1 Stress Fractures and the Female Athletic Triad

The Female Athlete Triad was initially defined as the constellation of three interrelated clinical entities typically found in active young women: amenorrhea, osteoporosis, and disordered eating. The definition has now been broadened to recognize that each component of the triad exists on a spectrum. Thus, menstrual irregularities (without amenorrhea), low bone mineral density (without full-blown osteoporosis) and deficits of energy availability due to a deficient nutrition (without a formal diagnosis of an eating disorder) may be sufficient to prompt this diagnosis. Notably, the Triad can appear when there is not enough caloric intake to balance caloric expenditure, independent of whether that imbalance is intentional or unintentional. For example, many runners do not realize how much to increase intake as they ramp up their training.

The Female Athlete Triad can have significant medical ramifications outside of musculoskeletal medicine – notably gynecological and psychological. Patients with the Female Athlete Triad usually come to attention of musculoskeletal practitioners because of stress fractures: skeletal damage caused by repetitive loading forces that exceed the bone’s mechanical resiliency.

The Female Athlete Triad is also relevant to musculoskeletal medicine in that even without a stress fracture, patients with this condition may fail to attain an optimal peak bone mass in adolescence –the time of maximal bone formation– and thus place themselves at higher risk for osteoporosis later in life.

Structure and Function

Female athletes, especially those who participate in an activity that values a thin physique, may choose to eat too little or exercise too much. In the extreme, some may starve themselves (anorexia nervosa) or overeat and purge (bulimia).

Insufficient nutrition has two important consequences for bone health. For one thing, a calcium deficiency may be present. Also, decreased body fat is associated with decreased estrogen levels as well. Low estrogen can be recognized by amenorrhea, but its deficiency can also cause clinically silent damage to the bone. Estrogen is a potent mediator of both osteoclast and osteoblast activity. Without appropriate levels of this hormone, bone remodeling is disrupted.

Bone remodeling is the process that repairs the (micro)damage induced by regular activity. It also adjusts the bone’s architecture to better withstand the mechanical stresses placed on it.

Remodeling is achieved through the coupled action of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Osteoclasts resorb bone, and osteoblasts synthesize new bone matrix which then becomes mineralized.

Activities that apply cyclic loading forces can lead to the formation of microfractures. (Running is the prototypical “cyclic loading forces” activity but not the only one; rowing and throwing are commonly seen causes as well.) When the rate of damage accumulation becomes greater than the rate of remodeling, these microfractures can lengthen and coalesce, resulting in a stress fracture.

Patient Presentation

Patients with stress fractures will classically present with insidious onset of pain that acutely worsens with high impact activity and improves with rest. Pain onset is often several weeks after a notable increase in a familiar physical activity and is not associated with a specific injury. For example, a runner who recently increased her training from 5 to 10 miles per day may present with new symptoms.

Any female athlete who presents with a stress fracture should be questioned for the presence of factors associated with the Female Athlete Triad. The patient should first be asked about activities and nutrition. As a first approximation, athletes should eat about 45 kCal per Kg of lean body mass, in addition to the sports-specific energy demands (e.g., approximately 100 kCal for every mile ran). In addition, they should be asked about their menstrual history and use of birth control pills. A history of prior stress fractures, weight changes or other diseases that may affect bone health (e.g., thyroid disease) should also be reviewed.

The first physical finding to assess is the body mass index (BMI). BMI is defined as the body mass divided by the square of the body height. Because self-reporting is imprecise, formal measurement should be made. According to the 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement, a BMI below 18.5 kg/m2 represents moderate risk and a BMI below 17.5 kg/m2 is high risk.

On physical exam, stress fractures often have no objective findings at all. Point tenderness or swelling may or may not be present. If there is a high index of suspicion, a thorough exam of the implicated bone is warranted. The 3-point fulcrum test is useful in identifying femoral shaft stress fractures and is considered positive if pain is elicited. Additionally, a calcaneal squeeze test that elicits pain can indicate a calcaneal stress fracture of the foot (See Figure 1).

