2 Trade: International Institutions

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the functions of trade as a building block for International Political Economy.

- Gain greater insight into the functions of GATT and WTO in reference to the International Political Economy.

- Recognize the importance of institutional design facilitating policy goals, especially internationally.

- Utilize critical thinking to determine the significance of WTO and its efforts today on the international stage.

Introduction

Immediately after the conclusion of World War II, the United States emerged as a dominant leader in the world. The postwar period involved a great global push towards trade liberalization, with the United States leading the way. With the intention of becoming the main global super-power, “After World War II, US policymakers used trade policy to cement a connection between trade liberalization and economic/political stability.” (Aaronson 2001, p. 31). Along with much of the Western World, The US trade connections to create a strong economic opposition against the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. Thus, many countries with Marxist/Communist inspired economies did not fully participate in the global expansion of trade, which has led some to argue that the driving force behind the postwar growth of trade was fear of enemy gains from trade (Gowa XXXX). Still, in the following years, international trade would flourish in economically and politically allied countries with the United States at the helm, highlighting the concepts of the hegemonic stability theory (HST), mentioned in Chapter 1. Meanwhile, increased globalization and economic interactions between countries made it clear that a set of international rules and guidelines for trade had to be implemented. Many nations believed in the benefits of creating and joining an international institution responsible for trade, such as “enforceable reciprocal commitments” and allowing leaders of states to reduce domestic pressures for trade protection (Davis and Pelc 2015).

The postwar expansion of international trade can be divided into three explanations, an international leadership approach (through HST), a Cold War alliance approach, and an international institutions approach. Commonly, the international institutions’ explanation of trade is used in recent times when referencing the expansions of trade in the 20th century, but to some degree all of these factors played an important role in the global expansion of trade.

With these international institutions in mind, the post-World War II landscape in Europe was politically and economically devastated. Having already suffered the economic ills of the Great Depression, Europe’s economy was in shambles by the end of the war. As a result, this led to the Bretton Woods Conference (1944), an attempt to create an international institution looking to revitalize Europe’s economies and set the standards for international trade. Although the original plans of the Bretton Woods Conference regarding trade did not come to fruition, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) would serve as the guidelines for international trade. Arising as a set of temporary guidelines, GATT would go on to become the official foundation for trade in the following years to come. Beginning with only 23 members, GATT would expand, adding more member countries and finding new challenges as time passed on. Numerous rounds of negotiations occurred to clarify rules and to make GATT adaptable to an ever-changing global economic environment. Ultimately, the Uruguay Round (1986-93) resulted in the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the current overseer of international trade. The WTO has tried to further set the rules of global trade, while it also implemented new rules to ensure smooth processes of trade in the world. Notably, the Doha Round (2002-2015) was another attempt to revitalize the rules and international trading system, but it was not met with resounding success, and in general, the WTO’s ability to increase international trade is now widely questioned.

The rest of the following chapter is dedicated to taking a closer look at the Bretton Woods conference, GATT, the Uruguay Round, the WTO, and the Doha Round. Additionally, it must be noted that the WTO’s current position in relation to international trade should be analyzed, especially in how it has declined in significance.

International Trade Organization (ITO)

In 1944, with World War II ending, the allied nations were expecting to achieve victory. It wasn’t long until they realized that much had to be done to restore national economies and to facilitate international trade. Even without taking the Great Depression into account, the devastation of World War II lowered the standard of living by at least 25 years in victorious states while losing countries experienced significantly worse. To restore international economic stability, 44 allied states or governments met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. This meeting is most notoriously known as the “Bretton Woods Conference”, called for the creation of three separate distinct institutions: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the International Trade Organization (ITO). The purpose of the IBRD was “to create a credit system that would allow states desperate in the need of foreign aid to receive long-term capital investments. The goal of the IMF was “to secure international monetary cooperation, to stabilize currency exchange rates, and to expand international liquidity in order to access hard currencies” (Mcquillan 2023 XXXX). Finally, the ITO would be responsible for reducing trade tariffs and incentivizing economic cooperation among the world’s states.

