Chapter 2: Exercise, Physical Activity, and Sleep

How much of your day do you spend awake versus asleep?

Of your awake time, how much of your day is spent being active versus inactive?

Of the time you spend being active, how much of that time is your heart rate elevated?

How much of your day do you spend strengthening your muscles or stretching?

This chapter is focused on the time of the day you spend active versus inactive, specifically focusing on your physical activity, exercise, physical fitness, and sleep.

The information in this chapter comes primarily from three key research and evidence based reports:

- The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 2nd edition[1]. Note this first edition was published in 2008 and the 2nd edition in 2018.

- The WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour[2]

- The Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030[3]

Chapter 2 Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Describe the difference between Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness.

- Explain the importance of physical activity and exercise for health.

- Identify ways to increase daily physical activity.

- Apply the components of the FITT principle to exercise program design.

- Calculate Target Heart Rate Zone.

- Recognize the importance of sleep.

physical activity, exercise, and Physical Fitness

What is the difference between physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness?

Although often used interchangeably, the terms physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness have different meanings. In short, physical activity refers to any body movement, exercise is physical activity that is planned and structured to achieve physical fitness, and physical fitness refers to how well your heart, lungs, muscles, and joints respond to daily tasks. The detailed definitions[4] for each are:

- Physical activity is any form of bodily movement performed by skeletal muscles that result in an increase in energy expenditure.

- Examples of physical activity:

- Shopping

- Cleaning your house

- Gardening

- Washing your car

- Dancing

- Examples of physical activity:

- Exercise is a form of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and performed with the goal of improving health or fitness. Exercise is purposeful to improve or maintain of one or more components of physical fitness. All exercise is physical activity, but not all physical activity is exercise.

- Example of Exercise:

- Jog for 30 minutes

- Swim 1 mile

- Attend an aerobics class

- Lift weights

- Example of Exercise:

- Physical Fitness is a persons ability to carry out daily tasks with vigour and alertness, without undue fatigue, and with ample energy to enjoy leisure-time pursuits and respond to emergencies. A persons physical fitness is developed by incorporating an exercise routine that specifically develops the components of physical fitness.

-

- The components of physical fitness are categorized into two categories:

- Health-related components of physical fitness: Cardiorespiratory endurance, muscle strength, muscle endurance, flexibility, and body composition.

- Skill-related components of physical fitness: Balance, agility, speed, power, coordination, and reaction time.

- The components of physical fitness are categorized into two categories:

Reflection: Your Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness

Take a moment to reflect on your physical fitness, physical activity, and exercise.

- How would you rate your level of physical fitness? Are you able to carry out daily tasks with vigor and without fatigue? Do you have a lot of energy?

- How does your level of physical activity impact your physical fitness level? Are you active throughout the day?

- What exercise do you purposefully perform that impacts your level of physical fitness? Do you follow an exercise program? Do you include regular exercise that helps your heart and lungs, and helps you become stronger?

health benefits of physical activity and exercise

Why is it important to be physically active and build your fitness? What are the health benefits of physical activity and exercise?

Living an active lifestyle is one of the most important things people can do to improve their health. Physical activity is beneficially for everyone, regardless of age, sex, race, ethnicity, or current fitness level, and benefits can start accumulating with small amounts of, and immediately after doing, physical activity. Being active improves your health in numerous ways.

Children and Adolescents

- Improved bone health (ages 3 through 17 years)

- Improved weight status (ages 3 through 17 years)

- Improved cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness (ages 6 through 17 years)

- Improved cardiometabolic health (ages 6 through 17 years)

- Improved cognition (ages 6 to 13 years)*

- Reduced risk of depression (ages 6 to 13 years)

Adults and Older Adults

- Lower risk of all-cause mortality

- Lower risk of cardiovascular disease mortality

- Lower risk of cardiovascular disease (including heart disease and stroke)

- Lower risk of hypertension

- Lower risk of type 2 diabetes

- Lower risk of adverse blood lipid profile

- Lower risk of cancers of the bladder, breast, colon, endometrium, esophagus, kidney, lung, and stomach

- Improved cognition*

- Reduced risk of dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease)

- Improved quality of life

- Reduced anxiety

- Reduced risk of depression

- Improved sleep

- Slowed or reduced weight gain

- Weight loss, particularly when combined with reduced calorie intake

- Prevention of weight regain following initial weight loss

- Improved bone health

- Improved physical function

- Lower risk of falls (older adults)

- Lower risk of fall-related injuries (older adults)

The Health Benefits of Physical Activity—Major Research Findings

- Regular moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the risk of many adverse health outcomes.

- Some physical activity is better than none.

- For most health outcomes, additional benefits occur as the amount of physical activity increases through higher intensity, greater frequency, and/or longer duration.

- Substantial health benefits for adults occur with 150 to 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity, such as brisk walking. Additional benefits occur with more physical activity.

- Both aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activity are beneficial.