Soft, thin hair on the extremities (so-called “lanugo”), scarred knuckles, and parotid gland enlargement are physical exam findings seen in patients with anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Bradycardia and low blood pressure can be signs of malnutrition or low energy availability, but this is difficult to differentiate from a physically fit athlete with a slow baseline resting heart rate.

Objective Evidence

In Female Athlete Triad, each of the three components can be assessed independently, which can help guide treatment. In low energy availability states, electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia, hyponatremia, or an acid-base disturbance may be present.

Menstrual disturbances should first be assessed with a urine pregnancy test. Other lab values can provide insight on the functioning of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis including luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone, prolactin, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH).

Assessing bone mineral density with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is critically important for patients with Female Athlete Triad, especially if she has already had a stress fracture. A Z-score less than +1.0 in a young athlete should prompt further evaluation because bone mineral density is expected to be higher in those who regularly participate in weight-bearing activity.

Typically, patients with stress fractures will have normal radiographic findings. Positive findings are more likely to be found several weeks after symptom onset. These findings include cortical radiolucency, periosteal reaction (see Figure 2), endosteal or cortical thickening, and (in the rare case) a fracture line.

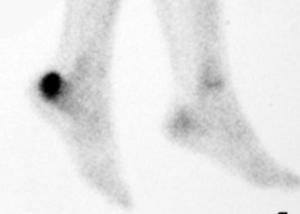

MRI and technetium bone scans are the best diagnostic imaging tests for identifying occult stress fractures (see Figure 3). T1 and T2-weighted MRIs will pick up marrow edema and delineate clear fracture lines. Tc99m bone scan will show focal uptake at the stress fracture site.

Epidemiology

Female Athlete Triad is most commonly seen in adolescents and young adults. Sports in which a thin figure and light weight are competitively advantageous, such as ballet, cheerleading, gymnastics, and cross-country running, are often implicated. Athletes of any sport can develop the condition.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, it is difficult to estimate the true prevalence of the triad as each of the components may be expressed in varying severity. Moreover, not all components are present simultaneously. Beyond that, prevalence is assessed by self-reported (and possibly imprecise) metrics in cross-sectional studies. With that caveat, the frequently used approximation is that 1% of high school athletes have all three components and that the prevalence of at least one component may be as high 50%.

It is also difficult to estimate the true prevalence of stress fractures, primarily because many cases do not present for medical attention. Also, among those fractures that are seen, treatment (in the form of relative rest) is often initiated empirically without objective confirmation. Stress fractures are most commonly seen in weight bearing bones of the leg (e.g. the metatarsals and calcaneus most commonly). They can also occur in the tibia, fibula, navicular, femur and bones of the upper body. Young military recruits are another population where stress fractures are commonly identified, especially within the first several months of their training. In this population these injuries are often called “March Fractures,” and classically occur in the 2nd metatarsal.

Differential Diagnosis

Lower extremity pain in an athlete without a history of overt injury suggests the diagnosis of stress fracture, but this may also be the presentation of a simple muscle strain. Pain that does not get better with rest may suggest more serious conditions such as bone tumors or infection. Radiographs in patients with suspicious symptoms are essential. Because the x-ray presentation of stress fractures, tumors, and infections can be similar, MRI or other advanced testing may be needed as well.

Red Flags

A diagnosis of Female Athlete Triad should be high on the differential when any of the following are present:

- Any female athlete that presents with a stress fracture,

- Body mass index below 20,

- Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea in a competitive athlete,

- Concerning comments about weight gain, weight loss, calorie restriction, or body image.

There should be a high index of suspicion for a stress fracture when any of the following are present:

- An athlete who presents with pain in the lower extremity without a clear history of an injury,

- History of dramatic increase in a specific physical activity,

- Acutely worsening and localizing pain with exercise and significant relief with rest.

The Female Athlete Triad is itself a “red-flag” for the presence of other conditions that may be beyond the expertise of a musculoskeletal medicine specialist. These include gynecological abnormalities, endocrine disorders (e.g. polycystic ovary syndrome, hyper/hypothyroidism), complications of pharmaceuticals (both prescribed and illicit), and psychological disorders. It is critical to make the appropriate referral to a provider with the relevant expertise.