Although the IMF and the IBRD were established in 1945 and 1946 respectively, the ITO was delayed mainly due to domestic concerns in the United States, which received disproportionate voting power in the other two Bretton Woods institutions. The US Congress was displeased with the idea of having just one vote in the ITO, and so, consequently, the organization was never brought to a vote. Without American support, the ITO never came into existence. What was meant to be temporary sets of treaties arose to dictate international trade: the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

In 1947, 23 countries agreed to arrange central principles and constraints on trade policies nationally via the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The goal of GATT was to increase international trade, eliminate harmful trade protectionism, reduce any likelihood of war, and improve communications with all member countries. Initial negotiations were held at the Palais de Nations in Geneva and resulted in a set of rules for agreeing to reductions in trade restrictions.

GATT was not designed to be the centerpiece of postwar trade liberalization. It was not as inclusive as the originally planned ITO, which involved over 50 countries. GATT had no organizational structure and expected to depend on the ITO for institutional support. Furthermore, GATT contained grandfather rights exemptions, which allowed its signatories to retain pre-existing forms of trade legislation that would bypass GATT rules. The ambiguous aspect of GATT’s guidelines meant that the decisions of what member countries could and could not do was not quite unclear. Because GATT’s existence had no clear legal basis or foundation, GATT’s dispute settlement process contained defects, the biggest of which was that any one member could block the findings of any dispute rulings. In effect, GATT allowed each member to prevent negative findings against it.

Nevertheless, modifications and adaptations to GATT would result in many positive changes to the organization. These negotiations helped to ignite a more global response to trade and shifted the organization towards a more rules-oriented trade regime with less protection. The following table lists the rounds of negotiations that occurred during the GATT period.

Most early negotiations concentrated on tariffs, taxes on imports that were the primary method of insulating economies from international trade. Countries would negotiate a ceiling, called a bound tariff, that set the limit over which tariffs were not allowed to rise. As time went on, GATT negotiations moved toward eliminating tariffs to promote more free trade. Such negotiating eventually led to more success for member states’ economies (see Chapter XX). Slowly, but surely, more and more member states began to join GATT, as they became convinced of the benefits of international trade. As negotiations succeeded on tariffs, members eventually turned towards other, more complex trade barriers, such as antidumping duties, that became primary methods of trade protection as the use of tariffs waned. By 1993, 128 countries grew to be a part of GATT. Once again economic issues, global trends, and GATT’s increasing size would lead to another round of trade negotiations.

The Uruguay Round

Lasting from 1986 to 1993, the Uruguay Round of negotiations had two specific objectives; to bring overlooked areas of commerce to the GATT system and incorporate areas like agricultural sectors that had previously been ignored by the trade liberalization agenda. The Uruguay Round incorporated many aspects of the trade policy, including services and intellectual property, that were not previously part of the GATT regime (Barton, et al., 2008 p.93). It was one of the most successful rounds by making agreements more applicable to all parties by implementing all elements of the state.

Import Licensing Agreements are used for reducing abusive behavior, and trade distortions, and aim to simplify and bring transparency to import licensing procedures (Mavroidis, 2016). The first Import Licensing Agreement (ILA) was concluded and enforced by January 1980 under the Tokyo round negotiations and then was further expanded in the Uruguay Round agreements (Mavroidis, 2016). This is most significant in the case of Uruguay Round negotiations, where other trading nations kept the same agreements as the Tokyo round negotiations about ILAs.

During the Uruguay Round, trading nations negotiated to make sure licensing procedures do not affect international trade, unlike previous negotiations. The Uruguay round failed to define import licensing even though definitions were proposed due to nations being unable to come up with an agreed-upon definition. Article XI of GATT was inconsistent stating that unless an import license is automatic, it does not establish exactly the requirements of automaticity. Article XIII included the transparency requirement that was, according to Article VIII of GATT, subject to disciplinary action. However, there was no case law in reference to disciplinary action ever being brought up due to a lack of transparency. Article XXV of GATT failed to provide details of how licenses are obtained, leaving member countries to either create their own rules or guess as to what GATT would like. Due to GATT being unclear on import licensing, trading nations followed the ILA’s’ provisions on import license approval. Which made clear that there were requirements that were established and that the “freely granted clause” did not guarantee an import license approval.

