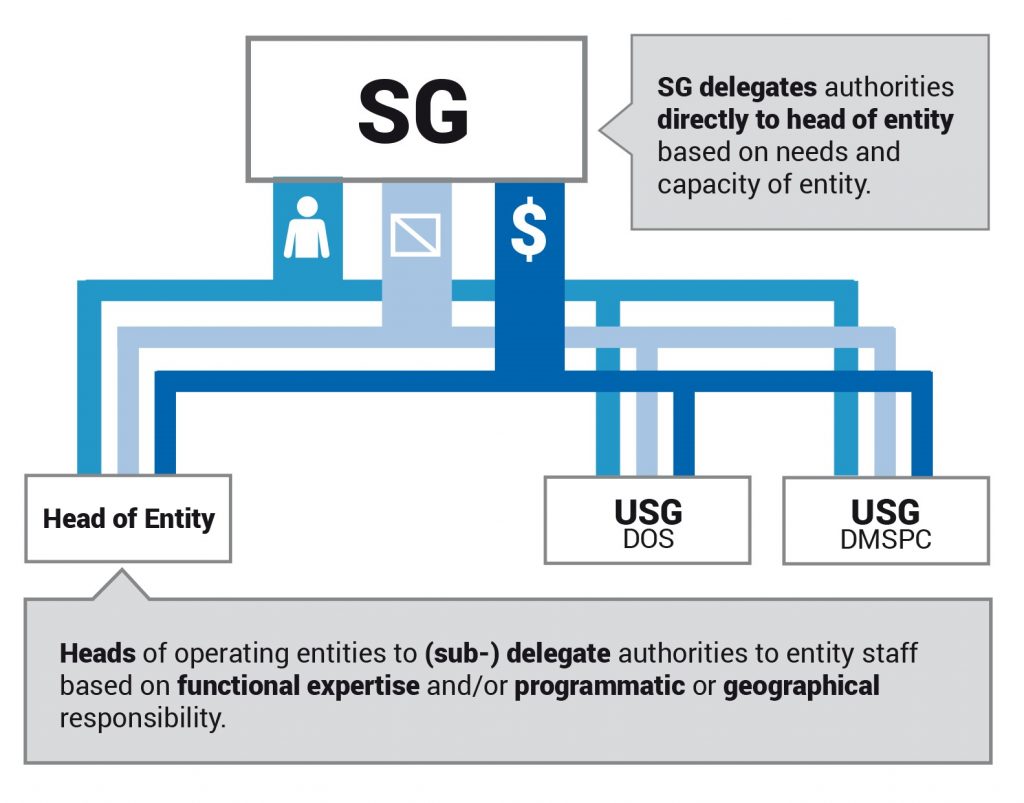

As part of the UN Secretary-General’s management reforms, the HoM has been granted greater delegation of authority (DoA). In principle, more authorities will be delegated directly from the Secretary-General to the “Head of Entity” which, in a peacekeeping operation, means the HoM/SRSG. These authorities include human resources, finance and budget, procurement, and property management (see Figure 2.4). Some can be delegated further but the HoM still retains overall authority and accountability. The HoM will clearly be advised on their delegations and the implications of these delegations, but the new system of DoA, and the accountability that goes with it, is designed to put a stronger and more transparent focus on the field and measurable results. It will have a significant impact on the business of the HoM/SRSG and the MLT.

Key UN Policies & Guidance

For more on the UN’s management reforms see https://reform.un.org.

The MLT must assess all of its proposals and plans against the human and financial resources available from the UN peacekeeping budget and other sources. While peacekeeping operations are funded through assessed contributions, programmatic aspects of the mandate, such as DDR or elections, largely depend on voluntary funding, which often falls short of the pledges made. It might be useful for the MLT to seek technical advice from World Bank representatives in priority areas where it has a clear comparative advantage.

Figure 2.4 Revised delegation of authority framework

The MLT should oversee the preparation of the mission’s budget to support successful mandate implementation. While now being given direct DoA from the Secretary General, the HoM/SRSG should understand that the mission will still have to follow the financial rules and regulations laid down by the UN General Assembly. The Director of Mission Support remains the key advisor to the MLT in this regard.

Budgetary considerations need to be factored in when deciding the goals, objectives, and particularly the priorities and sequencing of competing mission activities. Plans need to consider both the assessed budget and other funds and donors that can contribute to mandate implementation.