- Health benefits occur for children and adolescents, young and middle-aged adults, older adults, and those in every studied racial and ethnic group.

- The health benefits of physical activity occur for people with chronic conditions or disabilities.

- The benefits of physical activity generally outweigh the risk of adverse outcomes or injury

Increase both Physical Activity and Physical Fitness

Increase Physical Activity: Move More, Sit Less

How much of your typical day do you spend sitting, reclining, or lying down? Are you considered a sedentary person?

Activity: Your daily movement patterns

Keep a journal and record your movement throughout the day. It is best to record a regular work day and also a weekend day.

Track the time you spend sitting, laying down, doing low intensity activities of daily living, and purposeful exercise.

Writing down a diary can help you to clearly see your active and inactive patterns in your life to help you identify opportunities for increasing physical activity.

A person who is described as sedentary means that they are sitting, reclining, or lying down. Most desk-based office work, driving a car, and watching television are examples of sedentary behaviors. It is important to limit the amount of time spent being sedentary. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity of any intensity (including light intensity) provides health benefits. If you are a sedentary person, the first thing you should do is identify opportunities throughout your day to move more and sit less.

Remember:

- Some physical activity is better than none.

- Everything counts! Move more!

Examples of strategies to increase activity throughout your day[5]:

- Walk instead of drive, whenever you can

- Walk your children to school

- Take the stairs instead of the escalator or elevator

- Take a family walk after dinner

- Replace a Sunday drive with a Sunday walk

- Go for a half-hour walk instead of watching TV

- Get off the bus a stop early, and walk

- Park farther from the store and walk

- Make a Saturday morning walk a family habit

- Walk briskly in the mall

- Take the dog on longer walks

- Go up hills instead of around them

- Garden, or make home repairs

- Do yard work. Get your children to help rake, weed, or plant

- Work around the house. Ask your children to help with active chores

- Wash the car by hand

- Use a snow shovel instead of a snow blower

- Avoid labor-saving devices, such as a remote control or electric mixers

- Do sit-ups in front of the TV. Have a sit-up competition with your kids

Some possible ways that fitness and health outcomes may relate to physical activity are:

- Physical activity leads to improvements in physical fitness, and physical fitness causes improvements in health outcomes;

- Physical fitness may modify the amount of the effect that physical activity has on health outcomes; or

- Physical activity can lead to improved physical fitness as a health outcome.

Develop an Exercise Program to Build Your Physical Fitness

At least a minimal level of physical fitness is required in order to carry out daily activities without being physically overwhelmed. To build or sustain your physical fitness it is important to develop an exercise program that targets the important components of fitness. Development of these various components will improve your quality of life, reduce your risk of chronic disease, and optimize your health and well-being.

The Components of Physical Fitness

The components of physical fitness are often categorized into health-related components and skill-related (performance-related) components. Although skill-related components are valuable, most tend to be more specific toward athletes.

- Health-related components of physical fitness: Cardiorespiratory endurance, muscle strength, muscle endurance, flexibility, and body composition.

- Skill-related components of physical fitness: Balance, agility, speed, power, coordination, and reaction time.

Descriptions of the most common components of fitness are:

- Aerobic physical activity is activity in which the body’s large muscles move in a rhythmic manner for a sustained period of time. Aerobic activity, also called endurance or cardio activity, improves cardiorespiratory fitness. Examples include brisk walking, running, swimming, and bicycling.

- Balance is a component of physical fitness that involves maintaining the body’s equilibrium while stationary or moving.

- Balance training includes static and dynamic exercises that are designed to improve individuals’ ability to resist forces within or outside of the body that cause falls while a person is stationary or moving. Walking backward, standing on one leg, or using a wobble board are examples of balance-training activities.

- Body composition is a health-related component of physical fitness that applies to body weight and the relative amounts of muscle, fat, bone, and other vital tissues of the body. Most often, the components are limited to fat and lean body mass (or fat-free mass). Bone-strengthening activity. Physical activity designed primarily to increase the strength of specific sites in bones that make up the skeletal system.

- Bone-strengthening activities produce an impact or tension force on the bones that promotes bone growth and strength. Running, jumping rope, and lifting weights are examples of bone-strengthening activities.

- Cardiorespiratory fitness (endurance) is the ability to perform large-muscle, whole-body exercise at moderate-to-vigorous intensities for extended periods of time.

- Flexibility is a health- and performance-related component of physical fitness that is the range of motion possible at a joint. Flexibility is specific to each joint and depends on a number of specific variables, including but not limited to the tightness of specific muscles and tendons. Flexibility exercises enhance the ability of a joint to move through its full range of motion.

- Muscle-strengthening activity (strength training, resistance training, or muscular strength and endurance exercises) is physical activity, including exercise, that increases skeletal muscle strength, power, endurance, and mass.

- Strength is a health and performance component of physical fitness that is the ability of a muscle or muscle group to exert force.

Drag the elements to the correct area.

General Physical Activity Recommendations for Adults

It is recommended that:

- All adults should undertake regular physical activity.