Another pre-GATT trade agreement was the pre-shipment inspection (PSI), which is quality assurance for traders. PSI ensures that the trade conforms to the sales contract as stated in Article 1.3 of the agreement. The United States was not on board with the PSIs, so the European Union and the United States began to adjudicate disputes. In the Uruguay Round, to keep traders from distorting imports and to keep states from restricting trade, this clarification on PSIs was negotiated and agreed upon. The logic of the WTO is to try and control the behavior of authorities at customs by being strict with the customs procedures and dissuading traders, in comparison GATT was ambiguously vague. The GATT era Tokyo round gathered the nations, while the Uruguay Round introduced the Agreement Trade Facilitation ATF agreement. The WTO reported industrialized countries have reduced their tariffs on industrial products by 36 percent during the first five GATT rounds (1942-1962).

The Tokyo round negotiations planned to control the evaluation systems by starting a uniform customs evaluation, however, the agreement was superseded by the Uruguay round Customs Valuation Agreement (CVA). Ministers came together and accepted the agenda because they felt it did not leave anything out in terms of trade policy issues. It is evident that collective action for smaller groups like firms and farmers can influence policy. The countries also can be negatively affected by collective action per prisoner’s dilemma theory where every country has self-interest and avoids the race to the bottom.

Even if the Uruguay Round may have had some faults, it was still clearly the most important step taken to further trade liberalization since the 1940s. As a result, more tariffs were lowered in the world, and more nations became official members of the GATT organization. The Uruguay Development Round (or The Uruguay Round) was perhaps one of the largest sets of trade negotiations introduced in modern history and took “seven and a half years,” lasting from 1986 to 1993. (WTO n.d.). It was not only the most encompassing in terms of the issues it targeted (the round focused on issues like “services liberalization…intellectual property rights, and sanitary and phytosanitary standards…”), but was directly responsible for the creation of the WTO in 1995.

The World Trade Organization

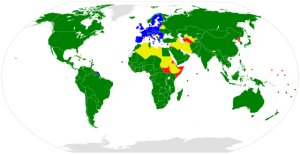

The World Trade Organization is a young organization that only came into existence after succeeding GATT in 1995 during the Uruguay rounds. WTO is a global organization that focuses on trade between nations in its membership. The goal of the WTO is to ensure that global trade happens “smoothly, freely, and predictably” (Heakal 2022). The WTO currently has 163 members, all of which have ratified the rules of the organization in their individual countries. The WTO tends to support the removal of free trade barriers, which allows international trade to follow its natural course without hindrances such as tariffs, quotas, or other restrictions.

The WTO has six objectives: (1) to create and enforce rules for international trade, (2) to provide a forum for negotiating and monitoring trade liberalization, (3) to create a space to resolve trade disputes, (4) to increase the transparency of countries decision-making process, (5) to cooperate with other major international economic institutes that are involved in economic management globally, and (6) to aid developing countries so they may benefit fully from the global trade system (Anderson 2021). By encompassing all goods, services, intellectual property, and investment property, the WTO pursues its objectives more comprehensively than GATT- which focuses exclusively on goods. Through these objections, the WTO attempts to ensure stability in global trade.

The WTO prevents countries from discriminating between their trading partners through principles such as the Most Favored Nation treatment and National Treatment. The Most Favored Nation treatment requires countries to provide identical treatment to all other members of the WTO. For example, if the United States were to apply a 2.6 percent tariff on an import from the European Union, then the United States must apply a roughly 2.5 percent tariff on imports from every other WTO member country. The WTO does allow for some exceptions, such as member countries being allowed to set up free trade agreements with other members. Developing countries can gain special access to markets, and countries can choose to raise barriers against products, and in some instances services, that are unfairly traded from specific countries (WTO 2022). This means that nations may have their Most Favored Nations Status removed. Currently, the United States has suspended 30 total countries from their Most Favored Nation status (Kenton 2021). For example, as of April 7, 2022, the United States Congress voted to strip Russia of its Most Favored Nation Status following the invasion of Ukraine.

