci themselves have very little intrinsic capacity for healing, and thus persistently symptomatic tears are treated with partial meniscectomy (removal), though tears near the capsule can be repaired.

Structure and Function

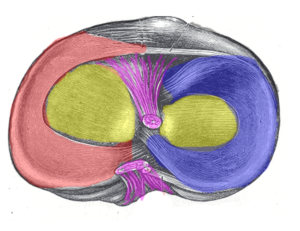

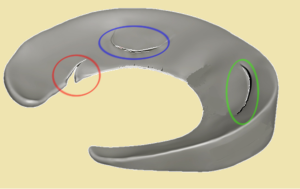

The medial and lateral menisci are thin pieces of fibrocartilage that sit atop the tibial plateau (Figure 1). The menisci are C-shaped when viewed in profile, tapering from about 5mm in height near the capsule to a central edge.

The menisci also help lubricate the knee joint. Beyond that, the meniscus is thought to have three mechanical functions. First, it allows the rounded femoral condyle to make broader contact with the tibia, thereby dissipating pressure. (Because pressure is equal to force/area, greater area leads to lower pressure for a given force) (Figure 2).

In addition, because the menisci are more elastic than articular cartilage, they also function as shock absorbers.

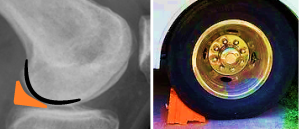

Last, the menisci (especially on the medial side) help stabilize the knee, by a so-called chock block effect (Figure 3).

There are some important differences between the medial and lateral meniscus. The medial meniscus is more firmly attached to the tibial condyle by the deep medial collateral ligament (MCL); the lateral meniscus is relatively mobile. Thus, the medial meniscus is a more important stabilizer. Because the medial meniscus is tethered, it is also more susceptible to injury and is torn approximately three times more often than the lateral meniscus.

The lateral meniscus is separated from the capsule at the popliteal hiatus, an aperture through which the popliteus tendon courses into the joint.

Only the most peripheral part (about 3 mm) of the menisci have blood vessels and thus meniscal tears have little inherent capacity to heal. Because the blood supply enters from the capsule at the periphery (the so-called red zone), some tears there might heal; central tears (called “white zone” tears owing to the lack of blood supply) are thought to have no healing potential.

The menisci also have no pain sensors within them. Thus, to the extent that meniscal tears are painful (and many are) it is due to irritation of the nearby synovium or capsule.

Patient Presentation

Traumatic tears of a healthy meniscus normally occur in active young adults who present with pain and swelling after an acute event. A classic report is a twisting injury with the foot planted and the knee flexed, though this is certainly not required.

There may be an effusion of variable size. Pain typically localizes to the joint line. Incomplete range of passive motion suggests a displaced tear. A displaced tear usually blocks the final 20 degrees of terminal extension, with reasonably free motion in the flexion arc beyond that. Although some motion is possible, this condition is termed “locking” – though “blocking” may be a more apt word.

Meniscal tears can be seen in conjunction with other injuries (such as a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament) and the presentation may be dominated by that other condition.

Degenerative tears normally are found in adults over the age of 40. The presentation is similar to that of arthritis, but the pain from the meniscus is more likely to be focally on the joint line, with or without mechanical symptoms such as catching.

The physical exam must note the pattern of gait, alignment, range of motion and the presence of an effusion. Integrity of the ligaments must also be assessed.

There are specific tests for diagnosing a meniscal tear on examination, but all are based on subjective responses. The best test is assessing for joint line tenderness (Figure 4). This too is subjective, but it is simple. Tenderness above or below the joint line suggests that a meniscal tear is not responsible for symptoms.

Objective Evidence

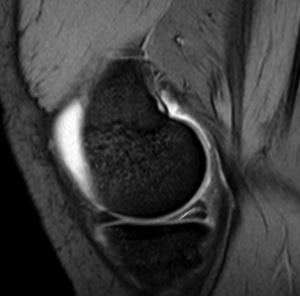

MRI is the gold standard in terms of accurately diagnosing a meniscus tear. A meniscal tear will manifest as increased signal within the meniscus that extends to the tibial or femoral articular surface (Figures 5 and 6). Signal change confined within the meniscus itself (that is, the signal change that does not cross the triangular borders of the meniscal surfaces) represents internal degenerative change.

The use of MRI is perhaps best understood by reminding oneself that it is a diagnostic test, and like all such tests, should be used if and only if the results could affect the treatment of the patient. Contrary to popular belief, MRI is not particularly expensive (it is perhaps double the cost of x-rays, but not much more), it is painless and non-invasive and has no known biological risks. Given that, it should be used frequently, or at least more frequently than expensive, painful, invasive and risky tests. The main downside of an MRI is the discovery of an incidental and irrelevant finding, one that will provoke unnecessary care or unnecessary worry. Simply: all patients for whom MRI is indicated should have one – but only them.

Because degenerative tears are so common, MRI should be avoided in a patient with a suspected degenerative meniscal tear – unless the test will affect management. At the least, weight-bearing x-rays should be obtained first to check for arthritis. Also, the patient should confirm interest in treatment should the test come back positive. In the setting of degenerative joint disease, a practitioner should have a high threshold for obtaining an MRI.