- Adults should do at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity; or at least 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity; or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week, for substantial health benefits.

- Adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities at moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days a week, as these provide additional health benefits.

- Adults may increase moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity to more than 300 minutes; or do more than 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity; or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week for additional health benefits.

Activity: Adding Physical Activity to Your Life

Don’t worry if you’re thinking, “How can I get the recommended amount of physical activity each week?” You’ll be surprised by the variety of activities you have to choose from.

Set goals, choose activities that work for you, and stay on track with the Move Your WaySM Activity Planner.

The Move Your WaySM Activity Planner is an easy to use tool that allows you to indicate the types of workouts you enjoy and provide a printable report for you to follow to ensure you are meeting the physical activity guidelines.

Principles of Training

When designing your exercise routine, remember that it is important to overload your body to allow it to respond by building more strength or increasing the capacity of your cardiorespiratory system. Since your body will adapt to the overload, you cannot continue with the same exercise routine, you need to continue to increase the demand by progressively increasing your workouts. And lastly, be sure you are including a variety of exercises intended to build each specific body system.

The three Principles of Training are:

- Overload is the physical stress placed on the body when physical activity is greater in amount or intensity than usual. The body’s structures and functions respond and adapt to these stresses. For example, aerobic physical activity places a stress on the cardiorespiratory system and muscles, requiring the lungs to move more air and the heart to pump more blood and deliver it to the working muscles. This increase in demand increases the efficiency and capacity of the lungs, heart, circulatory system, and exercising muscles. In the same way, muscle-strengthening and bone-strengthening activities overload muscles and bones, making them stronger.

- Progression is closely tied to overload. Once a person reaches a certain fitness level, he or she is able to progress to higher levels of physical activity by continued overload and adaptation. Small, progressive changes in overload help the body adapt to the additional stresses while minimizing the risk of injury.

- Specificity means that the benefits of physical activity are specific to the body systems that are doing the work. For example, the physiologic benefits of walking are largely specific to the lower body and the cardiovascular system. Push-ups primarily benefit the muscles of the chest, shoulders, and upper arms.

F.I.T.T. Principle

When designing your exercise routine, it is important to remember to target the health-related components of physical fitness and ensure you are meeting the recommended frequency, intensity, time, and type for each component, which is commonly referred to as the F.I.T.T Principle.

F.I.T.T Principle:

- Frequency refers to how often you will exercise.

- Intensity refers to how hard you will work during your exercise session.

- Time refers to how long your exercise session will be.

- Type refers to the type of exercise you will do to build your fitness.

The four elements of the F.I.T.T. principle help you create an exercise plan that will build or sustain your level of physical fitness.

F.I.T.T. for Cardiorespiratory Endurance (Aerobic Activity)

Frequency: At least 3 days a week.

Time: 150 minutes to 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 to 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity. A general rule of thumb is that 2 minutes of moderate-intensity activity counts the same as 1 minute of vigorous-intensity activity. For example, 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity is roughly the same as 15 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity. The 1996 Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health and the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans included the guidance that aerobic activity needed to last at least 10 minutes to count in your total minutes of aerobic exercise each week. However, continued research into aerobic exercise bouts has shown that moderate-vigorous aerobic exercise of any length is beneficial for your health. So remember throughout your day that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity of any duration counts toward meeting the key guidelines.

Intensity: Moderate or vigorous intensity.

Type: Any exercise where the body’s large muscles move in a rhythmic manner for a sustained period of time. Brisk walking, running, bicycling, jumping rope, and swimming are all examples. Aerobic activity causes a person’s heart to beat faster, and they will breathe harder than normal.

Measuring Cardio Intensity

The intensity of your aerobic exercise is measured by how the activity affects your heart rate and breathing. All types of aerobic activities can count as long as they are of sufficient intensity to meet the description of moderate or vigorous-intensity.

Three ways to measure aerobic intensity include:

- The Talk Test

- As a rule of thumb, a person doing moderate-intensity aerobic activity can talk, but not sing, during the activity. A person doing vigorous-intensity activity cannot say more than a few words without pausing for a breath.

- Perceived Exertion

- Using perceived exertion provides a way for a person to assess their level of effort. As a rule of thumb, on a scale of 0 to 10, where sitting is 0 and the highest level of effort possible is 10, moderate-intensity activity is a 5 or 6. Vigorous-intensity activity begins at a level of 7 or 8 out of 10.