The WTO uses national treatment as another nondiscrimination policy. The national treatment requires WTO members to treat foreign products no differently than the domestic product after the product has cleared customs. Under national treatment, countries may still apply tariffs to foreign products that would otherwise not be applied to the domestic product with the caveat that the foreign product must be treated equally after it passes through customs (Saylor Academy 2022) For example, should a country put a tax on children’s toys, the country would be required to apply that tax equally between foreign and domestic children’s toys.

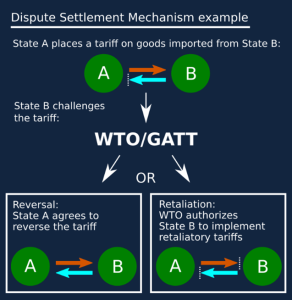

Dispute Settlement Mechanism

Disputes may arise in the WTO if a member country adopts a trade policy or takes an action that a fellow-WTO member believes to be breaking a WTO rule or obligation. The Dispute Settlement Mechanism was introduced during the Uruguay Round agreement after GATT dispute settlement measures lacked fixed timetables which created a court backlog. The Uruguay Round introduced a structured process with clearly defined stages, and greater consideration for the length of time the case should take (WTO 2022). For example, should a case run its full course, with an appeal, the case should only take 15 months. It is important to note that these cases do frequently go on longer than is statutorily allowed.

The WTO dispute settlement process begins with a request for informal consultation between parties. Should the consultation fail to resolve the dispute, the party may request the appointment of an investigative panel, which comprises three members. After receiving oral and written submissions from both parties, the panel issues a report along with the panel’s recommendations. Should a party wish, they may seek an appellate review of the panel’s report and recommendations. The appellate body may uphold, modify, or reverse the panel’s report and recommendations (Georgetown Guides 2021). However, most cases do not reach the panel phase of the dispute settlement.

The Doha Round

Despite the Uruguay Round’s successes, it left several problems unresolved. Despite all that was achieved by the Uruguay Round, these trade negotiations ultimately failed to do one thing: provide a fair distribution of real/tangible benefits for developing countries. The Uruguay Round failed to offer “greater access to the markets of developed countries for [developing countries’] products” and any assistance that was offered to these developing countries was meant to “enable the developing countries to comply with those WTO agreements…designed to enhance the interests of the developed countries…” (Subedi pg. 427). It was this failure of the Uruguay Round, among several others, that served as the impetus for the WTO, during its 4th Ministerial Conference in Doha, Qatar in November 2001, to officially establish the new Doha Development Round (or The Doha Round). The Doha Round was meant to address some of the shortcomings of the previous Uruguay Round, which included the needs of developing/less-developed WTO member countries. In this regard, the agenda for the Doha Round seemed straightforward. Though many items and issues were discussed, there were three central issues around which the Doha Round centered: 1.) Reduced tariffs on exports of developing countries; 2.) Facilitating freer trade for agriculture/agricultural goods; and 3.) Revising rules surrounding trade in services. Unfortunately, the Doha Round didn’t achieve anything substantial, let alone what it initially set out to do. Negotiations, which lasted for 14 years after the start of the 4th ministerial conference in 2001, were riddled with “persistent differences among the United States, the European Union (EU), and developing countries on major issues” and how these issues should be settled (Cimino-Isaacs & Fefer 2022).