The MLT needs to be aware that unless budgetary resources are built into the planning process and a cooperative understanding is developed for their resolution, such issues can become a major source of friction within a mission. Within the MLT, close working relations based on good coordination, cooperation, consensus and effective communication go a long way towards improving integration and ameliorating competition for limited resources.

Staffing

The most important resource of a mission is its personnel. Qualified, competent and dedicated personnel at all levels can make or break a mission. While the recruitment of the leadership is the responsibility of UNHQ, the MLT and in particular the HoM has authority and respon- sibility for the recruitment of mission staff with the required skills and integrity. Managers should ensure that vacancies are filled in a timely manner, and that staff receive the necessary training and opportunities for advancement. Maintaining high morale within the mission is also an important factor in retaining competent staff members.

Ensuring gender parity within the mission contributes to the overall effectiveness of peace operations. Ambitious targets for gender parity in missions have been set by the Secretary-General. Women in peacekeeping give missions greater scope to engage in community outreach, support more effective mandate implementation and ‘decrease incidents of sexual exploitation and abuse’.[1] Increasing women’s participation requires a willingness within the senior leadership not only to bolster the number of women serving in key positions, but also to ensure female interlocutors in all stages of the peace process.

MINUJUSTH: Delegation of authority

Integrated missions are designed to facilitate a coherent system-wide approach to assisting countries in – or emerging from – conflict on their path to peace and post-conflict recovery. However, the financial rules and regulations that govern the use of assessed resources sometimes appear to be in conflict with achieving the desired level of integration.

Leadership, creativity and innovation are needed to effectively achieve mandates within the regulatory framework.

The UN Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH) completed its peacekeeping mandate in October 2019. The UN Security Council mandated a follow-on special political mission, the UN Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH), to “work in an advisory capacity with Haitian authorities and the UN Country Team (UNCT) to further the consolidation of the stability, security, governance, rule of law, and human rights gains achieved since 2004”. The Security Council noted that the UNCT would assume MINUJUSTH programmatic and technical assistance roles and encouraged MINUJUSTH to collaborate with the UNCT for a seamless transition.

To achieve the UNCT mandate, the World Food Programme (WFP) as lead agency in Haiti proposed establishing a “One UN” facility and requested MINUJUSTH to gift several million dollars of assets and materials to WFP in Haiti.

According to the UN’s financial rules, MINUJUSTH could sell its assets to WFP at a “nominal price” if it determined that the “interests of the United Nations will be served” and if the equipment was “not required for current or future peacekeeping operations or other United Nations activities funded from assessed contributions”.

Since it was unclear that gifting the specific equipment requested would serve the interests of the UN, the ensuing discussion focused on balancing the seemingly conflicting principles of complying with the Financial Rules and facilitating UN integration in Haiti. The wrong decision could either deprive UN Member States of their appropriate financial credit or reduce the collective resources available for furthering overall UN objectives in Haiti.

The Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General (SRSG) had delegated authorities for the disposal of UN property while complying with UN Financial Rules and Regulations. After considerable discussions between and among the WFP team in Haiti, MINUJUSTH, the UN Department of Operational Support, and WFP headquarters, a service-level agreement was negotiated for WFP to provide certain services to BINUH on a cost-recovery basis. It was agreed that this arrangement provided significant benefits to the UN and thus justified the gifting or sale at nominal cost of a subset of equipment originally requested by WFP.

This seemingly mundane administrative question became the catalyst for a broader discussion about responsibilities related to delegation of authorities and backstopping by UN Headquarters. It was important for the entire Mission Leadership Team to engage in discussions regarding the contrast between the mission’s obligation to recoup as much of the assessed funding provided by Member States as possible with the operational imperatives of meaningful integration. The MINUJUSTH SRSG, the Deputy SRSG (Resident Coordinator/ Humanitarian Coordinator), the Chief of Mission Support, the Chief of Staff and the Police Commissioner were all engaged in these discussions, and in lively discussions with their respective counterparts in UNHQ and the UNCT.

Stephen Liebermen, former Special Adviser to the SRSG, MINUJUSTH, 2019

- UN General Assembly, ‘Report of the Secretary-General, Implementation of the recommendations of the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations’, 3 November 2017, p. 22. ↵