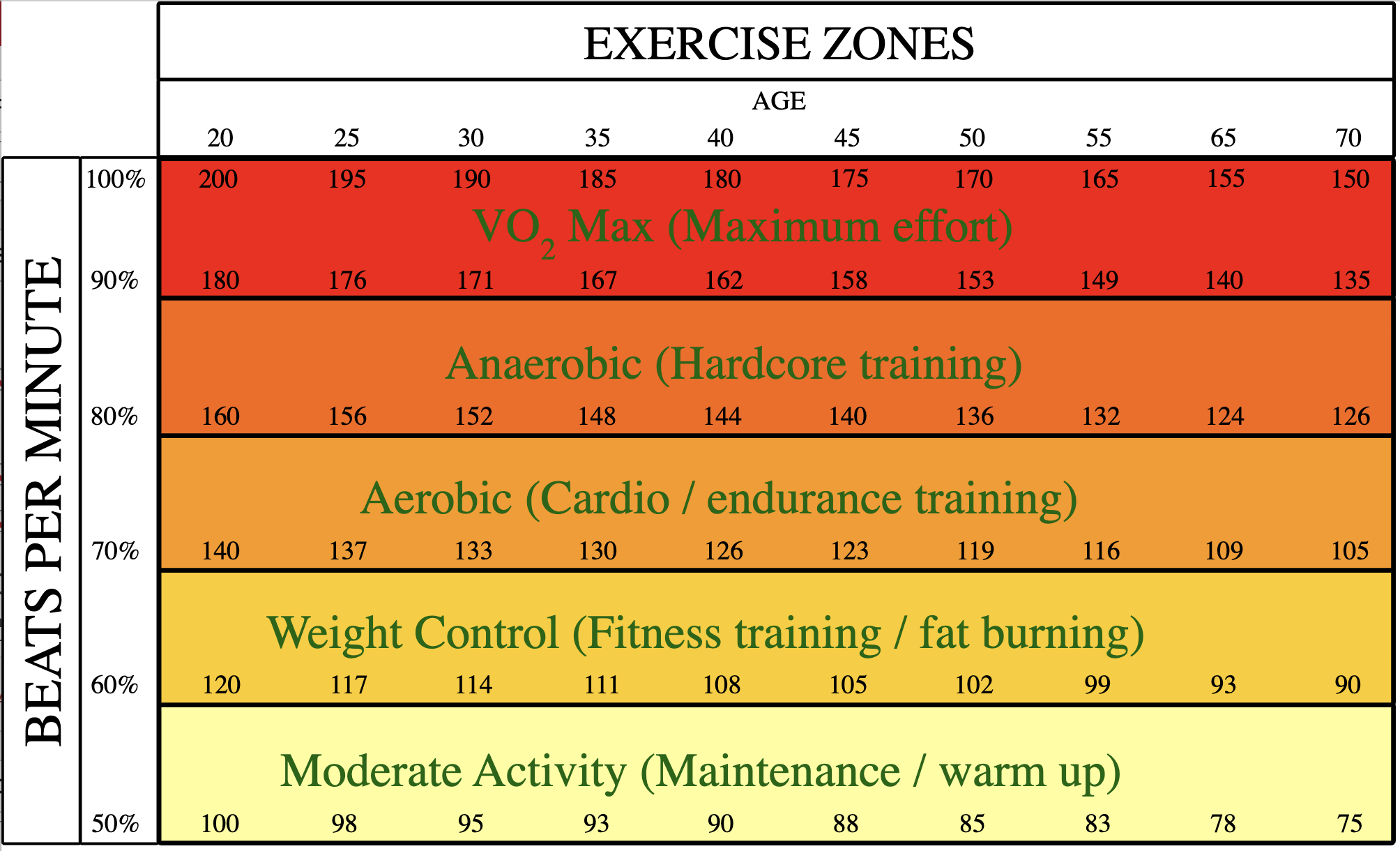

- Target Heart Rate

- Focusing on how fast your heart is beating is a good indicator of your aerobic intensity. To figure out whether you are exercising within the target heart rate zone, you must either briefly stop exercising to take your pulse or wear a heart rate monitor while exercising.

- Tips for taking your pulse:

- You can take your pulse at your neck, wrist, or chest; wrist is recommended. When taking you pulse at your wrist, place the tips of the index and middle fingers over the artery that is in line with your thumb. Do not use the thumb to take your pulse. Take a full 60-second count of the heartbeats, or take for 30 seconds and multiply by 2.

- Calculating your target heart rate

- Step 1: Calculate your maximum heart rate

- To estimate your maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220.

- 220 – [age] = [maximum heart rate]

- Example for a 25 year old

- 220- 25= 195

- To estimate your maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220.

- Step 2: Calculate what your heart rate should be for moderate and vigorous intensity

- For moderate-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 64% and 76% of your maximum heart rate.

- 64% level: [maximum heart rate] x 0.64 = [beats per minute]

- 76% level: [maximum heart rate] x 0.76 = [beats per minute]

- For example, for a 25 year old, the 64% and 76% levels would be:

- 64% level: 195 x 0.64 = 127 bpm

- 76% level: 195 x 0.76 = 148 bpm

- This shows that moderate-intensity physical activity for a 25-year-old person will require that the heart rate remains between 127 and 148 bpm during physical activity.

- For vigorous-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 77% and 93% of your maximum heart rate.