However, unlike the Uruguay Round, the Doha Round was never able to achieve the same number of successes. The Doha Round ultimately failed to achieve many of the issues on its initial agenda during its odd 14-year period. One of the biggest issues that wasn’t properly addressed in the previous Uruguay Round was agriculture and agricultural trade/tariffs for developing nations. The subject of agricultural tariff reduction and more open access for developing countries in the realm of agricultural trade was an incredibly touchy subject regarding international trade. Historically, agriculture is one area of international trade that the most developed countries are extremely protective of, much to the detriment of developing countries. Producers in developed countries are protected by high tariffs and domestic government subsidies which, among other measures, have effectively barred developing countries from achieving any meaningful economic growth/trade liberalization on this front. So, the Doha Round’s objectives became apparent: to fully get rid of “all forms of export subsidies, and substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic support,” (Verbiest et al. 2002, pg. 4). On this front, the Doha Round managed to achieve a few things, but ultimately fell short of completely and satisfactorily addressing the major grievances that developing countries had with agricultural trade. Fortunately, the Doha Round did make some headway in this area but, as we’ll soon discuss, there is some disagreement over the purported effectiveness of some of the solutions proposed in this round. Firstly, the participating member countries of the Doha Round all officially agreed to eventually abolish export subsidies “by 2013”, a decision “secured in the Hong Kong Ministerial in 2005,” (WTO n.d.; Laborde & Martin 2012, pg. 273). Despite this consensus however, this agreement’s “effectiveness might be somewhat less than suggested,” given that export subsidies can essentially be “replaced by the same subsidy provided as a domestic subsidy,” (Lester 2016, pg. 1). What’s more is that, in the more recent Nairobi Ministerial conference, domestic agricultural subsidies were not dealt with and “remain high and are proliferating,” (Lester 2016, pg. 1). In summary, while some progress on opening agricultural trade for the benefit of developing countries has been made, the issue remains largely unresolved due to the developed countries’ refusal to budge on the issue of domestic subsidies and trade-distorting protections.

Another major area of concern for the Doha Round was the issue of increased Trade Liberalization and Trade Facilitation across the board, specifically for developing countries. Though the Doha Round, as mentioned above, failed to properly address some of the major issues on its agenda, the development round did manage to produce some noteworthy, albeit modest, progress in the realm of trade facilitation with the ratification of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (referred to as the TFA). The TFA was ratified in December 2013 at the Bali Ministerial Conference and is the “first new WTO multilateral agreement” since the actual creation of the WTO at the end of the Uruguay Round (Eliason 2015, pg. 643). The purpose of the TFA, and Trade Facilitation in general, is to ensure the smooth, frictionless entry of goods into a country with as minimal costs and barriers to entry as possible. The TFA itself could reduce the costs of cross-border trading by $1 trillion through its capacity to “improve transparency…[reduce] institutional limitations, and [improve] access to information,” (Eliason 2015, pg. 644-645). With regards to efforts in promoting trade liberalization, the Doha Round produced the second iteration of the Information Technology Agreement. The (second) Information Technology Agreement is a trade agreement amongst 53 WTO member countries at the 2015 Nairobi Ministerial Conference aimed at significantly lowering tariffs on information technology products (Lester 2016, pg. 2)

The WTO Today

There is, of course, the unresolved matter of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (referred to as TRIPS) and the difficulties that developing countries encountered in implementing the measures reached in this agreement. The TRIPS agreement was ratified and implemented in 1995 along with the establishment of the WTO itself and is one of the most “most comprehensive multilateral agreements on intellectual property,” (Hartman 2013, pg. 419). While this is certainly an impressive enough accomplishment for international trade, the problem is that developing countries had no meaningful or effective ways to implement some of the measures of the TRIPS agreement. The inability of developing countries to fully implement the TRIPS agreement is reflective of the broader “challenges facing developing countries in undertaking policy and regulatory reforms,” (Verbiest et al. 2002, pg. 2). In fact, estimates illustrate that, if developing countries were to adjust and implement the TRIPS agreement, they would be paying “$60 billion per year in royalties,” (Verbiest et al. 2002, pg. 2). The inability of developing countries to implement the TRIPS agreement was particularly detrimental to public health and the ability for these countries to address epidemics within their borders. The Doha Round came close to addressing this issue in approving a 2005 WTO Declaration that would create a solution for developing countries and the issue of compulsory licensing, but this attempt went nowhere (Hartman 2013, pg. 419-420). Other roadblocks for the Doha Negotiations came in the form of environmental trade. Throughout the Doha Round, the goal of getting rid of tariffs on environmental goods has been blocked due to “increased national trade restrictions” in response to the 2008 Financial Crisis (Hartman 2013, pg. 420-421). Yet another roadblock the Doha Round encountered during an already long and arduous series of fruitless negotiations. Despite the number of issues, the Doha Round set out to tackle, very little was accomplished and developing member countries gained virtually nothing.