In the setting of an acute injury sustained by a young athlete, a practitioner should have a very low threshold for obtaining an MRI. Swelling and pain may limit the accuracy of the exam, and because it would be tragic to not detect a repairable injury before it progresses to an irreparable one (for example, a displaced but otherwise intact meniscal fragment that gets pulverized by the femoral condyle in its displaced position).

Meniscal tears are described by their configuration (Figure 7).

- A radial tear starts on the interior free margin of the meniscus and propagates peripherally,

- A horizontal cleavage tear lies within the meniscal tissue, parallel to the tibial plateau,

- A longitudinal tear is a top-to-bottom tear in the meniscus, the courses parallel to the capsule, perpendicular to the plateau.

Epidemiology

Individuals who participate in sports are at the greatest risk for acute meniscal tears. Those who participate in sports where sudden change of movement is a critical component of the game (i.e. football, soccer, basketball) are at the most risk.

Degenerative tears are extremely common in older patients and often asymptomatic. The presence of a tear on MRI should not be assumed to be the source of symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis

Patients suspected to have an acute meniscus tear may have instead, or in addition, a collateral or cruciate sprain; an osteochondral injury; a loose body; or a disorder of the patello-femoral joint.

Patients suspected to have a chronic meniscus tear may have instead, or in addition, degenerative joint disease. Indeed, the presence of some degenerative joint disease can be assumed and the differential diagnosis pays attention to the relative contribution of each.

Red Flags

When evaluating the knee joint for a suspected meniscus tear, pay specific attention to detect associated injuries: a mechanism of injury that could tear the meniscus is a red flag for cruciate and collateral sprains, and vice versa.

A large effusion in young, active males may be a sign of gonorrhea. A detailed history is helpful here.

A locked knee suggests displacement of the meniscus into the notch, a so-called bucket handle tear.

A medial meniscal tear in a patient with a stable knee despite a known history of an anterior cruciate ligament deficiency is at high risk of developing symptomatic instability because of the meniscal tear. As such, a meniscal tear in this setting is a harbinger of impending problems and may provoke a need for anterior cruciate ligament treatment as well.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

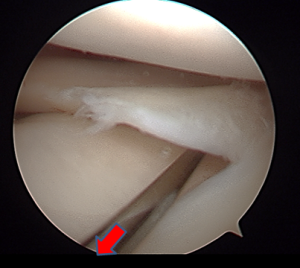

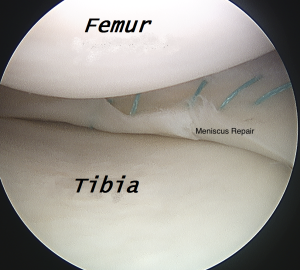

Displaced tears that prevent full motion should be considered for urgent surgery. The recommended procedure is an arthroscopy, with either a repair or removal of the tear, based on the intra-operative findings (Figures 9).

If the patient has full range of motion, urgent surgery is not indicated, unless imaging and the clinical scenario suggests a potentially repairable tear. (Tears in the outer 25% of the meniscus, in the red-red zone, have healing potential.) It is important to not miss the chance to treat a repairable tear while it is still repairable.

If the patient is planning surgery but deferring it (as may be done for a student waiting for an academic break in the calendar), protective bracing may be helpful.

Some meniscus tears, even acute ones, might become asymptomatic without surgery. Thus, it is reasonable for a patient to choose a trial of rest and anti-inflammatory medications, especially if the tear does not appear amenable to repair. The need for an arthroscopic meniscectomy will declare itself by a failure for symptoms to resolve.

In older patients, a course of physical therapy, working on strength and the maintenance of full motion, is reasonable. In one study from England, many patients on a waiting list for meniscal surgery cancelled their procedure before being called, as symptoms resolved spontaneously.

If the entire meniscus is torn and has to be removed, a meniscal transplant may be indicated in young patients with normal alignment and no arthritis.

The overall success rate of meniscal repair depends on the status of the ACL. If the ACL is intact, the meniscal tear will heal 60% of the time. If the ACL is injured, the meniscal tear will heal in 90% of cases if the ACL is reconstructed but in only 30% of cases if not. After removal of a large part of a meniscus, some patients have continued pain, likely due to the loss of the shock absorber effect. In rare cases, menisucs allograft transplantation can be performed, preparing a size-matched meniscus from a cadaver and securing it within the knee. Ideally, this operation is performed before any arthritic changes are found.

Risk Factors and Prevention

The general risk factor for a meniscus tear is participation in sports, especially events that require high intensity shifting and change of direction.

A more focal risk factor is knee instability, especially a history of anterior cruciate ligament injury. With an ACL deficiency, the medial meniscus is called upon to help stabilize the knee, and is thus subjected to greater than normal forces.

There are no proven methods of prevention.

Miscellany

For many years, the menisci were thought to be vestigial, serving no specific function. Thus, surgeons routinely removed them. In 1948, Thomas John Fairbank published a paper, “Knee Joint Changes After Meniscectomy” in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery reporting that total meniscectomy produced squaring of the femoral condyles, peaking of the tibial spines ridging, and joint space narrowing. These are now known as Fairbank’s changes.

The word meniscus comes from the Greek, mene, meaning moon. This is the same root that gives us the medical term “menstrual”.

Key Terms

Medial and lateral menisci, meniscal tear, bucket handle tear

Skills

Identify locking, joint line tenderness and effusion on examination. Recognize meniscal tears on MRI. Recognize when MRI is indicated to detect meniscal tears.