- 77% level: [maximum heart rate] x 0.77 = [beats per minute]

- 93% level: [maximum heart rate] x 0.93 = [beats per minute]

- For example, for a 25 year old, the 77% and 93% levels would be:

- 77% level: 195 x 0.77 = 150 bpm

- 93% level: 195 x 0.93 = 181 bpm

- This shows that vigorous-intensity physical activity for a 25-year-old person will require that the heart rate remains between about 150 and 181 bpm during physical activity.

- For moderate-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 64% and 76% of your maximum heart rate.

- Step 1: Calculate your maximum heart rate

F.I.T.T. for Musculoskeletal Fitness (muscle strength and endurance)

Frequency: 2 or more days a week

Time: Repetitions and Sets are typically used as the measure of the amount of time spent doing muscle strengthening exercises. A repetition is a single time you perform the exercise, and the set is a group of repetitions separated by a period of rest. A person new to strength training may see benefit doing one set of 8-12 repetitions. If a persons goal is muscular endurance they may prefer to increase their repetitions to 12-20 repetitions. If a persons goal is muscular strength they may prefer to increase the sets and reduce the repetitions, such as doing five sets of 8 repetitions.

Intensity: Muscle-strengthening exercises should be performed to the point at which it would be difficult to do another repetition. The key is to overload the muscles. If you choose to complete one set of 12 repetitions, it is important to choose a weight where the 12th repetitions is very hard.

Type: Strength exercises that target all major muscle groups. Strength exercises make muscles do more work than they are accustomed to doing, that is, they overload the muscles. Examples of muscle-strengthening activities include lifting weights, working with resistance bands, doing calisthenics that use body weight for resistance (such as push-ups, pull-ups, and planks), carrying heavy loads, and heavy gardening. Muscle-strengthening activities count if they involve a moderate or greater level of intensity or effort and work the major muscle groups of the body—the legs, hips, back, chest, abdomen, shoulders, and arms.

The three Training Principles described previously, overload, progression, and specificity, are key to muscular development. You must choose strength exercises that are challenging to overload your muscles, you must continue to increase the intensity overtime to allow your muscles to adapt and grow stronger (progression), and you need to choose exercises to ensure you are focusing on each major muscle group. Improvements in muscle strength and endurance are progressive over time. Increases in the amount of weight or the days a week of exercising will result in stronger muscles.

Avoid muscle imbalance

It is important to ensure that you are exercising all major muscle groups. When one set of muscles are stronger, weaker, or tighter than the opposing group of muscles it can cause injuries or pain, or impact your bodies alignment or posture. Muscle imbalance might occur in athletes who have one dominate side or might occur through exercising when a person only focuses on specific areas. For example, if a person only performs strength training exercises to grow their biceps, chest, and quads, they are forgetting to also train the opposing muscle groups which are the triceps, back, and hamstrings. Be sure to train the major muscles of the legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms.

F.I.T.T. for Flexibility (stretching activities)

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd edition) does not state specific recommendations for the frequency, intensity, or time for Flexibility. The following recommendations are from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)[6].

Frequency: Equal to or greater than 2-3 times per week. Daily stretching is most effective.

Time: Holding a static stretch for 10-30s is recommended for most adults. In older individuals, holding a stretch for 30-60s may confer greater benefit toward flexibility.

Intensity: Stretch to the point of feeling tightness or slight discomfort.

Type: A series of flexibility exercises for each of the major muscle-tendon units is recommended.

Challenge: Does it FITT?

There are numerous websites that provide you with workout plans or routines.

Your challenge is to find a workout routine online that is at least one week in length.

Compare the workout routine to the FITT principle. Does the routine aligns with the FITT principle? Are there any misalignment or gaps? How could the workout routine be adjusted to better align with the FITT principle?

If you are having trouble finding free online workout programs take a look at the Free workout plans from Muscle and Fitness

Guidance for your current level of physical activity

Are you inactive, insufficiently active, active, or highly active? Below is guidance specifically for your current fitness level.

Inactive means not getting any moderate- or vigorous intensity physical activity beyond basic movement from daily life activities.

- For people who are inactive, that is, people who do not do any moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity beyond basic movement from daily life activities:

- Reducing sedentary behavior has health benefits. It reduces the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality, and the incidence of type 2 diabetes and some cancers. A good first step is to replace sedentary behavior with light-intensity physical activity. Previously, evidence that light intensity physical activity could provide health benefits was not sufficient to support a recommendation.

- No matter how much time they spend in sedentary behavior or light-intensity activity, inactive people can reduce their health risks by gradually increasing their moderate-intensity physical activity.

Insufficiently active means doing some moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity but less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity or the equivalent combination. This level is less than the target range for meeting the key guidelines for adults.

- For people who are insufficiently active, that is, people who do some moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity, but who do not yet meet the key guidelines target range (150 to 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity for adults):

- Even small increases in moderate-intensity physical activity provide health benefits. There is no threshold that must be exceeded before benefits begin to occur.

- Greater benefits can be achieved by reducing sedentary behavior, increasing moderate-intensity physical activity, or a combination of both.