The Doha Round of negotiations encountered numerous obstacles in attempting to achieve many of the issues on its agenda, either due to external factors or internal, structural faults latent within the WTO. Developing nations did not receive any substantial benefits from these negotiations in the way of increased market access for agricultural products or increased support for implementation of the objectives outlined in the TRIPS agreement. More importantly, the outcomes (or lack thereof) of the Doha Round may have broader implications for the WTO, questioning it as an efficacious institution in its attempts to promote frictionless international trade.

Conclusion

In discussions about international trade, both the General Agreements on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) have played important roles. The post-World War II economic and political environment set the stage for the need for a rules-based system for international trade and the need for an institution to facilitate the flow of trade. Taken together, both GATT and the WTO have produced some of the most all-encompassing, internationally recognized, and politically important trade agreements in modern history whose outcomes have wide-reaching economic and political implications. From its inception in 1947 to 1995, GATT has undergone eight complete rounds of trade negotiations among increasing numbers of members with each round ultimately serving the goal of reducing international trade barriers and promoting more open and more transparent systems for global trade among countries. Among GATT’s many achievements in promoting international trade, the eighth and final round of trade negotiations – known as the Uruguay Round – is perhaps the institution’s crowning achievement. As discussed previously, the Uruguay Round was one of the most exhaustive sets of negotiations and trade agreements (ranging from agriculture to sanitary standards to intellectual property) ever constructed in modern history and, ultimately, epitomized the GATT’s mission statement. Once more, it was this round of negotiations that created GATT’s successor: the WTO.

The WTO’s purpose was, like GATT, to reduce global trade barriers and facilitate freer trade between nations. The WTO now includes three times as many members as GATT and takes into consideration the interests of many more nations. But while the WTO might be GATT’s successor, has it truly succeeded where GATT has otherwise stumbled? The outcomes, or lack thereof, of the latest round of trade negotiations under the WTO (the Doha Round) point to a more pessimistic answer. While the Doha Round was set to address issues that were important to developing nations, issues that were not properly addressed in the Uruguay Round, the negotiations met various internal and external roadblocks and failed to achieve anything meaningful. As mentioned before, issues on market access for agricultural goods from developing nations, reductions in trade-distorting domestic, support for agricultural goods in developed nations, and other such problems persisted to some extent, even after many negotiations over an extended period. So, where does this leave the WTO? Is the Doha Round a unique case? Can the WTO move on and continue to push towards its primary objective in the way its predecessor had done? Or are the difficulties encountered in the Doha Round reflective of a larger, internal problem of the WTO? Should developing nations, whose interests have either been neglected, denied, or pushed back, seek out alternative means (i.e. regional trade agreements) of reducing trade barriers and realizing their economic pursuits? Or is the WTO simply no longer relevant in today’s international stage? While these questions may not have an immediate answer, it is important to consider as the WTO pushes on into a future of economic uncertainty and international instability. For the goals of the WTO to be realized, the institution itself, as well as its successes and failures, must constantly be reevaluated.

Work Cited

Aaronson, Susan Ariel. Taking Trade to the Streets : The Lost History of Public Efforts to Shape Globalization, University of Michigan Press, 2001. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utd/detail.action?docID=3414968.

Anderson, K.. World Trade Organization. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/topic/World-Trade-Organization

Anderson, K. . Peculiarities of retaliation in WTO dispute settlement, 2002. World Trade Review, 1(2), 123-134. doi:10.1017/S1474745602001118

Barton, John H., et al. The Evolution of the Trade Regime : Politics, Law, and Economics of the GATT and the WTO, Princeton University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utd/detail.action?docID=664555.