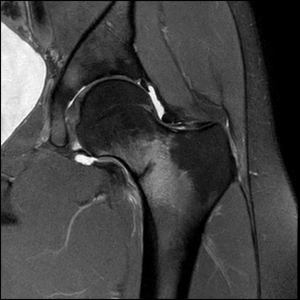

Stress fracture of the superior femoral neck (the so-called “tension side” of the neck) can propagate and displace the femoral head from the shaft. (This contrasts with such fractures on the inferior neck, the “compression side” (see Figure 5), which, should they propagate, will collapse upon themselves.) In turn, such displacement may disrupt the blood supply to the femoral head and cause osteonecrosis. This is a rare complication of a rare condition, but the consequences of missing it can be catastrophic. Thus, a presentation suggesting a stress fracture of the hip demands diligent attention, prompt imaging and referral to an orthopaedic surgeon if the diagnosis is confirmed.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

The primary goal in treating Female Athlete Triad is restoring energy balance, which will help restore menstrual regularity and improve bone mineral density. Nutrition education, modifying diet and physical activity, and partnering with mental health services are important methods in treating energy availability.

Calcium and vitamin D supplementations are also important in restoring bone health. Contrary to recommendations for the older population, bisphosphonates are not recommended in treating low bone mineral density or osteoporosis in patients with Female Athlete Triad, as their use increases the risk of stress fractures.

The treatment goal for Female Athlete Triad is restoring energy balance and improving bone mineral density. Clinical success can be gauged by weight gain and resumption of menses. Screening and early diagnosis of this condition is essential as bone loss during adolescence and early adulthood is not recoverable and impacts the patient’s peak bone mineral density later in life.

The mainstay of treatment of stress fractures is rest and avoidance. Activity is restricted, and athletes cannot return to play until pain subsides, tenderness has resolved, and radiographic findings are negative.

Stress fractures of metatarsals, femoral shaft, and tibial shaft can generally be managed with modified weight bearing. Fractures in the calcaneus and navicular may require a stricter non-weight bearing status.

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) may be considered in elite or professional athletes who require a faster recovery and are at high risk of complications, such as displacement or nonunion.

Operative treatment is also indicated for fractures in locations at high risk of fracture propagation or poor healing, such as on the tension side of the femoral neck or on the anterior cortex of tibia. Surgery is also indicated when non-operative measures have failed.

Persistent weight bearing on a stress fracture may cause arrest of bone healing or lead to a complete fracture, increasing the risk of displacement and nonunion. Stress fractures have an overall excellent prognosis when treated appropriately (operative vs non-operative, non-weight bearing vs modified weight bearing) and the patient is educated on physical activity modification.

Risk Factors and Prevention

Participation in sports that place value on thinness, either for esthetic reasons (e.g. gymnastics) or performance (e.g. long-distance running) may increase the risk of developing the Female Athlete Triad. Another risk factor is playing a sport in which athletes compete in weight divisions (e.g. light-weight rowing).

Lack of nutritional education in a competitive athlete is also a known risk factor.

Prevention of the Female Athlete Triad may be helped by screening and early recognition. Screening can be accomplished during sports physicals with questionnaires or through targeted history-taking. Information such as menstrual history, dietary habits, body image assessment, and eating behaviors can identify females at risk and aid in the diagnosis if Female Athlete Triad is already present.

Athletes with a sudden increase in their level of activity are at risk for stress fracture: the process of bone remodeling is overwhelmed. This can be mitigated by well-conceived training schedule.

Miscellany

The Female Athlete Triad is typically not denoted by the acronym FAT–perhaps because the syndrome is characterized by a lack of fat.

Key Terms

Female Athlete Triad, stress fractures, low energy availability, amenorrhea, bone mineral density, osteoporosis, insufficiency fractures, march fractures, bone remodeling

Skills

Identify athletes at risk of Female Athlete Triad. Obtain the relevant history in a respectful manner likely to elicit complete information. Recognize the signs, symptoms and radiographic findings of stress fracture. Educate the patient on activity modification and strategies to prevent future stress fractures.