- For any given increase in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, the relative gain in benefits is greater for insufficiently active people than for people who are already meeting the key guidelines.

Active means doing the equivalent of 150 minutes to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week. This level meets the key guideline target range for adults.

- For people who are active, that is, people who already meet the key guidelines (150 to 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity for adults):

- Although those within the target range already have substantial benefits from their current volume of physical activity, more benefits can be gained by doing additional moderate-to-vigorous physical activity or reducing sedentary behavior.

Highly active means doing the equivalent of more than 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week. This level exceeds the key guideline target range for adults.

- For people who are highly active, that is, people who do more than the equivalent of 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity:

- These people should maintain or increase their activity level by doing a variety of activities.

Exercise Safely

Key Guidelines for Safe Physical Activity include:

- Be confident that physical activity can be safe for almost everyone, yet recognized that activities may have risks.

- Choose physical activities that are appropriate for your current fitness level.

- Increase physical activity gradually over time. Inactive people should “start low and go slow” by starting with lower intensity activities and gradually increasing how often and how long activities are done.

- Take precautions when exercising to minimize risk. This might include using appropriate gear and sports equipment, choosing safe environments, following rules and policies, and making sensible choices about when, where, and how to be active.

- If you have chronic conditions or symptoms, be sure to consult with a health care professional or physical activity specialist to discuss the types and amounts of activity appropriate for you.

Assess Your Physical Activity Readiness

To help ensure you are of good physical health to start an exercise program, you are recommended to complete the. The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone, called the PAR-Q+. This questionnaire is intended to determine if there are any underlying health issues that should be discussed with a doctor before starting an exercise program.

Take the PAR-Q+ test

Warm Up and Cool Down

Although the health benefits of including a warm-up and cool down are not yet proven, research studies of effective exercise programs typically include warm-up and cool-down activities. Warming up before and cooling down after exercise are commonly recommended to prevent injuries and adverse cardiac events. A warmup before moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity allows a gradual increase in heart rate and breathing at the start of the episode of activity. A cool-down after activity allows a gradual heart rate decrease at the end of the session.

the importance of sleep

Although Sleep is not included as an important behavior in either the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd edition) or the WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour, Sleep is addressed as an important health outcome when considering the impact of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Along with nutrition and exercise, sleep is one of the three pillars of a healthy lifestyle. Healthy sleep improves your health and quality of life in a variety of ways.

Sleep is an important part of your daily routine—you spend about one-third of your time doing it. It is estimated that about 1 in 3 adults, and even more adolescents, don’t get enough sleep, which can affect their health and well-being. People who don’t get enough sleep are more likely to have health problems like obesity, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, dementia, and cancer. They’re also more likely to have trouble at work or school. In addition, about 100,000 motor vehicle crashes every year in the United States are related to drowsy driving. It is recognized that improving sleep habits and sleep environments can help people stay healthy and safe. Thus, is is not surprising that one of the goals of Healthy People 2030 is to improve health, productivity, well-being, quality of life, and safety by helping people get enough sleep.

Getting good sleep is not just about the quantity of sleep, but also the quality of sleep. Healthy sleep requires adequate duration, good quality, appropriate timing and regularity, and the absence of sleep disturbances or disorders.

Recommended Sleep Quantity

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that adults should sleep 7 hours or more per night on a regular basis to promote optimal health.

| Age Group | Recommended Hours of Sleep Per Day |

|---|---|

| 0–3 months | 14–17 hours (National Sleep Foundation) No recommendation (American Academy of Sleep Medicine) |

| 4–12 months | 12–16 hours per 24 hours (including naps) |

| 1–2 years | 11–14 hours per 24 hours (including naps) |

| 3–5 years | 10–13 hours per 24 hours (including naps) |

| 6–12 years | 9–12 hours per 24 hours |

| 13–18 years | 8–10 hours per 24 hours |

| 18–60 years | 7 or more hours per night |

| 61–64 years | 7–9 hours |

| 65 years and older | 7–8 hours |

Healthy Sleep Habits

Tips for healthy sleep habits[8] include:

- Keep a consistent sleep schedule. Get up at the same time every day, even on weekends or during vacations.

- Set a bedtime that is early enough for you to get at least 7-8 hours of sleep.

- Don’t go to bed unless you are sleepy.

- If you don’t fall asleep after 20 minutes, get out of bed. Go do a quiet activity without a lot of light exposure. It is especially important to not get on electronics.

- Establish a relaxing bedtime routine.

- Use your bed only for sleep and sex.

- Have a warm shower/bath or a cup of herbal tea

- Make your bedroom quiet and relaxing. Keep the room at a comfortable, cool temperature.

- Do your best to avoid having disruptive pets, children, partners sleep with you

- Make sure your room is pitch black or use a sleep mask over your eyes

- Limit exposure to bright light in the evenings.

- Turn off electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bedtime.

- Don’t eat a large meal before bedtime. If you are hungry at night, eat a light, healthy snack.

