The United Nations system has the invaluable ability to employ, under a unified leadership, a mix of civilian, military and police capabilities in support of a fragile peace process. Integrated missions are designed to facilitate a coherent system-wide approach to assisting countries experiencing or emerging from conflict on their path to peace and post-conflict recovery. The UN Policy on Integrated Assessment and Planning (IAP) states that the UN system should be configured in an Integrated Mission or an Integrated Approach in all conflict and post- conflict situations in which a UNCT, a multidimensional peacekeeping operation or a Special Political Mission/Office is present.[1] A UN peace operation becomes an Integrated Mission when Resident Coordinator/Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) functions are part of the peacekeeping mission. Its presence is underpinned by a shared vision of the UN’s strategic objectives that reflects a common understanding of the operating environment as well as agreement on how to maximize and measure the effectiveness, efficiency and impact of the overall UN response.

In complex environments, the MLT should meet regularly in order to agree on overarching aims, build trust, and enhance teamwork. Furthermore, the team must develop a shared understanding of the political strategy and a “theory of change” on how to achieve the expected mission objectives and implement the mandate.

Experience has shown that integration and trust develop more easily between the leaders and staffs of the various components when key elements of a mission are co-located. If component headquarters are dispersed and contact between members of the MLT is reduced, this can undermine the mission’s effectiveness, security and level of cooperation. In addition to the maintenance of open lines of communication, the MLT can improve its shared understanding and effectiveness through the establishment of a number of integrated structures, such as a Joint Operations Centre (JOC), a Joint Mission Analysis Centre (JMAC) and a Mission Support Centre. Overall, the structure of the mission should be determined by functionality rather than bureaucratic considerations. Expertise should be placed where it is most needed to improve integration and communication, which may not necessarily be within its parent component.

These two principles – a shared idea of how to implement the mission plan, and the importance of co-location – apply equally at the regional or sector levels, where it is desirable for the Civilian, Military and Police components to be co-located wherever possible and appropriate. Humanitarian agencies often prefer to be located in separate facilities based on the humanitarian principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence. In addition, UN police may need to position themselves adjacent to host-state police facilities.

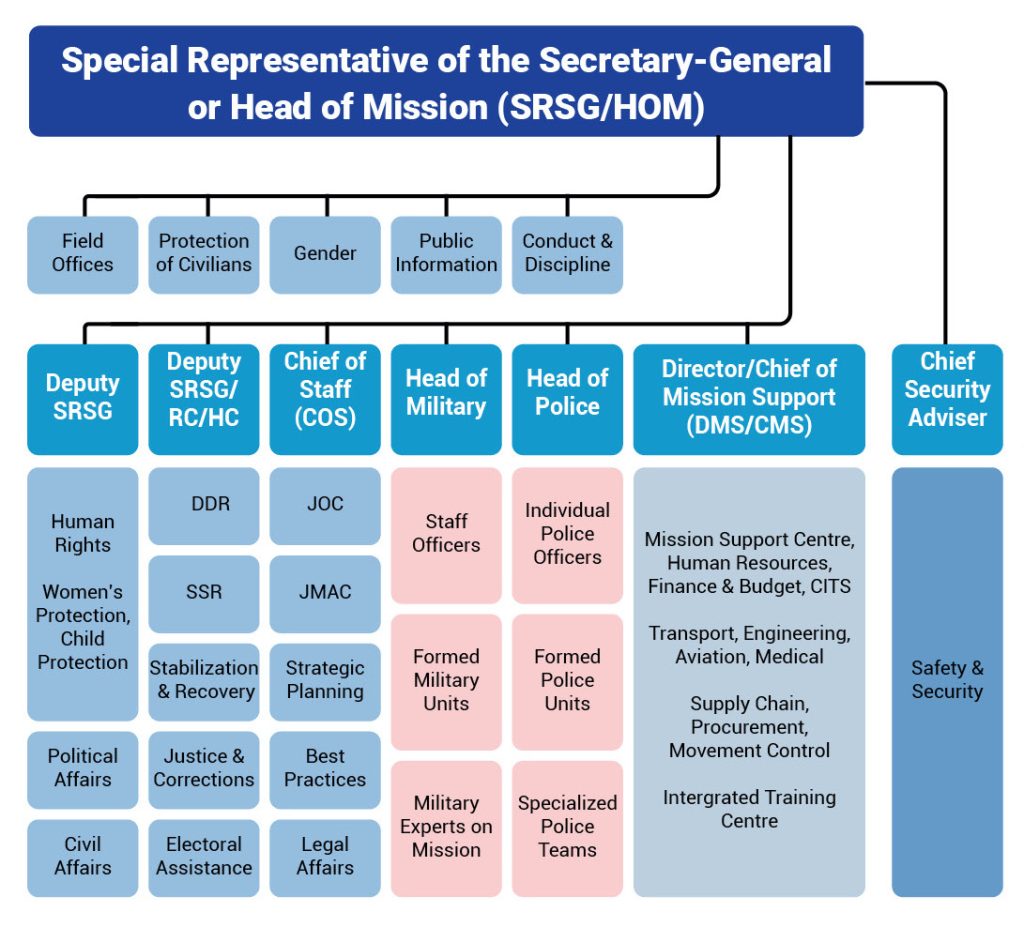

A schematic model of an integrated UN mission is shown in Figure 2.1. It should be noted that the model is purely illustrative, since the actual structure will vary from one mission to another depending on their mandates, the resources available, the allocation of functional responsibilities to senior leaders, and the conditions on the ground. The model also illustrates the linkages between mission components, and between the mission and the wider UN system through the coordinating position of the Deputy Special Representative of the Secretary-General–Resident Coordinator/Humanitarian Coordinator (DSRSG-RC/HC).

Figure 2.1 Generic United Nations integrated mission structure

All members of the MLT need to understand the roles and responsibilities of the various UN agencies, funds and programmes present in the country, and of the overarching IAP framework. The MLT should take the lead in promoting the best possible working relations between all the UN entities operating in the same country or conflict zone. This task is often the responsibility of the DSRSG-RC/HC, who has overall responsibility for coordination within the UN family. The HoM, together with the DSRSG-RC/HC, will need to strike a delicate balance between creating a secure and stable environment through the work of the mission and its military forces and police services, and preserving and respecting the “humanitarian space” for UN agencies and their partners on the ground. Given aligned overall objectives and continuous communication, these should not be regarded as conflicting priorities, but rather as a polarity that should be managed. Nonetheless, ensuring effective civil–military cooperation and coordination among elements of the wider UN and with international partners is one of the most difficult challenges that the MLT will face.

In addition to ensuring intra-UN integration, a mission will also need to ensure that there is an adequate level of targeted coordination with a wide range of relevant international, regional and host-country actors. This will require the MLT to maintain a high degree of sensitivity towards the respective mandates, interests and operating cultures of such actors. Results-oriented partnerships are the key to success, and the level of mutual interdependence will be high.

Integrated UN missions are often deployed alongside a variety of international, regional and UN Member State actors with their own mandates, agendas and time horizons. Developing fruitful and dynamic partnerships with all the relevant international presences is of the utmost importance; alignment of overall efforts is a strategic imperative.

- UN DPO/DOS, ‘Interim Policy on Integrated Assessment and Planning’, 2018. ↵