Dijk, Meine Pieter van., and S. Sideri. Multilateralism Versus Regionalism : Trade Issues after the Uruguay Round. Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 1996. Print.

ELIASON, ANTONIA. “The Trade Facilitation Agreement: A New Hope for the World Trade Organization.” World trade review 14.4 (2015): 643–670. Web.

Fefer, Rachel F. “The World Trade Organization – Congress.” Congressional Research Service, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10002. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10002

Genève internationale 15 April 1994 – Signature of the Final Act of the Uruguay Round at Marrakesh | https://www.geneve-int.ch/node/3976

Georgetown Guides. International Trade Law Research Guide: WTO & Gatt Dispute Settlement, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=363556&p=3915307

Hartman, Stephen W. “The WTO, the Doha Round Impasse, PTAs, and FTAs/RTAs.” The International trade journal 27.5 (2013): 411–430. Web.

Heakal, R. What is the World Trade Organization? Investopedia, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/investing/what-is-the-world-trade-organization/

Hoekman, B. M. World Trade Organization (W): Law, economics, and politics. Routledge, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2022

Laborde, David, and Will Martin. “Agricultural Trade: What Matters in the Doha Round?” Annual review of resource economics 4.1(2012):265–C3.Web.https://www-annualreviewsorg.libproxy.utdallas.edu/doi/pdf/10.1146%2Fannurev-resource-110811-114449

Lester, Simon. “Is the Doha Round Over? The WTO’s Negotiating Agenda for 2016 and Beyond.” Cato.org, Cato Institute, 11 Feb. 2016, https://www.cato.org/free-trade-bulletin/doha-roundover-wtos-negotiating-agenda-2016-beyond

Mavroidis, Petros C.. The Regulation of International Trade, Volume 2 : The WTO Agreements on Trade in Goods, MIT Press, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utd/detail.action?docID=4527740.

Ossa, R. . A “New Trade” Theory of GATT/WTO Negotiations. Journal of Political Economy, 119(1), 122–152. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1086/659371

Sander, Harald., and Andr’s. Inotai. World Trade after the Uruguay Round : Prospects and Policy Options for the Twenty-First Century. London ;: Routledge, 1996. Web.

Saylor Academy. (n.d.). Introductory trade issues: History, institutions, and legal framework: The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://learn.saylor.org/mod/book/view.php?id=52385&chapterid=33549

Subedi, Surya P. “The Road From Doha: The Issues for the Development Round of the Wto and the Future of International Trade.” International and Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 2, 2003, pp. 425–446., doi:10.1093/iclq/52.2.425. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-and-comparative-lawquarterly/article/road-from-doha-the-issues-for-the-development-round-of-the-wto-and-thefuture-of-international-trade/E275B587814502B003F4189D8F783A26

Verbiest, Jean-Pierre; Liang, Jeffrey; Sumulong, Lea. 2002. The Doha Round: A Development Perspective. © Asian Development Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/11540/2160. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://think-asia.org/handle/11540/2160 • WTO. (n.d.). Understanding the WTO – principles of the trading system. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact2_e.htm

WTO. (n.d.). Understanding the WTO – a unique contribution. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/disp1_e.htm • WTO. (2022, April 21). UNDERSTANDING THE WTO: BASICS. Retrieved from The Uruguay Round: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact5_e.htm

WTO. (n.d.). Understanding the WTO – principles of the trading system. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact2_e.htm

WTO. (n.d.). Understanding the WTO – a unique contribution. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/disp1_e.htm • WTO. (2022, April 21). UNDERSTANDING THE WTO: BASICS. Retrieved from The Uruguay Round: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact5_e.htm

“WTO | The Doha Round.” WTO, World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dda_e/dda_e.htm.

World Trade Organization. (n.d) The WTO agreements Serie 2S Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/agrmntseries2_gatt_e.pdf