- Exercise regularly and maintain a healthy diet.

- The time we spend doing moderate to vigorous activity throughout or day will benefit our sleep. Strong evidence demonstrates that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity improves the quality of sleep in adults. It does so by reducing the length of time it takes to go to sleep and reducing the time one is awake after going to sleep and before rising in the morning. It also can increase the time in deep sleep and reduce daytime sleepiness. The improvements in sleep with regular physical activity are also reported by people with insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. In children, the more they are sedentary the lower their sleep duration.

- Avoid consuming caffeine in the afternoon or evening.

- Avoid consuming alcohol before bedtime.

- Reduce your fluid intake before bedtime.

Understanding Sleep

The National Sleep Foundation provides helpful information about the basics of sleep including understanding circadian rhythms and the sleep cycle[9].

Major advances in sleep science have occurred over the past half-century since the discovery of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in 1953[10].

Circadian Rhythm

Have you heard the term circadian rhythm? Circadian means “recurring naturally on a twenty-four-hour cycle, even in the absence of light fluctuations,” it is sometimes called the “body clock.” When we talk about circadian rhythms, it’s mostly in relation to sleep.

Circadian rhythms are physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. Your circadian rhythm is regulated by your bodies biological clock, which is an organisms’ natural timing device. The master clock in the brain is a group of about 20,000 nerve cells (neurons) and coordinates all the biological clocks in a living thing, keeping the clocks in sync. Without the right signals from your body’s internal master clock, you might not fall asleep, have fragmented or sleep poorly, or wake up too early and not be able to fall back to sleep.

Your body’s biological clock produces circadian rhythms and regulates the timing of things in your body, like when you want to sleep or eat. Your circadian rhythm can influence important functions in your body such as releasing hormones, your eating habits, and your body temperature. For example, your digestive system produces proteins to make sure you eat on schedule, and the endocrine system regulates hormones to match your energy expenditures during the day.

Although natural factors in your body produce circadian rhythms, the environment, such as daylight, exercise, and temperature, also affect them. For example if you experience jet lag or change to working a night shift it could impact your light-dark cycle. The light from electronic devices at night can also confuse your biological clock and impact your circadian rhythm.

Sleep Stages (Sleep Cycle)

In 1953 there was a breakthrough in sleep science, this is when our understanding of what happens during sleep drastically changed. Prior to the 1950’s it was thought that our brains just shutdown when we slept, however in the 19050’s scientist learned that our brains do not shutdown, rather they cycle through several different stages of sleep. Dr. Nathaniel Kleitman was an American physiologist known as the Father of American sleep research, he and his students discovered what we now call REM sleep, or rapid eye movement sleep. Prior to the incredible work produced by Kleitman, it was thought that the brain and body were in a completely inactive state during sleep. It was discovered that over the course of one night, your body goes through the sleep stages every 90 minutes or so. Sleep stages last for different periods of time depending on the age of the sleeper, but generally speaking non-REM cycles are longer in the beginning of the night while REM cycles are longer later in the night.

There are two types of sleep: Non-REM and REM sleep. Non-REM sleep is furthered divided into three stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3) where distinct brain activity occurs. REM sleep involves more brain activity than Non-REM and is considered a more “wakeful” state, as your heart rate and blood pressure increase to levels close to what you experience when you are awake. While all sleep stages are important, Stage 3 and REM sleep have unique benefits. One to two hours of Stage 3 deep sleep per night will keep the average adult feeling restored and healthy. If you’re regularly waking up tired, it could be that you’re not spending enough time in that deep sleep phase. Meanwhile, REM sleep helps your brain consolidate new information and maintain your mood – both critical for daily life. Talk to your health care provider if you feel you are not getting the restful sleep that you need.

The Four Sleep Stages (cycles)

Stage 1 (Non-REM)

Stage 1 of the sleep cycle is the lightest phase of sleep and generally lasts about seven minutes. The sleeper is somewhat alert and can be woken up easily. During this stage, the heartbeat and breathing slow down while muscles begin to relax. The brain produces alpha and theta waves.

Stage 2 (Non-REM)

In Stage 2, the brain creates brief bursts of electrical activity known as “sleep spindles” that create a distinct sawtooth pattern on recordings of brain activity. Eventually, the waves continue to slow down. Stage 2 is still considered a light phase of sleep, but the sleeper is less likely to be awakened. Heart rate and breathing slow down even more, and the body temperature drops. This stage lasts around 25 minutes.

Stage 3 (Non-REM)

This stage represents the body falling into a deep sleep, where slow wave sleep occurs. The brain produces slower delta waves, and there’s no eye movement or muscle activity from the sleeper. As the brain produces even more delta waves, the sleeper enters an important restorative sleep stage from which it’s difficult to be awakened. This phase of deep sleep is what helps you feel refreshed in the morning. It’s also the phase in which your body repairs muscle and tissue, encourages growth and development, and improves immune function.

Stage 4 – REM Sleep

About 90 minutes after falling asleep, your body enters REM sleep, which stands for Rapid Eye Movement sleep and is named so for the way your eyes quickly move back and forth behind your eyelids. REM sleep is thought to play a role in central nervous system development in infants, which might explain why infants need more REM sleep than adults. This sleep pattern is characterized by dreaming, since your brain is very active during this stage. Physically, your body experiences faster and irregular breathing, increased heart rate, and increased blood pressure; however, your arm and leg muscles become temporarily paralyzed, stopping you from acting out your dreams. REM sleep increases with each new sleep cycle, starting at about ten minutes during the first cycle and lasting up to an hour in the final cycle. Stage 4 is the last stage before the cycle repeats. REM sleep is critical for learning, memory, daytime concentration, and your mood. REM sleep plays a significant role in helping your brain consolidate and process new information and then retain the information in your long-term memory. Without REM sleep, your immune system could be weakened, you may experience pain more deeply, poor memory, mood dysfunction, less ability to focus, and the growth of new healthy cells and tissue in the body might be blocked. Poor REM sleep may be due to sleep disorders such as insomnia or obstructive sleep apnea, which causes you to wake during the night.

Sleep Disorders

Quality of sleep is impacted by several types of sleep disorders[11] including insomnia, hypersomnias (or excessive sleep), circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, parasomnias (or sleep events), sleep-related breathing disorders, or sleep-related movement disorders. Sleep disorders, like sleep apnea, negatively affect people’s health and safety, and many adults who have a sleep disorder don’t get the treatment they need.

Raising awareness about sleep disorders can help people recognize symptoms and get the help they need. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) provides extensive information and resources about sleep disorders to help inform you about the different types, symptoms, and treatments.

Challenge: Understand Your Sleep

A sleep diary is a useful way to track your sleep at home by recording when you went to bed, woke during the night, and woke in the morning. It is helpful to also track the time of day when you exercise, nap, or take a medication, and when you have caffeine or alcohol.

A sleep diary will help you understand your sleep pattern and how much sleep you’re getting. It also will show how often you have disrupted sleep. It may also will help you note certain activities that can affect your sleep.

Keeping a sleep diary is very helpful for communicating with your doctor about your sleep.

Use the AASM Sleep Diary

Key Takeaways for Chapter 2

- It is important to be physical fit to be able to enjoy life.

- Being active everyday and purposefully exercising are important for your physical fitness.

- It is generally accepted that physical activity and exercise are beneficial for everyone, however it is important to communicate with your doctor.

- You need to do cardiorespiratory endurance exercise to support and build your heart and lungs.

- Cardio exercise intensity should be moderate to vigorous which can be measured by your perceived intensity or by measuring your heart rate.

- Cardio in any length is beneficial with a goal of a cumulative total of 150-300 minutes total from at least three days.

- Cardio exercises include any exercises where the body’s large muscles move in a rhythmic manner for a sustained period of time.

- You need to do strength training exercises to maintain and build your skeletal muscle.

- You must challenge your muscles by overloading them. You can do this by increasing the weight used or increasing the repetitions and sets.

- Make sure to strength train all major muscles groups at least two days/week.

- Stretching is important for flexibility.

- Getting adequate sleep is important for your health.

Media Attributions

- Exercise zones Fox and Haskell © Morgoth666 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Retrieved from https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf#page=32 ↵

- WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 ↵

- Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/initiatives/gappa ↵

- Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 100(2), 126–131. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1424733/ ↵

- Tips to Help You Exercise More, Get Active, NHLBI, NIH. (2013, February 13). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/get-active/getting-active.htm ↵

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2021, March 18). Stretching and Flexibility Guidelines Update. ACSM. https://www.acsm.org/all-blog-posts/certification-blog/acsm-certified-blog/2021/03/18/stretching-and-flexibility-guidelines-update ↵

- CDC - How Much Sleep Do I Need? - Sleep and Sleep Disorders. (2017, March 2). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/how_much_sleep.html ↵

- Troy, D. (2021, April 2). Healthy Sleep Habits. Sleep Education. https://sleepeducation.org/healthy-sleep/healthy-sleep-habits/ ↵

- Sleep Health Topics. (2021, June 18). National Sleep Foundation. https://www.thensf.org/sleep-health-topics/ ↵

- Shepard, J. W., Jr, Buysse, D. J., Chesson, A. L., Jr, Dement, W. C., Goldberg, R., Guilleminault, C., Harris, C. D., Iber, C., Mignot, E., Mitler, M. M., Moore, K. E., Phillips, B. A., Quan, S. F., Rosenberg, R. S., Roth, T., Schmidt, H. S., Silber, M. H., Walsh, J. K., & White, D. P. (2005). History of the development of sleep medicine in the United States. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 1(1), 61–82. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2413168/ ↵

- Sleep Education by AASM. (2021, December 3). Learn about Sleep Disorders. Sleep Education. https://sleepeducation.org/sleep-disorders/ ↵